Support Hidden Compass

We stand for journalism, science, history, and hope. Make a contribution to Hidden Compass and stand with us.

This story has been republished in the Hidden Compass Legacy Issue in celebration of reaching 100,000 readers.

Gazing out over an uneven checkerboard of green marshes and high-tide swells, I feel quiet and grounded. Flecks of Kelly-green wild grasses and golden-brown cattails enliven ribbons of slate-blue water. The tidal wetlands of Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge off Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay hold secrets.

Blackwater is still. I glide on a watercolor palette in the setting sun, dipping my paddle into a patchwork sea of peony pinks, magentas, and dusky blues. The bow of my boat cuts through a decrescendo of gold gouache ripples. Everything is moving, yet everything has stopped. It could be 1855.

A great blue heron emits a series of croaking cries. But the past, murkier than the marshland, cries louder. The seasons and tides flow in reverse, past the marches of the 1960s, the Jim Crow laws of the 1920s, the Civil War of the 1860s — all the way back to about 1820, when a baby named Araminta Ross was born with a destiny none could have foreseen.

~~

Wade in the water,

Wade in the water children.

Wade in the water.

God’s gonna trouble the water.

~~

As I rock on the water and gaze at the low, late-August sun, my mind wanders the history of this coastal maze. One hundred and sixty years ago, Harriet Tubman plied these waters as she led her people to liberty. Born in 1820 as Araminta Ross, enslaved off the Chesapeake Bay in Dorchester County, Maryland, she eventually took her freedom by slipping across the Mason-Dixon line. Known as the “Moses of her people,” Tubman returned to the Eastern Shore of Maryland more than 15 times to lead others to liberation. Now, these waters and woods bear her name.

Perhaps it was a day like this humid summer one that envelops me with a deafening orchestra of cicadas, when, with sweat beading on her brow and breath bursting from her lungs, Harriet Tubman parted a curtain of cattails, making her move for freedom. Perhaps the sky was an expansive yet almost-touchable purple-pink when she asserted her humanity and her personhood. Perhaps, like now, a hot red sun hung low in the sky on the day when she escaped slavery forever.

Painting: Latasha Dunston Greene

~~

Who’s that young girl dressed in red?

Wade in the water.

Must be the children that Moses led.

God’s gonna trouble the water …

~~

One-quarter of my own family line comes from St. Mary’s County, about 20 miles from here as the crow flies across the warm, muddy-brown Chesapeake Bay. For the past 10 years, I have spent considerable time researching my family tree. For all the challenges that normally come from this pursuit, it’s doubly difficult because my ancestors were enslaved.

For many, it’s a source of joy to read the stories of one’s people, to see the heirlooms, to feel the strength of forebears. But while I feel kinship and pride, I am disheartened to see how little information exists. I feel a gnawing in my stomach when I see the birthdates, places, people, and families that were erased, forgotten, or never recorded. Such documentation was deemed unimportant for people who, treated like machinery, powered the economic engine of the early United States.

Enslavement isn’t just about the body: It’s about attempting to remove control of the mind by subjugating stories, narrative, culture, faith, family.

The little information I have found about my ancestors has led me to an estimated birth year here or a detail there. Enslavement clung to the few recorded details of their lives: Name; Race; Potential cause of death; Post-Civil War job or occupation. In antebellum coastal Maryland, an ancestor of mine was a sharecropper, another an oysterman — industries that re-hung the shadows of slavery for black Americans.

With little information, it’s hard to know what to say about the people who came before us. That’s the brilliance of those who benefitted from and perpetrated the trade of enslaved peoples. Enslavement isn’t just about the body: It’s about attempting to remove control of the mind by subjugating stories, narrative, culture, faith, family.

With little information, we do what we can to honor their lives.

~~

See that band all dressed in white?

God’s gonna trouble the water.

It look like a band of the Israelites

God’s gonna trouble the water.

~~

Spirituals such as “Wade in the Water” are believed to have served as coded instructions to help people navigate the Underground Railroad and safely reach freedom in the North. Another spiritual, “Follow the Drinking Gourd,” likens the gourds used by enslaved persons for drinking water to the Big Dipper, and was used as another code to instruct freedom seekers to follow the Big Dipper, which points to the North Star.

The calm wetland waters cradled these freedom seekers — it washed away their tracks, diluted hounds’ abilities to catch their scent, and provided them a map as they headed north. The ever-present water was there to cleanse sweat from their brows as they laboriously navigated the coast. In a time of life or death, maybe they looked over the waters as I do — the last of the sunlight dipping below the horizon — and felt a moment of calm. Maybe the coolness of the water kept them awake and alert as they slipped noiselessly through the tides and marsh grasses.

When they needed strength to keep going, this abundant sanctuary was rich with plant and animal life that provided them with nourishment — just as the spirituals of their ancestors gave them wisdom.

~~

Follow the drinkin’ gourd

For the old man is comin’ just to carry you to freedom

Follow the drinkin’ gourd

When the sun comes back, and the first quail calls

Follow the drinkin’ gourd

~~

Perhaps it was a warm spring South Carolina night in May 1862 when the water beckoned with the promise of safety and serenity to Robert Smalls, an enslaved man in South Carolina and an ancestor of mine. Perhaps he remembered the lyrics to these spirituals that early morning when the Confederate soldiers took shore leave from the ship The Planter, leaving Smalls and several others to consider the unthinkable.

It was a tremendous risk to even consider escape, let alone actually attempt it. If he failed, Smalls would face violent, if not deadly, punishment. But if he succeeded …

Acting quickly, 22-year-old Smalls (a vessels expert wheelman) donned a Confederate uniform, commandeered The Planter, and sailed out into the sea, directly toward the Union blockade. Detection and death were probable, but the chance of freedom was palpable to Smalls.

~~

Well the riverbank makes a mighty good road

Dead trees will show you the way

Left foot, peg foot, travelin’ on

Follow the drinkin’ gourd

~~

Water surrounds. Even the breeze here is heavy with water. Suspended in the thick and humid air, it quenches the verdant coastal forests. Hugging the shoreline, it licks the sandy brink. Here, in this clammy, subtropical climate, it supports life.

On the other side of the world, in what is now modern-day Benin and Nigeria, practitioners of the Yoruba religion believe in Oshun, a goddess of the sweet waters, love, and the benevolent protector of the poor and needy. In West, Central, and Southern Africa, “Mami Wata,” or “Mother Water,” appears in a variety of roles in an equally wide range of narratives. Her worship is well-documented not only in Africa, but also in the African diaspora, particularly in the Americas and Caribbean. Depicted as a mermaid, mentions of her likeness trace the paths of former slave routes.

~~

For the old man is waiting to carry you to freedom

Follow the drinkin’ gourd

Well the river ends, between two hills

Follow the drinkin’ gourd

~~

Benin, West Africa: the epicenter of the slave trade. At its heart, the Road of No Return: a dusty, red road that led to the Atlantic Ocean where, chained together by the 600, men, women, and children boarded ships, never to be seen again. The last ship set sail in 1860.

The Middle Passage: For every 100 enslaved people who reached the “New World,” around 40 died. So many Black Americans’ roots are planted in the clay red soil, including my own.

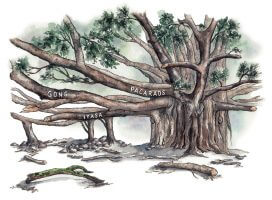

After capturing their victims in West Africa, Dahomey raiders conducted a forced ceremony for the newly enslaved persons — a ceremony that symbolized the beginning of their forgetting. Seven to nine times, Dahomey raiders directed enslaved men and women to circle around L’Arbre de L’Oubli — The Tree of Forgetting. Their enslavement began with the loss of what came before: Their homes. Their culture. Their family. Their roots. Themselves.

~~

There’s another river on the other side

Follow the drinkin’ gourd

For the old man is waiting to carry you to freedom

Follow the drinkin’ gourd

Painting: Latasha Dunston Greene

~~

During the raids, there were those who sought safety on the water.

In the small village of Ganvie, a community that still thrives today, thatched homes and businesses mounted on stilts are perched on top of the brown, brackish water. On Lake Nokoué, just outside of Benin’s capital of Cotonou, this village has stood and grown since its inception hundreds of years ago. Life runs suspended above the water. Mile-long stretches of intricate netting allow residents to farm fish, while centralized water filtration systems provide potable water fetched daily by families in canoes throughout the village. Schools, places of business, and markets stand alongside people’s homes.

The community was the idea of the Tofinu tribe’s king. To avoid being captured and sold into slavery to the Portuguese by Dahomey raiders, the king took his people to the water and built a self-sustaining home over the lake. Although the physical barriers keeping them safe were few, Dahomey religious practices and customs held that a people who lived on the water could not be attacked. And so, water kept the Tofinu safe.

~~

When Israel was in Egypt’s land

Let my people go

Oppress’d so hard they could not stand

Let my people go

Go down, Moses

Way down in Egypt’s land

Tell old Pharaoh

Let my people go.

~~

By the middle of the 18th century, acres upon acres of land in Georgia and South Carolina Low Country, as well as the Sea Islands, had been turned into rice fields. Wealthy plantation owners placed farmers taken from the “Rice Coast” of Africa onto these islands to cultivate fields in unfavorable conditions. Hacking through cores of tall, scraggly deciduous trees, mantles of arching and bowing palms, and bleached, gracefully gnarled driftwood, these expert West African cultivators transformed the landscape into fertile rice fields. Through back-breaking labor and hellish living conditions, they made a fortune for the few people in power: An enslaved person growing rice could generate more than six times his or her original purchase price in just one year.

These Gullah communities still live on South Carolina’s coastal plains and Sea Islands. They were the home of Smalls’ mother Lydia, until she was taken at nine years old. Three of my four family lines also grow from here, in coastal South Carolina.

Here on the Sea Islands, the water cradled the West African farmers in a sacred semi-isolation. As malaria and yellow fever spread, non-Africans often left the rice fields (with maybe one or two people left behind during the spring and summer months). Despite the heavy toll on the community with many lost to these diseases, the region and the people were culturally freer and able to create and maintain some sense of their collective heritage.

They had the freedom to dictate a portion of how they would live their lives and tell their stories. In defiance of the ceremony of L’Arbre de L’Oubli, of their capture, and their separation from their family and home, they joined those around them and created a new culture from many.

Despite being uprooted from their homes, they thrived where they were planted.

~~

Well, where the great big river meets the little river

Follow the drinkin’ gourd

The old man is waiting to carry you to freedom

Follow the drinkin’ gourd

~~

At 2 a.m., Smalls put on the straw hat of the vessel’s captain, then stopped at a wharf to pick up his wife and children as well as several others.

At 3:25 a.m. The Planter surged forward, slicing through Atlantic waters. Passing by other Confederate ships, Smalls flashed the correct naval signals to gain safe passage through the fleet that was tightly protecting Charleston and Sumter. It was just dark enough that he was mistaken several times for the captain of the ship.

I imagine how the sense of relief, the weight of what some called a foolhardy escape, and his family’s newfound freedom came crashing down on him as the clear blue South Carolina waters surrounded Smalls near the Union blockade.

It was only once The Planter was out of range, as the sun began to rise in the sky, that he dared hoist a bedsheet brought on board by his wife. I imagine that there was barely enough light for Union ships to see the white flag, held high above a ship full of people fleeing slavery.

I imagine how the sense of relief, the weight of what some called a foolhardy escape, and his family’s newfound freedom came crashing down on him as the clear blue South Carolina waters surrounded Smalls near the Union blockade. Against all odds, he had found an oasis of security next to a hotbed of hostility. His pulse pounding in his ears must have deafened the commotion around him. The scene unfolding before his eyes must have moved in slow motion, as if he was underwater. He must have felt as if he was watching himself in an undeniably surreal situation. Is it real? Is it happening? Are we safe?

For generations, my family has named children after Robert in honor of his bravery, sagacity, and spirit. Although a mere seven miles of turquoise ocean lay between him and life as a free man, it must have felt to him and those on board like the length of the Atlantic.

~~

For the old man is waiting to carry you to freedom

Follow the drinkin’ gourd

For the old man is waiting to just to carry you to freedom

If you follow the drinkin’ gourd.

~~

The wisdom of these lyrics urging my people to stay close to the water is rooted in something older and stronger than the thousands of vessels, unimaginable manpower, and unmistakable greed that created and sustained the Transatlantic slave trade. Enslavement was meant to define and overpower my people, but they resisted. Like the water that surrounded them, they carried on with strength, stalwart consistency, and beauty.

I think of Robert Smalls, known as “The Gullah Statesman” for his pride in the heritage of the West African people who thrived on the coastal plains and Sea Islands. Even while under his former masters’ command, he wisely learned to navigate these coastal waters. He waited until the clear bright Atlantic was ready to extend the hand of freedom. When the water called, he was ready.

I think of Harriet Tubman. She planned, plotted, laughed, cried, loved, succeeded, failed, and had virtues and vices — she lived as a human being. To take her freedom, Harriet, a new Moses, parted the waters not with a rod or staff, but with the deliberate footsteps of a woman bound for the Promised Land on the other side of the Chesapeake Bay.

I think of L’Arbre de L’Oubli, the Dahomey raiders, the perilous Middle Passage across the Atlantic, the subjugation of generations of people, the loss, the pain, the fear, and finally — the survival. The remembrance. The wisdom that was passed down, against all odds.

Because of those who came before, I’m here to remember, to share their stories and to proudly live my own.

As I sit in my boat watching the last drops of golden day slip beyond an inky horizon, I follow the people — my people — who came before me, and wade in the water.

If you don’t believe I’ve been redeemed

God’s a-going to trouble the water

Just follow me down to the Jordan’s stream

God’s a-going to trouble the water.

###

In the years since I published this story, I’ve continued to share the stories of my ancestors — and my own.

Illustrator Latasha Dunston Greene is a Baltimore native, turned Denver transplant. She is an artist and outdoor enthusiast with a love for sharing the curiosity of adventure and inspiring folks to seek out their creative side. She works mainly in watercolor and ink but enjoys digital drawing as well. When she isn’t in her studio she is romping around in the desert, or mountains, or taking long drives to new places with her mini dachshund right by her side. You can keep up with her adventures and creative process on Instagram @jitterbug_art. To view galleries of artwork, including ink drawings, watercolor paintings, and murals, visit her website http://www.jitterbugart.com.

Alexandria Scott

Alexandria is a writer, educator, and community advocate.

Never miss a story

Subscribe for new issue alerts.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive updates from Hidden Compass regarding new issues and other ongoing promotions such as workshop opportunities. Please refer to our Privacy Policy for more information.