Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

This story, which originally appeared in our summer 2020 issue, has been republished in the winter 2025 issue of Hidden Compass to bring articles from the archives to our newest readers.

The silence echoes from every surface: the walls of vacated buildings, the streetlamps, the tunnels leading up to the mine. It plays the settlement like an instrument. Even the wind is muted, blocked by mountains framing the valley.

And then an explosion like thunder, the glacier across the fjord calving into the sea.

The northern landscapes, where the scale of things is hard to imagine, are places which inspire longing because so much is unreachable. For most of the year, parts of the fjords are inaccessible to us, filled with sea ice. For months, the sun stays far below the horizon, and the night lasts 81 days. We were not made for these territories.

In the past, people went north to those blank spaces on the maps and were confused, horrified, but faced with a subliminal beauty. They went to find what awaited in the silence, beyond our grasp.

I went north for the same reason.

Once upon a time, Pyramiden was a thriving, if remote, Soviet town. Now, it’s a nearly abandoned outpost on the edges of civilization. Photo: Dagmara Wojtanowicz.

~~

Pyramiden is a Soviet ghost town on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen, 800 miles from the North Pole. It was abandoned in 1998, when the final ship came to take its residents away. They were told to pack their most valuable belongings and wait at the harbor.

After the people left, everything stayed as it was. In the years following, many of their items disappeared — scattered by storms, visitors, and locals from neighboring settlements. But many remain.

In Pyramiden, the past bounces from wall to wall, sliding down the mine shafts, ringing from rooftops — moving in a way that makes it difficult to grasp. Here, history has a life of its own, tied to the landscape that surrounds it. To witness this town is to see how memory endures time, to see how long memory can survive and the story that grows in its place.

Eight years ago, Pyramiden received a new resident with an impossible task. Piotr Petrovich Putceruk was hired to be the keeper of this place, to preserve what was left. A ghost town governor.

~~

If the conditions are right, it takes just over two hours to reach Pyramiden from Longyearbyen, the main settlement on Spitsbergen, where I have been living and working as a guide for a few years. After going to Pyramiden several times a week for work, I’ve gotten to know the local guides and population, which is 10 people this season. Toward the end of summer, I decide to spend some days there without distraction. I want to fall into the history of the place, to walk through the deserted buildings and try to understand it through Piotr’s eyes.

On the way there, I watch innocently as the landscape shifts: The mountains get sharper, taller. The wide, blue lips of glaciers come into focus. It’s stunning but harsh. The color of the sea is the color of a dream: a blue-gray shade to get lost in.

In front of the boat, the settlement appears like a mirage, materializing from the base of the mountains. When we get closer, I see a friend waiting for me on the pier. He has a rifle strapped to his back for the polar bears that are often in the area, the hood of his jacket pulled up against the wind.

Piotr is waiting for us in the town’s bus. He’s tall, wearing dark colors and a musky cologne. He is from Ukraine, and has been living in Pyramiden since 2012.

As usual, he’s wearing a belt with a flare gun, radio, flashlight, and a set of keys for all the buildings that have been locked away from visitors. He has donned his one pair of sunglasses, which he wears even on cloudy days.

Piotr Petrovich takes on myriad responsibilities as the keeper of Pyramiden. Photo: Dagmara Wojtanowicz.

When we see each other, we hug. He hands me some colorful Russian chocolates, and I give him some Norwegian ones. I tell him thank you — Спасибо — one of the small handful of words I know in Russian. Though we can hardly say three words to each other, he is always friendly and welcoming. He agrees to bring me with him while he’s working so I can see what it’s like to maintain a memory of a place.

~~

In the late 1920s, Soviets purchased Pyramiden from Sweden. This was allowed because of the Svalbard Treaty, which gave equal access of the archipelago’s resources to signatory countries. A Soviet man went there soon after to inspect the mining prospects, and he described the silence of the place, claiming that even the waves fell onto the shore without a sound. He scouted an area at the end of Billefjord, surrounded by mountains and glaciers, where a mountain with a peak that looked like a pyramid towered high. It was the mountain where the mine would be constructed, and where the town got its name.

Of all the times I’ve seen Pyramid mountain, the top has almost always been obscured in clouds. As if even the mountain itself has become a ghost.

~~

Piotr came to Pyramiden eight years ago, after a friend at Trust Arktikugol asked him to watch over the settlement. The town was deteriorating, but the company was interested in preserving it as a monument of an unusual and surreal project of the Soviet Union. Piotr is responsible for fixing anything that breaks, driving the bus, collecting water from the lake, chasing polar bears away, and redirecting rivers of meltwater from the glaciers so the town doesn’t flood. He is always saving the place.

To witness this town is to see how memory endures time, to see how long memory can survive and the story that grows in its place.

Forces of nature try to take Pyramiden back constantly. When the rivers become heavy in the summer from glacial meltwater, they threaten to flood the heart of the settlement. Piotr makes dams out of stones to stop the buildings from being washed away. A few years ago, a polar bear broke into the hotel and stole food from the kitchen before Piotr scared him away. Windstorms have sent roofs and old mining equipment flying from their origins.

Piotr drives us from the harbor to the entrance of the settlement, where he drops off my friend so he can guide a tour for some visitors. Afterward, Piotr drives me to the hotel — a family of Arctic foxes is usually there, looking for leftovers from the kitchen. As he drives, there is no radio playing from the dash, no signal from the outside world. Because of this isolation, Piotr is essentially his own boss. He keeps a list of things he wants to accomplish for the town and hardly ever takes time off. Here, he has a clear and distinct purpose: stopping time.

But the natural world does not yield to our own nostalgia.

~~

I picture them arriving by boat for the first time, sailing up to the harbor. Ice floes drift around them. In the distance: the sharp peaks of mountains that never end. Icebergs like half-submerged castles.

In the ruins of the Second World War and the decades that followed, they’d have come to Pyramiden looking for a new life with new possibilities. For many of them, living on Spitsbergen was a way to see beyond the Iron Curtain, beyond what was known.

Some people say it was one of the craziest projects dreamt up by the Soviet Union. In the settlement of just over 1,000 people, salaries were higher than anywhere on the mainland, and since housing and food were provided, the cost of living was practically free.

The typical family arriving to the settlement came from Russia or Ukraine. I imagine a father who works in the mine, a mother who works in the hospital, their three children in primary school. They would have lived in one of the housing blocks built for families, just down the street from the culture palace — a gem of any Soviet society. Inside was a swimming pool, gymnasium, movie theater, library, dance studio, and music room. The nearby canteen was open 24 hours a day, and the elegant architecture—the high ceilings, the mosaic-studded walls, the grand staircase — made it an ideal space for social gatherings.

The abandoned pool at Pyramiden still displays a medal podium. Photo: Dagmara Wojtanowicz.

The family would have gotten fresh vegetables and fruits from the farm, which had a greenhouse, chickens, and cows and pigs — it was one of the most successful agricultural projects seen in the Arctic. The farm, combined with energy produced from the local coal mine, made Pyramiden close to self-sustainable.

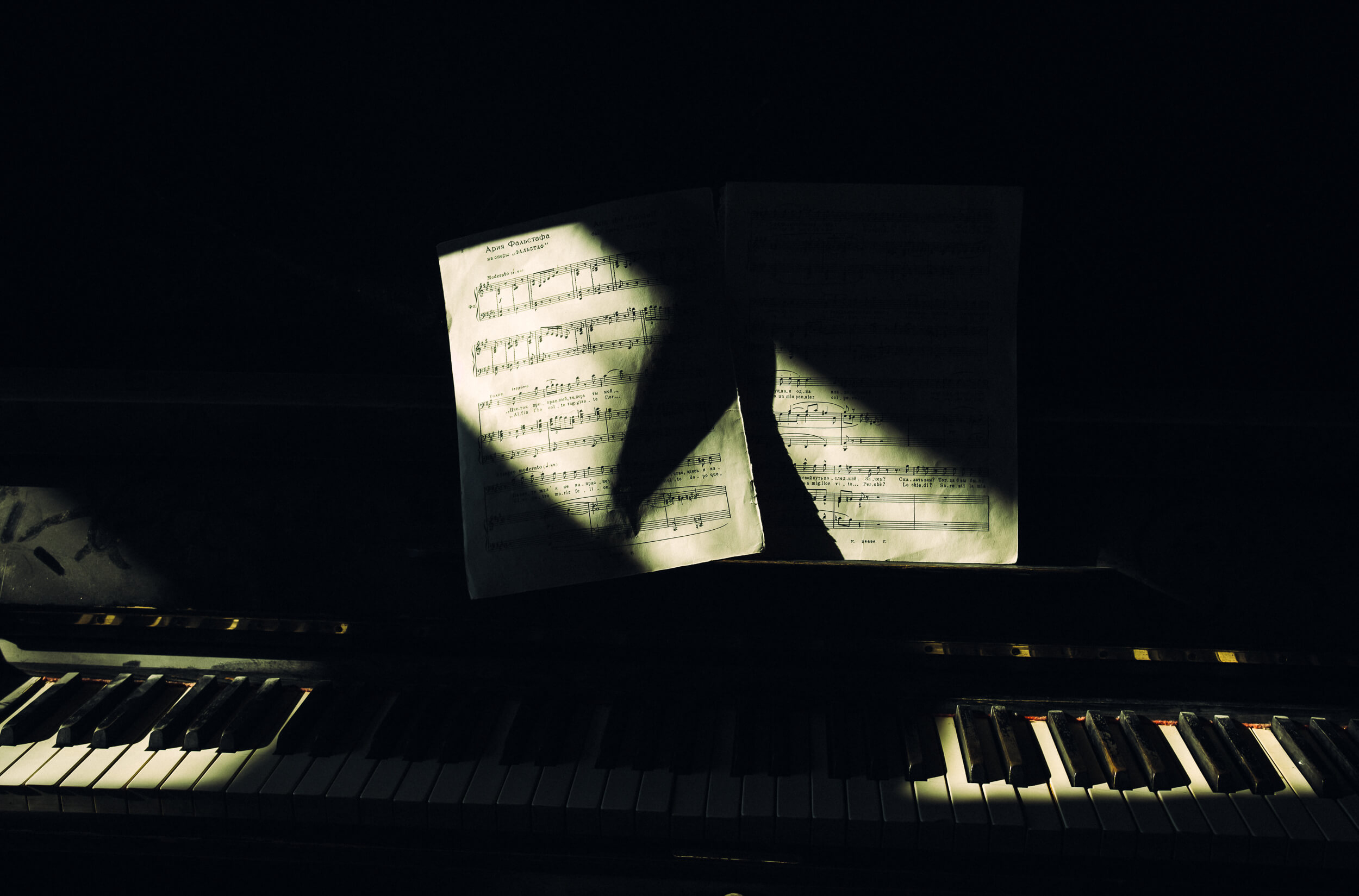

I envision the family going to the theatre to watch a seemingly endless collection of films, or concerts featuring the auditorium’s grand piano. On the evenings when the parents could sneak away, they’d go to the bar, which was open into the night.

It’s easy to picture the town in its golden age, a utopia where the known earth ended.

If it truly was a utopia, did its residents know it was only a matter of time? That even the best dreams jolt us awake, leaving us blinking in the dark, willing to trade anything to make it back to those uncharted lands?

~~

Broken glass covers the floor in most of the hallways and all of the doors are open, some missing from the frames. In the rooms: old mattresses, wooden chairs, small desks with empty boxes of cigarettes and aluminum cans. It’s hard to tell if some of the objects are from the original residents or from people who came to the town after it was abandoned. Strips of wallpaper hang from the walls, corners in the room bloom with mold. Yellowed newspapers, posters of mystery people, record sleeves. An empty aquarium.

We are in one of the old residence buildings. I walk into room after room of the four-story building, even though they all start to blur into the same picture. Even in decay, the architecture is stunning, with hand-painted wall tiles and wooden siding etched with fine details. Still, it’s hard to see it as it once was when now it’s sinking into itself. Silence fills the hallways, shadowed except for the ends, where streams of sunlight fall from the broken windows. Next door, in the storage behind the culture palace, reels belonging to a thousand films are stacked in dusty rows all the way to the ceiling.

Even the best dreams jolt us awake, leaving us blinking in the dark.

Piotr is on the side of the building, fixing one of the entrance doors. I learn from some of the guides that he had worked as an electrician and maintenance worker in Barentsburg, the other Russian settlement on Spitsbergen, in the 1980s. Before that, he lived in Poland for a while. Eventually, he was asked to move to Pyramiden and take care of the place. His wife lives with him here in Pyramiden part of the year, where she works in the hotel. After eight years of living there, Piotr knows the town better than most. His children and grandchildren still live in Ukraine.

Sometimes I wonder what makes him stay — if it’s because of higher wages or the remoteness, a nostalgia for Soviet times, a desire to care for the fragile remains of a dream? I want to ask him why he’s here, but I can’t: Piotr doesn’t speak English, and I don’t speak Russian, Polish, or Ukrainian. Even if he could understand me, I might never get the right answer — I’m not even sure if it’s the right question.

~~

A few years after the Soviet Union collapsed, funding for Pyramiden stopped. It was always an expensive project; mining for coal was not as profitable as imagined, the equipment and workers and infrastructure were expensive to maintain. In 1994, most of the women and children were sent to live elsewhere. The school in Pyramiden was closed.

In the fall of 1998, ships started taking residents away. With winter closing in, the sea ice in the fjord was getting tricky to navigate. Because of the unstable conditions, many people received short notice of when they were to be on the pier for departure. They gathered up everything they could but left many belongings behind. There’s a message in the power plant next to the harbor, written on walls and leftover documents: Прощай, Пирамида 1998.

Goodbye, Pyramiden 1998.

The last residents were gone by October.

I picture the people forced to leave, the ones who stayed until the last minute. They lean against the rails on the ship’s main deck, looking out at the place they called home, the home they’ll never get back. It’s already fading, clouds taking over the top of Pyramid mountain, a wind blowing in from the north. In that moment, maybe some of them realize they forgot something in their apartment: some photographs, a watch. But it’s too late — already the place is disappearing from view. Around them, northern fulmars coast on the ship’s slipstream, wheeling upward in high arcs and down again.

The coal mine was shut down for good. The last batch of coal was extracted but never made it far: The trolley that holds it still stands near the entrance of the settlement.

~~

I walk up to the top floor of the apartment building and look out at it all, the hallway is cold and still around me. From the window, I see the “crazy house,” a housing block where families with small children once lived. It got its name from how loud it was, especially in the polar night when all the kids played inside. After the town was abandoned, the building was taken over by kittiwakes: black and white gulls that screech constantly, nesting on the windowsills and rooftops, on the empty swing sets and playground outside the building. The crazy house stayed true to its name.

Kittiwakes nest in the long-gone windows of a building. When the people left Pyramiden, the animals took over. Photo: Dagmara Wojtanowicz.

I watch the birds from below as they orbit the building. It’s the end of summer; the young ones are almost ready to leave the nest. They practice flying, flapping in small circles from the window ledge and crying. Seasons change quickly in the Arctic — already the days are each getting shorter by around 20 minutes Fall is closing in; it’s time for the birds to go south. Always, the landscape transforms, circles back, waits for the birds to fly north again. And they always come back, year after year.

Sometimes, we humans come back, too. There was a woman who grew up in Pyramiden and returned to visit a few years ago. When she visited the apartment she lived in with her family, she stood in the center of the room and cried. She said it felt as if she was finally home.

~~

On Spitsbergen, any manmade object pre-dating 1946 is considered a permanent part of the landscape. Old trappers’ cabins, rusty cups from early Arctic expeditions, and broken wiring from mines are all protected. Human activity and the natural world merge. It’s impossible to live up here without thinking about the persistence of time. The blues and grays of the landscapes are the shades of something remembered.

Our species is nostalgic. We’re good at romanticizing the past, and we do our best to capture time: photographs, film, recordings, historical monuments.

As a keeper of a ghost town, Piotr is the protector of memory. Maybe this is why he stays. After years of working on Spitsbergen, maybe it was difficult to return to the mainland, where everything was more crowded and louder — where it was harder to seek out the silence. After eight years of running a ghost town, how do you simply decide to leave one day?

It’s hard to imagine leaving, myself. Walking through Pyramiden, I get the feeling of being lost, misplaced. It’s the sensation of traveling out of bounds. Everything is shrouded in mystery, the beauty of a pyramid mountain covered by clouds. I love the idea of Piotr’s job — safeguarding a physical memory against uncontrollable elements: nature, time. An unthinkable task, but an important one nonetheless.

Here, we can walk in a labyrinth of memory.

~~

There’s a song that Piotr sings every once in a while, usually once he’s had a few drinks in the evening. It’s a song from Soviet times called “Старинные часы,” meaning “Old Clock.” The chorus is repetitive — almost hypnotic:

“It’s impossible to turn back your life or stop time from moving, not even for a second. Even though the night is dark and the house is lonely, the old clocks are still working.”

~~

The day I leave Pyramiden, I walk down the wooden walkway that snakes over the heating pipes from town to the harbor. The boards creak beneath my weight, and behind me, kittiwakes are crying out their endless song. A flock of barnacle geese near the water lift off and fly away. Beneath some ruins from the mine, a fox skirts across the hillside. It stops and looks at me, indifferent, and then keeps moving.

As will I.

There’s a limbo to the entire town, a stagnancy not found in the rest of the landscape. The piano in the culture palace, though out of tune, still works. Sheet music from Soviet times waits on the stand. In the canteen, plants and flowers still line the windowsills and corners of the rooms. They’ve been dead for years — leaves yellow and brittle but held together. The leaves will never fall; there’s no wind to bring them down.

Sheet music rests on an abandoned piano. With so many personal belongings left behind, Pyramiden is a time capsule. Photo: Dagmara Wojtanowicz.

Pyramiden is a memory that waits to be remembered, a dream that never came true. The loneliness of this place breaks my heart as if I knew it when it really existed, but I was 20 years too late.

~~

At the harbor, I get on the boat that will take me home to Longyearbyen. It’s full of people — they’ve just taken a tour. All of a sudden: noise, conversations, civilization. In an hour, phone reception will appear again. I go to the stern and sit on top of a storage box. The whole valley is washed in a golden light from the low-lying sun, which will soon dip behind the mountains for the entire winter.

I watch Pyramiden shrink in the wake of our boat. In the silence, the past is still alive, all the quiet buildings are still somehow occupied. Already, I feel homesick for the place, somewhere I’ll never truly know except for the echo, fading once more into a dream.

Photographer Dagmara Wojtanowicz is a visual storyteller working in the intersection between fact and her personal narratives. She grew up in Poland, but lives and works in Norway.

Her photography seeks out themes that explore how humanity navigates issues in modern life, blending aspects of traditional documentary practices with a more conceptual approach.

Kelsey Camacho

Kelsey Camacho focuses on identity and landscape in the Arctic. She's also training for her first dogsledding race.