Support Hidden Compass

We stand for journalism, science, history, and hope. Make a contribution to Hidden Compass and stand with us.

This story has been republished in the Hidden Compass Legacy Issue in celebration of reaching 100,000 readers. All proceeds from this campaign will support Hidden Compass.

There were flies in its fur — not many, just enough to remind me that even up here in this harsh environment, nature cleans up after itself. I got on my knees and looked closely at the bear. It was young. Not a cub, but not fully grown either. It was June, but the cool temperatures meant decay was slow to set in. Still, the bear’s fur was patchy in some spots, its eyes gone — likely taken by scavenging birds.

I moved around to get a better look at its enormous paws, claws still intact, and then came back to its head. Lying down on my stomach, I got face to face with the bear.

“It is not a happy thing, but it is part of the story,” said Ole Jørgen Liodden, our rifle-toting Norwegian guide, photographer, and polar bear researcher.

This was certainly part of the story, but what exactly was the story?

A dead polar bear on the shore of an island in Svalbard, Norway. The remote archipelago is home to one of 19 distinct populations of wild polar bears. Photo: Sivani Babu

~~

The Ket of Siberia called them gyp — grandfather. To the Inuit, they are nanuk — an animal worthy of great respect. And to the Sami of Northern Europe they were ísavoî — sacred. Ursus maritimus, the farmer, ice bear, sailor of the floe, the old man in the fur cloak. Whatever the name, polar bears have captivated us for centuries: We have mythologized them, revered them, feared them, and hunted them. And now we wonder if we can save them.

A polar bear wanders near the face of a glacier. This is prime hunting ground for these intelligent predators. Photo: Sivani Babu

~~

Well above the Arctic circle, Svalbard is wild and remote — a stark, 24,000-square-mile Norwegian archipelago carved over millennia by the undeniable force of ice. These fjords are home to only the heartiest of animals — flitting arctic terns that migrate 44,000 miles roundtrip between the Arctic and the Antarctic; mustachioed, long-tusked walruses that can stay awake for more than three days straight while at sea; formidable polar bears that can smell their prey from a kilometer away and sense movement in water below a meter of compacted snow. And of the archipelago’s estimated 2,667 human residents, roughly 2,100 of them live in Longyearbyen — a 94-square-mile outpost of a town. In short, this is not the sort of place one ends up on a whim, except, of course, when one does exactly that.

Wild and remote, the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard is an Arctic landscape of rugged fjords and sea ice. According to NASA, the sea ice has been decreasing by roughly 13% per decade. Photo: Sivani Babu

I hadn’t planned on traveling to Svalbard. During a summer photography trip, I found myself in Lofoten, Norway, getting ready to travel on to Scotland. I was unprepared for travel in the Arctic: I’d brought only a lightweight pair of non-snow-worthy hiking shoes and nothing warmer than a thin down sweater.

We have mythologized them, revered them, feared them, and hunted them. And now we wonder if we can save them.

But there was an unexpected opening on a photography excursion to Svalbard, where I might get the chance to see polar bears in the wild. The trip began in less than 48 hours.

I didn’t hesitate.

~~

Even from a distance, the face of the glacier towered over the landscape, a wall of ice in soft shades of blue and aqua rising from the earth. Our pilot silenced the Zodiac’s motor and we drifted through the dark water, a stillness about us as we tracked a whitish speck on the horizon.

As we drifted closer, the speck grew larger and began walking toward the glacier, slowly, with a characteristic pigeon-toed gait that had once earned its ancestors the nickname “the Farmer.” As it moved, a seal in its path made a hasty exit, slipping down a breathing hole in the ice and escaping to the water below.

A polar bear and seal near the face of a glacier in Svalbard. The seal didn’t stick around long, escaping through a breathing hole in the ice. Polar bears rely on the ice for hunting, often lying in wait for seals near breathing holes. Photo: Sivani Babu

I watched, mesmerized, as the large and mysterious animal turned toward us, its behemoth body blending into the snow and ice that surrounded it.

Can an animal singularly define a place?

Yes, it can: Arctic. From the Greek arktos, meaning “bear.”

~~

The life of a polar bear has never been easy. Nothing in the Arctic is easy. It is a brutal and desolate existence.

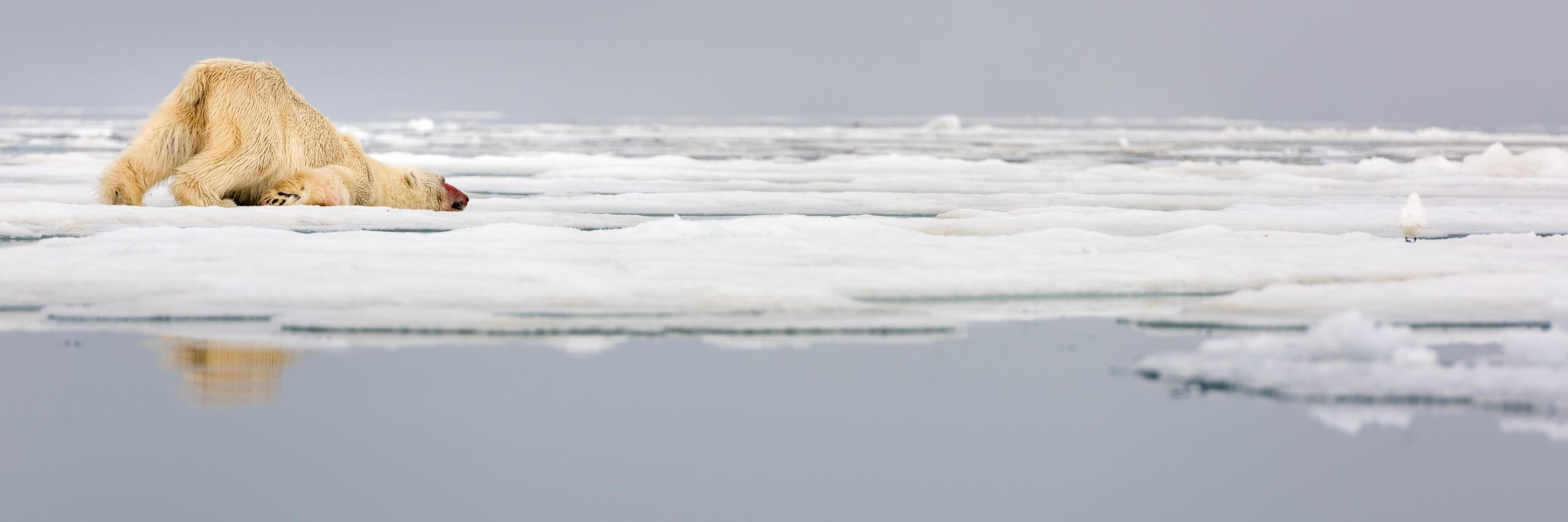

On an ice floe, a polar bear feeds on a seal. Life in the Arctic is brutal and desolate. Photo: Sivani Babu

But the challenges faced by polar bears and the threats to their survival have been different depending on the decade in which they lived.

For many years, the single greatest threat to polar bears was hunting. The Inuit and other native peoples had hunted the animal for generations, eating the meat and using the skin and fur for shoes and clothing. Eventually, though, the rest of the Western world joined in, and for nearly 400 years, trophy hunters, fur trappers, sealers, and whalers harvested polar bears by the hundreds and thousands. In Svalbard, which is home to only a small percentage of the global polar bear population, more than 30,000 polar bears were hunted between 1871 and 1973. In a couple of those years, nearly 1,000 bears were taken, and only twice during that 102-year span were fewer than 10 bears killed in a single year: in 1942 and 1943, at the height of World War II, when humans were consumed with killing each other.

Did we hunt polar bears to the brink of extinction? Possibly. There is no scientifically credible estimate of how many polar bears were left when commercial hunting ceased in 1973. None of that really mattered to the dead bear on the beach, though. It hadn’t died at the hands of a hunter.

Ole stepped in to take a closer look at the bear’s head.

“Is there any way to know how he died?” I asked.

~~

In the years following the commercial hunting ban, the global population of polar bears has increased, as has our capability of studying them. With the aid of thermal and radar technology, scientists now estimate that there are between 22,000 and 31,000 polar bears in the wild.

But where one threat has partially subsided, another has begun to fill the void.

In recent years, polar bears have become the poster child for the impact of climate change. When National Geographic published a video of an emaciated bear in 2017, it went viral, intensifying our already deep concern for the future of the species. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) suggests a 30% decrease in the global population of polar bears is likely by 2050.

Where one threat has partially subsided, another has begun to fill the void.

But some predict that within a similar time frame, they’ll go extinct.

~~

In Svalbard, we were fortunate to encounter several polar bears. The day after we saw our pigeon-toed “Glacier Bear,” we came across another one napping on the ice, his clean coat shining in the sun.

“I get that he’s a ferocious apex predator that would gladly make a snack out of me, but I kind of want to hug him,” I said.

A polar bear naps on an ice floe. Photo: Sivani Babu

Later, we made our way to a pair of male bears feasting on a fresh seal.

Photo: Sivani Babu

Their faces were bloody as they filled their bellies, prioritizing the high-calorie blubber before moving to other parts of the seal. All around them, opportunistic birds waited, swooping in and stealing bits of meat when they could. We watched the bears in the silvery light of the fog until the ice began shifting, signaling it was time to return to the ship.

Opportunistic birds wait to grab stray pieces of meat as a polar bear dines on a seal. Photo: Sivani Babu

On an ice floe in Svalbard, a polar bear walks away from the kill with a piece of seal hanging from his mouth. Photo: Sivani Babu

With a belly full of seal meat, a polar bear cleans the blood from his chest by scooting along the ice. Photo: Sivani Babu

Every living bear we encountered appeared large and healthy. They were a far cry from the emaciated bear in that viral video. But what did that mean? The piece of the puzzle that is often missed is just how little we know about polar bear ecology. There are 19 specific subpopulations of polar bears. In 2017, the World Wildlife Fund for Nature, using data from IUCN’s Polar Bear Specialist Group, determined that of those 19 populations one was in decline, two were increasing, and seven were stable, but nine distinct populations are listed as “data deficient,” including the Barents Sea population of which the Svalbard bears are a part. In other words, we don’t know what is happening with those subpopulations, which means we can’t know how climate change has impacted the polar bear population as a whole.

What we do know is that as a result of climate change, the Arctic sea ice is thinning and decreasing. And as that loss continues, added stress will be placed on the bears. Of all the names given to polar bears, perhaps the most accurate is “ice bear.” They hunt, they sleep, and they rear their young on the ice. Decreasing sea ice is habitat loss. So will polar bears starve and drown in droves? Will they be unable to successfully raise their young? Will they become extinct?

Or will they adapt? And if they do adapt, what might that look like? Those are just some of the questions that polar bear researchers, including Ole, are trying to answer.

Ole’s ambitious Polar Bears & Humans project aims to fill crucial gaps in polar bear research by taking a more comprehensive view. Yes, looking at the effects of disappearing sea ice is critical, argues Ole, but so is the sustainability of current hunting, the extent of poaching, the adaptability of bears, the choices they make in response to changes in their environment, the effects of increased human-bear interaction, and the impact and accuracy of our current methods of study. Each of those needs to be understood with regard to each subpopulation for us to understand what lies ahead for the ice bear.

~~

But what about the bear on the beach in Svalbard? Ole ruled out a few possibilities:

“Sometimes, if they get desperate for food, they behave crazy. A young bear might attack a walrus … but if he was killed by a walrus, we should see evidence.”

There were no obvious signs of trauma — no visible deformities, no tusk-sized holes, nothing that suggested a fight to the death with a creature weighing more than 2,000 pounds.

What else?

“Sometimes, they drown.”

But a bear that had drowned and washed ashore would probably look worse than this.

“It doesn’t look like it starved.”

It didn’t.

There are no conclusions to be drawn from the death of a single polar bear. We just didn’t know enough. As unsatisfying as that was to admit, it was the truth.

~~

I stood at the bow of our ship, looking out over the sea ice stretching for miles like delicate lace over indigo water.

“There’s a bear heading our way,” someone said.

I borrowed a pair of binoculars and scanned the ice, spotting the bear off of our port side. As he came closer, I could see the water droplets cascading from his hind paws with each step. A reverent silence fell over us as it had and as it would with every sighting. The bear passed just in front of our ship, with our eyes fixed upon him as he walked across the ocean’s surface.

What challenges had he faced to get here? How many times had he flirted with death and narrowly avoided becoming a body on the beach with sand and dirt and flies in his fur? And most importantly: Where was he headed? Where was his species headed?

Polar bears embody the Arctic. They are of the ice — built to thrive in desolation. But the Arctic is changing and these magnificent beasts must either change with it, or risk disappearing forever. What, I wondered, will the next 100 years bring?

I cast my eyes on the vanishing figure in the distance, catching the last glint of sunlight on his fur as he dove into the water, and disappeared.

A polar bear walks across the thinning sea ice in Svalbard, Norway. Where is he headed and what will the next 100 years bring for his species? Photo: Sivani Babu

###

As of May 2023, polar bears remain vulnerable. Though we have better data, we still lack robust estimates of polar bear populations. What we do know: Sea ice continues to decrease, increasing stress on a wide variety of magnificent creatures large and small, including the ice bear.

Sivani Babu

Sivani Babu is the co-founder, co-CEO, and creative director of Hidden Compass. By merging journalism, art, and exploration, she tells stories that offer perspective, context, and an awe-inspiring sense of scale to the human experience.

Never miss a story

Subscribe for new issue alerts.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive updates from Hidden Compass regarding new issues and other ongoing promotions such as workshop opportunities. Please refer to our Privacy Policy for more information.