Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

Iwas in the air for a long time before I hit the water. Submerged in the shadowy depths of the Manziwayo River, kicking back to the surface, I felt like I was home.

Memories deep within my body – memories I had forgotten – surged breathlessly to the rocky edge of the pool with me, summoning laughter. This was the water I swam in during another life. A life I had left behind nearly 20 years ago. In that moment, its taste, its temperature, its roar of cascades, came rushing back. But the water was not the same; I was not the same. So much had changed — mostly for the better. In the dusk of 2017, I returned to the remote gorges etched into South Africa’s Tugela Valley with two objectives: Recapture the magic that defined a formative period of my youth and reconnect with a community, to see how it had transformed.

~~

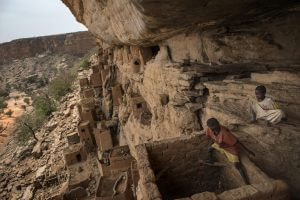

On its eastward journey from the mountains of Lesotho to the Indian Ocean, the Tugela River flows through the Nkandla district of South Africa’s KwaZulu Natal coastal province. This region gained fame recently as the birthplace of the country’s President Jacob Zuma (and infamy as the site of his expensive private residence). Thirty-five kilometers from the farming outpost, Greytown, the pavement ends in the province. Sixty kilometers of weaving dirt road later, you reach the heart of the Tugela Valley and the village of Mfongosi. In 1998, I found myself in this ignored backwater — where the Manziwayo River and Mfongsi stream converge in a bend in the Tugela River.

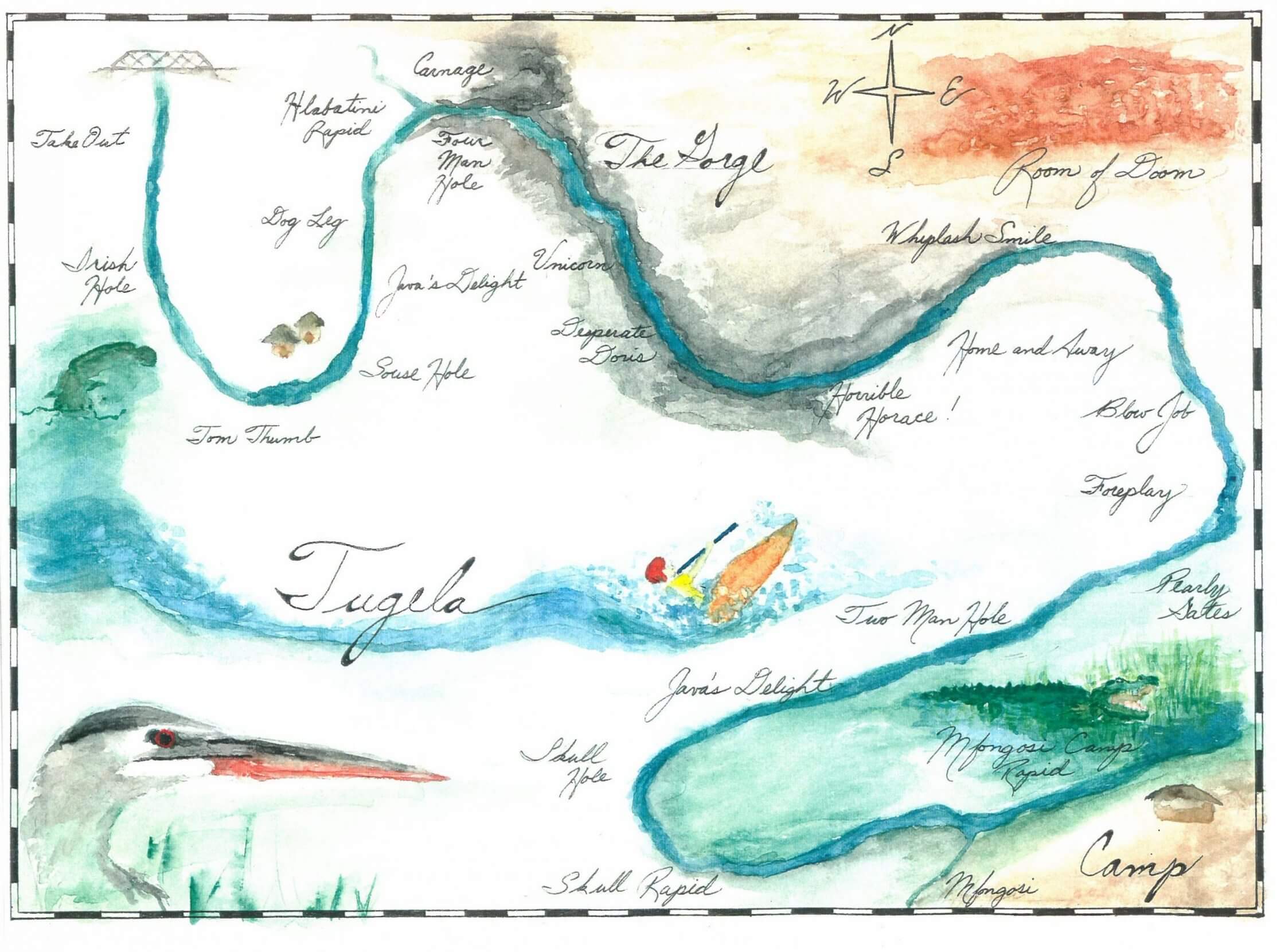

A map of the Tugela. Two decades after author Nicholas Bratton worked as a river guide on the Tugela, he returned to reconnect with the community that had been so important to him in his youth. PAINTING BY JOSEPH KELTY BUMP.

On the Tugela’s rolling, grassy banks was a modest camp. Crocodiles lurked in the shallows, rapids swallowed big red rafts, bad music blared from the bar, and lunch wasn’t served until you had leapt off a cliff. This was a largely unknown adventure capital of South Africa — my home from November of 1998 to April of 1999. As the only full-time guide on staff I devoured a steady diet of the Tugela’s thundering whitewater, as well as bum slides, abseiling, and cliff jumps in Manziwayo Canyon. The flow of life mirrored the river — bursts of adrenaline-fueled action separated by stretches of calm. When camp was empty I worked on maintenance projects and spent the heat of the day reading. When clients rolled in, it was showtime, pouring drinks at the bar, serving meals, crashing through waves, and sliding down waterfalls. I spent nights on the kitchen’s roof, watching satellites, and dreaming beneath a boundless African sky.

Crocodiles lurked in the shallows, rapids swallowed big red rafts, bad music blared from the bar, and lunch wasn’t served until you had leapt off a cliff.

Although I was a newcomer to South Africa, I had roots in the region. My grandparents lived in Rhodesia and Zimbabwe for more than 50 years, my father grew up in Rhodesia, and I spent three primary school years in Zimbabwe. This history planted my seeds of adventure, starting with a drive into the Kalahari Desert at age six with my parents. In the nineties, I had relatives in South Africa, and there, I felt a sense of belonging and familiarity.

~~

Mandela was in the twilight of his presidency in a hopeful young nation, yet the specter of apartheid was still present during my time working at the camp, just four years after the country’s first democratic election in 1994. A white married couple from Cape Town and Canada ran the camp and they supervised a staff of villagers. I viewed their relationships with people in the village as transactional — buying gasoline, summoning strong backs for heavy lifting, or using the police station as a car park. With no public investment in the area, the valley’s wealth was in wandering livestock, subsistence farming, and remittances from residents who had left for brighter prospects in mines or cities. But I tried to go deeper.

During ebbs in action I got to know the staff and learn a little Zulu over lunches of beans and maize. Among the rotating cast of part-time guides I befriended, the most memorable was Hugh du Preez, a kayaking instructor and talented paddler. Hugh questioned people’s basic assumptions in a way that elicited self-doubt and laughter in equal measures. Many of the rapids on the Tugela terrified me, but Hugh routinely paddled through the most violent waves like he was having breakfast in bed. There was no doubt in my mind of whom to invite when the call of the river became too strong to resist.

~~

In November of 2017 I returned to the Tugela. The original rafting company had folded due to complicated logistics and increased expenses. In the United States, I had honed my rafting skills on the steep and snow-fed rivers of the Pacific Northwest in Washington. When I met Hugh at a Greytown gas station, we were both older and grayer, but it felt like hardly any time had passed. With him was the next generation of South African whitewater guides, all of whom were strangers to the valley. Gustav Greffrath was the owner of an adventure guiding company called Itchy Feet that spanned river, mountain, and bush, and Godfrey Tshumah was one of his trainees.

Floating down the Tugela, I was hopeful for a future where the Rainbow Nation — Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s description of post-apartheid South Africa — and its visitors, could experience the wilderness without race barriers.

Godfrey was from Zimbabwe and had moved to South Africa nine years earlier, where he learned Zulu and discovered his love for wilderness and adventure, and we connected over our memories. Gustav told me Godfrey had personable skills that were hard to teach, and could help clients get the most out of a trip. Floating down the Tugela, I was hopeful for a future where the Rainbow Nation — Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s description of post-apartheid South Africa — and its visitors, could experience the wilderness without race barriers.

Hugh and Gustav said the greatest change in the industry since I had left was competition because adventure-seekers now had more choices for thrills. Motorized activities like quad biking had come onto the scene. Zip-lining gave people a taste of excitement while staying closer to home. In an era of social media, instant gratification, and compressed attention spans, rafting was a big commitment. Successful operations, such as Zingela Camp, which ran a section of the Tugela further upstream, had diversified into abseiling, mountain biking, fly fishing, paintballing, and birding, to entice more tourists.

Gustav had adapted his business to this shift, but he wondered: Could rafting regain its popularity or succeed on this remote stretch of river? He told me he believed the experience was special — a wilderness expedition that required time and was an opportunity to disconnect from modern technology. Gustav’s operation was mobile, meaning he could bring clients to the valley as part of an extended trip instead of trying to restore the permanent camp. It was a topic that Hugh raised frequently. The changing business model was a sign of the times like the village that surrounded us.

In Mfongosi, where I remembered crumbling mud huts, there were freshly-painted block homes. Celebrations rang out in 1999 when Telkom installed a solar-powered radio telephone in the village. In 2017, cell phones were everywhere. Satellite dishes adorned many houses like ostentatious grey earrings. Cars sat next to a handful of homes — personal transportation that was absent in the nineties. I saw fewer farm plots, although livestock still grazed the dusty earth. In the center of the village stood a covered taxi rank and a nearby clinic had expanded. Modest progress was evident even amidst apartheid’s neglect.

~~

“Bayete” is the respectful Zulu greeting to a chief and Godfrey and I headed to the fanciest house around — a lavish gated compound of nine homes with manicured lawn — to deliver that message to the most powerful man in the village. A gardener told us we were at the home of a taxi company owner and that the chief lived next door.

A bald, bare-chested man with a pot belly and grey beard greeted us at the gate with the enthusiasm of a long-lost friend. Nicholas Mfana Ntuli was the chief’s second-in-command and he had seen me driving around in a white Land Rover and had said he was expecting us. With a warm handshake, he invited us into his home, since the chief was out on business.

Seated inside the dimly-lit living room on plastic-covered furniture listening to a flat-panel television barking English news, we could have been anywhere in South Africa. A cow grazing outside the front door was the only clue that we were in Mfongosi.

Nicholas was upbeat about the quality of life in the valley and highlighted major improvements as I had already observed.

Homes had electricity and water. Roads were better and tar was coming. Four school buses carried uniformed children to classes at a school where I had dropped off gifts of chalk, pens, and notebooks. I had learned during my visit to the school that many of those children were going to University of Zululand, or colleges in Pietermaritzburg and Durban — in a country where the unemployment rate is nearly 28 percent. A bridge and new homes were scheduled for construction. The community gained a second clinic and two more high schools. People who had moved away were now returning.

Nicholas’ views of progress mirrored my own but he added that economic development wasn’t keeping up with growth, and jobs were still scarce. His stories of families selling their livestock to launch small stores selling drinks, snacks, and cellphone airtime, revealed the need for investment beyond the river camp’s economic benefit.

Nicholas shared his nostalgia for the rafting era, as the area’s once great commercial enterprise.

I left him with a t-shirt from my home city’s soccer team — the Seattle Sounders.

“Clint Dempsey!” he exclaimed, reading the name on the back of the shirt. “Didn’t he used to play for West Ham United?”

Suddenly my world felt smaller. This man in a remote village in South Africa knew more about my hometown players than I did. Soccer really is a universal language, I thought.

That night, I fell asleep on the Land Rover’s roof, watching stars cross the sky like I used to above the camp’s kitchen. I felt hopeful that I would return to leap into the pools of the Manziwayo.

Nicholas Bratton

Nicholas is a lifelong adventurer and traveler with a knack for finding unexpected ways into unusual situations — like guest DJ-ing on Zambian national radio.