Support Hidden Compass

We stand for journalism, science, history, and hope. Make a contribution to Hidden Compass and stand with us.

CONTENT WARNING: This story contains graphic content and descriptions of sexual abuse involving a minor. Reader discretion is advised.

***

In my beginning is my end. — T.S. Eliot

Friday, July 24, 1998 / 2:29 a.m.

Aboard The RSV AURORA AUSTRALIS

100 miles off the Antarctic coast

One long, ear-thrumming alarm jerks me from the edge of sleep. A fire drill? At this hour?

I struggle from beneath the blankets of my narrow bunk, open the cabin door, and wince at the bright light of the ship’s empty companionway.

“Is this a drill?” I ask a scientist who stumbles past. He sleepily shakes his head and shrugs.

The alarm stops. I pause in the doorway and will the silence to settle in.

I detest middle-of-the-night surprises. Always have.

~~

The edge of the mattress tilts.

But it’s the breathing that sets my heart racing.

~~

The alarm erupts again.

“Attention! Attention, please! There’s a small fire in the engine room.” The captain’s voice, tense and remote, issues from the ship’s loudspeakers. “Please muster to the heli-deck.”

My roommate, a penguin researcher, shakes herself awake and rolls out of her bunk. She steps into her “freezer” suit, designed to withstand temperatures as low as minus 4 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 20 C). I don a turtleneck sweater, pullover, jacket, long underwear, sweatpants, socks, and wool-lined boots.

I start through the doorway and — for a reason that I will never understand — dash back into the room to grab a small flashlight. I bought it in Hobart, Tasmania, the port we’d left eight days earlier, to quiet some mind-gremlins that had been shouting at me, “Don’t go! Don’t go! Go home! Go home!”

But my home was 9,000 miles away.

I’m on a seven-week expedition aboard the research icebreaker RSV Aurora Australis with several dozen scientists, technicians, and crew to explore the winter sea ice around Antarctica — a journey I’m chronicling for the Discovery Channel.

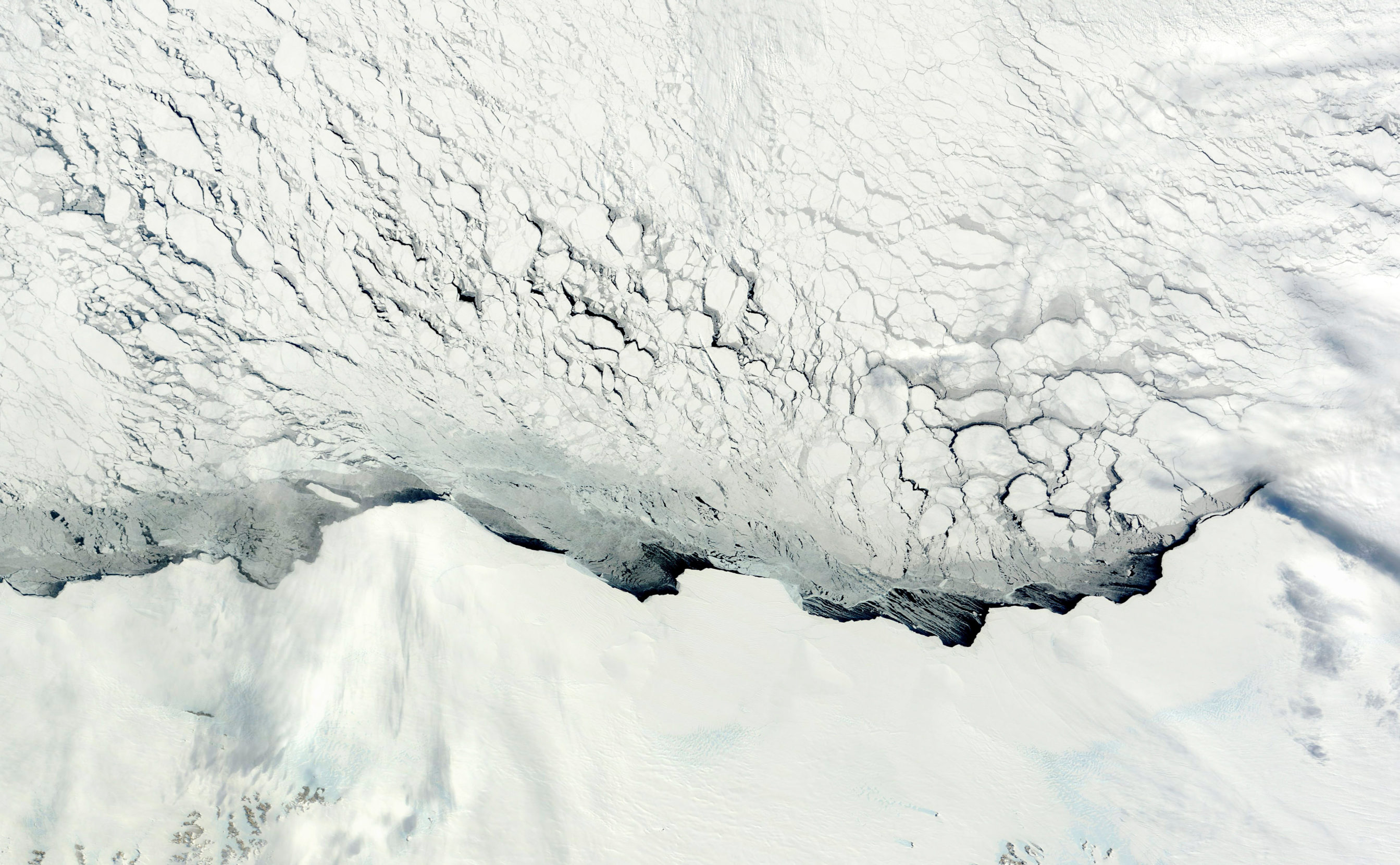

We’re exploring one of Nature’s most mysterious phenomena: Every year, starting in May, 20 square miles of sea freeze each minute in the ocean surrounding the Antarctic continent. By July, enough sea ice will form to double the size of Antarctica.

Life abounds in this ephemeral world, but for humans, it’s one of the most isolated, forbidding places on the planet.

In the bitter cold, in complete blackness, we all understand that something horrible has happened.

~~

I trudge with others single file toward the stern. As we emerge onto the helicopter deck, I smell smoke.

It’s frigid outside. Thick clouds solidify the moonless night. Floodlights punch holes of illumination onto the deck, which is covered with a thin layer of snow. Lowered lifeboats crouch in shadows along the railings.

Two seamen dressed in full firefighting gear stand with their hands locked in front of them, oxygen tanks and breathing masks at their feet. Grim-faced, they glance toward us but make no eye contact as we pass. My stomach tightens.

Unbeknownst to us, several decks below, the first and third engineers are aiming fire extinguishers at a blaze around the larger of the ship’s two massive engines. They extinguish the flames, but smoke still billows from both. The cavernous three-story room fills with the fumes of diesel fuel.

Just as one of the engineers yells, “I think the fire’s out!” a fireball erupts around the engine, and a whoosh of air and heat rushes at the men. One of them streaks up a ladder to the control room, dives through the doorway, and slams the watertight door shut. The other runs toward the back of the engine room and climbs an escape ladder to an upper deck.

When the engine-room explosion occurred, the ship was in a vulnerable spot: stuck in three-foot-thick sea ice 100 miles off the Antarctic coast — and 1,600 miles from the nearest port — with a blizzard bearing down. Photo: Fire and Flames / Alamy.

Six decks above, on the bridge, the captain feels the ship shudder as an explosion rips through the engine room. He grips the back of his chair and lowers his head to steady his nerves.

The alarm abruptly stops. The floodlights that illuminate our group on the open deck blink out. The captain yells at the radio officer: “Send Mayday! Mayday! Mayday!”

The international distress signal means the ship is in grave and imminent danger — of fire, explosion, or sinking — and requires immediate assistance. But the explosion knocked out the emergency generator that powers the radio. No message is sent.

A ship underway is a living creature: It inhales and exhales through its vents; water gurgles through its pipes like blood through veins; lights buzz 24 hours a day; and, beneath all the noisy burble of life, the engines are a comforting heartbeat.

But now the Aurora’s heart has stopped.

In the bitter cold, in complete blackness, we all understand that something horrible has happened. We’re 1,600 miles from the nearest port, adrift in solid sea ice a hundred miles off the coast of Antarctica, with a blizzard approaching. Planes can’t land on the three-foot-thick sea ice, and we’re out of range of rescue helicopters.

The massive Aurora Australis — 300 feet long and able to gnash fearlessly through nine-foot-thick ice — shrinks to insignificance.

~~

Until all on board are accounted for, the captain cannot take drastic firefighting measures to seal off part of the ship or order people into a lifeboat. The expedition member tasked with calling out names on the roster stammers, “I-I-I can’t see.”

I start through the doorway and — for a reason that I will never understand — dash back into the room to grab a small flashlight.

I remember the flashlight and point a tiny beam at the list. The chief scientist steps in to finish calling the names out in a strong voice. Three people are missing: the cook and two stewards.

Suddenly the voice of the second officer buzzes over the third officer’s radio: “The cook’s with me.” Someone else finds the stewards. After an evening in the ship’s bar, they’d slept through the alarm.

Everyone is accounted for. I switch off the flashlight.

In the blackness, snippets of transmissions between the captain and the crew crackle from the radio. “Preparing to drop halon. Waiting for muster station reports.”

Halon. Every ship’s engine room carries canisters of the nonflammable gas, which can snuff out flames instantly. It’s our only hope of survival.

We know that the fire’s heat must be melting the safety caps off the nearby liquefied-natural-gas canisters, which hold the ship’s fuel. If they explode, the ship will erupt in a mass of flame and burning metal shards. Some of us will be killed instantly. Others will be thrown into the pitch-black water and drown. A few people closest to the lifeboats might be able to scramble into them. But it’s unlikely that they’d be able to pick their way across a hundred miles of sea ice to the closest base on the Antarctic continent before they freeze to death or are crushed by ice floes.

Through the radio, the captain’s voice counts down to release the halon. “Three … two … one!” No one seems to breathe as we eavesdrop on our future.

I swivel my head, eyes wide in a struggle to see. Then the darkness seems to shift. Something colder, blacker, and quieter than the night surrounds us. A chasm stretches in all directions and seems to swallow any sounds we’re making — whispers, shuffling feet, puffs of warm breath. I’ve crossed some line between us and death.

I inhale slightly, the way one might to catch the scents of a street market in a foreign city. I probe too far, sense death’s cold precipice too clearly.

And then I detach.

~~

Dread overlies my fear of this familiar — this person and the inevitable exertion to come. My stepfather — who is finishing a doctorate in psychology and will soon become a respected member of the community — fondles my labia, clitoris, and vagina while wrapping my small hand around his penis. I already know that crying won’t stop this.

I dissociate.

Repressed childhood trauma, including sexual abuse, can cause toxic stress in our brains and bodies, which in turn can lead to poor health and bad behavior. Photo: Kritsada Seekham / Alamy.

~~

The icy wind, burning through every loose seam of my clothes, draws me back. My legs are nearly numb. I try to close the top of my life vest with the unfeeling stubs of gloved fingers.

As I vow to overprepare, overdress, and assume the worst if there could only be a next time, the halon snuffs out the fire. We know because the ship is still solid. We are still alive.

But not out of danger.

The engineers manage to start the emergency generator. A few weak lights slowly appear in isolated spots on the ship. Forty-seven minutes after the power died, the radio officer sends the Aurora’s first Mayday.

While some of the crew head to the engine room to confirm that the fire is out, the rest of us shuffle to the recreation room. Depending on what the crewmen find, our next move might be to abandon ship.

I feel as if I’m drowning.

Far below, two crewmen in firefighting gear crack open the hot door of the engine room and peer into a disaster. Their flashlights reveal strands of smoldering cables hanging like old spiderwebs, frayed and melted wires sagging on control panels. All the lights are shattered. The fire blackened everything.

While we wait in the rec room and take turns telling jokes to ease the tension, the crewmen vent the poisonous halon so that they can inspect the engine room — a process that takes several hours because of the heat and the danger of another fire.

The captain finally contacts the ship’s owner, P&O Maritime Services, in Hobart. Their managers assemble a technical staff to advise about the next steps.

Fourteen hours after the alarm sounded, the fire is out. But the explosion damaged or destroyed all of the ship’s systems. Except for a few containers of distilled water — enough for seven days — we have no drinking water. The sewage system isn’t working. We have no heat or electricity either, except the dim emergency lighting. The explosion destroyed the main engine and damaged the small engine.

Rescue is not possible. The closest icebreaker is on its way to be dry-docked in Seattle.

We will have to rescue ourselves.

~~

The cold creeping in from outside drops the temperature inside the ship to the mid-40s. Those of us who didn’t dress appropriately before put on warmer clothes. Looking like a bunch of fat red penguins in freezer suits, hats, and gloves, the scientists and staff organize into crews. One crew repairs the pipes that freeze and burst. Another mops up spills to prevent electrical fires.

Without a functioning galley, cereal and sandwiches become our mainstay. The penguin researcher donates her two tiny gas stoves, which are enough to make two big pots of soup.

More than a thousand miles away in Hobart, the general manager of P&O issues a press release to the news media and our families. It says that there was a small fire on the ship, but everyone on board is fine. We’re not in danger. The ship is on its way back to Hobart.

Of course, the fire wasn’t small. We are still in danger. And we’re not on our way back to Hobart. We’re stuck in the middle of the ice pack.

Then the GM orders the captain to lock down communication from anyone on the ship to the outside world.

Antarctic sea ice in early spring fissures from the unquiet ocean beneath it. Photo: Stocktrek Images / Alamy.

~~

His lips touch my ear. “If you tell anyone,” he whispers, “your mother will die.”

My mother is my lifeline. Even though it’s a tattered lifeline, if it disappears — if she dies — I will die.

~~

The blizzard we expected roars in. During occasional lulls, we take breaks on deck for snowball fights. Two scientists build a snowman, and I make it anatomically correct by adding a penis and scrota. I think it’s funny as I’m adding the genitalia, but once inside, I gaze at the snowman and can’t figure out why I did such a thing. A day later I kick off the appendages.

Thirty hours after the fire, the venting is complete. The engineers, crew, and techs recruited from the science group are working to jury-rig the ship’s systems. Miraculously, they get us hot-water showers and a functioning sewage system. But every other system — including the heat and the ship’s stabilizers — is dead.

We all pitch in to fix meals and clean up, take turns sweeping and mopping the companionways and rec rooms, assist the 24-hour-a-day burst-pipes crew, and keep a close eye on one another, lending support when fear overwhelms.

Their flashlights reveal strands of smoldering cables hanging like old spiderwebs, frayed and melted wires sagging on control panels.

Everyone is anxious to communicate with the outside world. While outgoing email is banned, incoming messages pepper our inboxes and grow increasingly frantic. My editor at Discovery Channel fires off questions every few hours: “We heard about the fire. I’m glad everything’s OK now.” “Why haven’t I heard from you?” “Why aren’t you filing?” and finally escalating to “Where’s your story?”

We had agreed with the captain’s request for an email embargo until the emergency passed. But now that it has, the engineers deliver an ultimatum: Lift the email ban or we stop work. The captain acquiesces, knowing that he’ll catch hell from the general manager.

I finally send out a chronicle of the past two days to the Discovery Channel. In the U.S. our dilemma is big news only in scientific circles. But Australian reporters seize upon my story. After P&O’s false media release, they flood the general manager with requests for access to the ship’s captain or chief scientist. The general manager refuses, and they conclude that he’s hiding something. Suddenly the plight of the Aurora Australis is that nation’s biggest story.

The general manager tries to shut me down. He’s seen my first dispatch, with its accompanying photos of Dali-like melted lights and charred equipment, and complains to the captain that I’m revealing the ship’s secrets. I point out that photos of the ship and its schematics are already on the Australia Antarctic Divisions’s website, which the media have used in their articles, and by now the people onboard have emailed their families, so it’s no secret that there was a fire aboard ship.

The world knows the truth about our situation, and there’s no use trying to backpedal. The captain and the chief scientist wearily agree.

To keep a certain peace, I offer to let them review the next story before I send it out. But if they take a heavy hand to my copy, I’ll let my editor know so that she can put a “censored” tag at the top of the story.

The chief scientist asks me to remove only the names of the stewards who were so drunk that they didn’t hear the fire alarm, and I agree. But the situation turns my stomach. It doesn’t occur to me to complain to my editor at the Discovery Channel. I don’t know why.

I just ride this out alone, as I always have.

~~

Three days after the explosion the engineers are ready to test repairs to the small engine, which was partly damaged by the fire. We anxiously gather outside the bridge. The engine starts, catches, and purrs.

We expect the captain to shut it down to do a few more tests, as he’d planned, but he shouts to the engineer, “Don’t turn it off!” and orders the officer on deck to turn the ship 180 degrees. We cheer, and like a horse making for the barn, the ship starts breaking ice as it heads straight for port.

The engineers tell us just how lucky we’ve been. The cause of the fire, they’ve determined, was a broken fuel line. If it had ruptured two days earlier, while we were rolling through 15-foot waves, fuel would have sloshed back and forth, destroying the second engine as well. Crew would have died or been injured, and with very little morphine on the ship, they would have suffered terribly.

If the line had ruptured one day later, we would have emerged from below deck into a blizzard with 60-knot winds and a wind chill as low as minus 58 F.

And if we’d been in the thickest sea ice instead of in two- to three-foot-thick ice, the ship could have become stuck or been crushed.

As we finally leave the ice behind and move into open water, the chief scientist and the deputy scientist tell me one more thing. Thanks to my flashlight, the attendance rolls were called quickly enough that the captain was able to release the halon gas just in time. Another eight seconds, they say, and the safety caps on the liquified-natural-gas canisters would have melted completely.

The ship would have blown up.

“You saved our lives,” says the deputy chief scientist.

~~

We know we’re near civilization when planes begin flying low and slow overhead — news photographers taking photos and video. Finally, on July 31, the Aurora Australis limps into a windy and heaving Storm Bay.

The P&O general manager has ordered the ship to dock before dawn, in hopes that the early hour will mean few reporters and little media coverage. At 4 a.m. we’re cleared to approach Princes Wharf.

To our surprise, hundreds of people crowd the long cement dock: mothers, fathers, husbands, wives, children, friends, dogs, and reporters shining bright lights on everyone as they record our arrival. People yell and wave banners and flags. The expeditioners, some with tears streaming down their faces, yell and wave back.

As soon as the gangway touches the wharf, the general manager strides up the steps, a threatening scowl on his face.

It’s the first time I’ve laid eyes on the man. First impression: square, bearded, humorless, ruthless. As the crew members roll down the banner, he shoves them aside with his elbows. Everyone on the ship and on the dock goes silent.

In the general manager’s wake are two people wearing suits and carrying briefcases, heads hanging in embarrassment. As the three disappear into the ship, the expeditioners run down the gangway into the arms of their families and friends. Gleeful pandemonium erupts on the dock.

~~

I walk to my hotel room. Exhausted, I drop my bag on the floor. Fully clothed, I roll up in all the blankets and drop into sleep the way I’d fall off a cliff.

The darkness seems to shift. Something colder, blacker, and quieter than the night surrounds us.

A little while later, my heart pounding, I thrash to escape the blankets that imprison me, and am thrown into a flashback.

Now I’m a seven-year-old waking up naked in a bathtub of freezing water in the middle of the night. Beneath me, tangled up in my legs, are my soaked bedsheets. The cold water runs full force from the faucet as I struggle to get out.

My parents lean over the bathtub, their faces angry. They push me back into the water and yell, “This will teach you not to wet your bed!”

It’s not that I’d ever forgotten the experience. But this is the first time I’ve felt it — felt unrelenting rage, despair, and helpless shame that squeeze the breath out of me.

I get out of bed to walk in circles. The dream and the memory and the feelings wash over me and through me. I feel as if I’m drowning.

I have no idea where these feelings come from, or what to do with them.

~~

I take a shower and head back to the ship for the press conference.

Reporters jam the bridge. The captain and the chief scientist stand side by side.

Lurking behind them, the general manager studiously ignores me, even when I move to his side. He keeps his face neutral, but his eyes bore into the back of the captain’s head while reporters fire questions.

The captain and chief scientist answer cheerily, perfunctorily, tiptoeing around questions about how the fire occurred and steering most of their answers to how fortunate it was that no one was injured and how good it is to be home.

It’s a happy occasion, but I can’t shake a feeling of betrayal. They don’t mention how close we came to dying. Or that a frayed fuel line that hadn’t been inspected properly set off the fire. Or any of the other problems we faced.

~~

I don’t know how much she knows about the night visits when I was seven, but I do know that she walked in on him as he suddenly stuck his fingers in my vagina when I was 16, on the pretense of massaging a painful cramp out of my leg. As I was trying to get away, she turned and walked out of the room.

I buried my deep rage at her betrayal and, instead, turned the fury on myself.

~~

At the press conference I step behind the general manager. He’s considerably more upset than his face shows. He wrings his hands so tightly that it looks as if his fingers will twist off.

Two days later, I will be sitting on a bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean in California. Eight thousand miles away in Hobart, the general manager will drop dead of a heart attack.

~~

The ocean looks serene at a distance. But at the base of the bluff, wave after thunderous wave pile detritus onto the rocks as the Antarctic voyage and near-death experience trigger flashbacks from my childhood — waves of memories that leave me pummeled and disoriented for weeks.

When I was 17 my stepfather called me into the bathroom, where I found him, my mother, and my toddler half-siblings nude in the bathtub. He invited me to join them. My mother stared blankly into the wall. Feeling nauseous, I walked out without a word.

On a visit home from college a year later, I was thinking about how to moderate my drinking at parties and wondered aloud how many drinks it would take to get drunk. My stepfather suggested we find out. When I began slurring my words, he asked if he could show me how to masturbate. I vomited.

When I was in my 40s, at the Thanksgiving dinner table, he joked about me shedding my clothes, jumping in my brother’s pool, and running naked down a public street.

Some of these memories have always been there, but the experiences aboard the ship have triggered more — and coalesced them into a storm of fear, rage, sorrow, betrayal, shame, and loss.

It takes nine months for the Aurora Australis to be repaired and head out on another voyage. My repair takes years, and leaves me in a completely unexpected place.

A few months after leaving Antarctica, I ditch the fiction that I grew up in a normal and loving family — and that someday my stepfather and mother would admit their guilt and apologize. I write a letter to them about my experiences with my stepfather. They cut off all communications and disown me; I expect it.

Therapy has been a lifesaver, but it has left me feeling incomplete.

~~

No one seems to breathe as we eavesdrop on our future.

Bestsellers about sexual abuse, alcoholism, and depression proliferate. Tens of thousands of “anonymous” groups provide solace for people wrestling with all kinds of addictions. But no books or support groups had relieved me of the notion that the abuse I endured was my fault.

That there was something wrong with me. That I was bad. That I was too sexy — at seven years old! — and he couldn’t help himself. That I asked for it.

Finally, though, something flipped my life trajectory and healed me: science.

As a science journalist, it’s corny to say that. But that’s what happened.

Not all at once, however.

~~

Journalists are a suspicious lot; that’s our job. So when I heard about some wonky-sounding research called the ACE Study, I thought, Somebody’s making this up.

Somebody’s making up that adversity in childhood leads to the adult onset of most chronic diseases and mental illnesses, and is at the root of violent behavior, whether by a perpetrator or a victim.

Somebody’s making up the finding that most people have one or more of the 10 adverse childhood experiences that were measured in the study. And that if you have four “ACEs,” your likelihood of becoming an alcoholic increases 700% compared with people who have an “ACE score” of zero. And that your likelihood of attempting suicide increases 1,200%. And that your risk of a heart attack doubles and of lung cancer triples.

But it’s real.

The first of the 70 research papers from the CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences Study was published in 1998, two months before I boarded the Aurora Australis. I wrote my first article about the link between obesity and ACEs in 2005.

But there was one piece of research that compelled me to leave a solid career as an online news executive. It was the 2009 finding that people with six or more of the 10 ACEs in the original study — including abuse and neglect — are at a higher risk of dying 20 years prematurely than people with zero ACEs.

That’s me: seven ACEs.

“In my beginning is my end.” — T.S. Eliot

~~

Everyone needs to know about this, I think. I launch a news site and social-media network in 2012, just as researchers begin adding other ACEs, such as racism and community violence, and connecting the dots between ACEs and how they cause toxic stress in our bodies and brains that leads to bad behavior and disease.

Over the next several years I give hundreds of talks about ACEs science. I tell people how our human brains and bodies respond to being blamed, shamed, and punished by creating toxic stress and using unwanted, unhealthy, or criminal behavior to cope. The most common response: “This explains my life! I’m not crazy! Why didn’t someone tell me about this sooner?”

But if our secrets are acknowledged and we understand that the way we coped with what happened to us was normal — not crazy — we can heal.

~~

Understanding the science of positive and adverse childhood experiences rescued me. It not only helped me understand my ACEs and how I responded to them; it also helped me understand my parents’ ACEs and how, unwittingly, they passed them on to me.

My stepfather was sexually abused by a priest when he was four. My mother was sexually abused by her father and left home when she was 16.

In time I release my anger at them, and eventually at myself.

~~

Twenty-four years ago, on the plane ride from Tasmania back to California, I thought my Antarctic journey had ended. I was ready to move on, to report on a new adventure. But then I was abruptly heaved into this unexpected odyssey.

I have absolutely no regrets about that trip to Antarctica, despite the gremlins’ warnings. It opened a path to healing that my body and mind had longed for from the time I was a child — but that was invisible to my adult consciousness.

All the courage and fortitude I mustered to survive the voyage aboard the RSV Aurora Australis has since carried me forward, even when I didn’t know where I was going.

In my near-ending was my beginning.

The bow of the Aurora Australis breaks through frigid Antarctic ice waters. Photo: Fred Olivier / Alamy.

Jane Ellen Stevens

Jane Ellen Stevens — a longtime health, science, and technology journalist — is the founder and publisher of PACEs Connection (PACEs = positive and adverse childhood experiences), which includes the news site ACEsTooHigh.com and the social network PACEsConnection.com.

Never miss a story

Subscribe for new issue alerts.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive updates from Hidden Compass regarding new issues and other ongoing promotions such as workshop opportunities. Please refer to our Privacy Policy for more information.