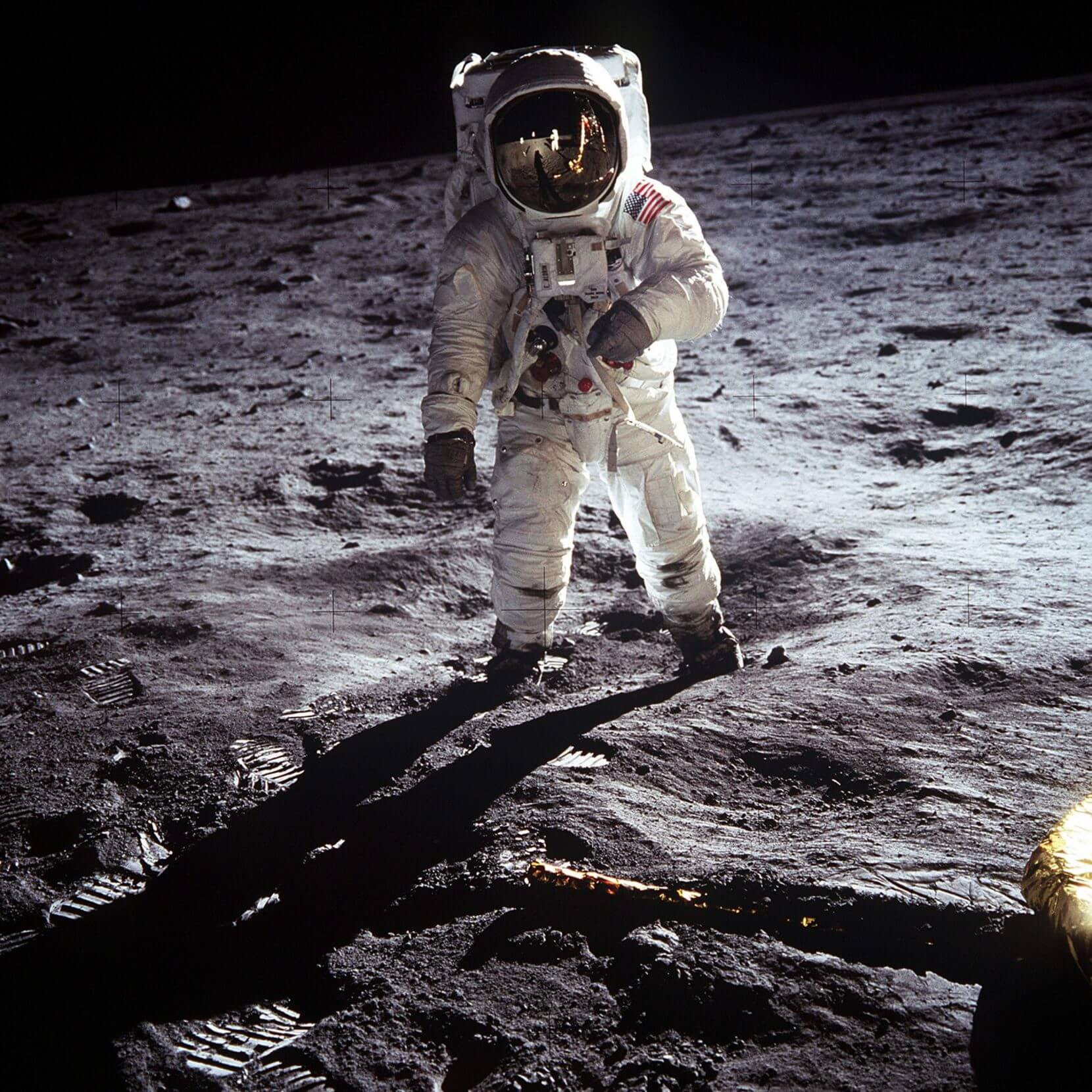

Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin on the surface of the moon, with Neil Armstrong reflected in his visor. On July 20, 1969, the two men became the first humans to walk on the moon. PHOTO: COURTESY OF NASA.

It’s 1:40 p.m. on July 18th, and the video transmission we’re receiving has traveled 200,000 miles to get to us. We’ve been building to this moment for years and we’re expecting the transmission, but it’s early. NASA Mission Control Center in Houston isn’t ready for it.

“Apollo 11… We’re not quite configured here at Houston for the transmission. We’ll be up in a couple of minutes. Over.”

The voice of Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin crackles through from the command module: “Rog[er.]”

Within the hour, Aldrin will complete the first space inspection of the lunar module Eagle, the craft he’s about to pilot to the moon. Commander Neil Armstrong will be with him. Command Module Pilot Michael Collins, the third member of the Apollo 11 crew, will be joking about TV stagehands not knowing where to stand during the broadcast. What is about to happen in space over the next two days is incredible — something many of us thought was impossible less than a decade ago. But something just as incredible is happening here on Earth.

At 3:09 p.m., Armstrong will look out a window. He’ll see the orb of the Earth before him. “We have a very good view of it today,” he’ll say, “There are a few more cloud bands on than yesterday when we beamed down to you, but it’s a beautiful sight.”

Here on this fragile and beautiful sphere that Armstrong can see from space, we are stopping in our collective tracks. Hundreds of millions of us are turning away from our individual lives to marvel at the collective accomplishment of our species.

By 10 p.m. tonight, the velocity of Aldrin, Armstrong, and Collins will slow from their initial lunar trajectory velocity by a factor of 10. Then, at 10:11:55 p.m., they will cross the equigravisphere — the point at which the gravitational pull of the moon will become stronger than the pull of the planet watching them. In less than 48 hours, two of these men will go where no human has gone before. But this is not a story about what those men will give to humanity. This is a story of what humanity has given these men. Armstrong can feel us up there with him, which is why one man’s first stride onto the lunar surface will be more than his step — it will be our collective leap.

This moment is no longer before us; it happened half a century ago. Today, we are not gathered here on Earth in rapt anticipation of what humankind is about to accomplish.

But we should be.

~~

Buzz Aldrin wasn’t the only buzz in the air in July 1969. At newsstands across the United States, the grinning face of Neil Armstrong gazed at passersby. From the cover of Newsweek, he stood in his pristine white spacesuit, posed in front of a picture of the moon, helmet in hand, with blue eyes that almost matched the NASA insignia on his chest. On the cover of Life he waved as he prepared to board Apollo 11, his 5’11”-, 165-pound-frame striding confidently in his bulky spacesuit. The headline read “Leaving for the Moon.” As the commander of the mission, he was alone in many images, but not in all of them. In some, he posed alongside a determined looking Michael Collins and a slightly mischievous-looking Buzz Aldrin whose smile was a bit of a smirk.

Portrait of the prime crew of the Apollo 11 lunar landing mission. From left to right: Commander, Neil A. Armstrong, Command Module Pilot, Michael Collins, and Lunar Module Pilot, Edwin E. Aldrin Jr. PHOTO: COURTESY OF NASA.

When Apollo 11 launched, people around the world gathered in front of televisions wherever they could find them. Some one million spectators clogged the roadways and beaches around Kennedy Space Center. Roughly half of Congress traveled to Florida to watch the launch live, and the event was covered in person by more than three thousand reporters from 56 countries. When Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took the first steps on the moon, an estimated 600 million people — 16% of the world’s population — watched live.

We were more than a decade into the Space Age. It had been twelve years since the Soviet-launched Sputnik 1 became the first artificial earth satellite and the catalyst for an age of competition, exploration, and wonder. By this time astronauts had become icons. They were pilots and engineers, military officers and university professors. They drove their Corvettes too fast, re-engineered each other’s vehicles as practical jokes, and had their faces plastered on newspapers everywhere. Their names — Glenn, Schirra, Grissom, Lovell, Aldrin, Armstrong, and even Gagarin — rolled off tongues as if these men were our old friends. They had swagger, smarts, and celebrity. They were icons of a different sort than we know now.

New York City welcomes the Apollo 11 crew upon their return from the moon with a ticker tape parade down Broadway and Park Avenue. PHOTO: COURTESY OF NASA.

~~

The things that the men and women of the Space Age accomplished were unprecedented, crazy, even. But there was nothing unique about this undisguised audacity and the excited masses who encouraged it. Throughout the centuries, intellectual icons and explorers have repeatedly set forth into the unknown, and come home to thrilled and reverent crowds.

Albert Einstein, with his wild hair, thick mustache and quirky smile, is an obvious example: world famous, instantly recognizable, his name synonymous with genius. What could be more audacious than challenging our very understanding of the universe, following mathematics into uncharted realms? The outcome of such a journey was revolutionary. But the power of Einstein’s following was nearly as striking as the power of his findings: Even now, more than half a century after Einstein left us, people who have never balanced an equation quote his.

During his lifetime, Einstein toured like a rock star — people mobbed lecture halls to see him, trampling each other to get inside. He was in the newspapers so often that he quipped, “The reader gets the impression that every five minutes there is a revolution in science.” A technical article he wrote on his unfinished and untested unified field theory sold out in three days. As he neared the end of his life, he chose to be cremated because he was afraid that people would come “to worship at the altar of [his] bones.” A legitimate fear, it seemed, as when he died, the pathologist on call stole Einstein’s brain, which scientists around the world later sliced and studied to find the source of his genius.

Today, we are not gathered here on Earth in rapt anticipation of what humankind is about to accomplish. But we should be.

But even Einstein wasn’t unique in his following. Thomas Edison, the man who harnessed both sound and light, was also a magnet for crowds and publicity. The first floor of his laboratory was constantly filled with visitors curious to see his inventions, and investors looking to fund his research. His lab was dubbed the “Invention Factory,” and Edison, “The Wizard of Menlo Park.” A part of Edison was also taken from his deathbed, though it was more ethereal than a brain: His last breath was captured and secured in a test tube, then put on display at a museum. Following his death, people around the globe dimmed their lights in his honor.

Humanity has celebrated discoveries not just at the frontiers of science, but at the frontiers of the world as we knew it. At the turn of the 20th century, as polar exploration gripped the globe, men like Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott, and Ernest Shackleton, came into the limelight. During a series of three Antarctic expeditions, Shackleton risked life and limb in one of the world’s harshest and littlest-known environments — at one point venturing further south than anyone before him, only to nearly starve to death on the way back to his ship. The Royal Geographical Society awarded Shackleton a Gold Medal, King Edward VII made him Commander of the Royal Victorian Order and later knighted him. When Shackleton announced a Trans-Antarctic expedition, he was showered with more than 5,000 applications from the public to join it and picked up a stowaway who hid in a locker for weeks. As he set out on his final expedition, Shackleton offered the service of his ship and crew to the English forces preparing for WWI, in case they believed that protecting the homeland was more important than exploring a foreign one. But Shackleton’s expedition was considered crucial, and he received a single-word wire from the Admiralty: “Proceed.”

These men were exceptional, but so was the excitement around them. In the 19th and 20th centuries, these scientists, inventors and explorers set out to make discoveries at the frontiers of human knowledge — and we cheered them on, just as 50 years ago, we cheered on Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Mike Collins.

~~

We want to cheer like that again. We want truly audacious feats of human ingenuity to be celebrated deeply — and we have a lot to celebrate. We live in a time when we are making significant breakthroughs in genetics and medicine; when deep-sea exploration and monitoring for extraterrestrial signals have achieved a scope never seen before. The opportunity to celebrate women and people of color behind such ventures is unprecedented.

In the 19th century, Edison harnessed light and sound. At the turn of the 21st, we harnessed information. The Internet is one of the most audacious inventions of our time, but how many of us can name the minds who contributed to its creation? Who can name the British computer scientist — knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for his work — who first proposed we share information through a technology he called hypertext, and created the world’s first web page? (Timothy Berners-Lee, anyone?) What about the woman who pioneered a tool that spurred a revolution in genetics? (Jennifer Doudna!) Will she need to be buried in a secret location to prevent the masses from worshipping her bones?

The two of us were born in the 1980s: late enough to have missed the golden age of the Space Race, but early enough to understand the feeling it conjured. We both grew up in coastal California — one of us a stone’s throw from an air force base that was, at one time, scheduled to become a shuttle launch site. We pretended to be astronauts during simulations at space camp, launched rockets in our backyards, and watched scientists sketch rocket schematics on napkins at fast food restaurants. We were just kids, but we got a glimpse of the celebration of collective human endeavor.

We want it back. We want to live in a world where the names of astronauts, explorers, scientists and inventors roll off our tongues as easily as the names of the Kardashians.

We’re willing to bet that we’re not alone.

~~

The time for passive media consumption is over.

True exploration — expedition-based travel — cannot thrive without a thunderous cultural demand for it.

The two of us were drawn to our work by humanity’s legacy of exploration. Travel journalism, at its best, gives the world a glimpse of frontiers — not just in geography, but in science, culture, and art. These frontiers aren’t covered as much as they used to be, but they remain the birthplaces of discovery — so we created Hidden Compass to showcase them.

We want truly audacious feats of human ingenuity to be celebrated deeply — and we have a lot to celebrate.

But now it is time for us to throw our hat over the wall, because for Hidden Compass to truly celebrate exploration, we cannot be just a magazine. We must be a movement.

And that means that our audience can no longer just be an audience.

Over the next year, our audience will transform into an alliance — an alliance that will work to create a world where scientists, explorers, artists and inventors are celebrated. We’re going to bring back the era of intellectual icons.

This means that you’ll see us asking you to engage with us in a way that you’re probably not used to engaging with media. We won’t expect you to merely consume what we publish. We will invite you to participate in Hidden Compass’ production — to engage with writers, artists, and photographers, and, eventually, to join a collective to launch the expeditions of explorers and scientists.

If this idea excites you: then share it. A movement requires people and you will be our most important recruiters. There are a lot of changes coming. Some will happen behind the scenes as we build the infrastructure to support our new mission. Some will be bold and sudden as we launch new projects. And many will be gradual as we build upon the foundation we’ve been laying for the last two years. We will be keeping you updated through our social media channels and our newsletter. (Sign up to follow us if you haven’t already.) From time to time, you’ll even see the two of us front and center, chatting with you about our plans. In fact, tomorrow, we’ll be live on Facebook at 1:00 p.m. PDT.

In the meantime, let curiosity be your guide. This weekend, we celebrate the anniversary of one of humankind’s greatest endeavors. Take in the coverage. Listen to the words spoken fifty years ago and those spoken in the years since. Look at the images of mothers clutching their children to them, of speechless, teary-eyed news anchors, and of embracing strangers gathered in front of television shops and in town squares around the world, their eyes all glued to screens because their species was about to do the impossible. And then think about what it might be like to feel that again, because we can.

If this all seems a little crazy, well, perhaps it is. But audacity has always been the key to making the impossible, reality — to making the unattainable, undeniable. Once upon a time, creating light in a bulb and reaching the South Pole seemed crazy. So did traveling down the street in a horseless carriage, or reading this story on a computer or phone. Once upon a time, strapping three men to a rocket and launching them across 240,000 miles of cold, vast space was crazy, too. It was crazy enough to make humanity stop and wonder what else might be possible. By comparison, we can only hope our mission is crazy enough.

View of the Earth from Apollo 11. PHOTO: COURTESY OF NASA.

Hidden Compass

Hidden Compass is an award-winning, women-led media company that’s forging an Alliance to turn storytellers and explorers into heroes and champion a new age of discovery. Learn more by clicking “about” in the navigation bar.

Never miss a story

Subscribe for new issue alerts.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive updates from Hidden Compass regarding new issues and other ongoing promotions such as workshop opportunities. Please refer to our Privacy Policy for more information.