Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

Paule de Viguier lowered her eyes as she moved through the crowded streets of Toulouse, her hands delicately picking up her white dress so it hovered slightly above the ground, away from the muck of the slanted cobbled street. Topped with a crown of red roses, her golden hair gleamed in the hot August sun.

In her hand was the key to the gates of the city, which she was to deliver to King Francis I.

When she and the other nobles of Toulouse reached the front gate, Paule paused and quickly lifted her eyes to the royal entourage in front of her. Servants and courtiers announced the king with banners. Francis himself rode under a large fabric canopy held by servants, wearing a hat with an ostrich plume and a brocade of rich fabric. The royal courtiers followed on horses, a procession worthy of the power and wealth of the French monarchy.

The year was 1533, and it was the first time the king of France had come to Toulouse. For all its pomp and pageantry, the momentous affair could be traced back to a little green plant growing like a weed on the side of the road. Known as woad in English or pastel in French, it’s the same thing that brought me here nearly five centuries later.

~~

On another blisteringly hot day, 487 Augusts later, I peered into a massive steel pot, a smaller pot inside. A thick film on the surface obscured the dye burbling below, so dark it was nearly black. A strong odor stung my nose, its pungency catching me by surprise.

As a hobbyist watercolor artist and history lover, I became transfixed by pastel after reading The Secret Lives of Color. I was eager to try my own hand with this plant material that has been said to make blue dye since at least Roman times, when, according to one translation of Julius Caesar’s account, the Celts may have painted their bodies with woad.

Soon I had found my way to southwest France. At Terre de Pastel, a low-slung concrete building that houses a cosmetics boutique and a museum dedicated to its namesake plant, I signed up for a tie-dye workshop alongside a dozen or so French tourists.

Our workshop leader, Marie, wore a pastel-dyed apron, her fingers stained dark blue. After ushering us through rooms plastered with timelines and photos of woad, she showed us to a room lined with tables and large metal vats in the back of the building. That’s where the fun began.

A strong odor stung my nose, its pungency catching me by surprise.

Her dark hair pulled back, Marie spoke rapidly and authoritatively. Making her way around the room, she showed us how to submerge cotton bags in the vat, and how to make sure bubbles didn’t form on the fabric — which would lessen the intensity of the dye.

The blue of the final product depends on many factors, including how the dye is prepared and how long the fabric is saturated. In fact, pastel blue renders 13 distinct shades — from the pale blue of a winter shadow, to a faded robin blue, to a deep navy.

But that’s not how it starts.

“Look at the color,” Marie told us after we had left the bags to soak.

I peered into the vat, spotting my bag bobbing among the others. Using my fingers, I pulled on a string attached to the cloth and was amazed by what emerged. From the depths of the dark dye, my bag had taken on a sunny hue — yellow green, like the surrounding Occitanie countryside.

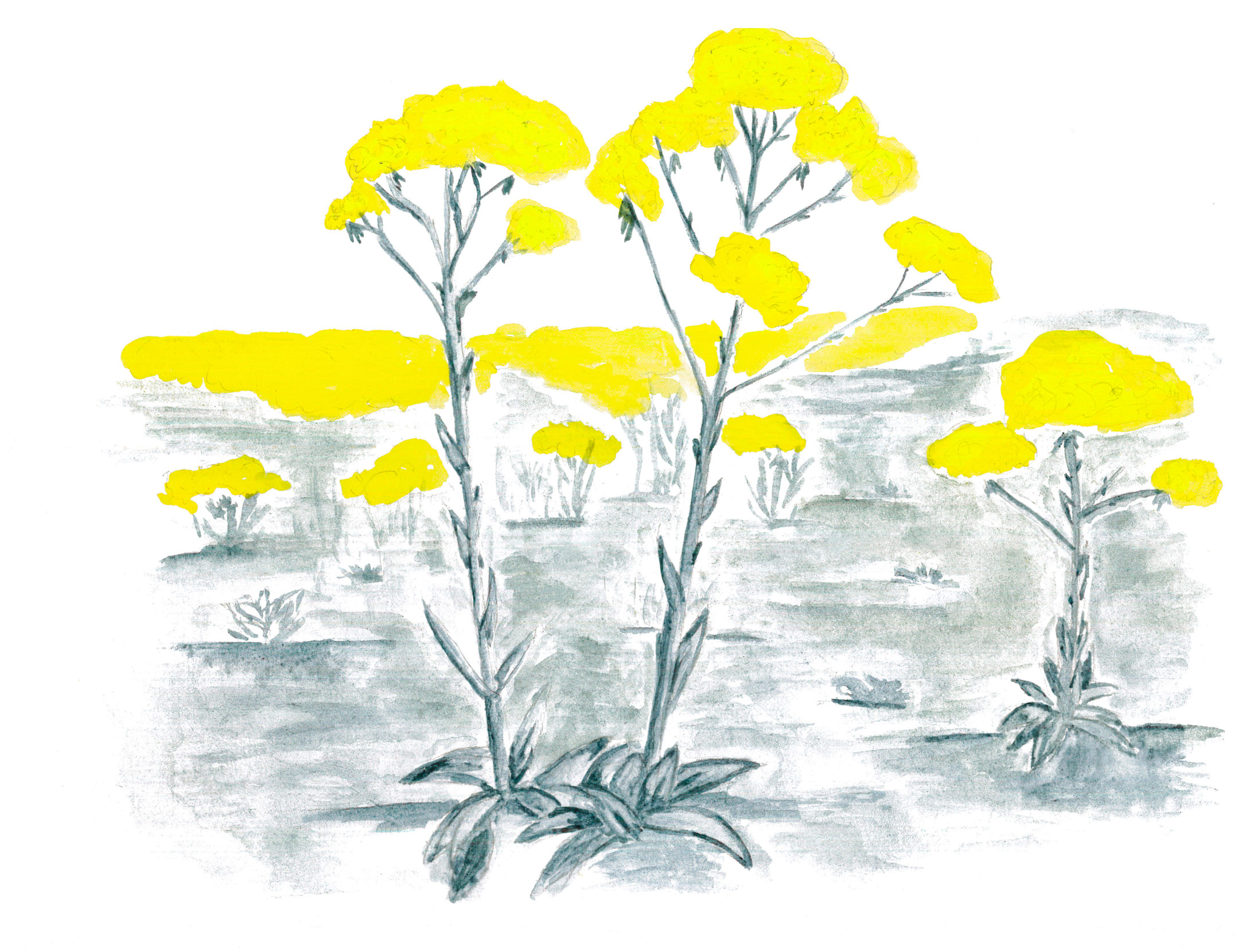

The leaves of Isatis tinctoria — known as woad in English and pastel in French — are processed to create an indelible blue dye, which the author/artist turned into watercolor to create this illustration. Clusters of delicate yellow flowers bloom in the plant’s second year. Artwork by Moriah Costa.

Only when the dye is exposed to oxygen, Marie explained, does it begin to take on the blue tint for which it is famous.

When it comes to pastel, I was starting to realize, what you see is not always what you get.

~~

As the royal entourage marched to Toulouse in 1533, they slowly proceeded across dirt paths past miles of farmland — the thin, jagged leaves of the pastel plant withering in the summer heat, ready for harvest.

In the limestone-rich fields of the Lauragais region, outside of Toulouse, entire families moved from farm to farm as hired hands, picking the veined leaves just as the edges began to turn purple and carefully sorting out any weeds — one stray leaf would diminish the dye’s potential. Once plucked, the leaves were transported to one of hundreds of area mills. Granite stones crushed the leaves into a pulp, which was rolled by hand into hard balls — called cocagnes — and laid out to drain. Once dried, these cocagnes were crushed again into a powder and then left for months to ferment with human urine and stagnant water. The stench was horrendous, but this arcane alchemy created a potent pigment.

Only when the dye is exposed to oxygen … does it begin to take on the blue tint for which it is famous.

The hardened rocks of paste were then packed into thick cloth bags, loaded into carts, and driven to Toulouse. There, merchants checked the quality; only the pastel left to ferment the longest produced the strongest dye and fetched the highest prices in London, Antwerp, and elsewhere.

In this sweet spot between sea, ocean, and mountains, pastel flourished. Its arduous production method was a closely guarded secret. Connecting Toulouse northwest to the port of Bordeaux, the Garonne River bustled, carrying ships and barges full of wine and pastel, hope and prosperity.

Pastel merchants, who owned the farmland and controlled every step of production, grew their fortunes on “blue gold.” Wealth permeated the region. The nearby town of Albi raised funds to paint extravagant murals and frescoes in its cathedral; local lore once maintained that the brilliant blue adorning its vaults was from pastel itself.

Toulouse, which had suffered a destructive fire in 1463, blossomed with private mansions — vast spectacles built of pink-red brick featuring massive towers, ornamental columns, and elegant courtyards.

As the pastel trade boomed, the staid town of the Middle Ages, lined with half-timbered houses, emerged as an anchor of the Pays de Cocagne. That nickname, derived from those balls of pastel, soon became shorthand for the Land of Plenty.

~~

When I brought up pastel to my in-laws, who have lived near Toulouse for three decades, they suggested it was something for tourists. But when it comes to history, I’m not easily detracted.

In the center of Toulouse — still called La Ville Rose for its prevalence of pink brick — the Renaissance legacy persists. Small alleyways and streets zig and zag haphazardly, never following a straight path for long.

Among a mash-up of historic edifices and modern windows, I arrived at a massive stone doorway. Swirling inscriptions and a huge iron knocker obscured the treasure it protected — the Hôtel d’Assézat, one of the few remaining private mansions built by the Renaissance pastel merchants that is still open to the public. I had walked by the door many times on my trips to Toulouse, with no idea of what lay beyond.

When I finally entered the mansion, I froze, staring up in awe at its massive staircase tower. The building itself is shaped like an L, but its walls are designed to create an inner square, surrounded by windows. Framing each of those windows are columns that get smaller the farther up they go — a trick used during the Renaissance to create an illusion of depth.

Built starting in 1555 as the family residence of a pastel merchant, the mansion now houses an art museum containing Western art from the end of the Middle Ages to the 20th century.

As the pastel trade boomed, the staid town of the Middle Ages, lined with half-timbered houses, emerged as an anchor of the Pays de Cocagne.

As I wandered from room to room, ogling bronze sculptures and landscape paintings, mahogany cupboards and imposing desks fitted with marble, I caught a glimpse of what life might have been like as a wealthy Renaissance merchant.

But what struck me the most was that there was no celebration of the man who made this opulence possible — Pierre d’Assézat.

That omission, it turned out, was steeped in drama.

~~

As these stories often go, pastel eventually fell from grace. Another natural source of blue dye — indigo — arrived on the scene. Derived from a tropical plant with deep roots in Asia, indigo allowed for easier extraction of blue and yielded more concentrated dye. With the advent of new maritime trade routes in the 17th century, this blue alternative began streaming into European markets from India as well as from the New World — where it was often produced on the backs of sharecroppers and enslaved people, allowing for cheaper prices.

For a time, some countries resisted: In Renaissance France, the use of indigo was punishable by death.

By the 18th century, though, indigo had won out, and the overflowing cup of the Land of Plenty dried up. Napoleon Bonaparte attempted a revival when he chose pastel to dye his army’s uniforms in an attempt to evade British blockades. But as the empire fell, so did the pastel industry — this time for good.

French trade moved on to the Atlantic ports of Bordeaux, Nantes, and Marseille, where access to the sea eased the import of indigo and other goods.

Over time, pastel became all but impossible to find in and around Toulouse, its legacy forgotten by all but a few.

~~

On face value, indigo made an obvious villain. But my love of history has taught me to never accept a simple explanation. I knew there had to be more to pastel’s story. Anything wrapped up in that much wealth doesn’t tend to disappear without a fight.

In Renaissance France, the use of indigo was punishable by death.

So I turned to pastel enthusiast and historian Sandrine Banessy, who co-founded Terre de Pastel, where my tie-dye workshop had taken place. I wanted to know why the story of Pierre d’Assézat, the wealthy pastel merchant whose grand mansion still took my breath away several hundred years later, seemed to have slipped through the cracks of history.

Assézat was a Calvanist, Bannesy explained matter-of-factly. Like many Protestants, he was forced to flee Toulouse during the French religious conflicts at the end of the 16th century.

These Wars of Religion, she told me, led to an unexpected consequence in southern France: The booming pastel trade went bust.

Many merchants were Protestants or Jews and were chased out of town during the prolonged unrest and violence between Catholics and Huguenots from 1562 to 1598.

“It was really hard for Protestants in Toulouse, but people don’t want to speak about this,” Bannesy told me.

Her comments stuck with me as I continued to delve into pastel in southern France. Of all the villages and chateaux I researched and visited, I found scarce acknowledgment of the Protestant link to the pastel trade.

On a quiet side street in the cobblestoned village of Sorèze, I finally encountered a public nod to this fraught connection: a small plaque mentioning that many pastel dyers during the Renaissance had been Protestants. It stood as silent testament, out where anyone could see it. The few tourists around me, though, walked by without a glance.

~~

In Toulouse, my husband and I ambled along the promenade next to the Garonne River. The breeze coming off the water hit my face as we crossed the Pont Neuf, a stone arch bridge built over several decades starting in the mid-16th century — a relic from pastel’s heyday.

As I walked across the cobblestones of the Capitole square near where pastel merchants would have made their deals, I tried to imagine what these streets would look like new. Around 50 of the private mansions remain. Some are divided into apartments or elegant offices, with street-level shops selling shoes, clothes, or chocolates, much like the merchants’ quarter of the Renaissance. Many have been demolished, or so significantly renovated that they are hard to recognize. One is on the verge of decay; a sign from the city says it’s been found unfit for habitation.

Pastel merchants, who owned the farmland and controlled every step of production, grew their fortunes on “blue gold.”

Another day, I got into my mother-in-law’s car, and the two of us headed to Château de Magrin in the Tarn region, near Toulouse.

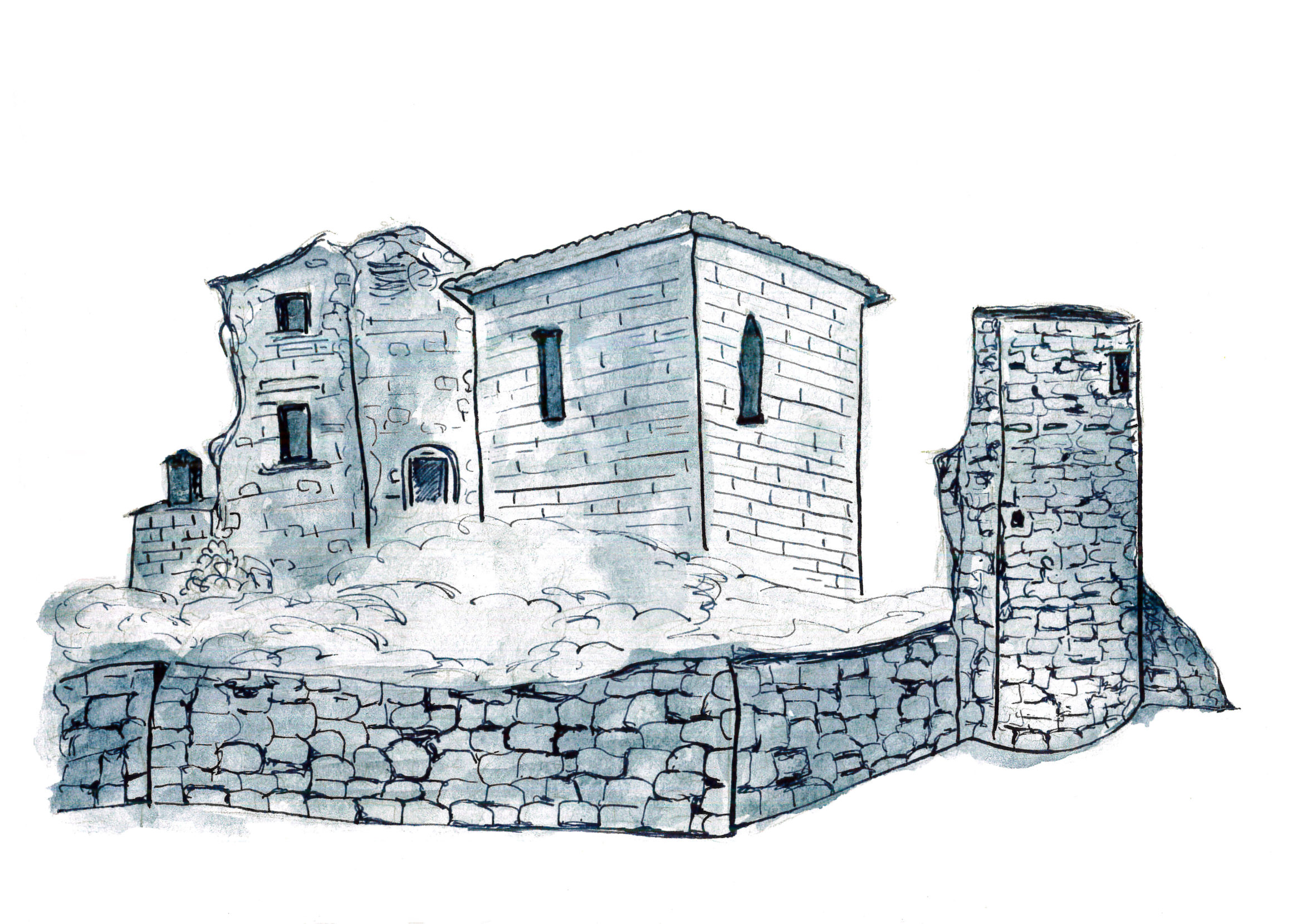

Like the story of pastel, the chateau required some perseverance to find. We almost missed the sudden turn down a long, winding road through fields of sunflowers and wheat. Magrin sits on top of a hill, its once massive walls crumbling.

The chateau is a hodgepodge of architectural styles, having been rebuilt and added to many times since the 12th century. The oldest part, which houses a section of the museum, is a plain brick building of simple proportions. Boards cover many of the windows.

In 1971, historian and journalist Patrice Georges Rufino purchased this abandoned chateau. While renovating the building, he discovered a long room fitted with narrow shutters and filled with rusted wire racks. His curiosity piqued, he figured out that the racks had been used for drying pastel balls. The French government recognized the chateau as a historic monument in 1979 and, a few years later, Rufino opened a small pastel museum inside.

Like the story of pastel, the chateau required some perseverance to find.

Today he and his wife, Hélène, serve as steady stewards of pastel’s agrarian past. They grow pastel in the courtyard to show the occasional visitor. Hélène gives tours of the estate, a pastel-dyed shawl shielding her sun-weathered skin. There’s also an original mill, a formidable granite wheel used to crush pastel leaves. Faded mannequins of a farming couple and their horse stand at its helm, their period-appropriate clothing coated with dust.

First the author visited Château de Magrin and learned its pastel history; then she made watercolor out of pastel pigment and rendered the centuries-old building a vision in blue. Artwork by Moriah Costa.

In town, my thoughts gravitate to pastel’s economic impact and the cultural renaissance it created. Nobody can say for certain how much wealth the pastel trade created, but without pastel, there would have been no lavish pink-brick mansions, which still draw tourists who bankroll Toulouse’s economy. We can account for that.

Out in the country, pastel’s story remains rooted in its bounty — the power of its leaves to reshape a region, the potential for release that came with the harvest.

~~

In 1533, the abundance of pastel appeared limitless as 15-year-old Paule de Viguier curtsied and demurely handed over the brass key to the city, her almond eyes downcast. Francis opened the gate and entered Toulouse, his entourage escorting him to the stately private mansion of Jean de Bernuy, where a freshly erected hexagonal tower rose over the city. Most likely, the nobleman entertained the king among the arches of the courtyard, in which embedded medallions immortalize the likenesses of Bernuy and his contemporaries.

The king had come all this way to say thank you.

Eight years before, the monarch had been captured in Italy’s Battle of Pavia and left a prisoner of his rival, the Spanish king and Holy Roman emperor Charles V. As part of a high-stakes deal ceding land control, Francis had traded his sons for his own freedom.

In 1529, Charles V had set an extraordinary ransom for the release of the child hostages — two million gold crowns. Bernuy, a merchant who had amassed an immense fortune in the pastel trade, had offered up the lion’s share of the sum.

Because of a humble plant easily mistaken for a weed, the story goes, the heirs to the French throne no longer languished in prison.

~~

Back at my apartment in Madrid, a special package arrives from overseas. I eagerly cut through its careful packaging and examine its contents: a small plastic bag of pastel pigment. Immediately, a dust of blue powder coats my dining room table and, upon contact, turns my skin blue.

I was eager to try my own hand with this plant material that has been said to make blue dye since at least Roman times, when, according to one translation of Julius Caesar’s account, the Celts may have painted their bodies with woad.

Procuring this pigment was no easy feat, but eventually I had tracked down a vendor based in the U.K. that would ship me some. I planned to turn the powder into watercolor.

The process requires a blend of science and art, patience and hope. I place some pigment powder on a small glass slab and add an equal amount of gum arabic (to act as a binder), a drop of thyme oil (as preservative), and a dash of honey (to help it retain moisture). Using a glass espresso press, I begin mixing, squishing the pigment and binder together over and over, until the consistency is just right.

Woad, I discover, is quite sticky. The more binder I add, the more the pigment soaks it up.

More than an hour passes like this: me struggling to tame this musty powder into a manageable paste that can be dried in watercolor pans. I look at the sticky mess in front of me and think about the strange and fascinating alliances we make with history.

Later, I dip the bristles of my paintbrush into the finished watercolor. As I commit pastel to paper, I carry on its vast legacy of boom and bust, promise and peril. With each brushstroke, I unlock a piece of the past.

Moriah Costa

Moriah Costa is a freelance journalist and editor by day and an artist by night.