Support Hidden Compass

We stand for journalism, science, history, and hope. Make a contribution to Hidden Compass and stand with us.

Burnt incense flavors the air before drifting away and dissipating in the mist. Monks in saffron robes chant tirelessly, in unison. Magenta orchids and marigold lilies adorn an altar draped in crimson fabrics.

The room is intensely sensory, a stark contrast to the drab skies outside. It’s a soggy February afternoon in 2010, and a thin fog engulfs the Vietnamese city of Hue. Hundreds of mourners have gathered to usher a departed soul into the next life. According to tradition, family members and others close to the deceased stand out in white tunics, trousers, and headbands.

Behind the flowers on the family altar is a photo of Lê Thị Hoè, the centenarian who’s passed. A handsome woman even in old age, Hoè had high cheek bones, taut lips, few wrinkles, and a formidable gaze. In the photo, she wears her tailored áo dài, a long silk tunic that displays her contours. With one arm draped over an armrest and the other resting on her lap, her seated posture exudes authority.

It is clear that Hoè had cared for the garden up until the day she died.

As with most traditional funerals, the deceased’s home hosts the ceremony. Here in Hue, traditions run deep. So do convictions.

This very house is as much a testament to that as the confidence emanating from Hoè’s portrait.

A portrait of the late Lê Thị Hoè takes pride of place inside the home she built in the early 1960s. Photo: Hiếu Trương Minh.

~~

On a drizzly September day in 1958, a proud woman in her late 40s surveys the land she’s purchased. It isn’t really land at all, but water: a muddy swamp that’s home to frogs and mosquitoes on the outskirts of Hue. She’ll have to fill the swamp in before building her new family home, and these autumn rains aren’t helping.

As Lê Thi Hoè shelters beneath her umbrella, she tries to visualize a home befitting of her family’s future. The rain can’t dampen her excitement.

Hoè’s land is on the periphery of Hue, one of Asia’s great urban masterpieces. Around Hue, networks of rivers, canals, and moats flow past gilded palaces. Hand-crafted decorative dragons and phoenixes ornament colorful temples and soaring pagodas. Along tree-flanked avenues are large, boastful European mansions built by the colonial French, who had only recently exited the country, in 1954. Perhaps most notable of all, a grandiose, walled citadel encircles a sizable portion of Hue’s inhabitants and the Imperial City, the former home of the royal family. Bao Dai, Vietnam’s last king, abdicated in 1945.

Tempering Hoè’s mood, however, is the absence of her husband.

I’m going north, he had told her, 13 years prior. His skills as a nurse were needed in those villages and hospitals, where the Viet Minh — Vietnam’s resistance movement against the French — had taken control.

Doing what she thought was best for their four children, Hoè refused to follow. She was not the first, nor the last, wife in Vietnam to lose her husband to a sense of duty.

The French had left a country in chaos, with the rival cities of Hanoi and Saigon vying for both physical and ideological dominance. Ravaged first by feudalism and then colonialism, the North sought an agrarian, communist utopia. Seduced by the material wealth generated by capitalism, the South pursued a revived system of hierarchy.

Almost as soon as the French left, Vietnam split into two factions. Hue fell into South Vietnam, but only just — placing the former royal city in the crossfire.

Around Hue, networks of rivers, canals, and moats flow past gilded palaces. Hand-crafted decorative dragons and phoenixes ornament colorful temples and soaring pagodas.

Hoè’s husband’s skills had proved essential: After he went north, the Viet Minh blocked him from returning. Once the border was erected, he and Hoè became citizens of two adversary countries, severing all contact between them.

At least she had land. Having used what little savings she had to move her remaining family from the countryside to the city and purchase this plot, she couldn’t afford to build yet. But it was hers.

~~

Five years later, Hoè shelters in the shade of a young longan tree, in silk pajamas and open sandals. She inspects her dashing house with delight. It’s brutally hot and humid, as summer days in Hue usually are, but her new abode dazzles in the bright sunlight. Nearby, artisans carve out spirited, boomerang-shaped decorative touches on the porch.

After years of cooking for strangers as a chef, servant, and restaurateur, Hoè had finally saved enough money to fill in the swamp and build her dream home.

With green fingers and an eye for style, Hoè had set her sights on building a modern garden house — a detached residence, encircled by verdant foliage, common in Hue. She had planted banana trees and a burgeoning vegetable garden — cassava roots, purple potatoes, sweet yams.

With South Vietnam less than ten years old, modernist design was emerging. Hoè engaged a young Vietnamese architect who had studied in France — a friend of her eldest son — to honor Hue’s colonial-era architectural influences while pushing stylistic boundaries. Instead of the round wood columns found in traditional Hue architecture, the architect made a square pillar from exposed aggregate concrete, a material popular for residences built during that time.

It’s single story, like other garden houses, with the living quarters detached from the rest. In the front portion, three bedrooms fan out from the atrium. Contrasting with the swirling floral patterns found on buildings built during the colonial period, the lines on this house are crisp and the shapes simple. Bold diagonal edges, a far-reaching portico, and curvy patterns speak to progressive ambitions.

Amid the swirling forces of postcolonial Hue, Lê Thị Hoè built her family’s legacy from the ground up. Photo: Hiếu Trương Minh.

Taken all together, the effect is somehow vintage, retro, and futuristic all at once. If the house were a cartoon, it would sit somewhere between the old-world indulgence of The Adventures of Tintin and the avant-garde aesthetic of The Jetsons.

But its architectural influences were just the start of the way the house would represent Vietnam’s evolving story — and the suffering to come.

~~

It’s spring in the early 1970s. Hoè sits inside her bedroom as the morning glimmer streams in through the open window shutters. From here she can see her front yard, which she’d spent the past decade transforming into a meticulously cultivated garden.

Many of Hue’s garden houses, in contrast, sit in a wreckage of rubble that chokes the vegetation. The city’s waterways remain, but many of the palaces, temples, and pagodas have been reduced to ruins. Some of the French mansions have long been deserted, while others have completely collapsed. Bombs have ripped through large sections of the citadel walls. The Imperial City is an apocalyptic shadow of its former self.

Hue fell into South Vietnam, but only just — placing the former royal city in the crossfire.

Soon after completion of Hoè’s house construction, tension between North Vietnam and South Vietnam erupted. By then the Viet Minh had morphed into the Viet Cong, an armed revolutionary organization that fought to reunite Vietnam under communism. Meanwhile, the U.S. had been steadily scaling up its support of South Vietnam. Upon taking the oath of office in 1963, Lyndon B. Johnson pledged “strength and determination” in the “battle against communism.”

By 1967, nearly half a million U.S. troops marched alongside their South Vietnamese allies. But the Viet Cong had not given up.

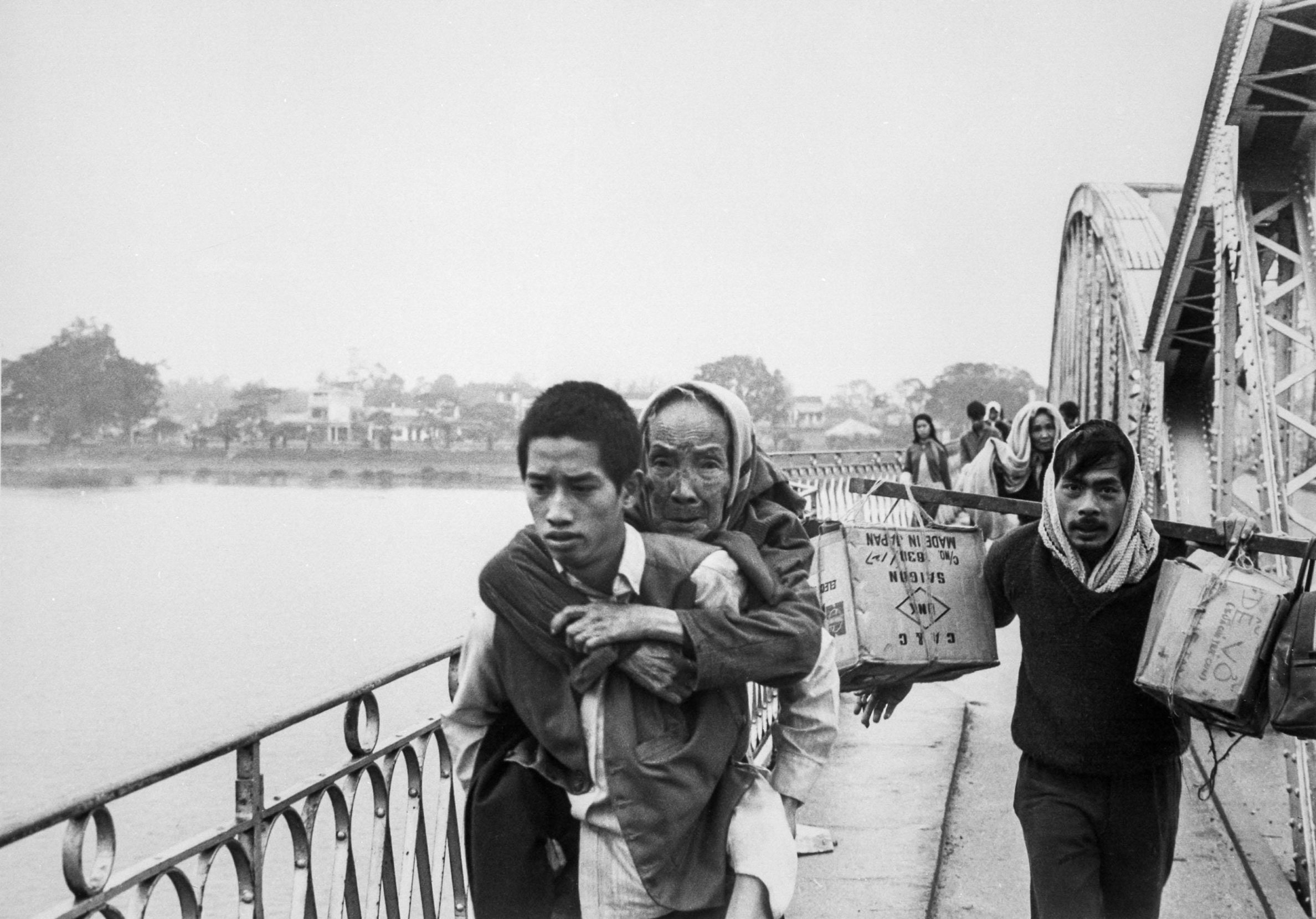

In the early hours of the Vietnamese New Year holiday of 1968, residents of Hue’s walled city faced an ominous sight: the gold-starred, red-and-blue Viet Cong flag flying atop the Citadel’s 120-foot-tall flag tower. The former imperial capital was one of five South Vietnamese cities to suffer a coordinated surprise attack by Northern forces, which had infiltrated the cities as they were preparing for holiday festivities. The Tet Offensive triggered a nearly month-long battle for Hue that killed thousands, whether by rocket fire or execution squad, and laid waste to much of the city. In the grim aftermath, survivors roamed the streets, digging for bodies, sometimes unearthing mass graves.

During the Tet Offensive of 1968, refugees of Hue flee across the Perfume River. Days later, the Viet Cong destroyed this bridge connecting the city. Photo: Everett Collection Inc/Alamy.

Remarkably, Hoè’s house remains intact, her garden healthy, and her children alive. For those blessings she thanks her ancestors and the spirits. But the sound of distant gunfire is punishing — and as unrelenting as her children’s appeals to leave the house.

Trần Thị Thiện, Hoè’s pragmatic daughter, pleads with her mother to go south to Saigon, farther from the fighting. Bolstering Thiện’s argument is that she doesn’t know the whereabouts of her husband, who fights for the South Vietnam army. Everyone has heard stories of what happens to Southern soldiers and their families.

You think that Saigon is safer? Hoè asks with raised eyebrows.

Hoè knows what will happen if she leaves Hue. The Viet Cong will abolish private landownership, just as they have in the North. They’ll take houses from hard-working families, particularly those with ties to the South Vietnam government. Hoè’s husband may still fight for the North for all she knows — she hasn’t heard from him in almost 30 years — but her sons are fighting for the South.

If she stays in Hue, she may lose her life; if she leaves Hue, she will lose her home.

~~

It’s 1975, the autumn rains have begun, and Hoè’s garden is a calamitous, unrecognizable mess. A mucky plot has replaced the cherished garden. The handsome pathway that connects the road to the house is caked in mud, traipsed in by soldiers. Rainwater sits heavy on the unkempt trees, making it hard to imagine they’ll ever bear fruit again.

The Imperial City is an apocalyptic shadow of its former self.

Thiện steps out from the cyclo — a three-wheeled vehicle common in Southeast Asia — wearing a modest maroon áo dài, which does little to mask the bump of her third child, and supporting her 3-year-old daughter on her hip. In silk pajamas and sandals, Hoè cradles Thiện’s youngest.

Now in her late 30s, Thiện has inherited her mother’s determination. As life in Hue became more dangerous and North Vietnam’s takeover appeared increasingly likely, she was finally able to persuade Hoè to desert her home and flee to Saigon, where they could look for ways to emigrate.

Then the Viet Cong overwhelmed the South Vietnamese army.

Towns along the coast fell like dominoes, with Hue among the first to go. Just over a month later, at dawn on April 30, a North Vietnamese tank crashed through the gates of South Vietnam’s presidential palace in Saigon, effectively ending the war. The United States and its allies withdrew swiftly, evacuating thousands in a panicked frenzy — with people scaling the 14-foot wall of the U.S. Embassy and fighting for space on departing helicopters.

Thiện’s brothers managed to escape. Many thousands more were left behind, including Hoè, Thiện, and the children. Their family had unraveled even further. But they had their lives, when so many did not.

With nowhere else to go, Hoè and Thiện returned to Hue to start again, back home but in a new country — one they hadn’t wanted, reunited under communist leadership. At least the war was over.

To their intense relief, Hoè and Thiện can see from the cyclo that the house is still standing. But as they walk down the path toward the house, something’s amiss.

~~

Hoè knows what will happen if she leaves Hue. The Viet Cong will abolish private landownership, just as they have in the North. They’ll take houses from hard-working families, particularly those with ties to the South Vietnam government.

The house isn’t boarded up and vacant like they’d left it. Hoè holds back, lamenting her ravaged garden. Just a few months of absence has undone years of hard work.

A stone-faced bureaucrat meets Thiện at the door and declares that this house is no longer theirs: It now belongs to the state. His northern accent is clear, harsh, and final. Thiện is shocked and speechless, but this is just what Hoè had predicted.

And where are we to live now? Hoè asks the trespasser in her house.

The official directs Thiện and Hoè to their new home, a plot buried down an alleyway and a fraction of the size. Thiện studies this cramped, crumbling, and deserted building. The whereabouts of her husband are unknown. Hoè believes he was captured during the fighting, and that Thiện shouldn’t expect to see him again.

War splits marriages, Hoè had always insisted.

~~

Throughout the rest of the 1970s, Hoè makes daily trips to government departments to try and reclaim her land, while Thiện, a trained teacher, works in an elementary school to support her children.

Meanwhile, Vietnam plunges into intense poverty. Diplomatic isolation and government mismanagement leads to famine and severe food shortages that cut already paltry rice rations. Residual wars break out with Cambodia to the south and China to the north.

Hoè’s garden languishes under shrapnel and trash dumped by soldiers.

In dealing with the new government, Hoè encounters authoritarian subjugation and bureaucracy.

My husband served the Viet Cong, Hoè cries. But your son was a traitor, they counter.

The new house is too small for my family, she argues. That’s what the state allocated, they assert.

But it’s my house, she pleads. It’s the state’s house, they correct.

After Vietnam’s reunification, the government appropriates an uncountable number of properties like Hoè’s across the central and southern provinces. Hanoi’s intention is to remove hierarchy and end inequality. But the outcome is much less noble — a corrupt transfer that punishes supporters of the former South Vietnam government.

Most families abandon what they’ve lost. Others refuse to surrender.

~~

It’s 1980 and Hue’s sharp winter hits. Hoè and Thiện wrap themselves in layers to keep back the chill while they apply a fresh coat of lemon-yellow paint to their garden house’s façade. After five long years of quarreling, squabbling, begging, and bargaining, they have reclaimed their home.

Hoè is triumphant, but the return doesn’t end the family’s torment.

Both Hoè and Thiện’s husbands have survived, though this provides the family little support or solace. Hoè’s husband is rooted in northern Vietnam and only able to visit Hue three times before he dies in a road accident. She’s grown accustomed to life without him, but the news still stings.

Thiện had received word — by a note pinned to a cigarette pack — of her husband’s imprisonment in a reeducation camp, meant to be training grounds in communist ideology and national unity. He is alive, but she can visit only as a reward for his good behavior.

And the government still doesn’t allow private land ownership, so although Hoè and Thiện are allowed to live in the house, they don’t own it. As they work to restore the structure and remake their family home, they know it can be seized at any moment.

Most families abandon what they’ve lost. Others refuse to surrender.

The government retains use of the back part of the property, arguing that a family of five doesn’t need so much space. Thiện has accepted the compromise; she has a good house in which to raise her three children, and that’s what matters most. Hoè has also accepted the deal and has set to work reinvigorating her decimated garden, rather than yearning for what she has lost.

~~

Trần Đăng Phương Thảo, Thiện’s middle child, looks at the gleaming yellow house where she spent her childhood. She’s wearing casual jeans, a T-shirt, and a baseball cap to protect against the spring sun.

The shutters sit open to entice the breeze while the swirling, baby blue floor tiles shimmer in the sunlight. The longan trees and banana leaves emanate a deep, healthy green.

Thảo takes it all in, wondering if it’s the last time she’ll lay eyes on it.

It’s 1993 and Hoè has spent more than a decade carefully invigorating her salvaged garden. Now in her 80s, Hoè finds gardening isn’t as easy as it was when she bought the land decades earlier. But that doesn’t prevent her from diligently nurturing sustenance for her family. She also tends bougainvillea and roses, which glow pink and orange.

After communism’s fall in Russia and Eastern Europe, Vietnam has begun to open to the world. Enterprise springs into life as if making up for lost time, and people across Vietnam use their fortified salaries to invest in their land. Though full land ownership is still not permitted, Vietnam now recognizes land use rights. Bigger and newer houses start to appear, and the streets begin to buzz with bikes, trucks, and the occasional car. A web of scaffolding materializes across the Imperial City, now a UNESCO World Heritage site, beginning the painstaking process of restoring the palatial buildings within.

Heavily damaged during the war, the restored Imperial City of Hue flies the red-and-yellow flag of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Photo: Leonid Serebrennikov/Alamy.

Finally, after almost 20 years, Hoè is able to officially reclaim her right to the land she purchased in 1958.

There is optimism in the air, but that can’t erase decades of hardship. Thiện’s brothers are still in the United States, and she’s decided to join them. Her husband had returned beaten and broken in 1981, six years after he was captured. Vietnam wasn’t where Thiện and her husband wanted their children to go to college, or their grandchildren to grow up.

As a new high school graduate, 18-year-old Thảo is preparing for life in California. Hoè, who is tending to her plants, refuses to go with them, and Thảo has given up asking. She understands that her grandmother will never again abandon her house.

~~

At Hoè’s funeral in 2010, Thảo greets the crowd of mourners cordially, with gentle eyes and a kind smile, before shepherding them to the altar for prayer. Thảo has adopted a leading role as the self-appointed custodian of her grandmother’s home.

Soon after Thảo left for the United States, relations normalized between the two countries, making it easier to travel between them. As it turned out, she was able to make regular visits to Hue until her grandmother’s passing.

Looking from the teal wooden shutters to the whimsical porch tiles, she considers the history that forged this house. From conversations with her mother and grandmother, Thảo knows about the pride this place had given Hoè, and also the pain. The women had given almost everything for this house. And yet that hadn’t always been enough.

Towering tufts of giant green banana leaves hug one side of the house while tall, bushy longan trees loom over the other. A grand front garden still separates the house from the road, a luxury in modern Vietnam. It is clear that Hoè had cared for the garden up until the day she died. Her strawberry-pink and marmalade-yellow roses still bloom.

The women had given almost everything for this house. And yet that hadn’t always been enough.

At the funeral, relatives speculate about the land’s worth and what should happen to it. But Thiện and Thảo, both of whom still live in California, will never sell. They maintain that it should always be where Hoè’s children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren can eat fruit from the trees and play among the flowers.

The house has become a place of worship: somewhere to honor Hoè and the legacy she created — standing proof of perseverance as well as defiance.

As the author describes the architecture, the old-world indulgence of The Adventures of Tintin meets the avant-garde aesthetic of The Jetsons in this heritage garden house in Hue. Photo: Hiếu Trương Minh.

Joshua Zukas

Joshua Zukas is a Hanoi-based writer covering travel, architecture, culture, and innovation in Vietnam and, occasionally, beyond.

Never miss a story

Subscribe for new issue alerts.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive updates from Hidden Compass regarding new issues and other ongoing promotions such as workshop opportunities. Please refer to our Privacy Policy for more information.