Support Hidden Compass

We stand for journalism, science, history, and hope. Make a contribution to Hidden Compass and stand with us.

The taxi driver glared at me when I demanded that he use le compteur.

“What do you think that is?” he snapped in French, pointing at the already-running meter under his dash.

Looking both pained and angry, he glanced into the rear-view mirror at another passenger already in the back, then turned again to face me.

Switching to English, I apologized as I got into the front seat of his bright-red petit taxi, explaining that every other driver in Marrakesh had insisted on an inflated price for tourists like me.

“Are you a tourist?” he asked, his voice still raised, chiding me. “Aren’t you living here?”

I wasn’t sure how to answer.

I was halfway into a two-month stay in Morocco, traveling with my wife who was there for work. During the days I explored and occasionally offended taxi drivers. I knew just enough French to get myself into trouble and often needed English to get out of it.

“Yes, I’m living here,” I answered the taxi driver, but it felt like a lie.

“There’s a saying in Morocco,” he said as he drove. “If you stay in a place for 40 days, you become one of the people.”

When I responded that I would be in the country for nearly 60 days, he peeked at the other passenger again, this time with a twinkle in his eye, and laughed.

“Then you will be Moroccan and a half!”

~~

Before leaving the U.S., I’d read somewhere that Moroccan men don’t wear shorts because it’s rude to show one’s knees. So, I packed three pairs of lightweight slacks, along with good leather sandals to walk in. With the right clothes, my trim beard, and my fast-tanning skin, I looked forward to blending in.

When I responded that I would be in the country for nearly 60 days, he laughed. “Then you will be Moroccan and a half!”

But my first morning in Morocco felt too warm for slacks. I stepped out of my modern hotel into the streets of Rabat, the capital, wearing a t-shirt and knee-length cargo shorts, and headed toward the medina—the city’s walled, medieval neighborhood.

I soon met a young European man who, before I’d said a word, exclaimed, “You’re American!” Pointing at the steel cylinder in the side pocket of my day pack, he said, “only Americans carry water bottles.”

The bottle would have to go, I decided, clinging to the hope that I could somehow blend in.

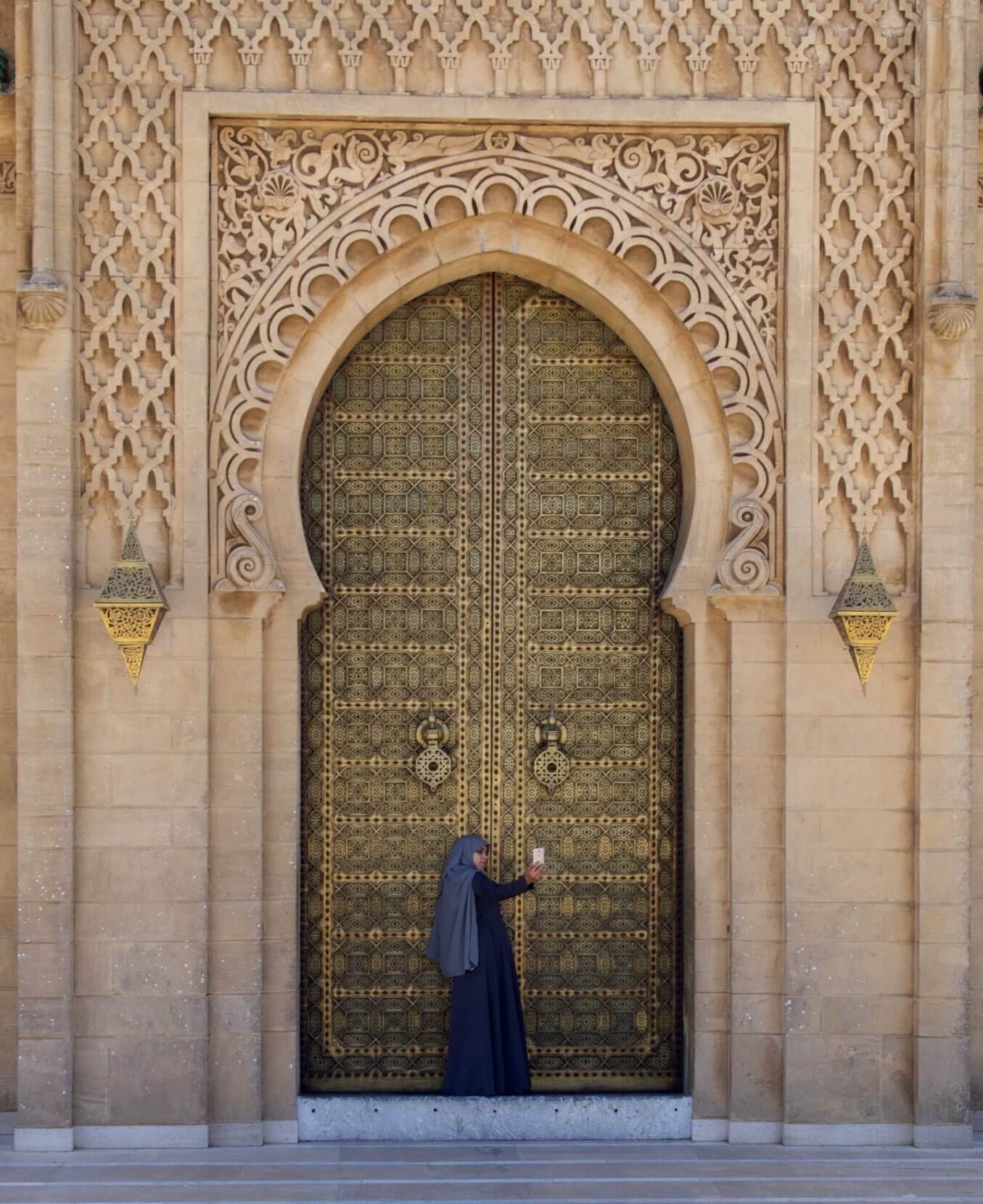

Woman in traditional dress pauses for a selfie at the Mausoleum of King Mohammed V in Rabat, Morocco. PHOTO: MIKE BERNHARDT.

As I passed for the first time through an ancient arch into the medina, my nostrils were bombarded by the aroma of fresh bread, mingled with the stench of putrid puddles on the broken pavement. I was surrounded by men and women wearing traditional djellabas and kaftans as well as sports coats and fashionably-torn jeans. An old man sat behind a water-stained, wooden cart laden with a rainbow of fruits and vegetables. My ears filled with Arabic, in which merchants bargained with customers and young men argued fiercely, seemingly about to break into a fistfight—about the previous night’s Barcelona-Madrid football game, I later learned. And then there were cats, feral yet friendly and fearless. They were in doorways, on countertops, and at my feet.

Cats on a street in Chechaouen, Morocco. PHOTO: YVONNE LEFORT.

The call to prayer bellowed from the nearest minaret and I watched as a shopkeeper pulled out a prayer rug and vanished, dropping down behind his counter to pray. For the first time since my 20s, I felt the joy of freely exploring an entirely foreign place.

But after two weeks, I had been accosted by so many street hustlers and shopkeepers that I was afraid to even look around me. On the more-touristed streets I was bombarded with “English? Français? Español? Come have a look!” And in the quiet back alleys, where children played, and old men greeted me with a smile and salaam alaykum, tween boys would assume I was lost, and insist on guiding me back to the main road, demanding money for their help. I felt like a walking wallet.

Why can’t these people just leave me alone?

~~

By the time we got to Tangier, I needed a haircut. After much broken French and many incomprehensible answers, I was finally directed to a neighborhood in the ville nouvelle — the modern part of the city — called Mozart, where a third of the shop windows were decorated with faded-blue posters of handsomely coiffed young men. I picked one of the hair salons and showed the stylist a photo of myself with shorter hair, telling him comme le photo, s’il vous plait — “like the photo, please.” But when he put a huge electric shaver to my head, my heart sank.

The stylist not only cut my hair, he trimmed my eyebrows, massaged my face, and put gel in my hair. I had never used hair gel in my life. My hair looked nothing like my photo. It had been trimmed down to near-nubbins everywhere but on top. I had been given a typical Moroccan haircut — for a man half my age. But I liked it. It seemed … less foreign.

Later, I took a seat outside a café in the famous Petit Socco (Little Market) at the heart of the medina. Savoring my creamy and fragrant café au lait, I relaxed into the moment.

An enormous group of Spanish tourists gathered, led by a guide in a light-blue djellaba and yellow leather slippers. Men carrying pendants, scarves, plates, jewelry, and handbags simultaneously materialized around the group, enthusiastically offering their wares. An older American couple, clearly exhausted, sat down next to me. The husband ordered a beer. More vendors appeared like vultures, as the husband paid asking price for belts and souvenirs.

I had been given a typical Moroccan haircut — for a man half my age. But I liked it. It seemed … less foreign.

For a long time, I was ignored, as if I were audience to a play acted by everyone else. Eventually a vendor came over, offering me a small, solid brass camel. I picked it up, admired its heft, and politely declined. The American husband, who by now was complaining loudly that he had no more money, gave me a tired smile.

He pointed at the camel and said, “You may as well buy it, you won’t be able to tomorrow.”

“Actually, I can buy it tomorrow,” I said.

The camel hawker’s attitude toward me immediately changed. “I’m sorry if I’m bothering you,” he apologized. “I’m just trying to make a living.” I smiled, told him not to worry about it, and he left.

I sat quietly. Waves of tour groups washed up Rue de la Marine from the Mediterranean, appearing hopelessly out of place. Suddenly, the Petit Socco seemed bathed in a new light, and I was filled with newfound respect for the hawkers and aggressive shopkeepers just trying to make a living. My face flushed as warmth and affection swelled in my chest, radiating into my extremities and out toward the denizens of that square.

Eventually I paid for my coffee and walked down the hill toward Tangier’s port.

“Where is your wife today?” a man’s voice called out.

I vaguely recognized him; he reminded me that my wife and I had visited his jewelry shop almost a week earlier when we’d “had a look.”

How did he remember me out of thousands of tourists? I wondered. He didn’t ask me inside. Instead, we talked for a while and then parted warmly, hands on our hearts in the Moroccan way.

The next afternoon, I went back to the same cafe. The camel-hawker happily recognized me, and we exchanged pleasantries; buying something was never mentioned.

In the evening, my wife and I had dinner at my favorite local restaurant where Abdul, the owner, sat down with us and where we talked for hours about life, love, and children.

I no longer felt like a tourist. Perhaps, I thought, the taxi driver in Marrakesh had been right about becoming one of the people.

~~

Near the end of our time in Morocco, in the artsy fishing town of Essaouira, we were invited by a man we met at a local gallery to share ftour — the sunset meal that is celebrated each night during the month of Ramadan — at his home. That evening we felt like extended family. We enjoyed the relaxed conversation with our host and his teen-aged children while his wife cooked non-stop, coming out of the kitchen only once in a while to bring more food, or eat, or interject a comment. Our host’s daughter had spent a year abroad in the U.S. and excitedly telephoned her “American mother” to introduce us.

Afterward, as our new friend drove us back to our hotel, I thanked him for honoring us with his invitation.

“No, the honor is mine!” he replied. “The Quran says that inviting someone to your home for ftour is better than going to the mosque to pray.”

The next day, I passed the store of a nomadic trader who dressed the part in a brown robe and black turban. Tables were covered with cheap jewelry and assorted junk. He showed me a silver pendant that I didn’t want, offering it to me for only 300 dirhams, about $30. I should have said, “I’m not shopping today,” but I felt inspired. And cocky.

“It’s beautiful, but I only have 10 dirham. I know it’s worth much more than that, I’m sorry.” I said and continued down the street.

He came bursting out of his shop, shouting, “OK, OK, 10 dirham!”

Aww, crap. I should have handed over the money, but rather than pay a dollar to keep the peace, I admitted that I didn’t actually want the pendant at all. The shopkeeper yelled at me for retracting my offer.

Maybe I hadn’t become Moroccan after all.

As I reconsidered my desire and efforts to blend in, I realized that I was never going to become one of the people. But the people I met along the way — at least the ones I hadn’t offended — welcomed me as a friend.

That was more than enough.

###

Feature photo credit: Yvonne Lefort

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story mistakenly quoted the man from Essaouira who invited the author home to share ftour as referring to the Prophet, rather than the Quran.

Mike Bernhardt

Mike Bernhardt is an eclectic writer who loves the water, be it diving coral reefs in Indonesia, swimming with sea lions in the Galápagos, or researching drowned ancestors off the coast of Ireland.

Never miss a story

Subscribe for new issue alerts.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive updates from Hidden Compass regarding new issues and other ongoing promotions such as workshop opportunities. Please refer to our Privacy Policy for more information.