Support Hidden Compass

We stand for journalism, science, history, and hope. Make a contribution to Hidden Compass and stand with us.

How the French Caribbean’s Last Traditional Boat Builder Preserves the Ways of his Ancestors

My feet are firmly planted on deck, but my knees and spine roll gently as the azure waves of the Caribbean Sea undulate beneath the ferry. Behind me, Guadeloupe — a verdant pair of islands in the French Caribbean that, when seen from above, looks like a butterfly — gets smaller. Despite sea-spray coating my glasses, in the distance I can just make out Terre-de-Haut, one of eight islets strung together in the archipelago of Les Saintes.

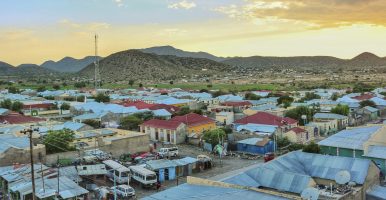

A tropical inlet on Terre-de-haut. PHOTO: SYLVAIN ABDOUL.

Terre-de-Haut is best known for white sand beaches and small, touristy fishing communities, but what makes the island compelling is its history. In the 17th century, as much of the Caribbean was being colonized and millions of slaves were brought from Africa to work the sugar plantations, Terre-de-Haut remained virtually untouched. The reasons why are no mystery: The island has neither its own source of fresh water, nor arid land for farming. Since time immemorial, Terre-de-Haut has been inhospitable — a place best left unsettled.

And yet, it became a safe haven.

People who leave the mainland to settle islands have both tremendous fortitude and also a stubborn will to live on their own terms. In English, we might call such people intrepid. In French, I’ve heard them called hurluberlus — eccentrics. Terre-de-Haut’s first inhabitants could very well have been hurluberlus, particularly as they didn’t even settle from the mainland, but from another island. Indentured laborers brought over from fishing communities in Brittany and Normandy, they were unable to afford passage back to France after finishing their contracts on Guadeloupe, and therefore sought a fresh start on Terre-de-Haut.

Jaggy, mysterious, and rugged. These words are often used to describe small outcroppings of islands such as Les Saintes, but they could also be used to describe the character of the people who inhabit them. Today, I’m hoping to meet one of them: the last traditional boat-builder in the French Caribbean.

~~

Alain Foy Jr. learned how to build boats from his father. Locally, he is something of an environmentalist: In the tradition of his forefathers, and in an effort to protect the waters around Terre-de-Haut, he uses all natural materials. Boats built of these ancestral methods and materials have not just dwindled — they have disappeared throughout the French Caribbean, making Foy something of a dinosaur.

I’ve spent weeks trying to locate him. I was thrilled to unearth his phone number and email address, but the calls have gone unanswered and the emails have bounced back — Internet access is spotty in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. Meeting Foy feels like a pipedream.

It seems I must track him down in person.

The ferry enters the half-moon of Baie des Saintes, and I look out over a collection of sailboats bobbing in the bay. Mick Jagger has moored his yacht here, and today, there are plenty of large craft that I imagine are owned by people with means.

Peppered among the yachts are plenty of smaller blue, green, and white Breton-style fishing boats. I wonder if any of them were made by Foy. I scope out the landscape. Soft heaps of cumulus clouds mushroom in the sky, hiding the horizon. Knowing Foy is within reach thrills me.

In the inhospitable modern age, Foy has both resurrected and reshaped the past.

Before I can fully situate myself in Bourg des Saintes, the small village that spills out from the port, I allow myself to be whisked off in a tour van through thin streets towards Fort Napoléon, one of the highest spots on the island. After parking close to the top, we look over the Baie des Saintes. Green hills, only somewhat denuded by the hurricane, rise from the bay, and dotting the shore is a collection of quaint homes, restaurants, and other businesses with bright red roofs and cheerful yellow and blue window shutters. The view is almost dizzying in its perfection. According to UNESCO, Baie des Saintes is the third-most beautiful bay in the world.

Our driver, Jimmy, a large, sturdy man with a brash-yet-congenial manner, stands to the side, his back to the spectacle below.

Stating the obvious, I nod towards the view, “It’s so beautiful.”

Jimmy lifts his dark brows, then shrugs and takes a drag of his cigarette.

On a whim, I ask: “Connaissez-vous Monsieur Foy?”

“Know him?” he responds, in English. “He’s my cousin.”

~~

An hour later, we’ve left both the tour group and the touristy areas and are passing farmettes with goats and chickens speckled across their fields. Then, to my delight, we come across a small, somewhat dilapidated disco near the water. In another minute or so, we reach a community known as le Marigot, and we pull off the one-lane road onto a thin, dirt path and hug the shore until we reach Foy’s boatyard.

Foy greets us at the door. His dark hair is short on the top, with dreaded locks pulled back into a band. He’s quick to smile, and when he does, his chestnut eyes shine. I like him immediately.

Behind Foy, I see the skeleton of a wooden boat, about ten feet long, resting on wooden horses in his workshop, and beyond, through large double doors, a picturesque bay. Foy puts his head together for a moment with Jimmy, who stands next to him in the doorway, and then looks at me with a broad smile.

“Oui,” he says in French. “I’ll tell you my story.”

We start at the beginning. In the early 1800’s, the first mayor of Terre-de-Haut was named Foy. “Are you related?” I ask him.

“Everyone on this island is related,” he laughs. “It’s why we’re all a little…” He trails off, spinning his finger in a circle in the air around his head. Then he tells me about his father.

For centuries, fishing boats made on Terre-de-Haut, known locally as Saintoises, were fashioned in the Breton style — made completely of wood, with round, U-shaped hulls able to carry a lot of cargo for their size. Foy’s father, Alain Foy Sr., learned the boat-building craft when he was a teenager, sourcing wood from local calabash and catalpa trees to be used in their construction.

By the 1970’s, Foy Sr. started equipping his Saintoises with outboard motors, and developed a new, V-shaped hull to increase speed. As other boat-builders started to use fiberglass and resin, Foy Sr. eventually bowed to the pressure, incorporating the new materials in place of natural wood.

Saintoise boats were not traditionally made with harmful chemicals and resins, and the use of these substances threatens marine life already endangered by overfishing, invasive species and climate change. It was out of his concern for the environment — as well as a desire to connect to his ancestors — that led Foy to revert back to older, more laborious methods of building boats, using locally-sourced wood from fallen trees. And it is Foy’s ingenuity that has allowed his boats to not only compete, but, miraculously, out-compete his modern competition.

The Nautical Alchemist, Alain Foy Jr. poses for a quick photo in his workshop. Foy’s hand-crafted wooden boats are out performing their high-tech racing counterpart.. PHOTO: MELISA BANIGAN.

As I ask Foy to tell me more about his process, however, he interrupts me.

“I did not always want to build boats,” he says. “I wanted to be an alchemist.”

As in, a person who conjures gold from other elements?

Foy laughs. “My father wanted me to build boats, but I wanted to do my own thing. I wanted to be a chemist, but school was too expensive, so then, yes, I wanted to be an alchemist.”

Eventually, Foy took up his father’s profession. “My father retired,” he explains with a shrug, “and I felt I needed to continue the tradition.”

Then, Foy describes in great detail how he looks for trees that grow in the shapes he requires for his boats. The grain of the wood, he explains, must already be “boat-shaped.”

“The way they curve is very important,” he says, accentuating his words by running his hand through the air in an arc.

“I’d like to teach the young people [about all of this] in a school,” says Foy, “but not enough people are interested.” He points to his son, a man in his early 20s, who sits a few feet away.

“Will you continue the family business?” I ask the young man. He shrugs, noncommittal, just as I imagine Foy must have done decades earlier.

~~

Despite using the boat-building methods of his ancestors, Foy has added a contemporary innovation. Whereas the original Breton-style boats had U-shaped hulls, and his father invented a much faster V-shaped hull, Foy has made his own modification — an S-shaped hull that makes his Saintoises so fast, they win all of the local boat races. “Out of 40 boats that were in one race,” he says, “I built 20 of them.”

In fact, the incredible craftsmanship of Foy’s Saintoise Breton-style boats, partnered with their high speed, has caused all of the fifteen or so local fiberglass boat-building businesses to fold.

“To stay in business,” Foy says, resting an arm on one of his half-built wooden boats, “you need to be the best.”

Foy obsesses over his boats, but he doesn’t gloat. When he tells me his story, he does it with one hand lovingly patting the side of one of his half-built vessels. His is a tale not just of boats, but of family, and it seems that for Foy, there are very few distinctions between the two — they are each a legacy of the generations that came before.

In the inhospitable modern age, Foy has both resurrected and reshaped the past. He might not be an alchemist, but he performs magic nonetheless.

~~

The day is drawing long, so after a hearty thank you and a quick set of bises — one on each of Foy’s cheeks — we set off in the van.

I look out the window towards scenes that could’ve been lifted from hundreds of years ago: Sunlight glimmers on the waves, giving the illusion that the bay is a cauldron of molten gold, and Foy’s green and blue boats bob within it like precious jewels. Surely, if anything can keep the island’s traditions alive, it’s Foy’s nautical alchemy.

Melissa Banigan

Melissa is a journalist and photographer with work in the Washington Post, BBC Travel, and NPR, among many others.

Never miss a story

Subscribe for new issue alerts.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive updates from Hidden Compass regarding new issues and other ongoing promotions such as workshop opportunities. Please refer to our Privacy Policy for more information.