Support Hidden Compass

We stand for journalism, science, history, and hope. Make a contribution to Hidden Compass and stand with us.

The rainforests of Sumatra rise on either side of the Bohorok River. Photo: Hayli Nicole.

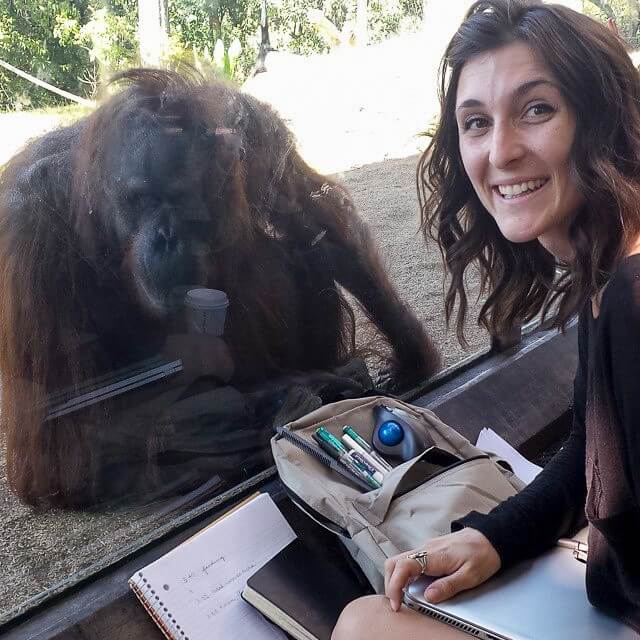

San Diego, 2013

She came over uninvited to where I was sitting. I had been in the same spot all afternoon, logging my observations for class. My clipboard sat in my lap, and my backpack was slightly open in front of me. She scratched her head with a look of curiosity. Was she finally seeing me, as I was seeing her?

An unknown voice chimed in, “She wants to see what’s in your purse.” An older woman in a red shirt was leaning slightly over me. “Go on,” she assured, “she loves brushes. And lipstick if you have it.”

Reluctantly, I pulled out the contents of my bag — first, a binder. Then, a book. A couple of pens quickly followed. I drew a line on a blank piece of paper that seemed to have piqued her interest. I scribbled illegibly for my new friend to see, but boredom quickly flashed across her face.

Remembering the woman’s comment, I reached for my cosmetics bag. Suddenly, I had her undivided attention. I opened a tube of lip balm and closed the cap. Over and over and over again. She tickled the window with her fingers, as if to encourage the repetitive motion. I ran a comb through my hair. She ran her fingers through hers. I dragged a makeup brush over her nose on the glass between us. She followed the sweeping motion with her eyes. She eventually placed her forehead on the window, inquiring further about the contents of my bag. I reached for my compact mirror. I turned it around for her to see her image. She turned her head to reveal each of her cheeks, her gaze locked on the round reflection. She knew the deep brown eyes staring back at her in the mirror were her own.

Her name was Janey.

Sumatra, 2019

I pull myself higher by the exposed roots of the tree towering over me. I notice this particular trunk is being swallowed by a ficus growing towards the earth rather than away from it. Dozens of limbs contort around the tree before sprawling in the slick gold clay. To keep myself from slipping, I hook the heels of my boots into small pockets made by the tangle of tree roots. My feet are moving, but it doesn’t feel like I am gaining any elevation.

Last night’s rain left rock faces slippery and the earth unstable. My knees and boots are caked in mud from a few missteps. Looking down, I notice the fresh blood that has stained the heel of my sock. Monsoon season makes trekking a full-body affair, but it also brings leeches out en masse. As quickly as I am climbing, I am also scrambling to avoid what is hiding amongst the fallen leaves, waiting to latch on to the next creature passing through the ferns.

When I reach the ridge, my chest is heaving. Sweat drips from every crevice of my body and I wipe myself with clothes still damp from yesterday’s perspiration. I unhook my boots and peel off my socks inspecting for uninvited critters. My fear is confirmed when I find a leech, already swollen from its feast, on my Achilles. I pluck it from my leg and curse its existence, noting the blood staining my socks.

Our guide, Kinol, scans the canopy. I am there with my dear friend Sydney and a man we befriended last month sailing somewhere between Flores and the Komodo Islands. We all silence our voices and steady our breathing long enough to listen. Siamang calls echo from a distant ridgeline. The great Argus pheasant lets out a distinct whooping for its mate. Somewhere macaques quarrel, but it is hard to distinguish where over the constant humming of the cicadas.

A butterfly rests on Kinol’s finger as he takes a break from guiding author Hayli Nicole through the Sumatran rainforest. Photo: Hayli Nicole.

We find an abandoned sleep nest close to where we stand. The faded orange of the gathered leaves tells us the nest is several days old. The leaves are folded into each other with precision — packed tightly in a frame of snapped branches and twigs. A swell of excitement distracts from the exhaustion weighing heavy on my bones because this can only mean one thing: an orangutan found refuge along this same ridge.

Kinol finally disrupts the silence, “We take break here.”

“Okay,” we reply, still out of breath, checking for anthills before dropping our packs and our bodies to the earth.

Snack time is a spread of bananas, oranges, and halves of passion fruit. Kinol effortlessly cuts a pineapple in four. We dig into the sticky goodness, slurping our way through the juices of the fleshy, sweet interior. Our clothes smell like a mix of sweat, mold, earth, and tropical fruits.

We are on day three of our six-day trek in Gunung Leuser National Park in Northern Sumatra. This is my third time in the rainforest. I first arrived in 2015 for orangutan conservation research; back then, I’d planned to move here. It hadn’t quite worked out that way, but I’d been drawn back to the rainforest in 2018 and again now, both times searching for clarity and connection following events in my personal life. The rainforest always seems to know what I need, even when I don’t. My love for this place had been an easy sell to my friends who now joined me on my quest to see orangutans in the wild.

Wildlife encounters are never guaranteed on a trek like this, but we’ve been spoiled. Yesterday it was a pig-tailed macaque munching on discarded fruit.

A pig-tailed macaque checks its surroundings in the rainforest. Photo: Hayli Nicole.

The day before, it was the ladies of the semi-wild orangutan population all vying for the attention of the alpha male.

A semi-wild alpha male orangutan. As they become used to humans, some wild orangutans give up foraging in the wilderness for the easy pickings of human food. Photo: Hayli Nicole.

So far, though, there have been no wild orangutans. But quite frankly, we’re simply overjoyed to be covered in this much filth.

~~

Bukit Lawang is a village bordering Gunung National Park. The rainforest towers in every direction, and guesthouses mirroring the natural environment promise unforgettable views of the endless greenery. It’s a place where gardens flourish and rain’s greatest bounty is the constant availability of fruit. Troops of macaques scour the rocks for remnants of fish caught by villagers. The river never loses its momentum, and the impenetrable wall of trees keeps your mind wondering — What else is in there?

It’s an important question.

The village of Bukit Lawang is built on the Bohorok River. Bridges connect the village to Gunung Leuser National Park. Photo: Hayli Nicole.

In 2015, I was a volunteer with an organization researching the self-medicating behaviors of wild orangutan populations. Fecal and urine analysis had identified several parasites as well as potential correlations to medicinal plants found in orangutan diets. In November 2017, the lead researcher published findings from an orangutan population in Borneo that showed the use of chewed leaves as a topical application for inflammation — the leaves came from the same plant that indigenous populations used to treat their own ailments.

The findings were remarkable enough, but they coincided with something even more remarkable: The confirmation of a new species of orangutan on Sumatra. The Tapanuli orangutan, Pongo tapanuliensis, was confirmed and announced in the same month. But the discovery was cause for both amazement and concern. According to research and data published in Current Biology, less than 800 individuals exist in the wild, making it the most threatened of all the great ape species.

From the first sighting in 1997, it was 20 years before a cranial analysis of male remains and additional observations confirmed the existence of the third species of orangutan. In almost the same 20-year span, between 1999 and 2015, more than 100,000 Bornean orangutans were lost due to hunting, deforestation, and habitat destruction for palm oil plantations. That means half of the population on Borneo was eliminated in the time it took for a separate species to be discovered in Sumatra.

A rehabilitated orangutan visits author Hayli Nicole’s camp, waiting to forage for discarded food scraps. The orangutan’s infant keeps a safe distance, building sleep nests and exploring the canopy. In the wild, orangutans have been observed using medicinal plants to treat their own ailments. Photo: Hayli Nicole.

~~

I’d hoped the simultaneous discoveries would be enough motivation to protect the rainforest from rampant deforestation, but two years later, when I arrive in Medan, the capital of North Sumatra, the air is dense and suffocating with toxicity. Acrid smoke fills the skies from fires in southern Sumatra and neighboring Borneo — slash-and-burn clearings for palm oil plantations. Flights are canceled in airports as far north as Malaysia. Motorists wear respirator masks to protect their lungs. But the heaviness is felt in each breath. The fires are thousands of kilometers away, yet the heat burns in my chest as if I am inhaling the flames.

The four-hour drive from Medan to Bukit Lawang means staring out the window at hectares upon hectares upon hectares of palm oil plantations spanning to the left and right of the two-lane road. Their perfectly straight lines, with nothing but ferns growing between them, is a reminder of how unnatural their presence is. Our driver dodges potholes created from oversized trucks hauling palm kerns from remote villages to processing centers. Farmers have forfeited their familial plots for a quick payout from palm oil corporations without realizing the land will be starved of all nutrients, rendering it useless for future cropping. The global demand and export of this monocrop has single-handedly waged war on, and contributed to the destruction of the rainforest, while threatening the livelihood of communities so reliant on the rainforest’s existence.

The journey leaves me reeling, but as the hills of the national park break along the horizon, revealing the first glimpse of the rainforest, a flutter of anticipation fills my stomach like butterflies in the whirl of a hurricane. The impressions carried from previous treks flood to the surface, escaping my body through falling tears. Finally reaching Bukit Lawang means returning to a place that shaped my life and an opportunity to reunite with a species I consider to be a physical extension of my heart.

San Diego, 2013

There was nothing left in my bag. I watched as Janey stood slowly, clearly arthritic. At 50-years-old, she was more elderly than most orangutans in the wild. I watched her cross the hill of the exhibit, knuckle after knuckle until she was out of sight. A million questions whirled as I thought about our encounter: Did that happen? Has anyone else experienced this? Did she recognize herself, or is that me anthropomorphizing? What do I have to do, to do something like this every day for the rest of my life?

For the next three years, I spent every Wednesday with Janey at the San Diego Zoo. Some days we would engage for five minutes. Others, we would sit together for hours in the corner of the exhibit while hundreds of people walked by. Sometimes, I would find Janey slowly pacing in front of the rocks leading to her sleeping quarters, waiting for the keeper to let her in for the night. Others, I would find her lying in the shade by the exhibit moat, staring into the sky, her hands tucked behind her head and her ankle resting across the opposite knee. On days like those I was content with no interactions at all.

Orangutan means “people of the forest” in Bahasa, and after witnessing Janey’s humanness, I finally understood why.

Sumatra, 2018

I never understood the word fleeting until my encounters with wild orangutans. Their movements are swift, silent, and calculated, making them almost undetectable to the untrained observer. Trekking guides use a combination of grunts and kiss squeaks to mimic the orangutan’s natural modes of communication. If their approach fails to coerce an audible response, sleep nests are the next indication of being in proximity to an individual. Orangutans are solitary by nature, rarely spending time in groups unless it’s a child remaining close to its mother. With less than 7,000 Sumatran Orangutans remaining, a single sighting is like winning the jungle lottery.

On my 2018 trek with Kinol, I’d won that lottery. We were a group of 10, not including the porters and assistant guides. Despite our efforts, the commotion of 10 bodies thrashing through foliage and the echoes of competing voices meant we were heard long before we arrived anywhere. I became frustrated by the constant noise we were creating, so Kinol, myself, and my friend Jess intentionally fell behind while the rest of the group plowed through the final miles to camp.

Kinol’s mantra is, walk slowly, see more, so walk slowly we did. We climbed vines thicker than our torsos. We stopped to smell mushrooms to see if they were poisonous. We sat on thick roots passing a water bottle between us, taking as many breathers as we wanted on our way down. It was easier to keep our eyes on the tree line without worrying about the footing of others behind us.

An infant clings to her mother, cautiously observing the trekking groups gathering below. When not at rest, like these two, orangutans move through the canopy swiftly and silently. Photo: Hayli Nicole.

We were 30 minutes from camp when there was a loud commotion in the tree directly above me. At first glance, I couldn’t see the culprit, but when my eyes adjusted, I saw distinct red hair. Jess was several feet ahead of me and I knew the orangutan could very well flee before I got her attention. I choked on her name. I snapped my fingers wildly. I pointed to the trees until she finally whipped around in confusion. Realizing my strange behavior was a signal, she struggled in the same ways to alert Kinol of our visitor.

We huddled together in the dirt. The orangutan was a subadult male, beginning to transition to alpha. His cheeks were sharp, which meant his face flaps, scientifically known as flanges, were starting to protrude and develop. He was larger than most sub-adult males, and the first signs of dreadlocks were beginning to form. In a few years, he would double in physical size, reaching 200 to 250 pounds. His face would be wide and round with a deep throat pouch. His eyes would be dark as stones, yet retain the warmth of his intelligence. I’d observed alpha males and subadult males in captivity, but I’d never seen a male in transition between the two biological stages. There was so much I wanted to explain to Jess. Instead, I rushed to memorize his features.

An alpha male gazes out at the rainforest. Unlike the wild orangutan encountered by author Hayli Nicole towards the end of her trek in 2018, this one is semi-wild. Photo: Hayli Nicole.

He wasn’t thrilled that we’d seen him, so he tried to intimidate us. He grabbed a branch and hurled it below, but the leaves made it twirl gently towards us. He made a slight kiss squeak and then attempted to urinate on us. When those final attempts didn’t work, he fled. I tried to follow him as quickly and quietly as I could, but my short legs were no match for his long arms. Soon his hair disappeared behind a vine, and as quickly as he had arrived, he was gone.

Sumatra, 2019

I’d told the story of that encounter on a sailboat in Komodo to convince Sydney and our new friend to come to Sumatra with me. I had hoped returning with a smaller group would increase our chances for wildlife sightings. But it still feels like our defining moment is missing. We pause at every fungus, oversized leaf, damaged tree, and beehive for closer inspection, but the excitement isn’t the same. We follow Kinol’s mantra. We carry less so we can pay more attention to our surroundings. We are mindful of where we step. We keep our voices low. We are hyper-aware of the impact our presence has on our surroundings, yet six days hasn’t led to a single sighting of a wild orangutan.

Our final camp is along the Bohorok River; the sound of the water rushing onward towards Bukit Lawang is a reminder that this trek is coming to an end. An abandoned bamboo structure is now our three-walled shelter. Fishing poles are resting among the rocks, signaling the porters preparing for our dinner. I notice that the dense smoke from the wildfires has finally cleared. We are approaching the wet season, and the monsoons will soon provide needed relief from the flames. I pause to admire the clarity of the blue skies — a rarity when traveling during fire season and living beneath the dense canopy of an untamable landscape. I take a seat on the rocks, keeping my eyes on the trees with hopes of a final sighting.

I feel responsible for their disappointment. I feel equally responsible for the disappearance of the one thing I love the most.

A group of long-tail macaques hurls themselves through the branches across the river, stopping to munch on figs and other fruits. Though their presence is welcomed, I feel a deep pang in my heart wishing it were an orangutan instead. My trekking companions have the same pleading eyes, scanning for the slightest movements in the trees. I can feel a heaviness in the silent space between us.

Earlier in the trek, they had assured me they were thrilled, having encountered the semi-wild population of orangutans near Bukit Lawang, but I knew their hearts were set on seeing one in the wild. I feel responsible for their disappointment. I feel equally responsible for the disappearance of the one thing I love the most.

All those years ago, I’d fallen in love with Janey and her species. She’d inspired me to study anthropology and primate behavior, and to plunge into field research. She was the reason I’d first come to Sumatra. Janey gave me the rainforest, and now I see it slipping away.

In the past, I’ve been content knowing the orangutans were somewhere out there. Sleep nests were enough because it was a sign of life still thriving in this landscape, but this trek has felt unusually sparse. I think about the fires still burning somewhere in the south and the palm oil plantations that will fill the clearings once they are contained. I think about the Sumatran elephant and tiger and rhinoceros, each an endemic species teetering on the brink of extinction. And I think about the 800 individuals of Pongo tapanuliensis, the recently discovered orangutan. The potential for new discoveries in the rainforest is as profound as the current rate of biodiversity loss. The “people of the forest” now fall into both categories.

I feel my responsibility here more acutely. I want to introduce people to orangutans. I need to show them the palm oil crisis. Because one no longer exists without the other. I’ve witnessed their interconnectedness.

Sitting on the rocks along the Bohorok River, I scan the trees. What else is in there? I wonder. I fear we will never know.

Janey and Hayli Nicole at the San Diego Zoo. Photo: Hayli Nicole.

Hayli Nicole

Hayli Nicole is a perpetual traveler, collector of stories, and lover of all things mundane.

Never miss a story

Subscribe for new issue alerts.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive updates from Hidden Compass regarding new issues and other ongoing promotions such as workshop opportunities. Please refer to our Privacy Policy for more information.