Support Hidden Compass

We stand for journalism, science, history, and hope. Make a contribution to Hidden Compass and stand with us.

A

dog perches at the prow of a small boat. Mist hangs over the water. Its ears flick first in one direction and then another in an attempt to map the soundscape of this alien environment. The year could be 1,500 B.C.E., 8,000 B.C.E., or earlier still. Though the framework is but a hazy conjecture by archaeologists — and the details a matter of poetic license — this ancient scene is easy enough to picture, thanks to our enduring affinity for dogs.

In other boats in this hypothesized flotilla, more dogs crouch, slinking between supplies or pressing against their humans amid this sudden unmooring from their home in mainland southeast Asia. A seabird screams; an infant wails. From the dogs rises a mournful song.

The humans, tense about their tenuous journey, bark crossly. Singing gives way to silence once more. Days later, land appears. These are the islands of present-day Indonesia or possibly New Guinea. The archaeological evidence is inconclusive. Other accounts say the dogs may have come here by way of ancient land bridges.

Upon arrival, some dogs stay close to their people. Others slip off into the forests, perhaps in the hopes of never seeing the ocean, or a human, again.

Thousands of years later, that divide persists. Some descendants of those ancient creatures curl up at the feet of doting humans across the globe. But for the wildest of these singing dogs, the mist became their refuge. It’s there, immersed in the fog, where researchers hope to solve one of the animal kingdom’s greatest mysteries.

~~

Here’s what is thought to be true: Dogs migrated out of southeast Asia and into New Guinea between 5,500 and 20,000 years ago. This expansive time span illustrates exactly how little we know about canine evolution. It is actually possible that the wolf and the dog evolved from a common ancestor. That is to say, dogs may not have evolved from wolves as we know them. Rather, the modern wolf and dog may have originated from an unknown species of wild canid, whether an extinct wolf or another creature.

The wild dogs of this South Pacific island, known as New Guinea highland wild dogs, are thought to be the most primitive canines still alive. They likely represent something between this ancestor and what we now consider domestic dogs.

Establishing this connection, however, requires cooperation from a creature that’s known best for its enigmatic qualities. No scientist had ever gotten close enough to try.

The mist became their refuge.

~~

At the end of the second millennium C.E., a slender, pale-skinned man from halfway around the planet struggles up a narrow mountain path on the island of New Guinea, an incongruous landscape where steamy, tropical lowlands give way to rare equatorial glaciers.

A helicopter approaches the precipitous slopes of Puncak Jaya — the highest peak of Oceania at 16,024 feet. Also known as Carstenz Pyramid for the Dutch navigator who surveyed the summit in the 17th century, the peak became known as Puncak Jaya, or Victory Peak, when Indonesia declared West Papua’s independence from the Netherlands in the 1960s. Photo: Jez O’Hare.

His boots searching for purchase on the rain-slicked rocks, he is alert to every movement, every sound that punctuates the eerie silence. The squawks of birds-of-paradise reverberate across the chasms separating the peaks, and then all is quiet. Cocking an ear, he listens for other sounds — whines and howls.

Improbably, the man is looking for the wild progeny of those primitive dogs on the boats.

He is James “Mac” McIntyre, a biology teacher and track coach turned independent researcher. He has made it his personal mission to track these rare, wild dogs and assess their place in the canine family tree. When he began his quest here in the 1990s, the last official sighting had occurred in the 1970s. Most researchers had given up on the wild dog, assuming they had gone extinct in their native habitat, a cordillera surmounted by Puncak Jaya — the world’s highest island summit.

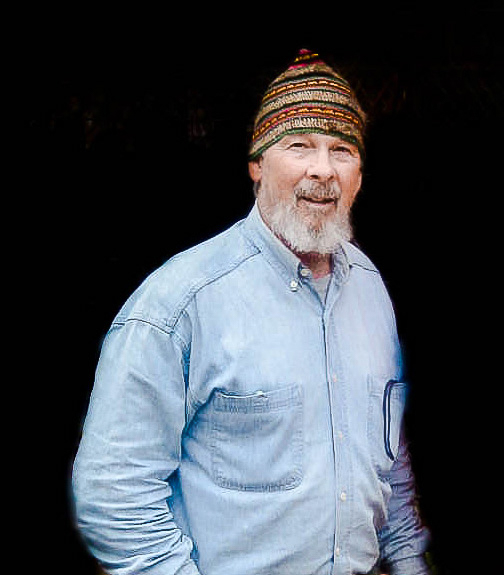

Researcher James McIntyre has been tracking New Guinea highland wild dogs since the 1990s. Photo: Courtesy James McIntyre.

McIntyre’s work entails climbing crags nearly as precipitous, in a frigid drizzle no less. “Every day we’re chilled to the bone, soaking wet,” recounts McIntyre from the comfort of his home on Florida’s Amelia Island.

But the rough conditions only seem to fuel his enthusiasm. When speaking about his quarry, Mac’s grizzled features brighten in youthful delight. Like a latter-day mountain man, descended from the peaks to relay the wonders he’s seen to the civilized world, he’s as sly and wily as the dogs he tracks.

McIntyre first got drawn into the saga of the highland wild dog while working at a private breeding center for endangered species. He spent his days surrounded by pens of imperiled creatures, a terrestrial ark brimming with rhinos, okapi, zebras, cheetahs, gazelles, and maned wolves.

Ecologist I. Lehr Brisbin approached him with a strange proposal. Having heard that McIntyre was planning an expedition to the island of Vanuatu to investigate a population of intersexual pigs, Brisbin offered to help fund a trip extension to Papua New Guinea, to seek out New Guinea highland wild dogs. Nearing retirement, Brisbin was concerned by the waning interest in, as well as the hybridization of, this unique animal, which had been dismissed as a mere feral dog — nothing special in a taxonomic sense.

Imagine having a coelacanth — that bizarre “living fossil” from the dinosaur age that still lurks deep in the sea — and being told that it was merely a slightly unusual goldfish.

Wraithlike, they seem to evade capture by even a remotely triggered lens.

In 1996, McIntyre arrived in Papua New Guinea, catching a one-way helicopter flight to a primitive research facility perched in a mossy cloud forest atop Mount Stolle. After four weeks on the dog’s trail, Mac hiked down from the mountain. He hadn’t laid eyes on the dog, but — buoyed by a few tantalizing indications that the species was still out there, including an unmistakable howl — the thrill of the hunt had seeped into his pores.

New Guinea highland wild dogs were out there in the mists, eluding observation, clearly independent of humans. These weren’t just goldfish gone wild. They were coelacanths.

~~

Whether they arrived with people or on their own, highland wild dogs melted into the mountainous terrain of New Guinea and for millennia were known only to native peoples, some of whom revered the creatures as godlike. While some native groups occasionally captured them for use as hunting companions or killed them and mounted their skulls as status symbols, the dogs persisted as truly wild animals, adapting to the arduous conditions of the island’s alpine ecosystem with aplomb.

New Guinea highland wild dogs have spent decades evading researchers amid the mists of the Puncak Jaya region, ringed by jungle and ridged with rare equatorial glaciers. Photo: Jez O’Hare.

The island’s largest land predator, they developed uniquely flexible paws that allow them to climb trees — a necessary adaptation in an environment where many of the juiciest prey, such as fuzzy tree kangaroos and possums, have taken to an arboreal existence.

Like Rin Tin Tin’s tow-headed country cousins, they resemble any number of primitive canines: the pariah dogs of India, the Carolina dogs of North America, even domestic breeds like the Shiba Inu. They also look a little like the dingo of neighboring Australia, where their golden fur is a more appropriate match for the landscape, but are shorter and feature wider skulls. This similarity, it comes to pass, is not a coincidence.

~~

Hunched under a poncho, McIntyre fiddles with a recorder as raindrops land on him like liquid ball bearings. Two decades after his first foray into New Guinea highland wild dog territory, he’s back, this time to Indonesian West Papua. He’s after definitive proof.

A shrill note emerges from the device, followed by yapping and a sustained yowl. These are not the sounds of the New Guinea highland wild dog, with none of that mellifluous, aquatic quality that gives this canine its other name: the singing dog. Rather, McIntyre is blasting the calls of the North American coyote into the fog in the hopes that the novel sounds will evoke a response.

McIntyre wants photographs, but luring these dogs toward a camera is no easy task. Wraithlike, they seem to evade capture even by a remotely triggered lens.

“I had my first dog walk by the camera. I got a picture of his ass end and that was it,” he gripes.

A trail camera, erroneously set to 2014, caught only the backside of a New Guinea highland wild dog during a 2016 expedition. Photo: Courtesy New Guinea Highland Wild Dog Foundation.

But Mac has some putrid tricks up his sleeves. As distinct as New Guinea highland dogs are, there are some canine universals. All dogs love things that stink. Crouched in the rain, he smears a variety of odiferous compounds around his cameras — castoreum, coyote urine, skunk juice.

“We had them there for a half hour,” he recalls, laughing.

For Mac, this marks victory. Twelve trail cameras net 149 photos of the dogs.

“I’ve gotta tell you,” he says, “I squealed.”

The photos provide conclusive visual proof — the first in decades — of the dogs’ persistence in the wild.

During a 2016 expedition, a trail camera (erroneously set to 2014) captured New Guinea highland wild dogs in West Papua, after being lured to the scene by McIntyre. Photo: Courtesy New Guinea Highland Wild Dog Foundation.

~~

Imagine the Sydney Harbor. Boats blow their horns; the noisy conversations of silver gulls echo over the water; waves lap gently against the rocks. Then a pair of mournful wails emanate from a nearby cliff.

Two New Guinea singing dogs now live at the Taronga Zoo. Thousands of miles from their native slopes, the dogs still call as if their relatives might be just over the next rise.

Identified by Western science in 1897, following their discovery on a Papua New Guinea peak, New Guinea highland wild dogs were first brought into captivity in 1956. These specimens were classified as their own species, Canis hallstromi. Eventually they were distributed to zoos across Europe and North America, where the creatures came to be known as singing dogs due to their liquid yodeling.

Later studies in the 20th century led many canine specialists to believe that the species was less significant. They were interpreted as feral dogs, at best a subspecies of our beloved Canis familiaris.

As a result, many zoos divested themselves of their singing dogs. Some ended up in private homes as pets. But no amount of domesticity could tame their inherited impulses — nor silence their song.

~~

A helicopter deposits McIntyre and his small crew atop a remote peak in West Papua, with only a small mining operation nearby. Two years have passed since his photographic feat. Again, he announces their presence by broadcasting coyote howls.

An eerie liquid yodeling seems to come from nowhere and everywhere at once — as if the mists themselves are chorusing. Return howls are one thing. But McIntyre is after a tangible piece of the dogs — blood samples — for a thorough DNA analysis.

Like a latter-day mountain man, descended from the peaks to relay the wonders he’s seen to the civilized world, [James McIntyre] is as sly and wily as the dogs he tracks.

Metal clangs and curses fly as the team positions their traps in the ever-present rain. They place clots of cooked chicken inside the traps — an irresistible treat to an animal used to gamey local poultry. The dogs take the bait.

Wrangling the creatures is a challenge. The first one manages to escape by pulling the door inward and squirming through the gap. At one point, McIntyre has to crawl into the trap and bodily restrain a struggling canine. By pressing him briefly against the mesh, he allows his teammate, an Indonesian veterinarian, to plunge a syringe of anesthetic into the dog’s flank. Ultimately the team manages to trap a pair of dogs and immobilize them temporarily, which allows them to examine the dogs and collect an array of their DNA — hair, saliva, skin tissue, and syringes of blood.

“Within 20 minutes we were done no matter what,” he says. “We reversed them and put them back in the cage until we saw that they were totally alert. We didn’t want them to walk off a cliff.”

~~

In New York City, a leash dangles from a tree. On the ground, a man tries to coax his pet back down to the sidewalk. Up in the tree, the man’s companion stalks the branches for his kill — a squirrel that messed with the wrong house dog. A photograph sent to Brisbin shows the unusual stunt.

This is what it is like to be owned by a New Guinea singing dog, known as singers to their rarefied fan base. Others who took the dogs sold off by zoos relate similar experiences.

“They’re described as something between a monkey and a cat,” says McIntyre. “They’re escape artists.”

~~

A year after McIntyre’s blood draw, Dr. Heidi Parker is in her laboratory, scouring microchips of genome sequences for biological secrets. A scientist at the National Human Genome Research Institute, she works with principal investigator Dr. Elaine Ostrander on everything from cancer genetics to the exact proportions of poodle and Labrador retriever genes in the genome of the labradoodle. Today, she is comparing the genomes of the New Guinea highland wild dog and the captive New Guinea singing dogs of the United States.

Sophisticated genetic techniques have coaxed the genome from those syringes of blood collected high on a New Guinea mountain peak. Coiled within the DNA contained by each cell are precious clues to where this unusual dog fits into the larger canine family tree. By analyzing single-nucleotide polymorphisms, tiny regions of variation in the chromosomes, Parker hopes to establish the relationship between the two versions of the dog. As she peers at the glass slides of microarrays, a pattern emerges.

There is very little variation. The singing dog and the highland wild dog are one and the same. What’s more, the dogs are closely related to the dingo of Australia, solidifying a theory that the dingo and the highland wild dog share a common ancestor.

When this research came out in 2020, it put the three dogs — the New Guinea highland wild dog, the New Guinea singing dog, and the dingo — together on their own branch. Not long after, a separate study of ancient dog DNA, published by Science magazine in October 2020, identified the New Guinea highland wild dog as one of five distinct dog lineages dating back as far as 11,000 years.

How exactly these dogs relate to the early dogs of mainland Asia and to the dingoes of Australia will provide a crucial piece of the puzzle that is dog domestication.

Even so, resources are scarce for the dog’s conservation, both in the wild and in captivity. The International Union for Conservation of Nature, known as the IUCN, delisted the dog from its Red List of Threatened Species in 2019. Analyzing its genome is vital not just to its recognition as a unique evolutionary entity, but to its ongoing survival.

~~

Once again, we find the New Guinea highland wild dog plying uncharted waters — a living fossil, existing somewhere between wolf and dog, cohabiting with humans watching Netflix on the couch while its wild ancestors still haunt the perilous slopes of the New Guinea highlands.

The closest most of us will get to that sensation will be a cycad or a fern on the mantel. No one has a coelacanth hovering silently in their aquarium. But those who live with New Guinea highland dogs can claim that most unique of experiences, an enduring link to an ancient relationship between humans and animals.

And when these creatures sing, whether by our side or far off in the wilderness, the tenuous nature of coexistence reverberates through the millennia. Like our ancestors, we have forged a relationship with something that is more than a little wild.

A glimpse of New Guinea highland wild dogs in their natural domain. Photo: Courtesy New Guinea Highland Wild Dog Foundation.

Richard Pallardy

Richard Pallardy is a freelance science writer. He is endlessly fascinated by the behavior and evolution of living things. By writing about these subjects, he hopes to draw attention to their importance — and to the joy that this knowledge can bring to everyday life.

Never miss a story

Subscribe for new issue alerts.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive updates from Hidden Compass regarding new issues and other ongoing promotions such as workshop opportunities. Please refer to our Privacy Policy for more information.