Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

The sun shone down on the bow of the Ann Brita as I stood on its green metal deck, reaching out to take hold of the boat’s grenade harpoon. Its stripes of green, black, and gold paint were still fresh. I tensed under the weapon’s weight as I slowly moved it back and forth in my hand like a whaler might, just before moving in for a kill.

Gazing out at the Norwegian harbor of Reine, I lined up my eyes with a target that didn’t exist: a minke whale, slyly cresting the surface with its sleek, dark body, casting a powerful whoosh of breath into the air. The next steps were beyond me.

All around, staggering peaks plunged into azure waters. By my side was a whaler whose grandfather first fished from this boat. I can still smell the dry cod that permeated the air. I can also feel my happiness, and the paradox of that emotion.

So much had transpired to get me there.

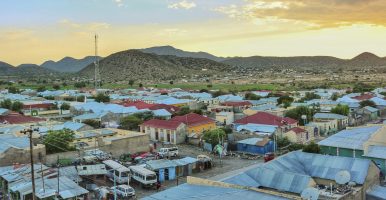

The tranquil Norwegian fishing village of Reine hugs the shores of Moskenesøya island, part of the wild Lofoten archipelago above the Arctic Circle. Photo: Gemina Garland-Lewis.

~~

Save the Whales. As a child in New Mexico in the 1980s who dreamed of becoming a marine biologist, those three words were more than an environmental movement — they formed the foundation of my worldview.

At the age of 11, I walked into a restaurant and laid eyes on a tank of live shrimp. In that moment, I decided that if I wasn’t comfortable taking an animal’s life, I shouldn’t eat it. I haven’t wavered on my choice since. Around that same time, I got my first taste of activism signing a petition to halt a salt mine development in the gray whale birthing lagoons of Baja California Sur.

It was easy to paint a simple picture: Hunting whales was bad; saving them was good.

But in college, a maritime studies course shed light on parts of the whaling story I hadn’t been told. After graduation, my curiosity about the nuances of the human-whale relationship landed me a yearlong fellowship to seven countries.

And so, in the summer of 2008, I set off in search of cultural understanding.

On a remote beach in Argentine Patagonia, southern right whales and their calves swam so close to shore it seemed I could almost reach out and touch them as they spun their square flippers above the water.

A whale-watching boat follows a southern right whale off the coast of Puerto Pirámides in Argentine Patagonia. Hunted during the industrial whaling era, this now protected species of baleen whale gathers in these southern waters to breed. Photo: Gemina Garland-Lewis.

In the Azores, speaking with old whalers, I watched as their eyes drifted to sea, burning with desire to be in their seven-man canoa, lance in hand, chasing a sperm whale.

Former whalers hang out in front of their old whaleboat house in Ribeiras, Ilha do Pico, in the Azores. Refusing to adopt modern technology, Azorean whalers hunted sperm whales using hand harpoons and lances aboard seven-man wooden boats until 1987, when the last whale here was killed. Photo: Gemina Garland-Lewis.

I sipped coconut water on a small island in the Ha‘apai Group in Tonga with a one-armed man, Kalafi, who told me how, as a boy, he’d always tried to stand on the backs of whales — but that they were too slippery.

And in Japan and Norway, the only two countries I visited that year with active whaling industries, I was forced to reconsider my preconceptions — and the cultural baggage I had brought with me.

~~

Across a wide field of yellowing grass lined with palm trees, the Taiji whale museum rose up against a forested hill. Massive paintings adorned the building’s face and side, depicting both traditional and modern visions of North Pacific right whales — now the world’s most endangered whale species. Artistic renderings like these had guided me here like a trail of crumbs.

When I embarked on my fellowship, I knew Japan would be my biggest challenge. I was scared of what I might encounter in a place with a relationship to whaling unlike anything I knew as an American.

It was easy to paint a simple picture: Hunting whales was bad; saving them was good.

Taiji is the presumed point of origin for organized whaling in Japan, dating to the 1600s. In just a few months, a documentary called The Cove would make waves globally for excoriating this small town’s dolphin-hunting practices. And yet, from the moment I stepped off the train and came face to face with whale murals dancing along the platform, I had been struck by Taiji’s reverence for creatures of the sea — with many of the same hallmarks of whale-watching towns I had visited elsewhere.

I made my way to the museum slowly, passing fountains of whale tails. Inscribed in small sidewalk tiles were the Japanese characters for dozens of cetacean species. I eagerly copied them in my notebook.

For photographer Garland-Lewis, this whale-tail fountain in the whaling town of Taiji, Japan, conjured the memory of a similar sculpture in Hermanus, South Africa, a favorite destination of whale watchers. Though the two places diverge in their approach to whales, their visual identities converge. Photo: Gemina Garland-Lewis.

The museum put the deep history of Japanese whaling on display. Most historians agree that some form of whaling has existed in the Japanese archipelago since prehistoric times. Dioramas showed the evolution from early hunts off the coast with hand harpoons and wooden canoes, to the massive factory ships of the mid-20th century, which harvested whales primarily for oil rather than meat, to the smaller vessels used today.

Outside, in a small natural cove, pilot whales and Risso’s dolphins performed tricks for the amusement of a gathered crowd. Farther out, a lone orca leapt out of the water over a lofted pole, then jumped straight up in the air to nose a buoy held high by a trainer on a dock.

Back inside, I turned the corner to the gift shop and spotted something that stopped me in my tracks. For sale, among whale-shaped cookies and trinkets, were boxes and cans of whale meat.

Here, it seemed, appreciating animals took more forms than my mind could easily reconcile. Dolphins and whales were tied up in cultural identity and history, but they also provided a source of entertainment and food. What felt to me like opposing poles were parts of a whole. The realization left me reeling.

A stylized drawing of a whale caught the photographer’s eye while walking through Kyoto, Japan. Photo: Gemina Garland-Lewis.

For most of Japan’s history, whale meat was only eaten in certain areas and communities, such as Taiji. World War II changed that.

During the war’s final stages, much of the nation’s cities and industries were decimated — whaling included. Following the war, as the Japanese people faced dire food shortages, the American occupation authority saw an opportunity to promote a cheap source of protein.

In 1946, on the orders of General Douglas MacArthur, two military tankers became whale ships, Japanese whaling zones were extended, and — amidst much controversy — Japanese whaling in Antarctica resumed after a wartime hiatus. From there, whale distribution reached new levels in Japan as it made its way to school lunchrooms around the country. It was most often served as kujira no tatsuta-age — deep-fried whale meat, as part of a Western-style nutrition campaign to introduce more fat and meat into the Japanese diet.

For the first time in Japan, whale became a national dish.

~~

One morning in Tokyo, I rose early to inspect each aisle of the massive Tsukiji fish market. In my hand I clutched my passport to this world — my notebook, with a drawing of a whale I used to ask simple questions and a list of the Japanese names for different species that I had carefully copied from those sidewalk tiles in Taiji.

Fish carts flew by, forcing me to stay alert, as my eyes scanned hundreds of vendors for the deep red meat of a mammal or the grayish white of blubber. Rarely did I find what I was looking for.

In 2009, scanning for whale vendors among the aisles of Tokyo’s massive Tsukiji fish market proved to be an exercise in persistence. After 83 years of business at this site, the famed wholesale market relocated to a more spacious setting in 2018. Photo: Gemina Garland-Lewis.

Much of my time in Japan found me wandering from one market to the next, desperate for clues. When I did find whale, I’d linger near the restaurant or vendor to watch. Who came in? How old did they look? Did they buy anything? Did they turn away?

By the time I arrived here in 2009, whale meat was no longer a lunchroom staple. In many parts of the country it was scarce. Hoping for insight, I had emailed a range of representatives of whaling and environmental organizations. Almost no one responded. Talking about whaling with an American, it seemed, was taboo.

In Nagasaki, the prefecture with the country’s highest whale meat consumption per capita, I enlisted Nana, a young woman who ran the hostel where I was staying, to translate. One older woman, with perfectly coiffed hair and bright red lipstick, told us she had run her whale meat shop for over 60 years. She ate whale daily, avowing that it helped with strength, beauty, complexion, and stomach problems. Among her selection was fin whale, an endangered species.

“Every country has their own culture, and other countries should respect that,” she said. I couldn’t argue.

Soon, though, our conversation turned to the fact that Australians — who, like Americans, are outspoken critics of Japanese whaling — consume kangaroos. “We might think ‘poor kangaroos,’” she said, “but we don’t get mad at them about it.”

I’ve always been dubious of the lines that humans draw around which animals are okay to eat. But to compare whale consumption to that of the kangaroo — an animal more populous than the humans of its country — tapped into an anger deep inside me, pushing the limits of my research neutrality.

In Tokyo’s Tsukiji fish market, slices of whale blubber sit on display alongside frozen cuts of red meat. Photo: Gemina Garland-Lewis.

At the same time that the United States occupation authority was encouraging a resurgence of the whaling industry in Japan, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) formed.

Centuries of commercial whaling had severely depleted the populations of many whale species, especially during industrial whaling in the Southern Ocean. All told, 20th-century whalers took nearly three million whales from the world’s oceans. The IWC missive was to manage whale stocks for “the orderly development of the whaling industry” — to hunt responsibly.

But just over three decades later, a shift was underway. Industries historically in need of whale products found cheaper and more accessible alternatives, and the cultural mindset of many former whaling nations pivoted away from hunting.

In 1982, the IWC voted to pass a moratorium on commercial whaling, with the intention of helping populations recover and to better assess whale stocks. It wasn’t a hard stop, though. When it went into effect in 1986, the hiatus was only intended to be temporary, with a new review by 1990.

~~

After Japan, I flew to Oslo, Norway, where I headed from the airport to the apartment of my Couchsurfing host, Anette. A woman in her 20s with a bright smile and colorful dreadlocks, she wanted to throw me a welcome party in the backyard of her apartment building. Together, we walked to a corner store to get food for the barbecue.

And there, in a freezer island, was the dark red of whale flesh. By now, the sight had lost its sting. But what struck me was how challenging it had been to find in Japan, how many markets I’d scoured. Here in Norway, it had shown up on my first night, without me even trying. I knew, without asking or consulting my notebook, what species it was. Although responsible for some of the worst devastation of whale stocks during industrial whaling, today the Scandinavian country hunts only the non-threatened minke whale. Once considered too small and fast to be profitable, the species only became a target upon the depletion of most other whale populations.

Back at the party, I was transported to a world where people had names like Rudolf and Frode and conversation flowed as freely as booze. It was a lovely late-spring evening, and the strums of an acoustic guitar filled the air.

As I got to know people that night — some who remain friends to this day — my questions came tumbling out. After nearly two months in Japan without many meaningful conversations, I couldn’t contain my curiosity. How long ago did you last eat whale? What do you think about your country whaling?

Almost everyone in this 20something crowd had eaten it recently. Nobody saw a problem with whaling, as long as it was done sustainably. Though I didn’t ask, some of my new friends added that whale tasted great.

~~

When the IWC moratorium passed, three countries maintained formal objections — Japan, Norway, and the USSR. The IWC is not a regulatory authority and objecting within 90 days of the vote left those countries unbound by the decision.

In 1987, though, Japan revoked its objection to the moratorium after the U.S. threatened fishing sanctions. At that point, Japan entered a new phase of whaling by special permit, both in their own waters and in the Antarctic — leaving them as the sole country still taking whales from the Southern Ocean.

These permits allow the catching of whales for scientific research. Anti-whaling nations often describe this as a loophole and accuse Japan of carrying out commercial hunts disguised as science. The IWC stipulates that whales taken for scientific research should “so far as practicable be processed” to prevent waste.

Even so, as whale meat consumption has decreased and supply tops demand, meat from these whales often piles up, frozen in storehouses.

~~

One afternoon, I sipped a cup of tea in the small Norwegian fishing community of Henningsvær, a scattering of wharves and docks spread across rocky islands. I sat across the kitchen table from Heike Vester, a biologist who runs a small nonprofit researching cetacean acoustics. She told stories of her work and her encounters on the seas with whalers. Though anti-whaling herself, she questioned the militant tactics employed by some environmental groups.

Just over a month before my arrival, Vester told me, an anti-whaling group called Agenda 21 had sunk a local boat, the Skarbakk, here in Henningsvær. Emotions were high. The act of violence, she said, had created a deep tension that stymied any hope of ending whaling.

“If you want to make change,” she said, “you need to go to the government — they’re the ones who set the quotas. Don’t make it personal.”

Although responsible for some of the worst devastation of whale stocks during industrial whaling, today the Scandinavian country hunts only the non-threatened minke whale. Once considered too small and fast to be profitable, the species only became a target upon the depletion of most other whale populations.

From the Norwegian government’s perspective, the sustainability of the harvest is what matters. The annual quota is currently set at 1,278 whales, but in recent years, whalers have taken less than half that number — representing less than 0.5% of the estimated local minke whale population. Of course, for many who oppose whaling, the sustainability question is moot.

Vester shared dispatches from her colleagues in the IWC, who talked of near-concessions made by Japanese representatives that had failed after protestors doused them in red paint and called them murderers.

Such attacks on whaling are often interpreted not as pro-whales but as anti-Japanese. The Japanese call it kujira nashonarizumu — whale nationalism. In 2011, an Associated Press opinion poll found a slim majority said they favored commercial whaling and the sale of whale meat. Yet only 12% responded that they were very or extremely interested in eating whale, and 66% reported no interest at all. Some have coined this apparent contradiction “anti-anti-whaling,” meaning that Japan is less in favor of whaling than it is in opposition to criticism from the West, especially the United States.

One big reason: America remains one of the few nations in the world with a whaling permit. The U.S. allows for aboriginal whaling, primarily of endangered bowhead whales by Indigenous communities in Alaska. Whether this subsistence catch is more acceptable than a bigger harvest of non-endangered species is a matter of heated debate.

Whaling, it was becoming clear, was a geopolitical issue. Often it wasn’t about whales at all.

~~

These revelations weighed on my mind that June day when I felt the heft of the harpoon grenade while standing at the bow of a whaling boat docked in Norway’s spectacular Lofoten archipelago. The brightly painted grenade, complete with fresh serial numbers used to track each whale hunt, sparkled in the midday light.

An hour earlier, I had veered off the main road along a dirt driveway that led to a dock where a ship was tied off. A thick black band circled the crow’s nest to signal its use as a whaling boat — most of the year, the band isn’t there, and this would be an ordinary fishing vessel.

In Japan, it would have been nearly impossible for me to approach an operational whaling ship, but by this point, I understood things were different here.

I found some men working on the boat and introduced myself. A young man with short blonde stubble and a blue Von Dutch trucker cap, Bjørnar Olsen, offered to show me his grandfather’s boat.

Norwegian whaler Bjørnar Olsen continues his family’s decades-old tradition of whaling aboard his grandfather’s boat. Photo: Gemina Garland-Lewis.

The Ann Brita had just come back from two weeks of whaling up north in Svalbard, a trip Bjørnar had worked with his brother, father, and two neighbors. His grandfather was still working after more than 50 seasons, he told me. Plastered with photos like a scrapbook, a framed poster board hung in the interior cabin as a chronicle of the family’s many outings on their ship.

Bjørnar admitted that his family continued whaling out of tradition more than anything else. If they ever stopped turning a profit, he said, they’d stop. He opened the hatches to where meat is stored, the ice in the holds still stained red with blood. Large double-pronged hooks, used to move the meat, hung nearby.

As we walked the decks of the ship, I asked him why he thought countries like the U.S. and Australia scrutinize Japanese whaling while largely ignoring it in Norway. He insisted that this difference was rooted in prejudice against the Japanese.

Olsen shows the serial number added to grenades — part of the government’s system of checks and balances designed to prevent illegal whaling. Photo: Gemina Garland-Lewis.

I climbed up to the crow’s nest and surveyed my surroundings, imagining the heavy movement I would feel on open water. As a sailor, standing at this lookout on a ship always brings me joy. But that day the thrill came from a different sort of vantage — seeing this place through the eyes of someone I may have never given the time of day, were it not for what had changed in me.

The crow’s nest overlooks the bow of the Ann Brita and the grenade harpoon mounted to the deck. During a hunt, whalers climb up here to scan the sea for a flash of a tail or spout or even a vapor plume from the creature’s breath. Photo: Gemina Garland-Lewis.

~~

Today, nearly 30 years after the IWC passed what was intended as a short-term moratorium, the ban persists. In 2019, after withdrawing from the IWC, Japan resumed commercially hunting minke whales in its own waters.

According to Dr. Fynn Holm, a research fellow and lecturer in Social Sciences of Japan at the University of Zurich, this move was primarily political. The Japanese government could withdraw, believing the action was unlikely to provoke sanctions from the Trump administration, while also saving face. The nation could end “financially disastrous” scientific missions in the Antarctic without seeming to have bowed to pressure from international NGOs.

Whaling, it was becoming clear, was a geopolitical issue. Often it wasn’t about whales at all.

What The Washington Post called an “act of defiance” — outlining one Japanese mayor’s vow to add whale meat to 100,000 school lunches a year — has actually resulted in a decreased hunt, almost halving Japan’s whale kill in the first season that commercial whaling resumed. Japan calculates its annual quota — 383 whales for 2021 — using the IWC’s method for determining what would make a sustainable catch limit.

Meanwhile, whaling boats such as the Ann Brita continue their annual commercial hunts for minke whales along the coast of Norway. Catch limits there have steadily risen over the past two decades. Even so, the appetite for whale meat may be diminishing compared to what I encountered at that backyard barbecue a dozen years ago: A recent survey found only 4% of respondents regularly consume minke. Even so, in 2020, the demand for whale in Norway surpassed its supply for the first time in years, as more Norwegians vacationed in the North due to travel restrictions. Whaling is unlikely to stop in Norway anytime soon.

Docked in the Reine harbor, the Ann Brita awaits its next sea voyage. A black band on the crow’s nest signals that the fishing boat is currently in use to hunt whales. Photo: Gemina Garland-Lewis.

These days, I live in San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, an hour from the lagoon once slated for a salt mine development that I had protested as a child. In this world where desert and sea collide, I anticipate the winter arrival of Pacific gray whales, waiting to feel the sound of their sharp exhale reverberating through my chest, or perhaps even stare into the eyes of curious moms and calves that approach our small boats.

Like other wild animals, this species is struggling to adapt to climate change, leaving them stranded and starving along North America’s West coast. But this “unusual mortality event,” as the die-off is called in scientific terms, isn’t the only threat facing whales that has nothing to do with harpoons. The IWC estimates that an incredible 300,000 whales and dolphins die each year after getting caught in fishing gear — that’s 20,000 more fatalities than in industrial whaling’s most intense five-year period in the Southern Hemisphere following World War II.

This figure likely underestimates the actual toll.

~~

Back in 2009, I made my way to yet another small fishing town in Japan, Kayoi on Omijima Island, where a small community lies at the end of a road, among steep cliffs and sea caves carved by the open waters of the Sea of Japan. I arrived during a downpour and walked along cobblestone streets slick and shining from the rain, following signs with the only three hiragana letters I had come to recognize on sight: くじら — whale.

Raindrops streamed through my hair, onto my face, and under my collar. Making my way down the empty street, I side-stepped puddles and maintenance hole covers painted with cartoonish, bright blue whales.

The Kogan-ji temple in this town maintains a funeral registry for whales killed here in centuries past. Buddhist nuns offer daily prayers for those lives lost.

Signs marked kujira — whale — lead the way through the streets of Kayoi to the steps of a graveyard for whale fetuses. Photo: Gemina Garland-Lewis.

Finally, in a back alley and up some steps, I found what I had come all this way to see: An obelisk, not much bigger than me, rose in the middle of a small rock garden. Built in 1692, the stone monument marked the burial site of 70 unborn whale calves, taken with their mothers during the peak of Japanese whaling on this coast.

“Our purpose isn’t to catch fetuses,” read a plaque. “We would rather have left them in the sea, but we can’t return them to the sea. They won’t survive. Therefore, we made this tomb because we feel sorry for them and we want them to rest in peace.”

Taking off my shoes, I stepped into the adjacent small shrine, my socks drenched, and noticed a donation box for Kannon, goddess of mercy. I dropped a ¥10 coin into the slot.

I paused to let the weight of what I had encountered so far wash over me — the gratitude and guilt saturating this community, the multifaceted traditions and prejudices that imbue each of our narratives.

When I set out, I prepared myself to offer mercy, to draw from deep within as I confronted perspectives that seemed antithetical to my own. Instead, I learned that true mercy lives in conversations and cooperation reaching beyond those divides. That’s where hope is found, too.

Gemina Garland-Lewis

Gemina Garland-Lewis is a Pacific Northwest and Baja CA Sur-based photographer, scientist, and explorer whose work explores human-animal-environment relationships around the globe. She is a lover of the outdoors, curiosity, and cheese.