Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

Peach ice cream dripped down the waffle cone in my hand. Ceiling fans whirled above. My rocking chair creaked on the wide plank floor. Throwback farming implements and antiques filled every corner of my surroundings, an old peach packinghouse by the name of Dickey Farms.

While immersed in this nostalgic ecstasy, I spotted C.F. Hays & Son General Store across the street.

The old brick facade with its Nehi, Orange Crush, and NuGrape Soda signs called out to me with just enough rust and patina to indicate they were probably original. Wooden benches in front of the store windows offered shaded respite from the Central Georgia heat, already well into the 90s on this summer day, the same as they would have in the store’s early 20th century beginnings.

There isn’t much else in Musella, Georgia — not even a stoplight — but I am far from the first photographer to find reason to pause in my journey here.

~~

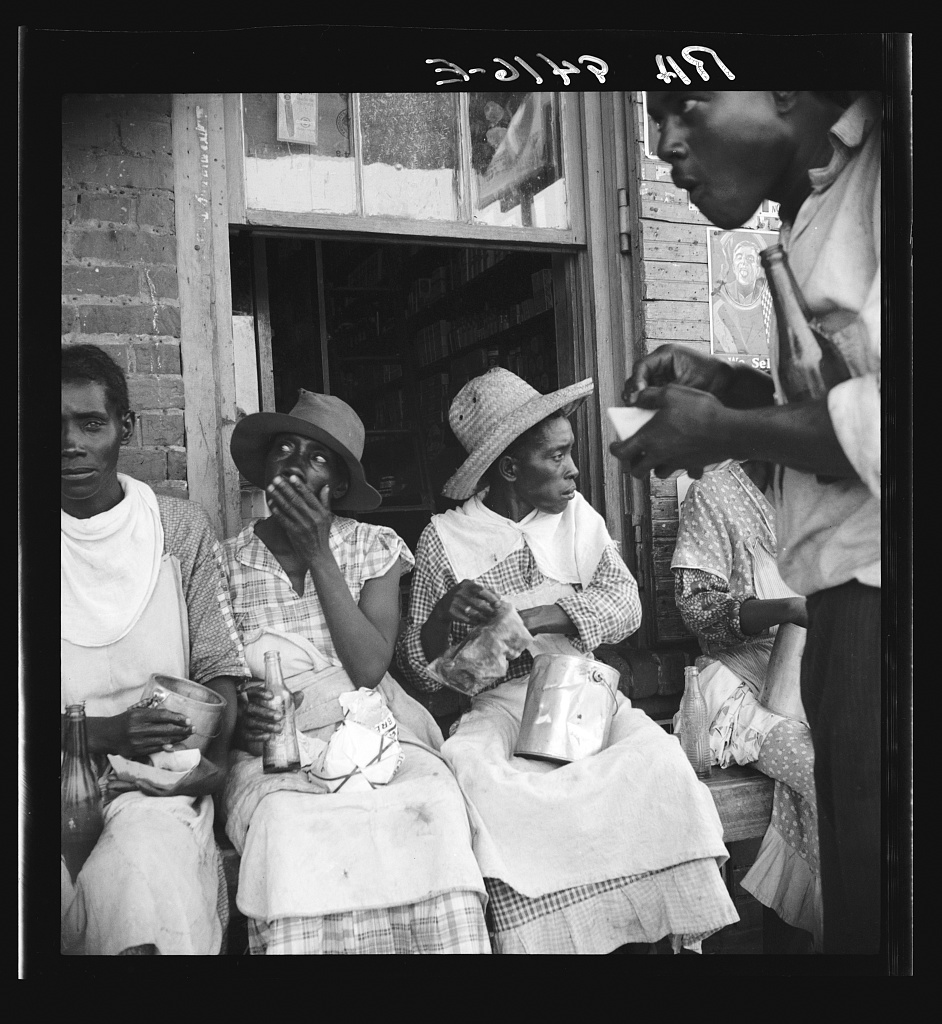

Black workers, resting on a bench, balance lunch pails on their laps. A woman has her hand to her mouth as if she is surprised by an unseen speaker. The windows of the store are open — Gulf Oil cans stacked in a pyramid just inside while an advertisement proclaiming “Navy Sweet Snuff: None Better” adorns the brick walls outside.

It is July 1936, the moment and setting immortalized in a series of black-and-white pictures. The photographer’s caption for one of those images described the scene: “Lunchtime for these Georgia peach pickers. They earn seventy-five cents a day in the orchards.”

In the right hands … that camera becomes an extension of the artist, and the resulting images do more than capture a moment in time. They hold a story forever.

~~

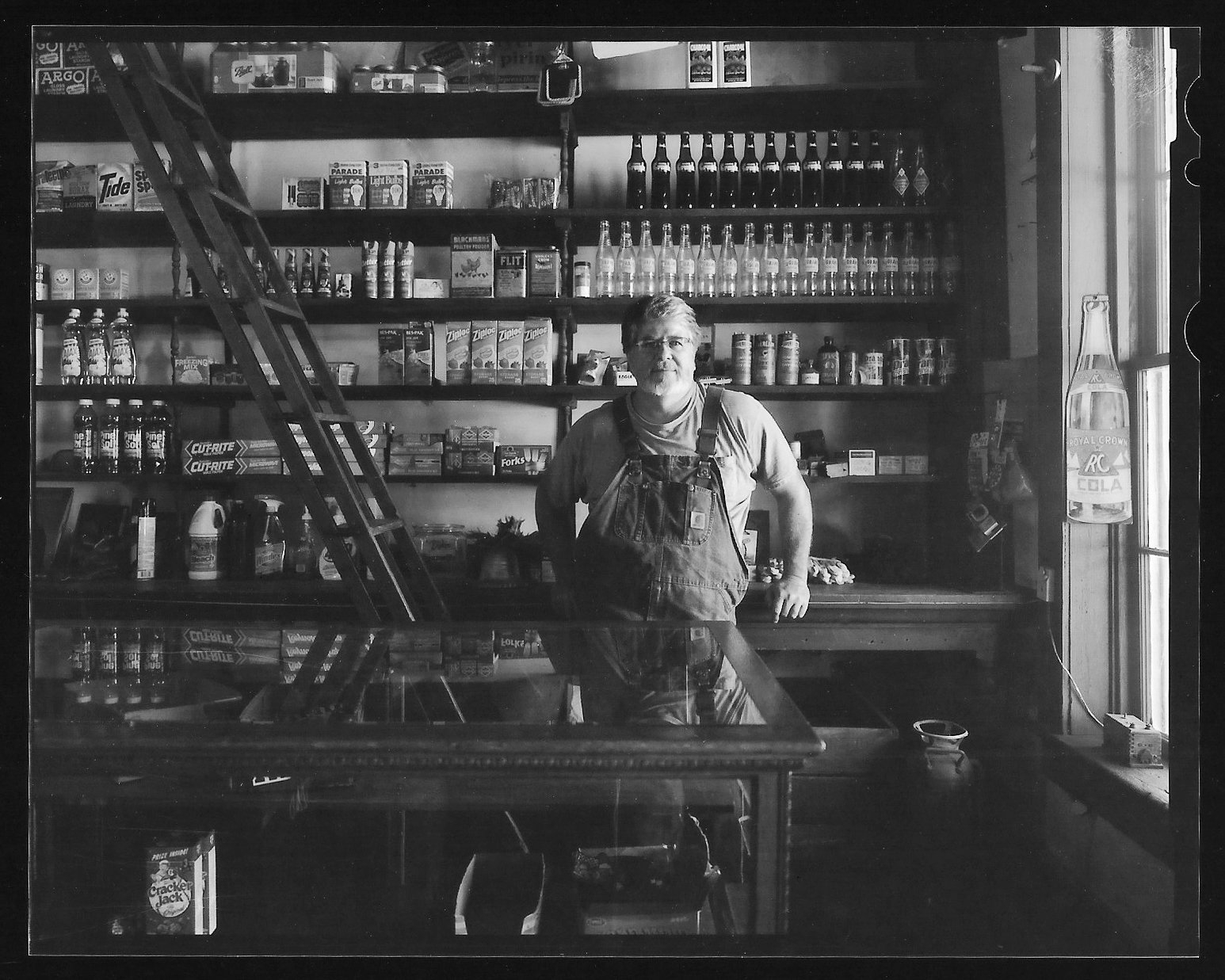

Inside C.F. Hays & Son General Store, light streamed through the large front windows highlighting the old-fashioned cash register, tall shelves, and wooden ladders used to reach the goods stacked to the ceiling. Brands of flour, razors, sewing supplies, soda bottles, oil cans, and fan belts I had only known through history intermingled with more familiar staples: Tide, Pine Sol, Ziploc, Ajax.

Taped under a glass countertop was a yellowed copy of The Macon News, its headline proclaiming, “The King Is Dead” — the day after Elvis Presley died in 1977. But something next to the newspaper caught my attention, making me do a double take.

A series of photocopies showed six photographs of peach pickers eating lunch, the moment of rest evident on their faces. I knew the style well: the solemness; the overall weariness; the loose-fitting, well-worn clothes.

At this small store, in this wide-spot-in-the-road town, was I really seeing these famous, historic photographs?

A man behind the counter, who appeared to be in his early 50s, saw me looking at the photocopies and came over to say hello. He introduced himself as store owner Cary Hays.

“These are great photos,” I said.

“Yeah, they were made by a famous photographer back in the 1930s but, you know, now I can’t remember the name,” Hays said.

“Dorothea Lange?” I asked.

“Yep, that’s it! You’re the first person to walk in here and know the photographer who made those images.”

As I examined the photocopies of the images, I could almost feel the heat of the day in the texture of the wood and brick on the walls — the same walls that now surrounded me. Moments before, I had passed by the same benches on which the peach pickers rested.

A historic photograph immortalizes a 1936 lunch break in Musella, Georgia. Photo: Dorothea Lange/Library of Congress.

~~

In 1933, a crowd of harried men lined up outside a soup kitchen in San Francisco. Watching the men drifting about was a woman at the window of one of the nearby buildings. She grabbed her camera and took to the street.

The scene compelled Dorothea Lange, a successful portrait photographer for wealthy urbanites, out of her comfortable studio and into the midst of the suffering that surrounded her.

One of her pictures from that day, “White Angel Breadline,” shows a weary man holding an empty cup, his face obscured by the low brim of his dirty hat, and a sea of men’s backs behind him. The moment she captured reflected the struggles of many Americans during the Great Depression. It was her first documentary photograph, and it changed the trajectory of her career.

In 1935, the federal government sought photographers to help document and educate the public on the conditions some workers faced. The Department of Agriculture established a photographic unit within its Resettlement Agency, later renamed the Farm Security Administration, and Roy E. Stryker was put in charge. Lange was one of the first photographers he hired.

A tiny woman with a limp left from a childhood bout of polio, she carried a heavy 4×5 Graflex camera. “Yet she somehow could blend into a crowd,” as her granddaughter, Dyanna Taylor, later recalled.

Dorothea Lange in 1936 in California. Photo: Dorothea Lange/Library of Congress.

As Lange set out from the city and onto country roads in search of subjects to photograph, she presented what the camera saw: poor and displaced people, raw and unfiltered. There were few smiles: mostly blank stares or pleading eyes on the faces of those not knowing where their next meal might come from. The vivid emotion that came through often hit viewers square in the face.

Decades later, those images ignited my passion as a documentary photographer.

I learned early on anyone could hold a camera and take a picture. In the right hands, though, that camera becomes an extension of the artist, and the resulting images do more than capture a moment in time. They hold a story forever. I wanted my hands to be the right hands.

~~

In Musella, in the presence of Dorothea Lange’s images of those peach pickers, a project began to take shape. I wanted to visit the Georgia communities Lange had, from Hartwell to Homerville — to come face to face with the people who live there today and find out what they might have to say. In the process, I expected to bear witness to the changes that have transpired over the past 8 1/2 decades.

“I can’t understand people who just close the doors on history.”

I would document their stories through the lens of the same large format, black-and-white, hand-printed silver gelatin film photography that Lange had mastered.

Naturally, my first session was with Cary Hays at the C.F. Hays & Son General Store.

~~

The store’s central location in Musella made it a popular stop for locals. Hays seemed to know everyone who stopped by the day I returned for the photo shoot. They were all quite interested in my camera.

“You filming a movie?” one person asked.

“You shooting a commercial?” asked another.

I’d heard the questions before. I use a Calumet 4×5 large format film camera that requires a tripod and dark focusing cloth. People are always curious about it, wherever I set it up.

Lange’s camera had a mirror, or reflex, that allowed her to hold the camera in her hand and look down from the top of the camera through the lens. Without a reflex viewing method, mine works a little differently. It is imposing and creates a spectacle as I disappear under the dark cloth to focus.

I bought it in 1980 to get into the Large Format Photography class at Southern Illinois University. With a lens included, it cost around $400. That’s the same camera I use today. It is a workhorse, and I have used it everywhere from the Ancestral Puebloan cliff dwellings in Colorado to the San Antonio Missions in Texas, from the cornfields of Illinois to the Blue Ridge Mountains of Georgia.

No matter where I take it, this old-fashioned still camera is an enigma in a world of digital cameras and smartphones.

An inverted image is exposed directly onto a sheet of film. The experience is almost intimate as I look through the ground glass unseen by my subject. For the few moments I am hidden by the dark cloth, I feel removed from the scene — and able to see it with more clarity.

~~

As Hays stood in front of the lens, he wore overalls and leaned back on the shelves behind a glass display case.

Cary Hays keeps the C.F. Hays & Son General Store running in Musella, Georgia, carrying on a family tradition that started in 1900. Photo: Eric Dusenbery.

“People just fall in love with the store,” he said. “It started failing back in the 1990s — it just stopped supporting itself. Local people didn’t work around here anymore. It’s like every small town.

“There are schoolteachers, truck drivers, but not so many farmers. I work at the post office. Being a mail carrier is my regular job. But, it pays to keep the store here open.”

As we continued to chat, I asked Hays more about what the store was like in its heyday. Practicing what I call slow cooker journalism is a necessity when using the large format camera — and also allows me to interact with subjects, to give a story the time to develop. Deep conversations about place and history can simmer over time.

“When I got out of high school in 1986, I started working here,” Hays said. “It was still a grocery store then. But it was an older generation that came in, and they were dying out. Other folks wanted variety. I don’t know if our shelves will hold all the different varieties of ketchup that they make anymore. I wouldn’t even know what to put in here that people would buy. They’d want no sugar-added sorts of things.”

Hays paused and looked around the store almost as if he was seeing it through new eyes.

“I couldn’t bear to close the store. I grew up in this store. I can’t understand people who just close the doors on history and sell out. I get emotionally attached. I wanted to keep this going.”

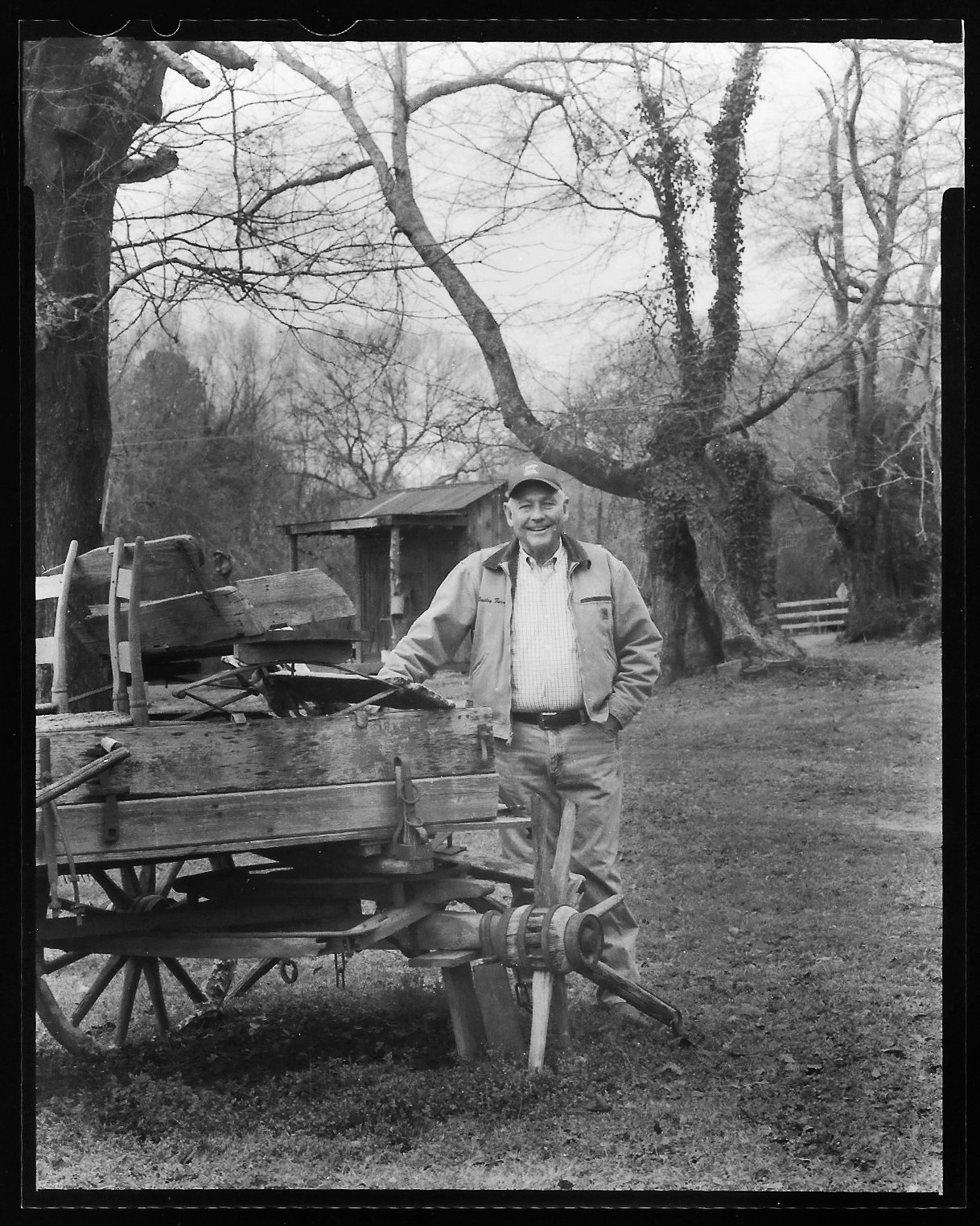

Danny Bentley poses on his land near Thomaston, Georgia, where his great-great-great grandfather first moved in 1824. The property is scattered with old farm equipment — sickle mowers, this wagon, missing one wheel, that is believed to have been built around 1880, and an outhouse that might be just as old. Photo: Eric Dusenbery.

~~

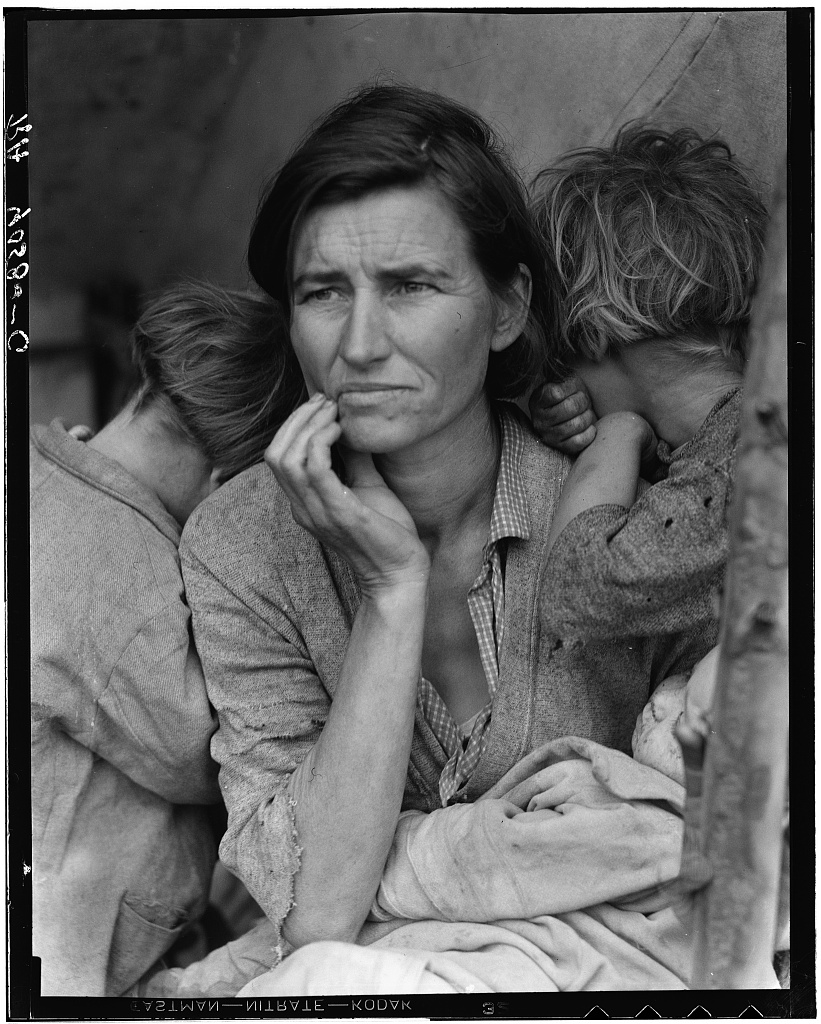

One drizzly March day in 1936, Lange came upon a sign for a pea pickers’ camp along the roadside in Nipomo, California. Though at first she drove past, something compelled her to make a U-turn on the “wet and gleaming” highway and follow a muddy road to what turned out to be a sprawling campsite for thousands of farm workers.

She took out her camera and began photographing a woman and her children in a small tent. Making five photos, she got closer with each one — “as if drawn by a magnet,” Lange later recounted.

Lange recalled that the woman had said she and her children were living off peas and other vegetables that had frozen in the field.

One of the resulting photographs shows the woman with her hand to her lined face. Her children huddled behind. After appearing in a San Francisco newspaper, “Migrant Mother” became Lange’s most iconic photograph.

Forty-two years after her face became an unwitting symbol of the Great Depression, Florence Owens Thompson wrote a letter to the editor of her local newspaper and revealed herself as the woman in the photograph. She disputed details of Lange’s account, namely that she and her family were archetypical Dust Bowl refugees. In 1936, Thompson, whose parents were Cherokee, had been a 32-year-old widow working multiple jobs to support her seven children. When their sedan broke down along U.S. Highway 101, she and her younger children had taken refuge at the camp while two older sons went into town to get their car fixed.

Thompson said Lange never asked her any questions. Recounting the encounter to a magazine in 1960, Lange didn’t remember how she explained her presence to the woman. She hadn’t taken any of her usual notes.

Florence Owens Thompson became an unnamed icon, “Migrant Mother,” after the publication of Dorothea Lange’s photograph of her at a pea pickers’ camp in California. Photo: Dorothea Lange/Library of Congress.

~~

Over the next couple of years, Lange moved on to the dust and dirt of rural roads in the South and West. She met peach pickers, cotton and tobacco sharecroppers, tenant families, and turpentine workers.

A photograph shows her in California — wearing wide-legged pants, her short hair tucked into a beret — holding her massive 4×5 Graflex camera in her lap, her thumb resting on the shutter button. She sits atop a Ford Model 40 for better vantage, her high-top sneakers dangling.

I pack my own 4×5 camera, tripod, and everything else in my Chevy Silverado pickup truck. I stow equipment and gear on a shelf I built in the crew cab.

In the field, using the 4×5 camera requires patience and self-discipline. There are no mirrors, computers, or electronics. But it can be the ultimate tool for capturing people in their environments. From the first time I used the 4×5 to shoot an assignment in that college class, I knew I would always appreciate the heft of the camera and the precision it required to make one image.

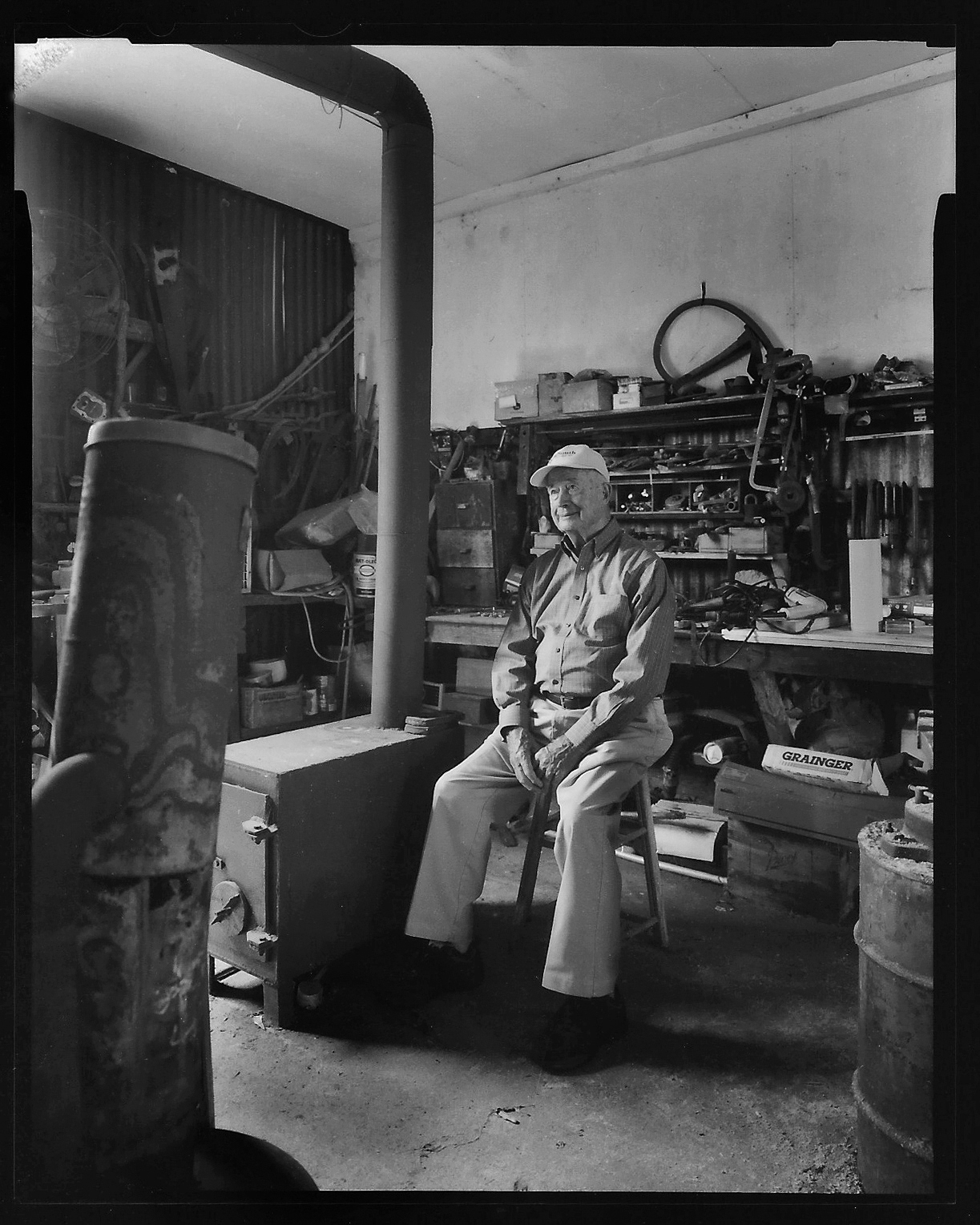

Surrounded by an array of machinery, metal barrels, and tools, Charlie Harris settles in next to the wood-burning stove in his workshop — or “piddlin’ space,” as he calls it — at his dairy farm near Musella, Georgia. “I was born and reared on the farm — the old homestead place goes back to 1885 and it’s still in the family,” Harris said, although that is not where he currently lives. “I’ve got too much of Crawford County under my fingernails to think of living anywhere else.” Photo: Eric Dusenbery.

~~

In 1937, a turpentine worker walked along a dirt road that meandered through a stand of pine trees near Waycross, Georgia, deep in South Georgia. His overalls hung loosely from his thin frame as he held a heavy turpentine bucket in one hand and a dipper in the other.

In Lange’s picture of him, he doesn’t smile, his face embodies that same time-worn look of so many of her Depression subjects.

Dorothea Lange met and photographed this “turpentine dipper” near Waycross, Georgia, in the summer of 1937. Photo: Dorothea Lange/Library of Congress.

During Lange’s trek here, she encountered the same wide, flat land and open fields I do today. Where I live, about 70 miles northwest of Waycross, in the rural community of Tifton, more tractors can be seen on the road than cars most days. Some of these machines are behemoths with plows, discs, bush hogs, and fertilizer tanks taking up two lanes, which is usually the whole road. They operate in fields of peanuts, cotton, corn, and watermelon, and I often find myself behind them on the road.

Jennifer Miller lives in Uvalda and works in nearby Hazlehurst. A county extension agent, she spends her days meeting with farmers to help with their agricultural needs, including problems with disease or insects, best practices, and any other topics they face. She also works on her own family’s farm where she grew up. “Back when I was younger, there were a lot of women, like my mom, who were their husband’s right-hand,” she said. “My mom was on the tractor but she was still caring for me. I was never told that farming was just for boys. It never crossed my mind.” Photo: Eric Dusenbery.

It was against this backdrop that I noticed an art gallery in town housed in a historic bungalow. It was nicely painted with an inviting curb appeal.

Walking in the door, I found colorful art on the white walls. Ceramic pieces, placed on pedestals throughout the airy room, included everything from a simple coffee cup to colorful horses and fish. The quality of art in such a small town was a pleasant surprise.

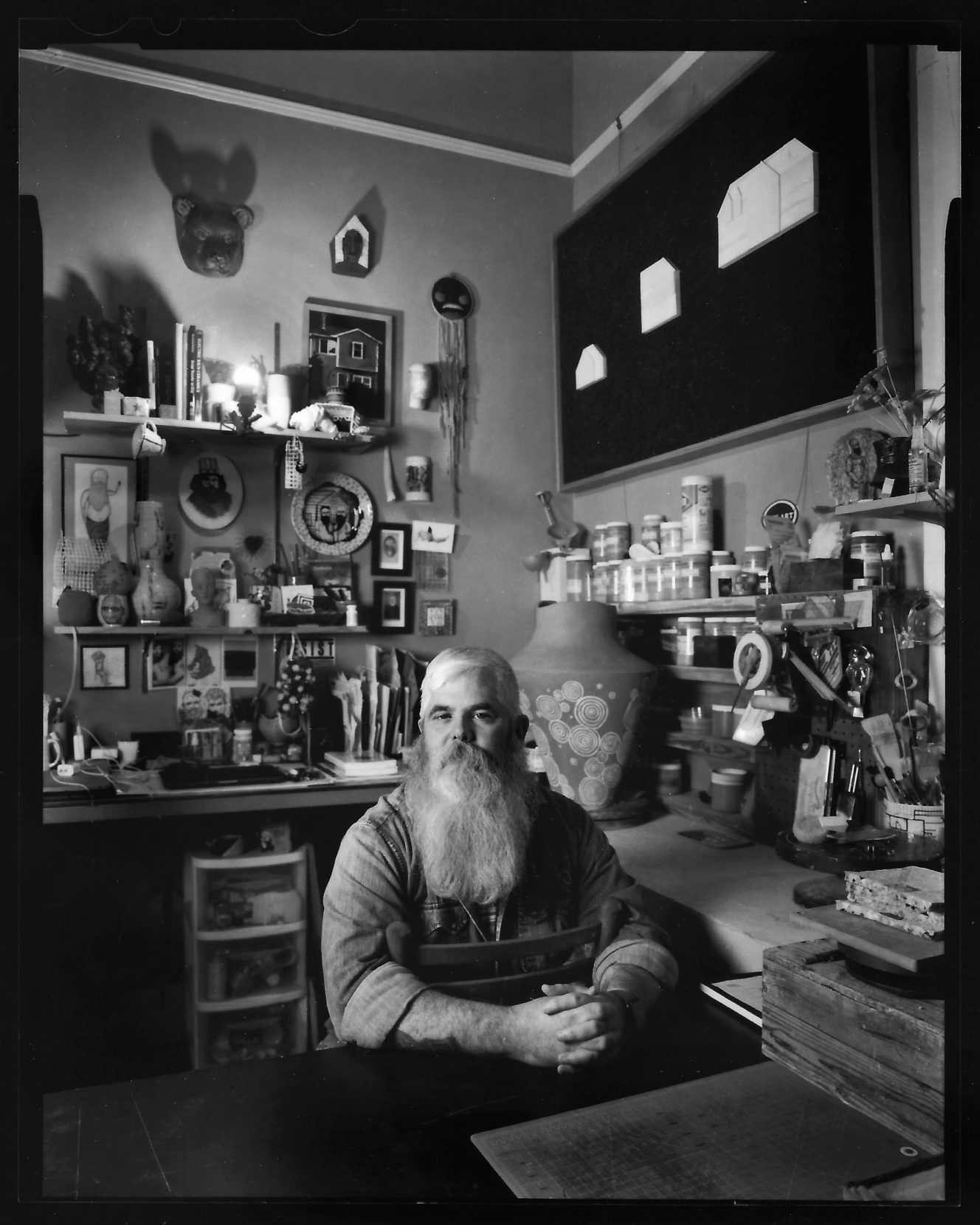

“The community has been very receptive to what we’re doing here,” said Mark Errol, gallery co-owner and artist, who explained how the gallery’s name, Plough, was pronounced “plow” — but spelled differently to stand out. He called it a conversation starter.

I mentioned my intrigue about the paradox of such a gallery in this agricultural area.

“In an agrarian society, you harvest things from the earth to feed and nourish the community,” said Errol as he relaxed in his back studio, his long beard covering the top of his denim shirt, and his sleeves rolled up to expose powerful forearms. “We do the same thing here.”

His piercing eyes seemed to represent both the artist and the intellectual. He had found a community that was hungry to build a personal relationship to art, through functional objects that can be touched.

The power of a tactile experience is timeless.

Mark Errol sits in his backroom pottery studio — the seed that germinated into his Tifton art gallery, Plough, in 2014. Photo: Eric Dusenbery.

~~

In the darkroom, I turn off the overhead lights and wait until my eyes adjust. The developer, stop bath, and fixer have already been poured into their respective trays.

The red glow from a darkroom safelight provides just enough illumination without affecting the light-sensitive paper. I put a negative into my enlarger, set the aperture, and examine a test print, determining the correct amount of time for the image — eight seconds. After exposure, I remove an eight-by-ten sheet of paper from the easel and submerge it in the developer. Gently agitating the tray, I tip the corner of the tray up and down, making sure that fresh developer reaches all parts of the paper.

I wait patiently to see my pictures emerge. Each time, it feels magical when the chemical reactions cause the latent image to appear on the photo paper, seemingly out of thin air — the ghost of this region’s forebears reaching to me through the chemicals as I get my hands wet.

Lee Morehead surveys the operations at his pecan company in Irwinville. “Back in the early 1980s, farming wasn’t real good,” Morehead said. “We went through several bad years and we just needed some extra income. So, we started buying and selling pecans. Daddy had bought and sold pecans when he was younger, as did his daddy before him. So Daddy rented a little tin building that used to be part of an old gas station, and we started using that. We just kept getting bigger and bigger each year — more and more people were coming in.” Photo: Eric Dusenbery.

~~

Chickens met me as I pulled up at Andrea Story’s place. Near the coop, the setup for a birthday party later in the day seemed incongruous with the historic former hunting lodge I was there to see. Story came out the front door barefoot and wearing a light-blue dress.

While Lange was able to photograph subjects as she encountered them in daily life, I knew better than to wander onto someone’s farm unannounced in the 21st century. In years past, I might have driven up to a farm that I thought had photo possibilities. Barking dogs met me on many occasions, and I felt a bit of trepidation as I strode up to front porches to explain a project to whoever might answer the door.

In An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion, Lange referred to her photographic subjects as “living participants who can speak.” She took field notes about her encounters, at times only managing to jot down basic information.

She presented what the camera saw: poor and displaced people, raw and unfiltered.

For my subjects, I made appointments, relying on referrals to find willing participants, and I documented each lengthy conversation with digital recordings.

Inside the lodge, gleaming wood floors and trim had been painstakingly restored. At one time, every closet had deadbolts and gun racks, and deer heads were mounted everywhere. Story and her husband wanted to take it back to the original farmhouse aesthetic.

After a tour of the lodge, we settled in the kitchen. I always ask the same first question: “Were you born and raised around here?”

“You have no idea how from ‘around here’ I am,” she said with a wistful smile. “I grew up on a farm about 10 minutes from here. Generations and generations of family farmers.”

Andrea Story takes a seat in the historic former hunting lodge she and her husband have restored and made into a family home. After they purchased the property, they were surprised to learn that the structure originally belonged to her husband’s grandfather. Photo: Eric Dusenbery.

Studying anthropology at college in Atlanta helped Story understand the way the culture of modern farming is developing. She doesn’t like modern corporations — farming the big agribusiness sort of way.

“I think young farmers are trying to capture something like what my grandparents and great-grandparents had — because we have to,” she said. “We don’t have the years of plenty that the boomers had behind us. There’s been a real reemergence of Southern skills. A lot of women my age are trying to learn to sew. My mom’s generation didn’t do that.”

The satisfaction of doing something by hand isn’t the only thing that connects us through the decades. Though the means have changed, fulfilling a need, whether personal or civic, remains a universal desire.

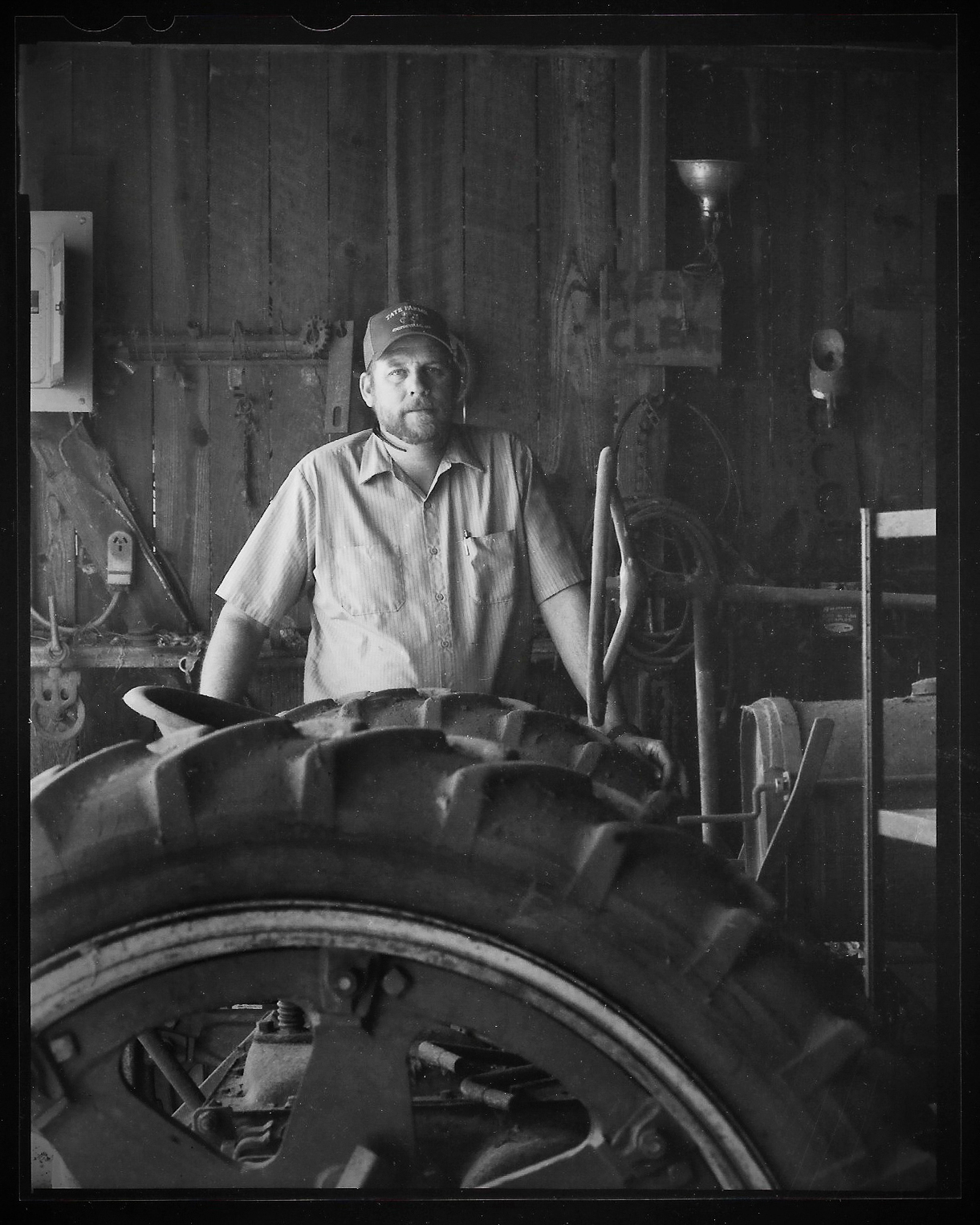

Jamie Tate is a fourth-generation farmer who took the land over from his father. He has two sons, ages 10 and 13, who he would like to see carry on the farming tradition. But the enterprise continues to evolve. “We used to have to watch television to check commodity prices,” Tate said. “Now, I can check prices on my phone any time of day. Our smartphones give us everything at our fingertips.” While he still drives a tractor for 10- to 14-hour days, the time sitting in the seat can be used for checking emails, ordering parts on the internet, checking weather forecasts, and keeping up with those commodity prices. Photo: Eric Dusenbery.

~~

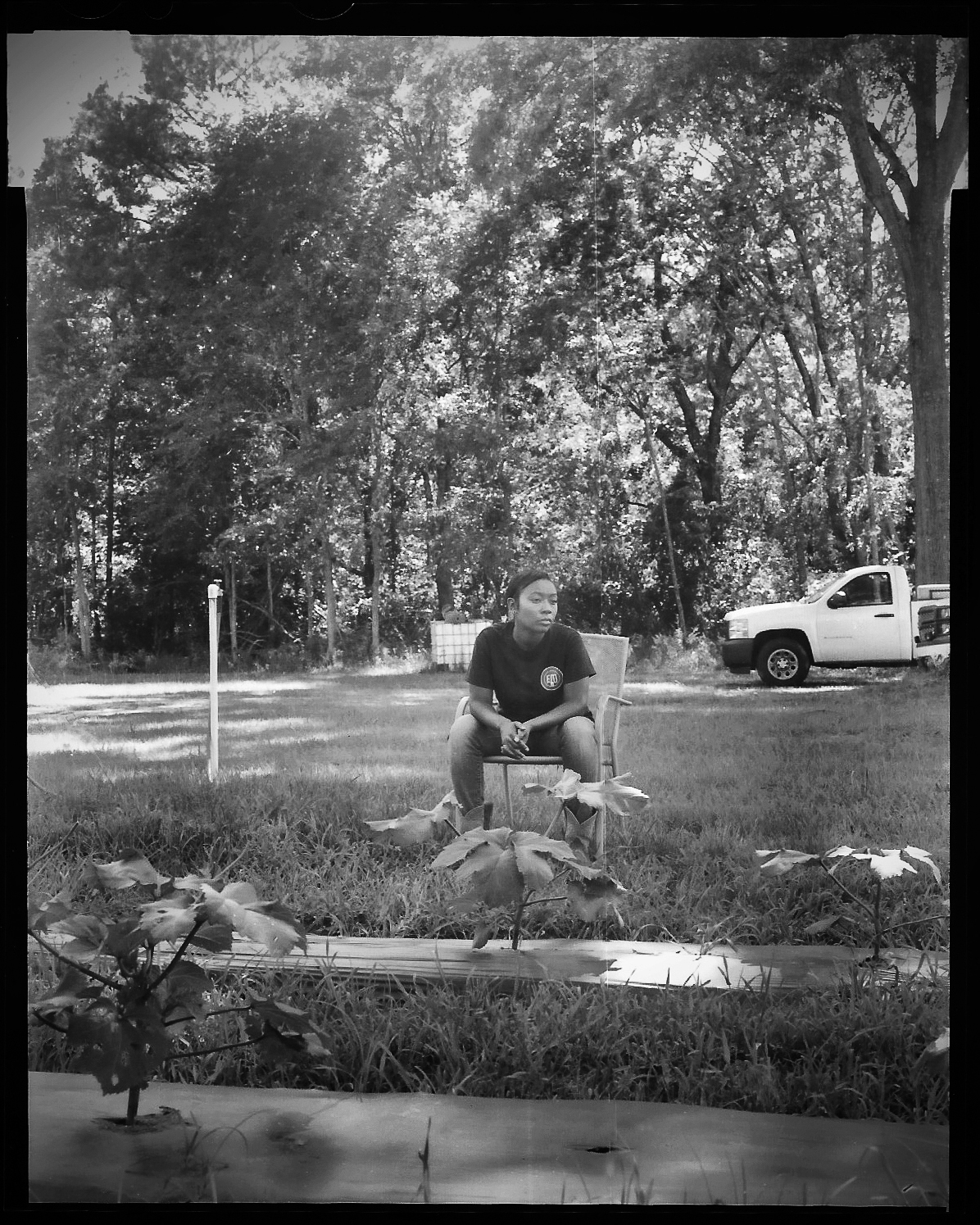

On a day when the temperature hovered around 95 degrees, under the dark focusing cloth I examined a composition of Kaneisha Miller on the ground glass. I clicked off an exposure, slid the dark slide back into the film holder, turned it over, and made another exposure on a sheet of film.

Miller seemed at ease sitting in front of the camera, wearing a black T-shirt with jeans and work boots.

Finished, we headed for a shaded picnic table. Miller is a young farmer and entrepreneur working a small piece of land that has been in her family for generations. In front of us were rows of black plastic mulch underneath broccoli, squash, tomatoes, peppers, and okra. A rear-tine tiller stood in the middle of her field as though she had just walked away from it a few minutes earlier.

As we began to talk, Miller was a little shy. As she warmed to the topic, though, her love of the land around us was evident.

I wait patiently to see my pictures emerge … seemingly out of thin air — the ghost of this region’s forebears reaching to me through the chemicals as I get my hands wet.

Miller’s grandfather, Pig Miller — she doesn’t know how he got the name — farmed this land.

“They had to do everything by hand, like putting up five miles of fence posts next to the road,” she said. “My dad said that 40 years ago they’d sell watermelons and produce right out by the road.”

What he didn’t sell, he would give away to the community. Many times, people would come to his house to eat when there wasn’t enough food at home.

The land for Miller’s farm was from her grandmother’s estate, but it had been sold. Her father bought it back in 2017 and gave some of it to her. She started growing her own produce and soon realized she enjoyed farming.

So Miller set up a table by a big pecan tree on the property and posted on Facebook that she would be out there selling produce every Saturday.

In the same spirit of her grandfather feeding his neighbors, Miller said, “The community supported me.”

Kaneisha Miller named her business, EM Farms, for her grandmother, Emma “Maude” Miller. “I used to catch the school bus at my grandmother’s house in the morning. She’d make sure I had a biscuit and egg sandwich, and I’d have one as I was running out the door. She put it in a piece of wax paper that we toted on the bus,” Miller recalled. Photo: Eric Dusenbery.

~~

During my first session at the general store in Musella, a group of onlookers had gathered to watch me set up the camera. When I was finished, I let two teenagers take a look through my camera. I told them what to expect when looking at the ground glass.

“Everything will be upside down and reversed,” I explained. “Light is passing through the lens and directly onto a sheet of four-by-five-inch film inside the camera. It’s not like your smartphone.”

One young man in jeans and a T-shirt, who looked to be about high school age, couldn’t contain his curiosity about this old-fashioned contraption. He leaned down toward the back of the camera to view the scene in front. I carefully placed the dark focusing cloth over his head.

“Wow. It’s like he’s standing on his head,” he said, wonder in his voice.

Two older men, regulars who often sat on the front benches at the General Store, also watched the spectacle. One of them, who held the attention of the teenagers by exhaling his cigarette smoke through his nose, chuckled softly.

“You don’t see cameras like that much,” he said.

Nor, a store like this, I thought to myself.

But that doesn’t mean the past is gone. Following in the footsteps of Dorothea Lange hadn’t been a wistful exercise in nostalgia, just as my preference for a large format camera isn’t about rejecting technology. Rooting myself in both helps me better understand the present, poising me to see connections as they emerge out of the shadows.

All it takes is slowing down long enough to notice.

Eric Dusenbery

Eric Dusenbery is a photographer and storyteller who doesn’t mind getting lost to find ordinary subjects that are otherwise overlooked.