Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

The smooth lines of Warszawa Centralna, Warsaw’s central railway station, ejected passengers into the concrete courtyard of a large, modern mall — cold architecture on an even colder night.

Across the boulevard from the station, I spied what I was looking for: a sprawling rectangular complex of art-deco buildings surrounding a central tower that rose 42 stories above the Polish capital city. It looked like a giant wedding cake. Built in the 1950s as a gift from Joseph Stalin, the 3,288-room Palace of Culture and Science served as a humanist temple to the People’s achievements in the arts and sciences. But I wasn’t here for the palace itself.

CINEMA. THEATER. MUSEUM. RESTAURANT. Serif. Seductive. On a cold winter day nearly seven decades after it was built, the palace continued to fulfill its original function — right down to those neon letters.

The heart of Warsaw, Poland — featuring the 42-story, 3,288-room, neon-lettered Palace of Culture and Science (right, with illuminated tower) — beats brightly at night. Photo: Manfred Gottschalk / Alamy.

~~

For hundreds of years, Polish history has been defined by the dueling aggressions of neighbors Germany and Russia — great powers to the east and west. As I dragged my rolling suitcase down Warsaw’s central boulevard, Jerozolimskie Avenue, in the biting cold, I recognized both influences. Gleaming BMWs and clanging trams; towering steel-and-glass skyscrapers and squat symmetrical blocks of sandstone with concrete columns and windows thinly lined in fading gold-colored trim. Art and commerce, style and practicality, all intermingled.

Tying these architectural and cultural influences together, a pleasant electric glow hung in the air, soft like analog film. Down the street, a 10-story mid-rise sat dark except for a bright red arrow chased by a giant looping spiral. The curved neon line began at the top floor on the south side and swirled its way across and down seven stories to an arrow on the third floor of the north side. A few blocks away, a drugstore was rimmed in red chevrons and squiggles. A blinking neon orb lit another rooftop.

Neon tubes are a sort of time capsule. Their luminance is created by trapping one of a number of rarefied gases — mostly noble ones — in a glass tube with electrodes on either end. Add a little electricity — or for large displays a lot of electricity, up to 15,000 volts — and the gas inside ionizes into bright plasma. Each gas produces its own entrancing color: Neon gas glows red, krypton glows yellow, argon blue, and so on. Once lit, they burn brightly as long as the gas in the tube is not depleted. When properly sealed in glass tubes, neon light can glow for up to a decade without dissipating.

In more ways than one, those tubes keep the past alive.

~~

It’s 1926, and the discovery of neon gas by British scientists William Ramsay and Morris W. Travers, 28 years ago, has revolutionized the advertising industry. At the Paris Motor Show in 1910, French inventor Georges Claude exhibited neon displays, and those designs quickly began illuminating city streets. By now, the trend has rolled through London, Hamburg, and Los Angeles, and has arrived in Warsaw.

From cable cars and buses, buggies and motor vehicles, women in cloche hats and ankle-baring dresses gaze at city street corners where florists and grocers call to them. At night, cabaret performers take to smoke-filled stages, and in nightclubs, musicians dressed in suits complete with a flower in the buttonhole play jazz and tango. The legendary art cafe Mała Ziemiańska attracts experimental filmmakers, authors, and patrons of a nearby bookstore.

The end of the First World War brought Poland independence from both Russia and Germany in the form of the Second Polish Republic — and urbanizing Warsaw is flourishing. In this cosmopolitan cornucopia of contemporary art, it’s no wonder sizzling neon is about to become part of the transformation.

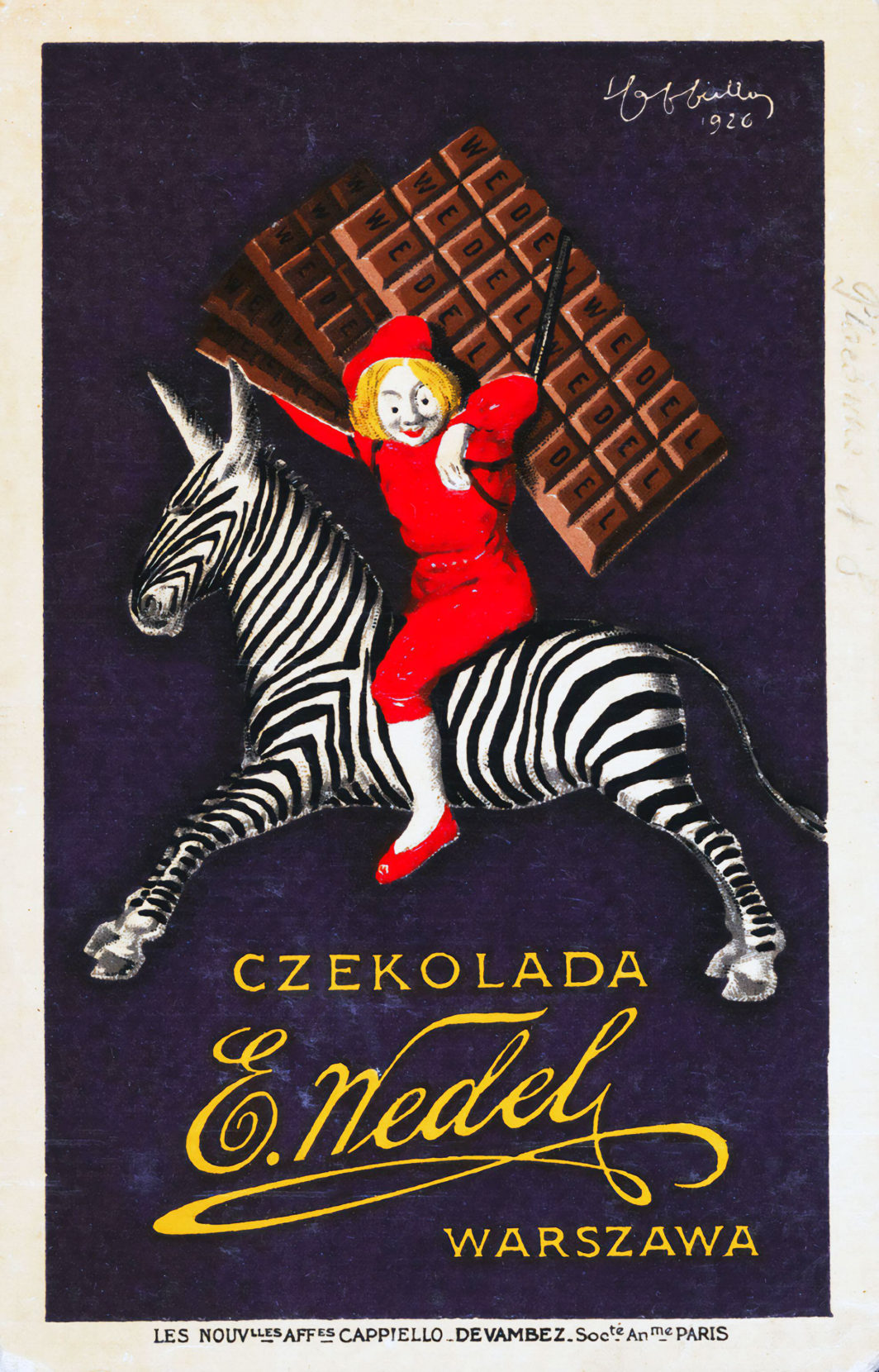

In the city center, Warsaw’s most famous chocolate brand, E. Wedel, sparks the trend.

Business is booming, and Jan Wedel, who has been in charge for three years, is about to put his stamp on the brand. The 51-year-old chemist grandson of the company’s founder has commissioned French-Italian cartoonist and poster designer Leonetto Cappiello to create an unforgettable advertising icon for E. Wedel’s chocolate lounge on Szpitalna Street.

This period marks the beginning of the modern era of advertising, and Cappiello is one of its initiators. Gone are the feminine pastels and the full-canvas feel of turn-of-the-century designs.

The swirls at the end of each letter were like an invitation, alive in hot orange.

When Cappiello’s neon icon is unveiled on the roof of the Wedels’s five-story building, it seems to add an entire story to the building’s height. A boy carrying three giant bars of chocolate on his back and riding a zebra made of glowing white neon illuminates the night sky and instantly becomes the electrifying image of the era. E. Wedel’s neon sends a wave of electricity through the city.

In the future, Cappiello will be known as the father of modern advertising. He creates bold, bright characters emerging from black backgrounds, which translate easily to the hot reds, oranges, blues, and yellows of neon displays popping out from a dark sky or set against a dark building. His designs capture the consumer’s imagination before the product addresses a need. But neon is more than advertising. It is a status symbol. And before long, dozens of shops in Warsaw will erect trendy neon displays, advertising drugstores and clothing shops, directing patrons into storefronts, and lighting the jazzing streets.

This Warsaw is not designed to merely be viewed. It is built to be seen. But it won’t be seen for long. This Warsaw won’t survive World War II, and its neon golden age will be lost forever.

But a new one will emerge.

Designed by Leonetto Cappiello, this neon ad for Warsaw’s most famous chocolate brand, E. Wedel, helped kickstart the modern age of advertising when it appeared in 1926. Photo: JJs / Alamy.

~~

On September 1, 1939, the skies rain down German bombs. Thunderous explosions shake the ground as tram tracks, nightclubs, chocolate shops, and fragile neon all succumb to the bombing. World War II has begun. Unbeknownst to the world, Adolf Hitler and Stalin have agreed to divide Poland between them.

The country is swallowed up in battles both physical and ideological, which only worsen when Hitler and Stalin go from allies to enemies. Millions of Poles are sent to work camps, concentration camps, and death camps.

By the time WWII ends, millions of Jewish and non-Jewish Polish civilians are dead, and nearly 90% of Warsaw lies in ruins. The teetering skeletons of bombed-out buildings are surrounded by mountains of debris, sometimes stories tall. Though their loss is nothing compared with the loss of life, the neon displays are gone. Despite Russia’s role in Poland’s years-long nightmare, the soldiers of the Red Army are honored by many as liberators, and so a Stalinist regime comes to power.

As the new communist government begins to rebuild Warsaw in the 1940s and 50s, a drab, icy gray washes over the capital.

Poles walk through the ruins of German-besieged Warsaw in 1939, at the start of World War II. Photo: Julien Bryan.

~~

Wandering the streets of Warsaw’s 1950s-era Marszałkowska Residential District in 2005, a gentle-voiced, London-based photographer with red hair and searching blue eyes, Ilona Karwinska, stopped in front of a graffitied storefront with her colleague, graphic designer David Hill. The thin concrete columns of the building were carved with idealized socialist icons of the working class: on one column, a sturdy, square-shouldered mother with her hand on the shoulder of her strong, broad-chested child, who carries a lunchbox; on the other, a brave young soldier, in a similar stance with a similar lunchbox.

Between the two reliefs, on the side of the building, a bright neon sign still glowed above outdated advertisements in the windows. A smaller sign, directly above the doors, buzzed too. Both billboarded the word BERLIN, cast in a curlicue font that screamed “circus!”

The two signs pulsed back and forth — first the large sign, then the smaller one. The shop was presumably unrelated to the German capital, but the swirls at the end of each letter were like an invitation, alive in hot orange.

Karwinska, who was born in Poland, left the country in 1991. The neon she discovered on her return 14 years later beckoned her back to an enchanting world she hardly remembered. “That’s when I began recording the last remnants of this extraordinary aspect of Cold War-era history, ‘neonization,’” Karwinska said. Her photographic project, Neon Warsaw, was born of this first encounter with BERLIN.

But two weeks later when Karwinska and Hill returned to the spot for a photo shoot, BERLIN was gone. What happened to those letters? she wondered. Where are the curlicues of those twin BERLINs? The project took on a creative urgency. Karwinska felt compelled to document as many of these dilapidated signs as she could, preserving them on celluloid before 21st century Warsaw destroyed them.

“Neons are like city haikus.”

Fortunately, she was also in time to save BERLIN. She called the owners of the store and learned they had removed the letters, shoving them into a jumble in their back room to await the scrap pile.

“We pleaded with the owners until they were eventually persuaded — possibly out of curiosity — to give us the sign,” she said. Those letters transformed her from an artist documenting the past to one resurrecting it.

“We started contacting the owners, shopkeepers, and scrapyards to urge them to save the signs,” Karwinska said. “It worked.”

Soon, Karwinska and Hill, her partner in neon, filled the balconies, courtyards, and storage cellars of all their local friends. But what to do with these piles of discarded letters and signs?

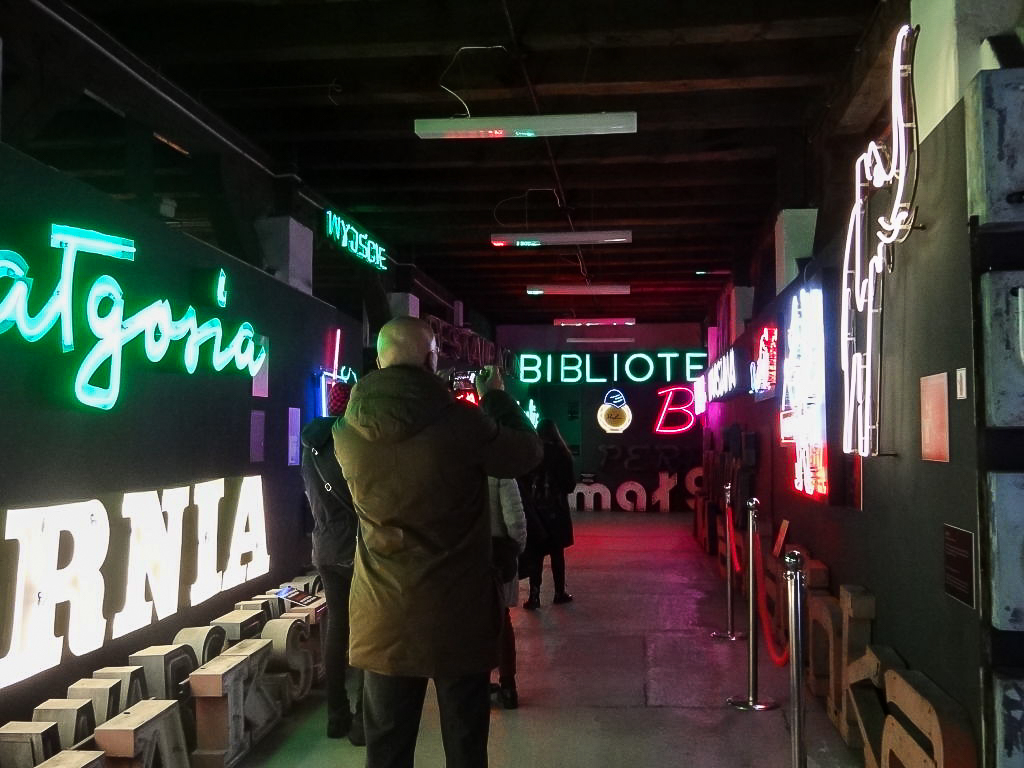

In 2012, their collection became the raw material for Warsaw’s Neon Museum.

I found my way there by wandering through a collection of brick factory buildings populated by trendy design studios and restaurants, then past a jumble of huge metal letters stacked outside a nondescript building. When I pulled open the door, the dim hum of bright lights greeted me, almost pulling me into the aisles of signage. With little overhead lighting, the walls glowed bright pink, red, green, and blue — a time capsule of art and advertising.

Warsaw’s Neon Museum is the only institution of its kind in Europe. Photo: Natalie Skrzypczak / Picture Alliance / Getty Images.

As I read the curated wall plaques, which detailed the history of the signs, I felt as though I’d stepped into their time and place. There was one sign in particular I wanted to know more about: BERLIN. I wanted to pick up the story where Karwinska had left off, but the plaque revealed little.

So, when museum employee Martyna Baranowicz asked if I had any questions, the history of BERLIN was at the top of my list.

“We saw the name of the company that produced the sign, so we took the sign back to them, and they repaired it,” Baranowicz told me.

BERLIN had been built by Reklama, one of three Polish companies tasked with producing neon in the Communist period. Designed in 1974, the sign hung outside Capital Textile and Clothing Enterprise on Marszałkowska Boulevard. Was this clothing store advertising textiles made in Berlin? Was it a nod to the international fashion industry? Was the unique font a bold rebellion against the conformity of communist design principles?

The modern technicians at Reklama just shrugged.

They didn’t know the sign’s history, but they knew how to repair it. They reconstructed the glass, bending it expertly with heat and using the metal housing of the old signs as a guide for the font and angles. Just as neon technicians had done with so many signs before, they created the glass in Warsaw and ordered the noble gases from neighboring Ukraine.

“It’s like completing a circle in time,” Baranowicz said.

This sign and its circus-y font inspired photographer Ilona Karwinska’s “Neon Warsaw” project — and indirectly laid the foundation for the city’s Neon Museum. Photo: Dave Stevenson / Alamy.

The star-like outline of a woman in short-shorts, stretching her hands overhead and her legs downward, soars next to the roof of a 13-story building at Plac Konstytucji. A circular object cascades down, down, down the side of the building, giving the impression that this woman is spiking a volleyball from rooftop to sidewalk.

The year is 1960. We’re well into the Communist era, and by now, several blinking neons ring the plaza, each telling a small story. A neon chimney puffs smoke up the side of a building. A series of illuminated circles lead to a central bulls-eye in the center.

The Volleyball Player — Siatkarka, in Polish — is the work of a graphic designer from the Polish Poster School, Jan Mucharski. Trained as an architect, Mucharski traveled in the 1920s to Constantinople and Paris as a spokesperson for Polish design. But years later, when he and fellow artists could no longer find clients for poster design and advertising during the war, they leapt at the opportunity for state-sponsored employment. Now Mucharski works in neon — craft and politics have landed him on the approved list of designers.

Although the postwar period led to some bleak design choices in Warsaw, Stalin’s death, in 1953, brought about the Polish Thaw, a period during which Poland’s own ruling Communist Party decided to reform its image and distance itself from Russia and Stalin’s brand of communism. A fresh, futuristic vision of the Polish People’s Republic (PPR) has taken shape in spirited signage, a process the Party calls “neonization.”

A nod to thriving, pre-World War II Warsaw, neonization is meant to inspire confidence in the vitality of the Eastern Bloc economy. The Publicity Program Committee is tasked with selling the idea of a “worker’s paradise” — the communist vision of economic, social, and aesthetic harmony — to the Polish people as much as to the outside world. And though the committee wants Warsaw to stand apart from the consumerist capitals of the West, it turns to popular designers, tested advertising methods, and “just-as-good-as-the-West” technologies to accomplish its mission.

Three designated advertising companies — Lumen, Reklama, and Spójnia — maintain the equipment needed to produce the signs. A government manual stipulates the appropriate fonts (to ensure visual clarity), colors (red for butchers, green for grocers, yellow for bakers, light purple for drugstores), and sizes (to harmonize with the architecture). This style manual has been passed on to the artists, graphic designers, and architects tasked with bringing to life the latest vision of the city.

This Warsaw is not designed to merely be viewed. It is built to be seen.

By the time a sporting goods store on Plac Konstuytucji asks the committee if it can install a neon sign, Mucharski is likely familiar with the architectural requirements with which he must comply.

Neon, for its part, has been rebranded as the lightbulb of the pragmatic utopia — tasteful, cohesive, and a practical form of propaganda for a mid-century communist metropolis. Yes, this is advertising — but advertising for communism, the PPR has concluded, is not really advertising at all.

When Mucharski’s design is complete, it is sent for final approval to the Chief City Designer, who ensures it does not clash with the city’s existing art and architecture, and does reflect a socialist paradise.

And so the white-and-red volleyball player illustrates pride in Poland’s athletes and sporting equality between genders. And if the volleyball blinking down toward the street also alludes to the shopping opportunity in the store below, then so be it.

~~

On an autumn night in 2009, the darkness of a Polish winter was fast encroaching. An audience gathered on the edge of Kępa Potocka Park, on the north side of the city, to witness the unveiling of a new work by the eccentric, mustachioed artist Maurycy Gomulicki. Against the distant backdrop of a few window lights in a drab apartment block, neon pink bubbles began to sizzle and pop. Tiny ones at first, then bigger loops and large circles, half seconds apart in an animated pattern. Finally, a soda-glass frame blinked alive, and then the swelling bubbles began their dance again. The crowd cheered, photographed, watched together.

Funded in part by an energy company, the 56-foot-tall structure, Światłotrysk — Lightspurt — was Gomulicki’s first and still his largest neon project in Warsaw.

“It is a monument of joy, symbolically and emotionally accessible to everyone,” he told me. Blinking seemingly at random, the suspended circles, popping like a carbonated beverage, enlivened the darkness.

“Polish culture is pretty gloomy and serious,” he said. “There is so much sorrow in it that we get used to glorifying the fallen heroes, victims, and tragedies. I respect that, but I do not want to live in a graveyard.”

Gomulicki’s playful style was a reaction to growing up in Warsaw in the 1970s and ’80s, when Soviet neon — much like the Soviet Union — was on the decline. At first, it was glowing red signs advertising bare-shelved butcher shops and light purple cosmetic icons above shuttered pharmacies. But the economic depression eventually cast an even grimmer shadow over the capital: To save money, businesses simply extinguished their neon.

The neon signs became a symbol of a failed system.

But that didn’t stop Gomulicki from admiring them.

“I am a magpie, so am keen on everything colorful and shiny,” he said.

In the early 2000s, he too began documenting neon signs for his project W-wa — a close-up photographic view of his transforming hometown.

“People started to be interested in our recent modernistic past,” he said, “but most of the efforts were focused on building archives and preserving the heritage. I wanted to use my Warsaw neon experience to create something new and vivid rather than only bow to the past.”

With Lightspurt, he began to do just that. Soon, he was neonizing anything he could, from beautiful restaurant logos and graphic titles to the iconic Warsaw mermaid, the symbolic defender of the city. Other artists soon followed with their own neon projects in the capital.

Modern neon works of art like Gomulicki’s bubbles bring a playful energy to Warsaw. Some are intended as advertising. Others simply enliven the sky. Triple-outlined blue and yellow letters below the Gdansk Bridge send a message in Polish to all passersby: Miło Cię widzieć — Nice to see you. A dizzying, squiggly red line loops and zags and spirals along the length of a dark 19th-century building. No words. Just light. And a simple red neon sign in a park reads, in English, “ALL THE THINGS THAT COULD HAPPEN NEXT,” in bold, block lettering.

“Neons are like city haikus,” Gomulicki says. They can be written anywhere, and their colors deny anyone the possibility of ignoring their message.

Neon letters spell out “Miło Cię widzieć” — “Nice to see you” — on the Gdansk Bridge. Photo: Euan Cherry / Alamy.

~~

By my third trip to Warsaw, in 2020, neon-spotting has become my favorite game. Around every corner, through the bleak tree branches, in the back of a shop, I wait for that jolt of light. Looking up, I see blue strips of oceanic neon swirl around a large globe. The red outlines of continents blink on and off. Above an office building, the world turns in style.

No matter how cold the weather, the visual frequency in the city seems to brighten the mood. I recall something Gomulicki told me about the role of neon in this far-north country: “Neon signs bring a sort of peculiar electric spring to the city landscape and serve as a nice remedy for the omnipresent melancholia. They look joyful and rich on the dark, rainy days.”

As I cross the chilling riverfront in the dark and encounter the glowing bubbles of Gomulicki’s design along the canal, I can feel his words. The bubbling circles not only brighten the sky but lift my mood as well. Art can do that to you.

Many of these resurrected neons advertise products and companies that no longer exist. But like that old BERLIN sign above the store, neon that outlives its function does not cease to be beautiful.

Below The Volleyball Player, the former sporting-goods store is divided into a restaurant and camera store. On an empty building, dizzyingly pink roses above the red lettering that used to advertise a drugstore are now simply a piece of cultural heritage in the city center. Both displays make me stop and stare.

“It’s like completing a circle in time.”

In each era, Warsaw’s neons were created with different intentions, but they’ve always been art. And, with a little luck and persistence, art lives on — through decades, through war, through the rise and fall and rise of nations.

And sometimes, art is a glowing boy carrying chocolate bars while riding a neon zebra. In 2018, nearly 100 years after it first lit the Warsaw night, the neon icon that started it all — restored by the Warsaw Neon Museum and E. Wedel — returned to the city skyline.

Walking along Szpitalna Street, I see him atop the building. And when I walk through the doors of the E. Wedel chocolate lounge beneath the resurrected neon, I find a display of Ptasie Mieczko, a unique chocolate-covered-marshmallow treat developed by E. Wedel in the 1930s. Whether to art, history, or confections, in this city, neon always leads me to the place I want to be.

A neon icon returns: In 2018, nearly a century after it sparked an advertising — and aesthetic — revolution, the newly restored E. Wedel chocolate sign glows again. Photo: Adam Stępień / Agencja Wyborcza.pl.

Emily Manthei

Emily writes words and makes films that explore subcultures and cultural paradoxes.