Support Hidden Compass

We stand for journalism, science, history, and hope. Make a contribution to Hidden Compass and stand with us.

When I first laid eyes on her, she was perched in an arched window of a crumbling stone building, staring in my direction. She instantly drew me in. Yet I knew we’d never meet — not in any ordinary sense.

I was roaming Lisbon’s Feira da Ladra, my favorite flea market in Portugal, on one of those late October days when the low-hanging Mediterranean sun casts long, spindly shadows. Everyone was taking it in. Outdoor cafes were crowded. The river, dotted with sailboats, shimmered. And the flea market bustled with merchants and searchers like myself.

I wandered past heaps of used clothing in earthy hues, past the button man playing his accordion, past the antique booksellers and the brass-door-knocker hawkers and the woman selling well-worn crucifixes.

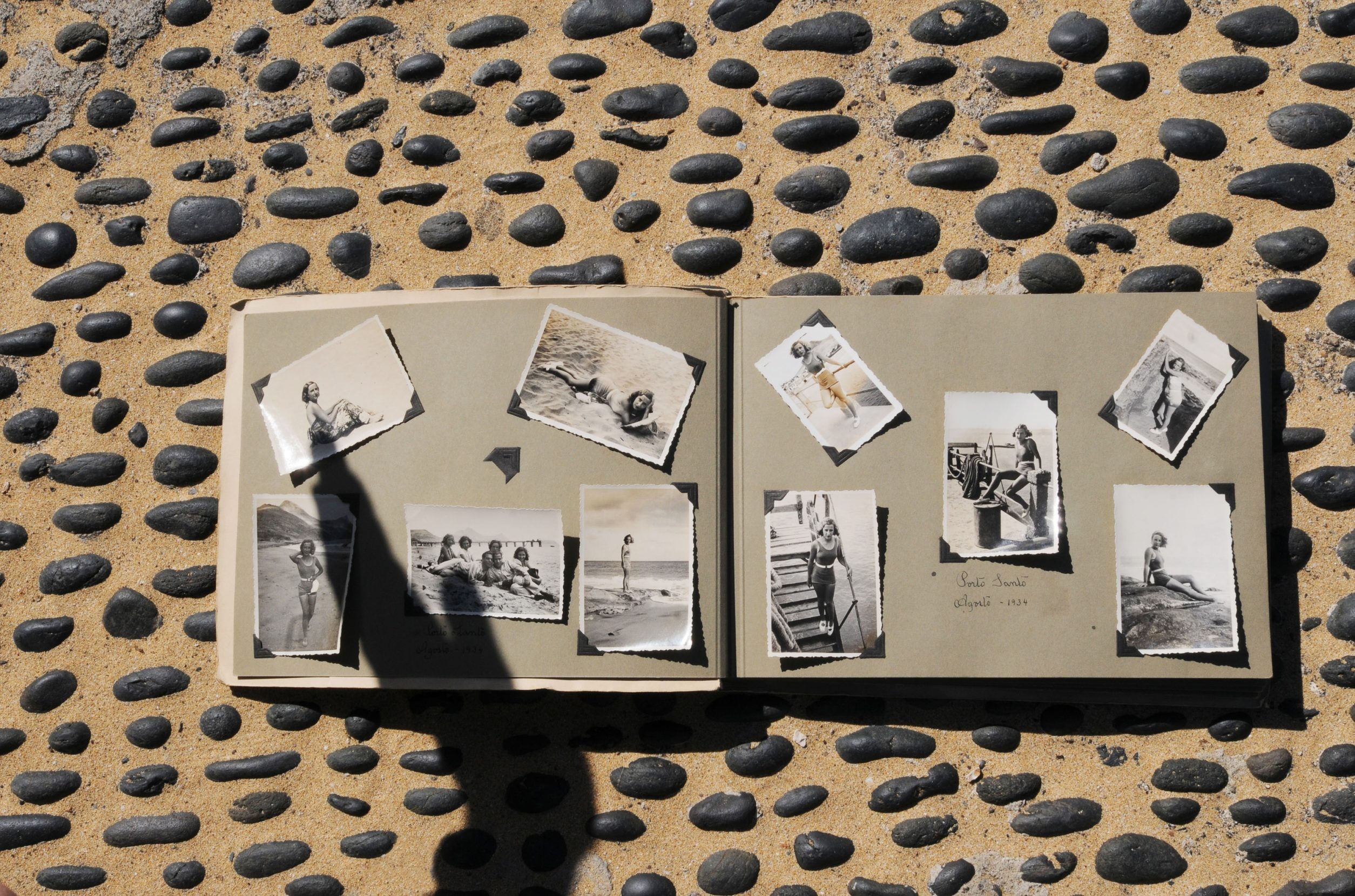

I spied an old photo album sitting on the corner of a blanket. The vendor took note of my double take. The weekend prior, he’d sold me a pair of fake Adidas whose soles had since melted. I shot him a skeptical glance, crouched down, and opened the album to find thick, gray pages filled with black-and-white snapshots. And there she was, looking out from that window.

The woman whom writer Melinda Misuraca named Valentina perches in an old window on the Portuguese island of Porto Santo circa 1934. Photo courtesy of Melinda Misuraca and Russell Porcas.

I didn’t even bother to haggle. I paid and took my new treasure to a café, where I examined it as I drank a meia-de-leite.

The young woman whose images had caught my eye was clearly the jewel of the collection, still radiating from those old snaps. She’s at ease in front of the camera, whether sun kissed and laughing or solemn and daydreamy, her face half in shadow. The photographer had a percipient eye, capturing more than the woman’s beauty. Had they been in love, and had it lasted?

In most shots she’s alone, though in some she shares the frame with a couple of young women who look to be sisters, and a handsome, smiling priest in a bowler hat, who strolls with them on the beach, holding a camera, or playfully lounges with them in the sand. He and the woman in the window stand out from the others, as if lit from within — the young woman who goes her own way and the buoyant man of the cloth.

Four young women, including Valentina, lounge on the beach with the mysterious Catholic priest. Photo courtesy of Melinda Misuraca and Russell Porcas.

Of the more than one hundred snaps in the photo album, most are set in a volcanic landscape labeled in pencil: Porto Santo, 1934. A tiny, subtropical island in the Madeira Archipelago, Porto Santo sits in the Atlantic about 600 miles from Portugal. Wind-sculpted sandstone, a pristine beach, lava cooled into accordion-like columns, panoramic views from mountain peaks — these were the mystery woman’s backdrops, 80-odd years ago.

The volcanic island of Porto Santo stretches into the distance. Photo: Russell Porcas.

She and her priest friend must have been rare creatures indeed, back in the 1930s on such a secluded, robustly Catholic lump of volcanic rock.

~~

I’d moved to Portugal six months earlier, in the spring of 2019. Whenever somebody asked why, I’d tell them about my grandmother’s watercolors depicting Portuguese scenes of the 1940s: pigeons strutting along terra-cotta rooftops, children playing in alleys, housewives hanging laundry from balconies, fishmongers pushing their carts. I’d talk up the bowls of caldo verde I’d eaten, made by a Portuguese-American friend blessed with fabulous eyebrows. I wouldn’t mention my lifelong struggle with restlessness, how it continues to propel me into the unknown, consequences be damned. Instead, I’d just say that I’d needed a change.

Once in Portugal, I haunted flea markets and junk stores, scrounging for old photos. I’d collected cast-off snapshots for years, a pastime that scratches several itches: the thrill of never knowing what I’d score, flavored with the curiosity-stoking disciplines of history, art, and anthropology, plus a splash of intrigue, a dash of the existential, and a jigger of voyeurism.

Now my hobby helped ease my homesickness as I slowly took root in a new country, forcing me to interact with strangers and work on my Portuguese. I’d sort through shoe boxes stuffed with photos, taking home shots of ordinary folk who were likely long dead, yet whose caught moments allowed me to get to know them a little, understand what had mattered to them. In time, these snapshots grew into a sort of ghost family.

But this woman in the window would become something more.

She’d bewitched me. I carried her album around like a lucky charm, as if it could ward off the turmoil and treachery of the world. I couldn’t find her name written anywhere, so I gave her one: Valentina.

The photo album was discovered at a flea market in Lisbon. Photo: Russell Porcas.

~~

Later that fall I fell for a cute, silver-haired British photographer who’d lived in the Mediterranean for decades. On our first date, Russell and I sat on a bench in a plaza in the shadow of a castle and bonded over our love of photos, old and new. Not long after, he lured me into a relationship with him and his camera. Reluctant at first, I eventually relaxed and learned to ignore him as he snapped shots of me and our everyday life.

I told him how I felt drawn to find Valentina, how I wanted to track down someone who’d known her, even loved her. I would never truly get to know her myself, and yet I felt compelled to try. But did I have the right to go digging into her past?

In the meantime, Russell and I had gotten ourselves hitched in California. Then we were back in Portugal, riding out the pandemic. We spent the long months of lockdown walking in the countryside, waving to farmers as we passed their fields and hiking to crumbling windmills on oak- and olive-covered hilltops.

In the evenings we’d hole up in our rented stone cottage, where Russell would digitally scan and restore the snapshots of Valentina. He was especially fond of the “swimming costume” poses — her sun-streaked curls clipped into a pageboy, her clingy, knit one-piece worn with twee Mary Janes. Who could blame him? As he meticulously worked on the “spotting and dotting,” as he called it, she’d bloom with life.

Meanwhile, I trawled history books and online archives. I didn’t find the woman I was looking for there, but another character — Porto Santo itself — began to take shape in my mind.

~~

First documented on a 14th-century Italian portolan chart (an early nautical map hand-drawn on vellum), Porto Santo was once a way station for ships sailing along the Atlantic coast. It’s thought that Vikings anchored near the island in the eighth or ninth century (the evidence: a distinctly Nordic mouse still scampering around there today). But it remained a lonely secret until Portuguese explorers João Gonçalves Zarco and Tristão Vaz Teixeira — returning home after nosing around Africa for land to plunder — blew in on a storm. They named the island Porto Santo, or “holy harbor,” for the safety it offered.

Yet despite its isolation, Porto Santo was repeatedly ransacked over the centuries by marauders from the Ottoman Empire, France, England, and elsewhere. Whenever pirates turned up, some villagers managed to escape by boat, hiding in caves on nearby islets. Others lit bonfires at the top of Pico de Facho to warn nearby Madeira Island of the danger afoot. One harrowing account tells of Barbary corsairs who captured women from Porto Santo, raped and impregnated them aboard ship, then released them back ashore to populate the island with Moorish blood.

Cristóvão Colombo (that guy) spent some time on Porto Santo, marrying Filipa Moniz Perestrello, the daughter of the island’s first governor. She gave birth to a son but died soon after, and Colombo left the child in a Spanish monastery before sailing off on the first of his four voyages westward. The simple stone house where he once lived still stands and is now a museum.

Other island lore includes that of a 16th-century cult begun by a hermit and his disabled niece. Under their unlikely leadership, it had flared up in glorious hysteria, complete with naked, sin-dissolving rituals. Such arcane naughtiness was ultimately snuffed out by the sanctions of a visiting bishop from Madeira.

I began to feel an undertow carrying me toward Porto Santo. Valentina, however, remained an enigma. My inquiries to genealogical archives in Madeira had proved fruitless.

~~

Once the lockdown was lifted in Portugal, I begged Russell to travel with me to Porto Santo. We couldn’t really afford it, but eventually I wore him down. I was going to go anyway, with or without him. So in mid-October, exactly one year after I’d found Valentina in the Lisbon flea market, we flew into the island’s tiny airport, armed with Russell’s camera and the photo album.

Mystery is a refuge, spangled with possibilities. When the siren calls, I say yes.

A friendly taxi driver offered us his tomato soup–colored beater for 20 euros a day. Its floorboards were carpeted with sand and its ashtrays stuffed with cigarette butts, its brakes were shot, and two of its windows wouldn’t roll down. Yet we were stoked to have it.

As we drove up the narrow, winding, cliff-hugging road to our home-for-a-week, Porto Santo’s mountains rose up before us in a desolate, stunning display, a ragged line of fawn-colored dollops formed by the tantrums of an undersea volcano.

Legend has it that Porto Santo, like neighboring Madeira, was once covered in forest, but a 15th-century sea captain released a pregnant rabbit on the island, and the native greenery was eventually devoured. Porto Santo’s desertified landscape is a somber glimpse into the planetary future, where geologic splendor and environmental catastrophe coexist.

On our first morning we headed to Vila Baleira, Porto Santo’s main village, to visit Casa de Cristóvão Colombo. Senhora Sofia was the newest docent at the museum, and the only one fluent in English. Both reserved and gregarious, she immediately put me at ease. She had a face prone to slapstick contortions, along with wheat-colored hair and blue-green eyes she said proved she’d descended from pirates.

Senhora Sofia’s parents are first cousins, a detail she offered in a stage whisper, explaining that such unions are common on Porto Santo and give the family a sense of security and safety — words she often used when describing her life relative to the outside world. Out There, she called it, and shuddered.

After we showed her our photos, she mentioned a man named Senhor António, the honorary island historian, and offered to phone him for us. We made a plan to meet with him at the museum the following day.

We arrived early and wandered the courtyard of Colombo’s house. A tree grew just inside the gate, with bloated-looking limbs and a canopy of spiky leaves. The Dracaena draco, or “dragon tree,” is an indigenous evergreen and a source of “dragon’s blood,” a resin once valued for its dye and medicinal properties, and used as both a stain and varnish for Stradivarius violins. I’d read that this precious elixir had fetched a top price during the 16th century, when the tree was harvested and traded almost to extinction. I scratched the thin bark with my fingernail, and a crimson-colored sap bled out. I fought back an urge to taste it.

Senhor António looked to be in his 70s, carefully groomed, in a black pleather jacket and slacks. He examined the photo album, poring over each snapshot with a magnifying glass, his manner polite yet intrigued.

“They’re not from Porto Santo,” he said. “Portsantenese would never go to the beach for pleasure. They were farmers and fishermen, too busy working. These people might be from Madeira.”

Senhor António explained that during the 1930s, Madeirans sailed to Porto Santo in the summer months to enjoy the five-and-a-half-mile-long beach of golden sand, which — along with the local mineral-rich spring water — was thought to contain therapeutic properties. Back then, Porto Santo was called Ilha Dourada: the “golden island.” Passenger sailing ships would anchor just beyond the shallow waters, and local fishermen would carry intrepid holidaymakers to the beach on their backs. Unlike Madeira in the ’30s, when swanky resort hotels, golf courses, and indoor plumbing catered to steamship travelers, Porto Santo offered sparse accommodations, and modern sanitation was a distant fantasy. Roads were rugged, the transport choices ox cart or burro. Ecotourism, long before it was cool.

Porto Santo’s honorary historian, Senhor António, shuffles through the old photos of Valentina and her friends. Photo: Russell Porcas.

~~

According to Valentina’s penciled dates, she’d traveled to Porto Santo several times in 1934 and 1935, thoroughly exploring the island. Her album was divided into sections, each labeled in pencil to correspond to a landmark. Salinas. Ponta da Calheta. Lombas. Fonte de Areia.

Russell and I set about finding them. They were scattered around the island, some difficult to reach by car. On particularly sketchy roads I resorted to the spontaneous prayer of the terrified unbeliever.

One afternoon we went to see the swirly, peach-colored sandstone of Fonte de Areia. Along the dirt track to the once-popular fountain and picnic grounds, now mostly derelict, the stone was covered with carved graffiti. But the cliffs where Valentina and her companions had climbed up in their Sunday best, tucking themselves into nooks and crannies among the cake-frosting rock formations, were as eerily enchanted as they’d appeared in 1934.

Several of the album’s photos had been snapped on treacherous mountaintops, where we found flimsy railings slapped together from branches, as if to suggest that on Porto Santo safety is a state of mind.

Russell and I had planned to replicate Valentina’s photos, with me as her proxy, a silver-haired, bespectacled grandma perched like a mermaid atop a dark igneous rock, staring into the camera lens with a come-hither look. Instead we found each of the locations and hung around for a while, lit up with déjà vu. Back on the mainland, we’d sustained ourselves through the months of lockdown by imagining these places in color. Now their realness made us feel drunk.

At a viewpoint called Miradouro Flores, where Valentina and her posse were photographed along with an oxcart driver, we watched three middle-aged men pull up and burst out of a Fiat. They took turns on a homemade swing set at the edge of the cliff, snapping selfies with their feet pointed into the sunset and cackling like adolescent boys. Then they jumped back into their car and drove off.

At Ponta de Calheta we recognized a rocky outcropping pictured in a favorite photo from the album, though the movement of sand over the decades had partially obscured it. I stood where she had stood and leaned against the rock she’d leaned upon, and waited for Valentina’s ghost.

But there were no questions or answers, nothing to find. She and I had briefly floated over the island like transparencies. Snap.

Hours flicked by. Every day for lunch Russell and I ate freshly caught seafood and bolo de caco, a traditional griddle flatbread made with sweet potatoes and drenched in garlic butter. In the afternoons we’d walk through pine forests and past vineyards tucked among the sand dunes, past the tumbled ruins of stone dwellings, where men in camouflage hunted for rabbits — perhaps the descendants of a sea captain’s pet.

The writer and her photographer husband, Russell Porcas, find the rock outcrop where Valentina once posed in 1934. Photo: Russell Porcas.

Driving home at the end of one day, we stopped near some old windmills to feed a tethered horse and watch the sky and sea, which looked as if an artist had splashed pigments around — cornflower blue, cotton candy pink, lavender, caramel, moonstone. No wonder Senhora Sofia never wanted to leave.

~~

Valentina poses beneath a rock arch at Ponta da Calheta. Photo courtesy of Melinda Misuraca and Russell Porcas.

On our last day in Porto Santo, we went back to Ponta da Calheta, where Valentina is framed under an arch made of rock, her body a dark shape against the sunlight bouncing off the sea behind her. Walking back to our car, we came upon a huge dragon tree suspended from a crane high above, slowly being lowered into a massive hole. Others had gathered to watch in silence, as if witnessing a ceremony.

Then we stopped at Casa de Colombo to say goodbye to Senhora Sofia. She gave us her email address, though she said she probably wouldn’t answer any messages, as she’d yet to learn how to email. “Don’t use my real name in your story,” she added. “I don’t want my life to change.”

As we drove back over the mountains, I felt the last shreds of time dissolving, leaving me dusted with sadness. My journey to Porto Santo had become a memento mori of sorts: While I’d found no distinct artifact of the long-dead Valentina, I felt I knew her more intimately than before. This island had lured and entangled me.

~~

Back home on the mainland, I bought a book from a Madeira historical website. It arrived in the mail a week later. Its pages were filled with images of Porto Santo, shot between the 1930s and ’70s by a priest from Madeira named Padre Eduardo Nunes Pereira and published 40 years after his death. Several snapshots of him were included. When I saw them, I froze.

He was the priest in Valentina’s album.

Padre Eduardo, I soon learned, was not only a priest but also a journalist, photographer, historian, musician, and singer. He penned a well-regarded history of Madeira and Porto Santo called Ilhas de Zargo (The Zargo Islands). According to the book’s introduction, Padre Eduardo saw Porto Santo as an “exilic refuge” where he took many photos, wrote articles about local customs, cataloged flora and fauna, drew maps, transcribed songs, and spent his last days.

The catalog had been published to mark a posthumous exhibition of the priest’s photographs, held at the Casa de Colombo three years before Russell and I had visited. The Portuguese president, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, had flown in to see it, and he swam in the clear waters near the golden beach. Yet neither Senhora Sofia nor Senhor António had made the connection between the legendary Padre Eduardo and the priest in Valentina’s photo album.

I wondered about this charismatic priest and his relationship with Valentina. Were they relatives? Friends? What did they talk about?

The mysterious Valentina on the island of Porto Santo. Photo courtesy of Melinda Misuraca and Russell Porcas.

The Pereira family has lived in the Madeira islands for centuries. I scoured genealogy sites and constructed a family tree, which eventually led me to Senhor João Pereira Prudente, a retired professor living in Funchal, Madeira, and the grandson of one of Padre Eduardo’s brothers. I emailed him a bundle of photos. He was friendly and tickled by my search.

“That’s my grandfather, that’s my great uncle,” he wrote. “And that,” he added, identifying a smiling young woman often seen palling around with Valentina, “is my mom.” He shared the photos with some cousins, who identified more family members. But despite circling ever closer to Valentina, nobody could figure out who she was.

Eventually, with the help of genealogy sites and the process of elimination, I twigged on a theory that Valentina’s real name was Philomena and that for a short while she’d been married to one of the priest’s younger brothers. Further poking around led me to her daughter Vera, now in her 80s and living in South Africa. I found her on Facebook, introduced myself, and asked if she would be willing to talk with me.

“Who are you?” she demanded. “How did you find all these details about me? What do you want?”

I explained my quest, how I’d found the album in Lisbon and gone to Porto Santo to look for Valentina. Her mother.

“I don’t believe you,” she said. “Something doesn’t add up.”

“I’m happy to give you the album,” I wrote, cringing as I typed, “if you can confirm she is your mother.” I sent her some of the best Valentina snapshots.

“She’s not my mother,” Vera wrote back.

Her mother, it turned out, had been married to Carlos Pereira, one of Padre Eduardo’s brothers, and her mother’s name was Philomena. But she wasn’t Valentina, the woman in the window. Vera sent me a photo of her mother from the same era. She was a dark-haired Portuguese beauty, and when I complimented the snapshot, Vera softened and told me a little about her.

As a young wife living in provincial Madeira, Philomena had longed for adventure. After two years she divorced Carlos and sailed to South Africa, where she met and fell in love with a man 20 years her senior, who happened to already have ten children. They married, and she gave birth to Vera. After Vera’s father died, Carlos wrote many letters to Philomena, begging her to return to Madeira. She never did.

Vera offered to ask a few relatives if they could identify Valentina and said she’d get back to me. The next morning, a message was waiting.

“You came knocking on the wrong door,” Vera wrote. “Do you have nothing else to do but look around for dead people’s ancestors? Sad, living off the corpses of strangers.”

Stunned, I tried to salvage the delicate rapport we’d had the previous day, but my words just seemed to anger her more.

~~

Vera’s words shook me up, leaving me jangled with doubt. No wonder she was suspicious of me, a stranger who’d chased her down to ask personal questions about her dead mother.

And yet I couldn’t let Valentina go. I vowed to keep looking for her, hoping to do it with humility and respect. What would Valentina say about me electing myself her memory-keeper? I couldn’t ask her, so I answered for her.

As if we were friends.

~~

I knew we’d never meet — not in any ordinary sense.

It’s been nearly three years since my first glimpse of Valentina, and I still haven’t found her. I keep turning over this shell, moving that one around, looking under another. I recently scrolled through a Facebook page devoted to sharing old photos of Porto Santo and came across two images of Valentina — one in which she’s riding in an ox cart, the other a swimsuit snap taken on the pier, with the iconic Pico Castelo in the distance. The page’s owner can’t recall who submitted the photos, though he’s promised to keep looking.

Not long after, Senhor João, the retired professor, messaged me with exciting news: A cousin, he said, had unearthed a photo of family members hanging out with Valentina.

Thinking over this new development and reading his detailed email — with his promise to keep looking for “this mysterious person,” as he called her — something else hit me: She was our Valentina. Not her body, not her memory, not her self, but what she created, without even knowing it.

I’ve never met Senhor João in person, but I could have kissed him on both cheeks, Portuguese-style. I think I knew, in that first moment in the flea market, that if I went looking for Valentina I’d find a story. What I hadn’t foreseen was how deeply it would become part of my own, and even the stories of others. Our, we, us.

I’m not religious, nor am I an atheist. Letting curiosity take the lead is about as close to following God as I’ll probably ever come. Mystery is a refuge, spangled with possibilities. When the siren calls, I say yes.

I’ve tracked down a crumbling old copy of Padre Eduardo’s Ilhas de Zargo, and I’m attempting to translate it into English. It’s clumsy, tedious work — and I love it. Every word is a fleck of gold.

Misuraca examines a beach where the enigmatic Valentina once stood. Photo: Russell Porcas.

Melinda Misuraca

Melinda Misuraca is a writer who likes having conversations in parked cars, taking naps in meadows, and drinking cold, bitter beers while shooting pool.

Never miss a story

Subscribe for new issue alerts.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive updates from Hidden Compass regarding new issues and other ongoing promotions such as workshop opportunities. Please refer to our Privacy Policy for more information.