Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

This story has been published in the 2024 Pathfinder Issue of Hidden Compass. While every story has a single byline, storyteller proceeds from patronage campaigns in this issue will go collectively to Team Beyond the False Summit on top of their article pay.

In a Hidden Compass first, we’re running a three-part series of articles by a single author: expedition leader Lance Garland. This is Part Three of the series. The expedition begins with Part One, “Climbing the Unforeseen,” and continues in Part Two, “Escaping the Trap.”

The alpine air is silent above the Mer de Glace glacier, no rustling of wind nor human, save the four of us. We gather on an outside ledge of the Envers hut just after 3:00 a.m., and the dark ring of the Mont Blanc massif surrounds us like an impregnable fortress. Snow atop the Trélaporte glacier glows from a full moon as we make our first crunchy steps across the ice with crampons affixed to our boots. For the first time on this expedition, I feel completely at home.

As my headlamp illuminates my next steps, memories of Pacific Northwest ascents on glaciated peaks flood my brain. After a short traverse of the glacier, we search for a way to get off it, and onto the face of Aiguille du Grépon, an 11,423-foot behemoth of granite.

With the world illuminated by moonlight and their way illuminated by headlamps, the team begins their ascent of Aiguille du Grépon, traversing an icy glacier. Photo: Ben Tibbetts.

We’re here because of Geoffrey Winthrop Young. In 1911, he was part of the team that made the first ascent of the east face. They called it the Mer de Glace route, and our team is attempting it one hundred and thirteen years later. Young, along with Humphrey Owen Jones and Ralph Todhunter, hired Henri Brocherel and Josef Knubel as guides to attempt a climb that had the region’s hardest known rock-climbing pitch at the time. Only Knubel would be capable of leading the final pitch, a jutting crack that requires skill and confidence — a crack that is now named after him. I wonder how I’ll do at that crux. It will be the hardest pitch of my climbing life.

The gap between the glacier and the mountain is growing massive, and thankfully, we find a sketchy finger to jump from. As the summer continues to melt the glacier, this opportunity won’t be here for long.

“We might be one of the last teams this year to climb this route,” Ben says. He may be right: We’ll only see one other team anywhere near this mountain today, and we’ll never cross paths.

Valentine is the only member of our crew who has climbed this mountain, and she did so six years ago with someone else leading the way. Initially, we lean on her to route-find, but all have the guidebook routes on our phones.

I can almost see Geoffrey and George climbing together … forging a bond that lasted their lifetimes and beyond, calling me here.

Across the moonlit Mer de Glace stands Aiguille Verte, a 13,524-foot jagged rock face that resembles the other razor-like mountains in this range. During their summer travels, Young snapped a famous picture of George Mallory standing on Verte’s Moine Ridge, gazing over toward the ridge we stand on now. In my pack, I have a physical print of that picture and a portrait of Young smoking a pipe as well — tokens to feel close to them on this climb. I’ve become fascinated by this man with whom Mallory had spent those summers across the Alps, Geoffrey Winthrop Young.

Valentine assesses the leap from glacier to rock. Photo: Ben Tibbetts.

~~

Born in London, England, in 1876, Young built a distinguished life as an educator in England’s most prestigious schools and raised two children with his wife, Eleanor Slingsby. He also became an elite mountaineer and authored books of poetry, outdoor education guides, and climbing memoirs. When he died in 1958 at the age of 81, he was a veritable icon of alpinism. Although he was celebrated during his life, so much of who he was remained hidden until after his death.

Last autumn, I found a rare book sold by a used bookstore in England, Alan Hankinson’s now out-of-print biography Geoffrey Winthrop Young: Poet, Mountaineer, Educator. In it, Hankinson claims that Young was fired from his job as a teacher at Eton in 1905 because of his sexual identity. The only written explanation of the situation seems to be a record from Eton that reads: “following his departure in exceptional circumstance.” But Hankinson expounds, “There is no definitive evidence then, but there can [be] little doubt … that Geoffrey was dismissed because he had been found guilty of some homosexual activity.”

~~

As we climb, Young’s past brings flashes of my own. I, too, have lost a job due to homosexual activity. A hundred years after Young was sacked from Eton, in 2005, I was in the long, slow process of being separated from the U.S. Navy under the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy. The glaring eyes of that jury as I stood as a witness in a court-martial is seared into my memory. My testimony would sever me from further service. Even now, I think of all the places where it’s dangerous to be gay. For all the change the world experienced during the century that separates us, I’ve walked a path similar to Young.

Yet he soldiered on. He climbed extensively and found work as His Majesty’s Inspector for schools across England. The steady work allotted him time to write and climb. During his twenties, Young explored his sexuality in what Hankinson calls “riotous weekends in Paris and Berlin.”

These forays into a world where he could experiment produced strong emotions within him. Young wrote in his journal, “I am almost afraid … what a crash it would mean if my strange nature with its … natural audacities, and complete freedom from old prejudices … and what is called “morality” ever came out — as it may any day — in one of the innumerable corners where I have eddied up and down disregarding the so-called ‘risk.’”

Hankinson elaborates, “Many journal entries at this period make it clear that his excursions into the homosexual underworld were the cause of much agonizing introspection … Blackmail was a serious possibility, and public revelation was another, and there can be no doubt that Geoffrey was concerned to keep the truth from his parents, his employers and colleagues.”

Young’s fears came to a threatening crescendo in early 1914. Just eight years after losing his job at Eton, he was forced to resign from his job as His Majesty’s Inspector due to his double life being found out. Nearing forty years old, Young understood that if he continued to live as a gay man, he would likely end up with nothing. Later that year, World War I erupted across Europe, changing Young’s life forever.

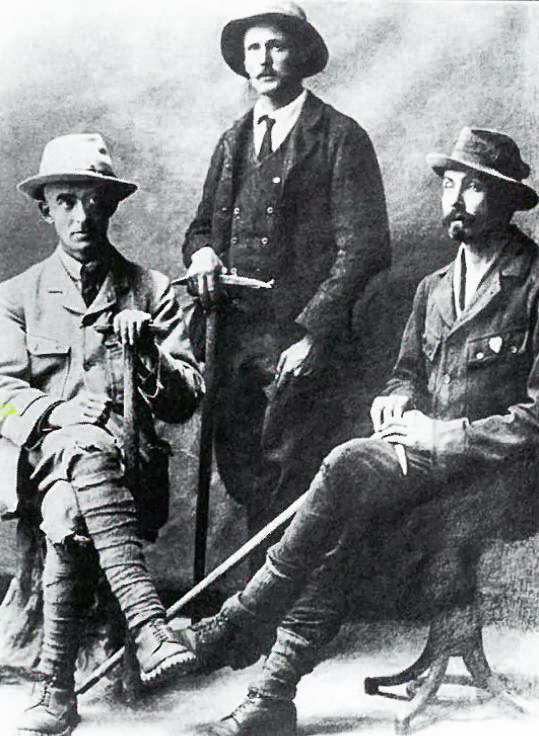

Humphrey Owen Jones (left), Josef Knubel (center), and Geoffrey Winthrop Young (right) sit for a portrait in Chamonix, France, in 1911. The three made the first ascent of the Aiguille du Grépon via the Mer de Glace route. Young is also one of the historical figures at the center of this year’s Pathfinder expedition. Photo: Unknown.

~~

Before we’re halfway up the mountain, I become extremely nauseated. Is it the altitude? All my endurance training has taught me to acknowledge discomfort and adjust accordingly. In an effort to self-regulate, I slow my pace and focus on my breathing. It helps.

Most of the time, we’re alone, connected to one end of a rope with a lot of space in between. I see Jordan the most, and he’s at ease, climbing this behemoth of granite like a casual day in the park. Only occasionally do all four members of our team gather, and when we do, Valentine speaks mostly to Ben in French. She’s a stoic figure, stature straight as a salute, laser-focused on the task, and uninterested in small talk. At one point when we see each other, Ben checks in, seemingly worried.

“How close to being worked are you?” he asks.

“Oh, I’m about halfway there.”

“It’s a good thing you’re in such great shape.”

To me, his check-in is a sign of a healthy team, and I am grateful for it.

The dark ring of the Mont Blanc massif surrounds us like an impregnable fortress. Snow atop the Trélaporte glacier glows from a full moon as we make our first crunchy steps across the ice.

While I have a lot of experience scrambling, it’s my first time simul-climbing, where both climbers on a rope move at the same time. The lead climber places the protection as the follower removes it on their way up, a style where neither climber stops to belay the other.

My partner is Jordan, and he’s known for his meticulous organization. When we meet on stable ledges, I hand his gear back in disarray. Gumby again. Good thing I have a fondness for that Claymation character from my childhood. I can’t meet Jordan’s standards no matter how I try. I thank him regularly for forgiving my messiness. He responds, “It’s a learning process.”

Then I leave behind a piece of protection — a spring-loaded camming device — a mortal sin of traditional climbing. Jordan is a gentleman about it, but it’s clear that I’m not impressing anyone out here. Ben calls it a “gift to the gods,” and the crew will make sure I get every other piece of gear from now on. I respond, “I earned that.”

I continue to dampen my nausea by eating an apple and drinking more water. I’m hungry, but it’s better than being nauseated. I’ve found a good balance. As we wait for Valentine and Ben to find the route above, Jordan plays punk-rock music from his phone, and we sing along, perched on a ledge in the Mont Blanc massif, bonding from our shared love of irreverent music.

Before the climb, Ben did some research of his own, digging into the life of his fellow countryman, Young. He found a trip report from Humphrey Jones, a member of the original climb, who wrote, “The climbing was always difficult … verging on the impossible, undoubtedly superb. Chimney, slab and crack, always steep, sometimes even overhanging … in rapid and bewildering succession.” He went on to describe his role as “giving as little trouble as possible” and being “the humble chronicler.” I relate to his experience. Once we started climbing, I went from team leader to just the writer, trying to keep up and not hold anyone back.

As we climb, Jordan takes an active role in leading. He and Valentine take us up more difficult lines. I constantly find easier routes to the sides of those they’re choosing. This is not the path of least resistance; it’s an expression of ability. Ben, to my surprise, is a bit gassed himself. He confirms my observation that Valentine and Jordan are choosing lines beyond the necessary difficulty. It’s starting to feel like a competition. But in order to safely get off this mountain, we have to do this together.

~~

Although he was celebrated during his life, so much of who he was remained hidden until after his death.

Young was a conscientious objector during World War I, but he still served on the front lines in the Friends’ Ambulance Unit, a volunteer emergency medical service. Even after having his right leg amputated at the knee during the war, he would climb for the rest of his life.

After the war ended, he married his longtime friend, Eleanor “Len” Slingsby, and had two children, a boy and a girl. The relationship between Young and Slingsby shocks me. Hankinson highlights, “Before they married, Geoffrey told Len that he was homosexual. He had no expectations, presumably, that marriage would bring that side of his life to an end … The news must have been a shock to Len, but she determined to accept it. Geoffrey did go on having homosexual affairs, discreet and occasional, after the marriage … Long after Geoffrey’s death, when I had made friends with Len, I once summoned up the nerve to ask her if he had been homosexual and her eyes filled with tears before she replied: ‘Yes, he was.’”

~~

Turning back to the time that Young and Mallory spent together — the week in Venice the first year and a whole season of climbing the Alps in the second — I can’t help but interpret those days as suggestive of a grander romance, even though there is no written proof.

It’s impossible to know what happened during the time Mallory and Young spent alone together. What little documentation remains of their homosexuality is riddled with heartbreak and loss. After losing his leg, Young wrote to Mallory in a private letter, “I count on my great-hearts, like you.” Allow me to imagine the tenderness in that letter coupled with the picture that I carry in my pack.

As I look out to the jagged rocks of Aiguille Verte, I can almost see Geoffrey and George climbing together on the Moine Ridge, forging a bond that lasted their lifetimes and beyond, calling me here and informing this moment. That imagining is now as real to me as us standing here on the ledges of the Grépon. The knowledge that queer men in the early 1900s completed climbs so significant, so difficult, thrills me. I’m touching the very granite they did. I hope that in the only place where society allowed them to be together, for a brief moment in their lives, they shared gay joy.

~~

The pitches get much harder as we near the summit. Jones’ trip report illustrates Young and his teammates standing on each other’s heads to get to the next hold, with Young even saying that he “could not be expected to get up with such a handicap.” I empathize with his exertion, his reaching his own limits. Knubel pushes them toward the first ascent with “one of the most remarkable climbing feats I know of,” Jones writes with a tone of awe.

Right before the final pitch, I run out of water, a major risk considering we’re not yet halfway through our climb. Jones details Knubel’s final push for the summit as being “so excessively difficult as to make it unsafe for anyone to lead who was not master of the ice-axe hold … The rest of us watched with breathless interest Knubel’s violent struggle … using his ax … with the handle inserted between two stones as hand-hold, which finally landed him on the summit.”

At this final crux, I falter. Trying to propel myself out and over the Knubel crack, I fall into the void, dangling thousands of feet above the glacier.

Expedition leader Lance Garland makes a push for the summit of the Aiguille du Grépon. Photo: Ben Tibbetts.

But I’m not leading with an ice-ax. Our modern tools keep me attached to the mountain. Jordan holds me aloft. Quickly and without hesitation, I see my line, grab my holds, and shoot myself up to the summit. Young in his day didn’t have that kind of support net. But Jordan and I are able to ascend this peak in a way unprecedented to Young in his time.

Reaching the summit of the Grépon feels like a dream. Time slows with my breathing. Jordan and I share a high-five, and I move to a small open spot next to a statue of the Madonna. Although I’m not religious, her presence gives this summit a spiritual feeling, inspiring me to pause and soak in this hallowed place. Mont Blanc is to the south of us, its expansive massif spreading out in snow-covered peaks we haven’t been able to see until now.

I hope that in the only place where society allowed them to be together, for a brief moment in their lives, they shared gay joy.

At the sight of Aiguille Verte from this height, a new viewpoint shifts my understanding. I was so focused on whether George Mallory and Geoffrey Winthrop Young were lovers I didn’t see the larger fact that regardless of whether they were romantic or even aware that the other was actively engaging in same-sex love, that as far as I’ve discovered, they are the first known queer climbing duo in history.

The fact that they climbed over a century ago steals my breath. Here is the thing I’ve been looking for: It was never about a singular queer figure but about our connection to each other, not just now, but across time. I look over to Jordan, smiling, and realize we represent a strand of that very thing one hundred and thirteen years later.

“Thank you, Jordan, for this.”

“Don’t thank me yet; we still have to get off this mountain.”

It’s 3:30 p.m., and we’re only halfway through our objective.

The team pauses for a selfie on the summit of the Aiguille du Grépon. For Lance (foreground), the expedition and this moment have been a year in the making. Photo: Lance Garland.

~~

The descent introduces me to a new state of suffering. I experience severe dehydration, a fall that I barely save myself from, and delirium.

Sometime near 11 p.m., Jordan leads me down a side trail to what he excitedly calls “the promised land.” It’s a hollowed-out log flowing with spring water. I drink a liter of its cool promise and fill up my Camelbak to carry away. It is my first drink in about seven hours. The water hurts my body, and it rejects it. I sit on a boulder and retch five times.

In a few days, Jordan will tell me, “Valentine was waiting at the fork in the trail to the spring, making sure that we found water.” She was a quiet yet pivotal figure in this climb, and her example illuminates another person, Len Winthrop Young, Geoffrey’s wife, a celebrated climber and educator herself whose story is often overshadowed. Although we can’t do her story justice here, I want to honor the fact that it is because of her honesty that we have a truer picture of who Geoffrey was; she is a part of queer history as well, like Valentine in this project. In a few days, I’ll get to know Valentine more on a trail by an alpine lake, and she’ll tell me, “My grandfather came out as gay later in his life. My mother had a hard time figuring out how to deal with that.” Perhaps Valentine joined this project to understand more about him, about her own ancestry. In that light, I start to see queer history as universal: We are a part of the larger community, connected on the rope team of history.

On July 26, two days after summiting Aiguille du Grépon, Lance and Valentine converse by Stellisee, a famous lake in Zermatt, Switzerland. Photo: Ben Tibbetts.

On the trail, Jordan goes on ahead, then wakes from a brief nap, scared that he’s lost me. I tell him, “As a firefighter, I’m normally the one to take care of people. The roles have been reversed.”

Too many times after massive solo ascents on El Capitan, he’s had to descend alone and in bad shape. “I won’t let you do that tonight,” he assures me, like a protective brother.

It was never about a singular queer figure but about our connection to each other, not just now, but across time.

Since leaving the hut this morning, we will traverse over 10,000 feet of elevation, and it will take me and Jordan 23 hours to complete the climb due to my physical state. In the end, a diverse team of imperfect people accomplished the mission with our own mixture of identity and camaraderie. I hope that by carrying these stories with us over this mountain — along with these now-tattered pictures of Halliburton, Mallory, and Young in my pack — that we’ve honored these men with something they were never given in life: acceptance for how ineffable they were. This climb celebrates the singular ways they chose to live their lives against the odds and despite the challenges.

~~

Back on the summit, all three team members have rappelled using the Madonna statue as an anchor, leaving me alone on the Grépon for a moment as clouds envelop this ridgeline. With my hand on the Madonna’s shoulder, I enter a dual state of presentness and reverie. Had I known at the time how much would be required of me to accomplish this — the suffering, the changing plans, the risks, the work — would I have done it anyway? Unwaveringly.

Here I stand deeply rooted in queer history — in the same place where my predecessor, Young, made the first ascent. I can almost see his smiling mustache, like mine but bushier, being tickled by the wind. A smile spreads across my own. Beyond the valley, Aiguille Verte is vivid to me now, as is the relationship of the first known queer climbing team in history, Geoffrey Winthrop Young and George Mallory. Jordan and I have added a page to that story here on this crest, as have Oliver and I, with our engagement on this same massif. What this will mean to others, I cannot say, but to me, alone on the needle of the Grèpon, I inhale this sweet alpine air differently, now steadfastly belayed to a shared lineage.

Lance and Jordan share a moment of celebration at the Aiguille du Grépon summit, reflecting on what it might mean for two openly gay men to follow in the footsteps of Geoffrey Winthrop Young. Photo: Ben Tibbetts.

Additional support for this project was made possible from the 2023 Mountain Writing Residency at the Banff Center and a 2024 Catalyst Grant from the American Alpine Club. With ample historical findings, Lance is working on a book about the queer pioneers of alpinism.

Lance Garland

Lance Garland is a 2024 Pathfinder Prize winner and expedition leader for “Beyond the False Summit: A Matterhorn Expedition to Unearth the Queer Pioneers of Alpinism.” In the moments between fighting fires, climbing mountains, and sailing seas, he writes.