Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

Our journey began in 1997 with an old, hand-bound book, its thick, padded covers wrapped in light-green fabric embroidered with a pattern of cracked glass and flowers. We found it hidden under a sweater in Margaret Hansen’s dresser drawer.

By the time Margaret died at the age of 103, she had lived through two World Wars and survived her children, two husbands, and a 96-year-old boyfriend. Everyone, even her neighbors, called her Oma — German for grandma. Her eyes were gray and piercing but kind. They smiled when she looked at you.

Hunched with age, Oma stood about 4 feet 6 inches tall and tilted her head up to look forward. At 99, she danced to the Beatles’ “Twist and Shout” at my wedding with her granddaughter, Yvonne. Margaret rarely complained, often saying only, “What can you do?” in response to an issue. Few people knew her past and how much lay behind those words.

After Margaret died, Yvonne and I went through her belongings. That’s when we found the book, 14 inches wide and a foot tall. A piece of hand-tied, pale-jade rope held the cover and swollen pages to their binding. The spine was cracked, the front cover partly detached. Yvonne opened it and turned the yellowed pages carefully to avoid tearing them.

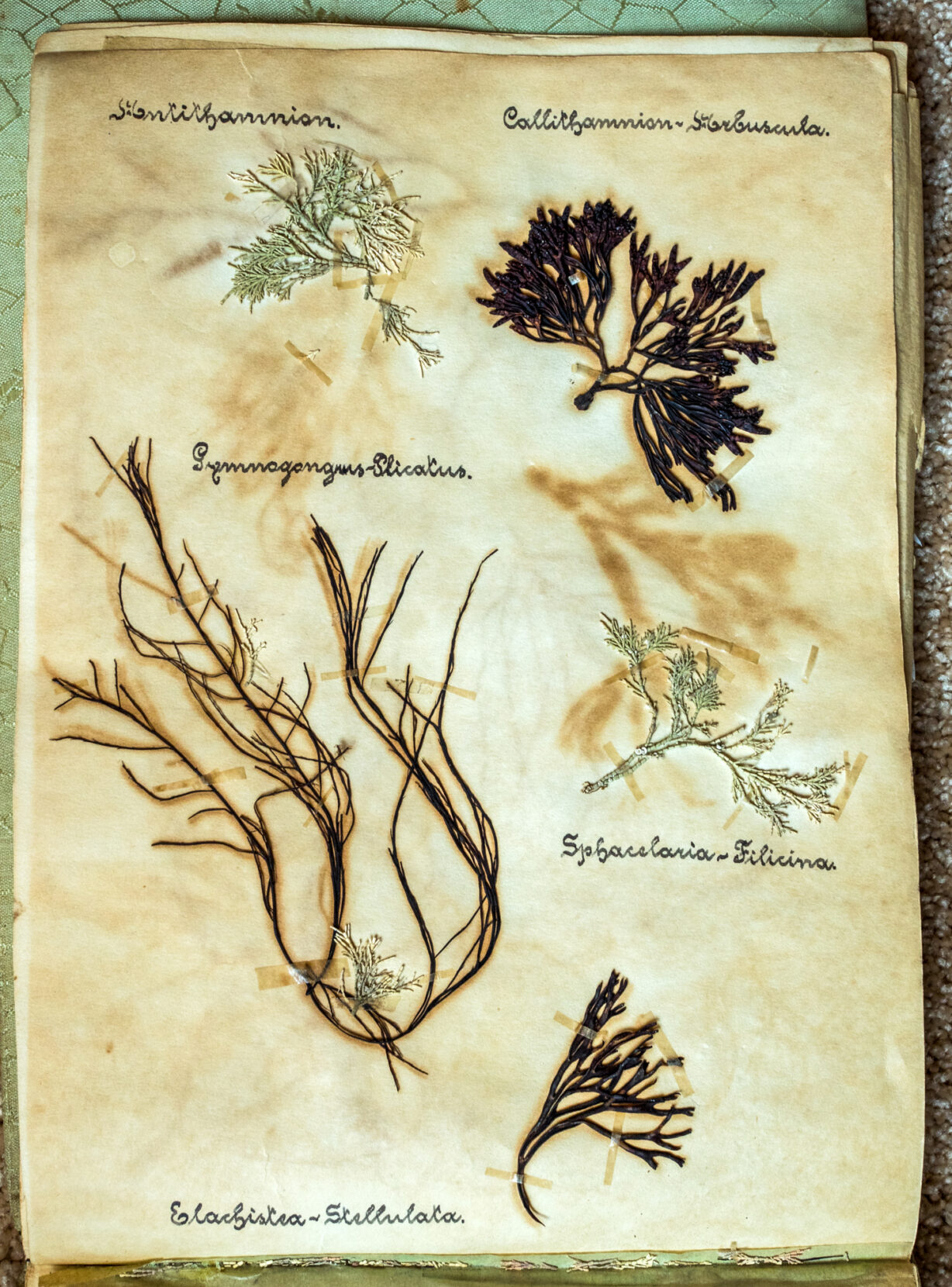

Page after page was covered with seaweed — dried, pressed, and mounted. Each page held a different variety; many, but not all, identified with Latin names written in Margaret’s neat, curlicued cursive.

Margaret Moser’s personal seaweed collection, carefully preserved and labeled in this hand-bound notebook, prompted writer Mike Bernhardt to spend decades and cross oceans to better understand her story. Photo: Yvonne Lefort.

~~

Thousands of miles away and 25 years later, Yvonne and I found ourselves battling a howling, relentless wind that flayed our faces with rain. Soggy peat bog gave way gently underfoot as we walked across green moss, pooled rainwater, and short grasses. Eventually, the ground gave way to rocky cliffs that dropped hundreds of feet to the sea, where roiling waves crashed over massive black boulders and tilted stone slabs.

“Why,” Yvonne would eventually ask, “do you care so much about what happened to my relatives?”

Yvonne had grown up hearing too much, too young, about her family’s traumatic past and had worked hard to put it behind her. Yet here she was, walking with me on the Mullet Peninsula in County Mayo, Ireland — a desolate place where weather, stone walls, and the wild Atlantic Ocean dominate the landscape. Scattered sheep and a few isolated hamlets punctuated the windswept terrain before us. I hoped to find answers there.

~~

Yvonne, even at only 5 feet, 3 inches tall, towered over her diminutive grandmother. Their conversations always began in English, but Margaret often slipped subconsciously into German. Fortunately, Yvonne speaks German, French, and Spanish — she majored in languages. In her 20s, she lived and worked in Germany for almost three years.

Yvonne grew up with hazy tales of Margaret’s life and losses during World War II, including vague mentions of gathering seaweed while interned on the Isle of Man. But she didn’t ask many questions, knowing that the answers might veer into Holocaust stories she didn’t want to hear.

It must have been bittersweet to keep a book of such beauty that was also a reminder of everything she’d lost.

By the time we found the seaweed collection, many details of Margaret’s life were still unknown to us.

We put the book in our fire safe, intending to donate it to a university or oceanography program, but we didn’t follow through. Years later, I began to wonder: What was the story behind Margaret’s seaweed? What happened to her and her first husband, Ernst, during the war?

~~

I have a photo of Ernst in a dark jacket, white shirt, and silk tie. His short, wavy hair is slicked back. A fine watch graces his left wrist. He’s looking proudly, sweetly, at an infant in his arms.

Ernst Moser was a salesman for his family’s paper-manufacturing company — the first factory in the world to make paper bags. His sense of humor endeared him to both customers and friends. “Wherever he was,” Margaret later remembered, “there was always laughter.”

Margaret was born into an educated, entrepreneurial family in northern Germany. During World War I, she became an X-ray technician and a nurse, caring for wounded soldiers at a hospital in her birth city of Hannover.

She and Ernst married after the war and had two children: a son, Kurt, and a daughter, Edith, who later became Yvonne’s mother. Edith remembered a childhood filled with laughter and music — Ernst was an accomplished pianist — as well as swimming and tennis during the summer. They were Jewish by ancestry but identified more as German, even keeping Christmas trees, like many secular Jews.

Looking at the photo, Ernst’s love for his family is plain. What dreams did he have for his children? I can only imagine the desperation he must have felt as those dreams collapsed.

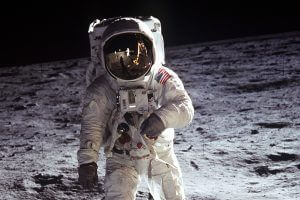

Ernst Moser gazes lovingly at one of his two children, in a portrait taken from a time of music and laughter. Photo courtesy of Yvonne Lefort.

~~

When Hitler came to power in 1933, Edith wrote, “little by little we learned that we were Jews, and Hitler didn’t like Jews.” Over the next five years, the Nazis gradually took everything from the family: their employment, their home and belongings, even their citizenship.

Ernst contacted relatives in New York to help him take his family to the United States. In early 1939, the Mosers handed teenage Kurt and Edith to a Belgian children’s rescue committee, hoping to keep them safe in Brussels until the family’s U.S. immigration application was approved.

That the Mosers even received visas was a miracle. In 1939, U.S. quotas limited immigration of German and Austrian nationals to 27,370. More than 300,000 people had applied.

When Ernst and Margaret left Germany for England in July, the Nazis only allowed them to take 10 Reichsmarks — $4 each — and their tickets for a White Star ship sailing from Liverpool to New York. The Mosers planned to reunite with their children in England and leave from there for the U.S. But it took too long, and on September 3 when Britain declared war, immigration to England ceased. The children were stuck in Belgium and the Mosers wouldn’t leave without them.

I can only imagine the desperation he must have felt as those dreams collapsed.

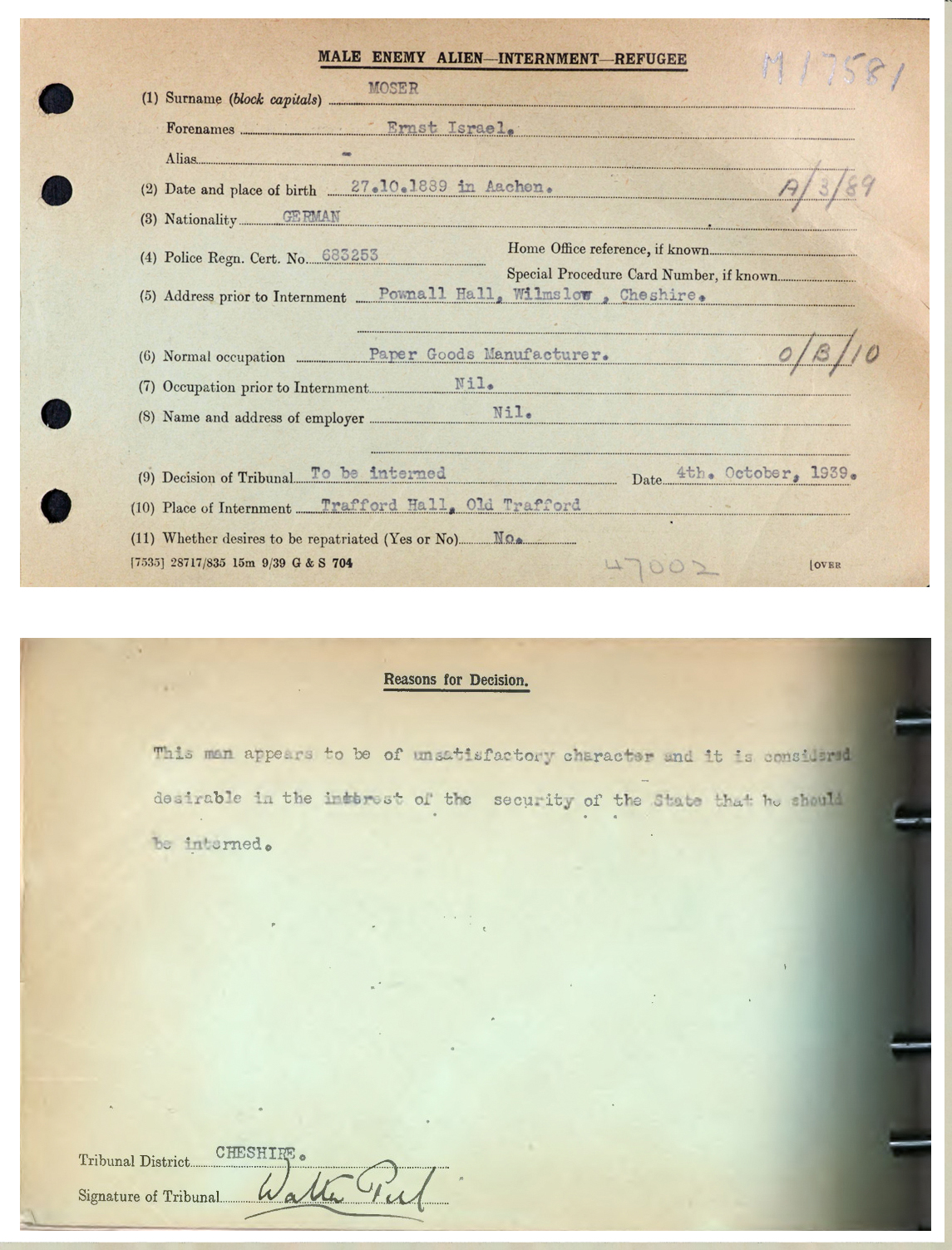

Days later, the British government haphazardly organized tribunals across the country to determine who among England’s 73,000 German and Austrian “enemy aliens,” mostly Jewish refugees, were security risks. With no prescribed standards, each magistrate made his own judgment.

Most tribunals documented Jewish defendants as “refugee[s] from Nazi oppression” and released them. Ernst’s determined, without explanation or mention of his background, that he “appears to be of unsatisfactory character and … should be interned.”

He was one of only 569 men who were arrested.

Of Britain’s 73,000 German and Austrian “enemy aliens” — mostly Jewish refugees — 569 were arrested. Ernst Moser was one of them. This card documents the magistrate’s finding in his case. Photo: Courtesy of the U.K. National Archives.

~~

In the summer of 1938, more than a half million British vacationers visited the Isle of Man, a British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea.

The village of Port Erin, in the southwest, was famed for its gorgeous beach and plentiful sunshine. Dozens of hotels and boarding houses lined the beachfront promenade and nearby streets. There was also a biological research station on the bay’s southwestern corner — an extension of the University of Liverpool. Scholars and students from all over the U.K. studied marine biology and the exceptional variety of seaweed drifting onto the Isle of Man’s shores. An on-site aquarium educated thousands of visitors each year. But vacationing paused with the onset of war.

~~

Margaret remained free after Ernst’s arrest, languishing without her husband and children. She took any employment she could find, but work was hard to come by — as the fear of invasion grew, so did rumors that even the most harmless-looking German refugee might be a “fifth columnist” waiting for Hitler’s signal to undermine the U.K.

Her freedom didn’t last. After Germany’s invasion of Belgium and Holland in May 1940, thousands more refugees were arrested. Margaret was sent to Rushen Camp — an internment camp on the Isle of Man, where barbed wire then enclosed the entire southern end of the island, including Port Erin.

The British government ordered proprietors of Rushen Camp’s hotels and boarding houses to accommodate more than 3,500 refugee women and children. Initially, there were food and housing shortages, and while the majority of internees were Jewish, some were Nazis. Jews and Nazis were sometimes forced to share rooms, even beds.

Conditions did improve over time. Housing was rearranged and women found ways to be productive. Margaret learned how to crochet shopping bags with old fishing line. Internees had freedom of movement within the fence, including access to the beaches.

Some hosts were upset that while their husbands were off fighting, or dying, their enemy charges were receiving a “holiday.”

~~

Wendy Thirkettle couldn’t stop smiling. She and I had been corresponding for years about Margaret’s internment, but we were meeting for the first time. Wendy welcomed Yvonne and me so warmly we felt like we were visiting an old friend.

Wendy is head archivist at the Manx National Heritage Library and Archives, housed in the Manx Museum, a century-old, red-brick building exhibiting history and culture dating back to the Stone Age. The library cares for a treasure-trove of documents, photos, and letters, many relating to wartime internment.

Yvonne and I were there to donate Margaret’s seaweed collection.

Wendy placed it gently on a cushioned stand in the brightly lit research room. In the background, other visitors typed on laptops and examined historical documents on modern gray tables.

“Oh, it’s so well preserved!” Wendy exclaimed, as she and Yvonne slowly turned the pages. “It’s beautiful! This will be unique in our collection, I can tell you that.”

Wendy invited the Manx Museum’s natural history curator to see the album. Observing the water-stained pages, she explained the process used to mount the seaweed: Margaret would have placed a sheet of paper in the bottom of a tray of water, then laid a piece of seaweed on top, allowing it to settle and spread. After adjusting the sample with tweezers, Margaret would have carefully lifted the paper out and let it dry. She probably made the covers, too, stretching and gluing spare fabric over cardboard, then binding it all together with decorative rope.

Wendy showed me a copy of the biological research station’s 1941 annual report. Among other wartime projects, they promoted the value of seaweed as a crop fertilizer. Internee volunteers like Margaret collected and distributed it for use in local farming and gardening. With time on their hands, a few women created their own collections, gathering, pressing, and cataloging dozens of species from the island’s bays.

Research station resources would have been invaluable to help Margaret identify her specimens, but her captions end about halfway through the album; perhaps she hadn’t finished when she was freed in late 1941. She carried the book through multiple addresses in England, though, and took it with her in 1948, to the U.S. It must have been bittersweet to keep a book of such beauty that was also a reminder of everything she’d lost.

~~

Here she was, walking with me [in] a desolate place where weather, stone walls, and the wild Atlantic Ocean dominate.

Over the following days, Wendy generously assisted us in our search for traces of Margaret’s time in internment. We learned that she had lived in two places: Snaefell, and Tower View on Ballafesson Road. But without addresses, even Wendy wasn’t certain of those locations.

Yvonne and I took a bus to Port Erin to explore the area and look for clues. We’d brought one more thing: a photograph of Margaret on the Isle of Man, dated Christmas, 1940. I hoped to discover where it had been taken. She is sitting, overlooking a picturesque bay or river. In the distance rises a grassy hill with a lone white house. Her hair is plainly coiffed and she’s wearing a prim, collared white shirt and dark necktie. A fisted hand rests in her lap. In her eyes, I see deep sadness.

Margaret Moser looks back at the camera in this photo taken overlooking Port Erin. Photo courtesy of Yvonne Lefort.

~~

The land of Ireland’s County Mayo isn’t very fertile. Much of it is rock-strewn bog, and few crops can thrive in the unremitting wind and the damp. In 1940, coastal life centered around subsistence fishing. Many families still used curraghs — traditional oared boats about 20 feet long, covered with tarred canvas. They gathered seaweed to fertilize their fields and sometimes, when vegetables were scarce, to eat. They also scavenged occasional flotsam and jetsam deposited by the unforgiving North Atlantic.

Scholars and students from all over the U.K. studied … the exceptional variety of seaweed drifting onto the Isle of Man’s shores.

By summer 1940, debris had been drifting ashore almost daily for months. It was the beginning of the Battle of the Atlantic; but German submariners called it Die Glückliche Zeit — “the happy time.” U-boats controlled the seas, attacking merchant and military vessels at will. Westerly currents brought the detritus of war to Ireland’s shores: pristine boxes of cigars and tobacco, automobile tires, brooms and brushes. Barrels of crude oil. An entire ship’s bridge. Empty lifeboats.

Then, the bodies began to arrive.

~~

On July 2, Margaret and a few other wives in Rushen Camp received devastating news: Their husbands had died when a German submarine sank a ship that was taking them to Newfoundland, Canada. One of the widows threw herself off a cliff soon afterward. Margaret later said that she had considered suicide, too. They hadn’t even been told their men were leaving the country.

~~

“Why do you care so much about what happened to my relatives?” came Yvonne’s question.

I thought of the stories Yvonne had heard as a child — about her mother Edith’s nightmarish experiences during World War II: of panicked evacuation from Belgium with her brother, into hiding in southern France; of Kurt’s capture, deportation, and death at Auschwitz; of Edith’s harrowing escape to Switzerland soon afterward.

And I thought about how, for my wife, Ernst Moser was just a name — the only grandfather she’d known was Margaret’s second husband, Walter Hansen. Yvonne’s question prompted some introspection: Why did her family’s story matter so much to me?

I have always been drawn to, moved by, stories of grief. My French mother, only 12 when she fled Paris with her Polish-born parents, also spent years hiding in southern France. Although they lost dozens of family members to Nazi slaughter, she didn’t burden me with those stories when I was young. But current research suggests trauma can change DNA. Perhaps I inherited my mother’s grief, and it resonates when it finds company.

~~

One afternoon in 2010, while searching for clues to Ernst Moser’s death, I discovered an online forum for U-boat history enthusiasts. I posted, “Does anyone know about a U-boat that sank a passenger ship during World War II?”

“Of course,” came the reply. “You’re talking about the Arandora Star.”

The SS Arandora Star in 1936 when it was still a luxury ocean liner. By mid-1940 the ship had been repurposed for the war effort. Photo: Heritage Images / Alamy.

On June 30, 51-year-old Ernst, with more than 1,600 other internees, military guards, and crew, boarded a ship bound for Newfoundland. Once, the Arandora Star had been a Blue Star luxury liner. Now, it was an overcrowded prisoner ship, painted battleship gray with no markings to indicate it carried civilians.

Guards draped barbed wire on the ship’s decks and gangways, trapping many internees below and limiting already-insufficient lifeboat access for everyone. The ship’s civilian captain protested the barricades to naval authorities. If their “floating death-trap” were to sink, he insisted, “we shall be drowned like rats.” He was overruled.

At dawn on July 2, a decorated U-boat commander ordered the launch of his last torpedo at an unmarked British ship 75 miles northwest of Ireland. The Arandora Star sank in less than 30 minutes. Ernst died at sea with more than 800 other men, including the captain and his crew.

~~

A month after the Arandora Star sank, Western People — a County Mayo weekly broadsheet — reported a body found on the Mullet Coast:

An elderly local resident with a vague wave of his hand indicated [to the reporter] the general direction of a small group of three or four men, including three priests, assembled on the shore … at their feet lay a figure.

Around the neck was a life-jacket, the black printed inscription on the canvas covering being ‘Star.’ Pathetically beneath the trouser legs and extending over the black shoes, hung the sock suspenders. Nobody knew the name or nationality of the drowned man.

Just then a little lad of ten or twelve years pulled my sleeve and said: “I found a stick with a name on it” … I was surprised to find the stick was a signboard of about a yard square bearing the words, printed in blue on a white background: “Arandora Star.”

Soon afterward, more corpses began washing onto Ireland’s shores. Many had no identification; internees’ papers had been confiscated upon boarding. Some names came to light through miscellaneous bits found in their pockets — a laundry receipt, a letter from a loved one.

Ernst’s body was never identified.

~~

Eventually, the ground gave way to rocky cliffs that dropped hundreds of feet to the sea, where roiling waves crashed over massive black boulders and tilted stone slabs.

I wasn’t sure what I would find on our visit to the Mullet Peninsula, or even what I was looking for. A 90-year-old witness? A clue to Ernst’s fate? Rationally, I knew there could be no answers. Yet I felt drawn to visit places where he might have washed up, and to better understand the people who might have found his body.

I’d read about the care with which western Irish residents had treated victims of the Battle of the Atlantic — tales of men risking their own lives to pull strangers’ bodies from the violent tides, of tearful prayers on rocky beaches, of impoverished communities paying for coffins and burying the dead in their cemeteries. I wondered what drove them.

I connected with Michael Kennedy, a historian at the Royal Irish Academy, and author of an essay titled “The Sinking of the Arandora Star.” An entertaining storyteller with a lilting baritone voice, Kennedy answered my innumerable questions over lunch at his family’s generations-old, creekside fishing lodge in Mayo. He also provided period newspaper articles about the tragedy, and a spreadsheet he’d compiled from government records of bodies recovered along Ireland’s Atlantic coast during World War II. It contained more than 350 entries, including dozens from along the furious coastline of the Mullet Peninsula.

Kennedy wrote to me that “the sinking of Arandora Star and the events of summer 1940 were, for communities along Ireland’s Atlantic seaboard, yet another harsh chapter in their generations-old relationship with an unforgiving ocean.” For them, traditional songs of sailors lost at sea were all too real. Many had lost husbands or sons to the North Atlantic. And in 1940, some still believed that, in Celtic tradition, the souls of men who drowned would find no rest unless their bodies were recovered and buried.

The people of West Ireland received little reimbursement for boat fuel, inquests, coffins, or burials. Yet they continued to treat the arriving dead as they would their own brothers:

The body which since last Tuesday had been wave-lashed in a cave at Erris Head, beneath a cliff some 200 feet high, was with great difficulty retrieved on Friday morning. [Two men] set out in a curragh, and entering the mouth of the cave in which the body was floating, their little craft was tossed backward and forward by the action of the swells, and several times disaster was narrowly averted. They succeeded in getting a rope around the floating body which was hauled to the top by a crowd of volunteers who had assembled at the scene.

Reading Western People’s many contemporaneous reports, I could only wonder if Ernst Moser had been found. He could have been that body recovered at Erris Head, or another pulled from a different cave a few miles south, described as about 50 years old, with a few English coins in his pocket.

Or he might have been one of the many who were never recovered. On August 10, 1940, Western People reported:

“About 100 bodies are floating in the sea off Inniskea Island. The sea is so rough that the bodies cannot be recovered. [They] are believed to be from the ‘Arandora Star.’”

Was Ernst’s body rescued, or was it lost forever to the deep? The question haunted me.

The turbulent coastline of Erris Head, County Mayo, Ireland. Photo: Nando Lardi / Alamy.

~~

Yvonne stood by a low stone wall overlooking the bay of Port Erin, chatting with a passing resident named David about why we were there. As Yvonne shared our story, I pulled up Margaret’s 1940 photo on my phone to show him. Then I looked up at the hills across the bay. Excitedly, I interrupted their conversation.

“Look at this photo! That’s the same hill!”

There were more houses than in 1940, but Yvonne was standing very near where Margaret had posed. I was stunned. This was no longer a history project. This was Margaret’s life made real.

David offered to help find Margaret’s addresses, and he texted the next morning: The Snaefell Hotel was gone; namesake apartments were under construction on the site. But he’d found Tower View — it was the “9th house on the right” on Ballafesson Road.

On our last morning on the Isle of Man, Wendy squeezed us and our luggage into her tiny Suzuki Alto and drove us back to Port Erin. The two-story house on Ballafesson Road had been updated, but it still bore a plaque engraved with “Tower View.” (The name referred to Milner’s Tower on a point at the bay’s northern edge.)

No one was home. We were disappointed, of course. But after 80 years, little would have been the same anyway.

So much of Port Erin was unchanged. We had walked the same beaches, inhaled the briny scent of the Irish Sea and marveled, as Margaret must have, at the innumerable varieties of seaweed on the Isle of Man’s shores, in shades of green, beige, white, red, and brown. Her time there had been filled with deprivation and terrible loss — but delivering her book into Wendy’s care felt like we were bringing it home.

~~

The Mullet Peninsula is dotted with cemeteries that overlook the Atlantic. At Faulmore, near its southern end, the oldest graves surround a ruined stone chapel on a low hill. In the newer section, at the edge of a sandy, boulder-strewn beach, lie unmarked graves with some of the Arandora Star’s dead. More are buried at Termoncarragh, surrounded by low stone walls on a high bluff, not far from Erris Head.

Rocks or crude wooden crosses were all that originally designated the graves I sought. They were replaced after the war with engraved gray headstones. I bent down to read one of the epitaphs near Termoncarragh’s outer wall: “A sailor of the 1939-1945 war/ Found 15th September 1940/ Known unto God.”

Nearby, a large, smiling, bespectacled man rode a commercial-grade lawn mower. He told me he volunteered there with six other men, removing dead flowers, trimming the grass, and repairing stone walls.

“Why do you do it?” I asked.

“Because it’s the right thing to do.”

~~

So many nations did the wrong thing. Britain hampered the Mosers’ efforts to gather their children and leave for America, then accused them of Nazi loyalties. The United States, driven by isolationism and antisemitism, refused to accept most Jewish refugees. Few countries were more welcoming (although in an absolute sense, the U.S. did accept more refugees than any other country).

In 1939, U.S. quotas limited immigration of German and Austrian nationals to 27,370. More than 300,000 people had applied.

It’s a story that repeats whenever war, catastrophe, or tyranny displaces people of “foreign” backgrounds from faraway places: Too often, governments acknowledge the plight of refugees but expect others to address the problem.

Ernst and Margaret fled a country that hated them for another that feared them. The official inquest into the Arandora Star’s sinking concluded that all German nationals on board were “dangerous characters” vetted by the tribunals. Those who died have mostly been forgotten — remaining only as names on a list in the British National Archives.

~~

I walked on a trail around the edges of Erris Head. The rain had stopped, though the wind had not, and sunshine, warm and glorious, burst through. Seabirds called out and wheeled in the sky. Sun and wind-blown clouds passed over the wet, short-cropped grass — a movement of light and shadow that mirrored the writhing of the sea below.

Why do you care so much about what happened to my relatives?

Perhaps telling Ernst’s story is a way of finally laying him to rest. I hope so.

I peered over the edge of the world at three enormous sea caves carved into the cliffs below me. I tried to imagine a body floating there, men hauling on ropes in the biting wind and rain while others risked death on the rocks and surf below, trying to go where a curragh shouldn’t, risking their lives to do what was right for someone they never knew.

Mike Bernhardt

Mike Bernhardt is an eclectic writer who loves the water, be it diving coral reefs in Indonesia, swimming with sea lions in the Galápagos, or researching drowned ancestors off the coast of Ireland.