Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

This story has been republished in the Hidden Compass Legacy Issue in celebration of reaching 100,000 readers.

The marine fish landing site at Cox’s Bazar was pristine when Alifa Haque arrived, adrenaline humming. She got there before the sorting, chopping, and selling transformed the sheet of concrete tiles into a slick swirl of guts and mud.

The fishermen hopped off their rides into murky, ankle-deep water and lugged their catches up by the basket. They carried the fish under the landing’s roof and out of the sun, or laid them outside to dry along rows of raised wooden planks — so many thousands that the boards shimmered with scales.

Wearing pointed glasses with a pair of shades atop her brown hair, Haque squinted against the morning sun, scanning piles of hilsa, mackerel, pomfret, pompano, snapper, croaker, and everything else boats dumped on these banks.

Steam surged off the river as the sun climbed. Haque’s cotton kurta clung to her skin. The nearly all-male crowd of fishermen, boat owners, and traders were dripping with sweat, arranging fish and sliding knives down the bellies of sharks. In the back of the landing somewhere, an ice-making factory cracked frozen blocks into chunks with a clunk, clunk, clunk that invaded Haque’s skull like a migraine.

She got there before the sorting, chopping, and selling transformed the sheet of concrete tiles into a slick swirl of guts and mud.

A lecturer — and later, professor — at Bangladesh’s Dhaka University, Haque frequented one of the country’s largest fish landings in search of rare rays and sharks. Eventually, she would carry this research into her doctorate work in marine conservation at the University of Oxford. Standing in waterproof sandals amid the fray, waiting for hours alongside her cameras, tape measures, and box of instruments, she made small talk with the fishermen — reminding them of her presence, building rapport. How’s business today? How are your kids?

“It’s not that they would have stopped me,” she said, “but I needed trust.”

The moment she spotted a specimen she wanted to sample, Haque plunged into the fracas — bursting from her nook with gloves, scissors, forceps, tubes, and alcohol pads in tow. If she was lucky, she could take four whole minutes — though she could make do with one or two — to photograph a shark, measure its length and weight, cut off a sliver of flesh, and slip it into a tube of 98% ethanol.

Marine conservationist Alifa Haque works side by side the fishermen at the marine fish landing site at Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, where she gets mere minutes to examine specimens. Photo: Oliver Deppert / Save Our Seas Foundation

Each animal she inspected was another data point that mapped how many of each species are left, where they might live, threats to their environments, and how they might be saved.

But it was impossible to see every cartilaginous creature as they came in. So, she spent her afternoons at the processing center down the street, checking out what she’d missed. It’s a smaller, more intimate place than the landing, almost like a big shed, where traders lay out sharks they’ve just bought from fishermen, hack off fins, peel away skin, and leave the meat to dry.

In 2017, a trader’s carcass caught her attention, and instinct forced her toward him to ask for a slice.

The man said no. He was cagey, but Haque took a chance and offered to pay for the whole thing. She handed the man some cash and cut out a centimeter of the shark’s flesh, just enough to take back to the lab — such a tiny piece that he gave her money back when he realized she was done.

All she knew then was that this sliver might be from a bull shark, a dangerous but common presence in tropical waters across the globe — or it might be among the rarest finds of her life.

~~

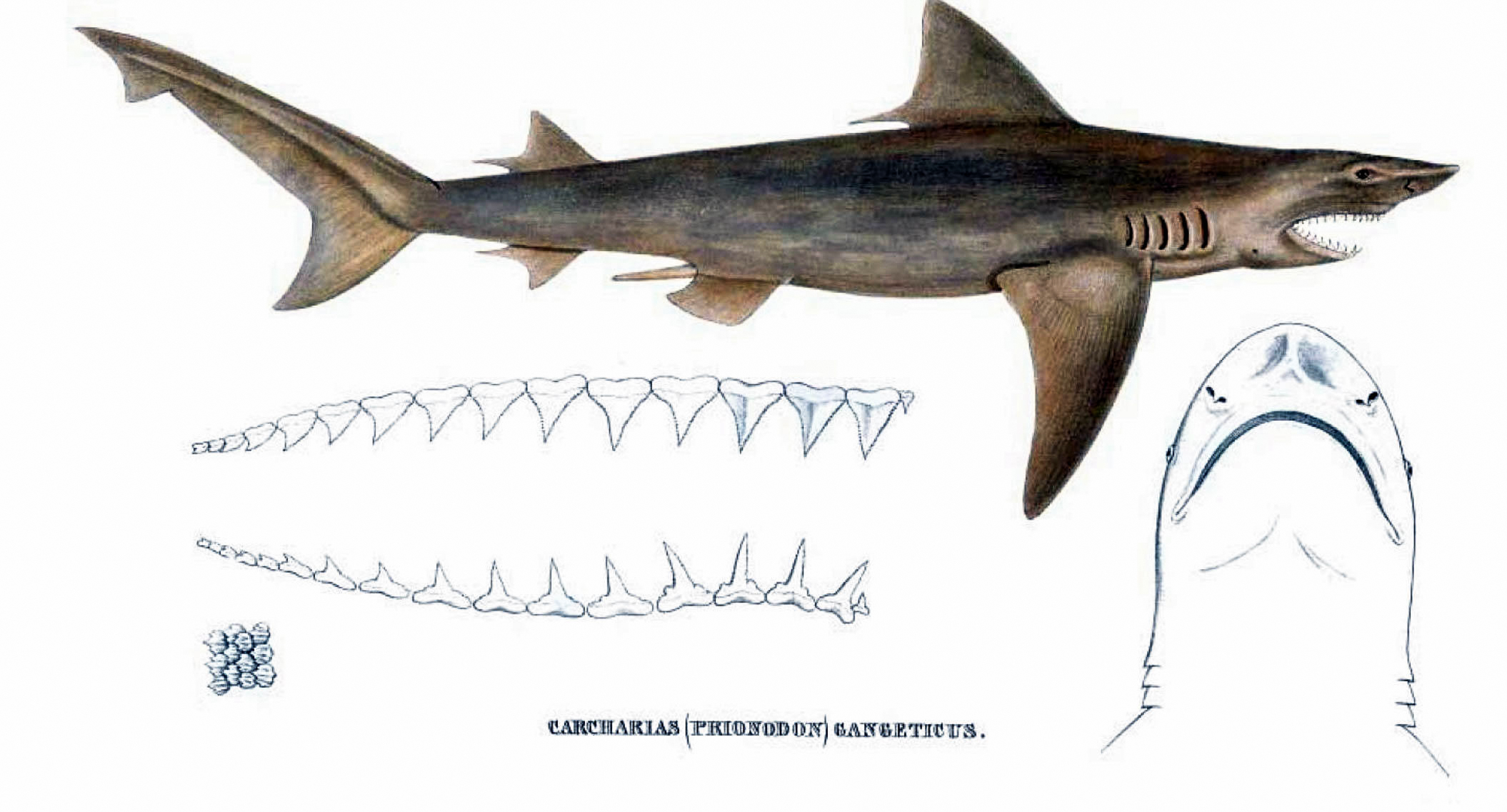

Glyphis gangeticus, the scientific term for what Haque suspected she had begged off that sour trader, has played host to a range of ironies and misconceptions since at least the 19th century, when the species was introduced to the Western world.

Our understanding of this creature is nearly as murky as the waters it swims in.

Ganges sharks, as they’re better known, might be one of Earth’s most endangered creatures, but they’ve also been called “a common groundshark in the Bay of Bengal.” Myth long held that they were man-eaters, but there’s no evidence the shark has ever attacked anyone (though it might munch on corpses floated downstream, following funeral rites). Murky gray in color, with a long, sharp tail, the creature looks a lot like a bull shark, which has a well-documented history of sticking its teeth into people.

Johannes Peter Müller and Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle sketched this illustration in 1839, when the German anatomists identified it as a distinct species. Photo: FLHC A22 / Alamy

Named after India’s holiest river, it’s doubtful Ganges sharks ever swam there, though the creatures are one of the few sharks that can feel at home in rivers for at least part of the year.

They spend much of their lives in water that’s about as opaque as a wall, and few scientists have ever searched for them. Anyone who does go looking has to navigate a sprawl of temperamental rivers and shifting coastline that mocks the existence of static maps.

In fact, it’s impossible to definitively say where Ganges sharks travel, because they’re rarely seen alive.

~~

On November 2, 1828, a Frenchman named Christophe-Augustin Lamare-Picquot set off from Calcutta aboard a boat loaded with notebooks for descriptions and crates for all the creatures he’d ship back to his motherland.

A pharmacist turned naturalist-traveler, he departed with a hired crew of 21 local sailors, hunters, and domestic servants, spread across two boats. The expedition steered toward the Sundarbans, a dense and expansive mangrove forest on the Ganges delta. Along the way, Lamare-Picquot stopped to recruit six more men, whose “English rifles and poisoned arrows” would bolster the white man’s cachet.

Navigating a boat in this wilderness was like sailing through a maze that kept changing its path. Creeks poured across muddy earth in the morning and vanished with the pull of the afternoon tide, as though sucked out by a giant straw. Islands surfaced and sunk like mirages. Sailors poked underwater with bamboo poles, wary of shallows that might run them aground. Oarsmen had to guide their vessels into narrow streams to escape the tidal bore, 15 to 20 feet high, that poured over the landscape every full moon.

Once the men hopped off into the forest, their boots surely plunged into spongy ground. Mangroves coiled tightly, obscuring their visibility like a cloud of smoke. Thick air draped over their bodies like drenched cloth. Three crewmen burned with fevers that could easily have been a symptom of cholera. Rhinos crunched through the thicket around them while pythons wound rivulets in the mud. Tigers snatched men who mined salt from the water, and crocodiles snapped up woodcutters chopping down mangroves along the stream’s edge.

After four days, Lamare-Picquot wrote, “my men were discouraged by the dreadful howls which the hosts of these forests uttered during the night.”

Rhinos crunched through the thicket around them while pythons wound rivulets in the mud.

By the end of the 42-day expedition, Lamare-Picquot had captured scores of animals, including a “royal tiger,” six monkeys of two different species, three speckled deer, five crocodiles, and a mother and baby rhino. Though he doesn’t mention it in his journal, he’d also caught an unusual shark.

This 1866 painting depicts Frenchman Christophe-Augustin Lamare-Picquot, who explored the Sundarbans by boat in 1828. Among the haul from that expedition included an unusual creature that was eventually identified as the Ganges shark, a lost-in-translation misnomer. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais / Thierry Ollivier

~~

The shark that Lamare-Picquot’s hired hunters pulled onboard made its way to a museum in Berlin. In 1839, it was identified in the West as a new species. Likely due to cross-language confusion about where Lamare-Picquot was at the time his men lugged it onto their ship, the shark was called “Ganges.”

The misnamed creature next appeared in dated records in 1867, and then it vanished — a strange feat for a shark that can grow at least a couple feet longer than an average adult human is tall. It would be more than a century before it surfaced again.

Our understanding of this creature is nearly as murky as the waters it swims in. Scientists have fleshed out our view with what, at times, amounts to educated guesses — and traced the sharks to the coastline or inlets around the Bay of Bengal, where their namesake river pours into its delta. Here, the sea threads into a vast mangrove forest known as the Sundarbans.

Corralling their lives around regions such as the Sundarbans, Ganges sharks are thought to slip upstream during the dry season, as the sea pushes into riverbeds emptied of fresh water, and return to the coast once monsoon rains flush the Bay of Bengal back into the open. This sort of versatility led it to depend on rivers in a way that their open-ocean kin do not.

Just before the new millennium, in 1996, the Ganges shark reemerged in scientific records. By then, India and Pakistan had split into two nations and fought a war that birthed a new nation along the delta: Bangladesh. The 129 years between sightings transformed and mutilated the Sundarbans.

Not quite water, not quite land, the region illuminates links between worlds.

~~

The Sundarbans of the 1800s was equal parts illusion and reality, an ephemeral landscape of constant reinvention. Rivers roared through thick mangrove forests and across squelching mudflats, pouring tons of silt onto open land and just as quickly washing it into the sea. Their routes whiplashed across miles of coastline like a wild hose dropped on a lawn. Entire lakes welled up when monsoon rains swamped the wetlands, fading into grubby marshes once the sun cut through the clouds.

It was a place entirely at odds with its newest colonizer, an empire obsessed with predictable efficiency in service of profit. The British claimed the Sundarbans in 1828, just as Lamare-Picquot was beginning his journey, and they started to engineer it into an ecological machine capable of speeding plundered goods out of India as quickly as possible.

Navigating a boat in this wilderness was like sailing through a maze that kept changing its path.

Fishermen in the Sundarbans had long dug canals in the direction that fish already swam, but British engineers raked across these channels, using ditch-diggers to carve waterways wide enough for ships. Woodcutters leveled swaths of mangroves, and other laborers scraped away mounds of silt. The colonizers worked on their most ambitious projects during the hot months that precede monsoon season, draining huge marshes as the sun did its best to keep the ground dry.

By the mid-19th century, the British had flattened and paved this soggy ground into a series of parks, docks, and roads that laid the foundation for the cities to come.

Cleared land in the colonial delta meant space for the increasing numbers of jute factories springing up across then-Calcutta in the 1910s and 1920s. Homeowners began to dry their own swampy tracts in order to build out their bungalows. Skylines became filled with columns of smoke-spewing chimneys. The governments of India, Pakistan, and eventually Bangladesh took over in the latter half of the century, presiding over Calcutta and Dhaka’s ever-taller high-rises.

It’s perhaps not a coincidence that the elusive Ganges shark, fine-tuned to live in transitional spaces, disappeared while a succession of governments and settlers wrestled its ecosystem into something more rigid than it had ever been.

~~

Two centuries on, a shark slithers through grungy waters, stirring up clouds of muck. Maybe she’s poking around for a spot to give birth to a litter of pups, or perhaps she’s waiting for an electric pulse to thrum off a nearby fish, pointing her in the direction of breakfast.

The river is shallower than in generations past, pushing her closer to the boats of the apex predators splashing and buzzing overhead. Her instincts tell her to love the cloudy water, surrendering her eyesight to her electrical sensitivity and piercing sense of smell. But her habitat’s waterways are now so crisscrossed with hooks, lines, and nets that she has to duck and dive around them as if she’s squirming past a series of tripwires.

The shark Lamare-Picquot’s men yanked from the water, this shark’s ancestor, would scarcely recognize this place.

The Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna delta is now home to around 200 million people, five times the population of California living in hardly more than one third of the space. Much of that terrain is made up of islands — a hundred or so on the Indian side of the Sundarbans alone — that may soon be engulfed by rising seas. Four of them have vanished in just the last 25 years.

India and Bangladesh have continued to build so many dams in the region that some of its rivers look like clogged drains. When water can’t flow into the Bay of Bengal, the silt it carries sinks to the bottom of the riverbed like sand filling up a bathtub, rather than replenishing a coastline eroding faster than any other shore on the planet. With less room in the rivers, water also spills onto tracts of stagnant marsh that get saltier as rising seas press the ocean inland. Even in the portions of river that flow as they should, arsenic, chromium, cadmium, and bleach bleed into the water, the probable sources being paper and concrete factories as well as nearby shrimp mills.

Rivers are likely vital to keeping Ganges shark pups alive, says Peter Kyne, a river shark expert at Charles Darwin University in Australia. That tracks with what is known about the elusive shark’s better-studied Australian relatives — two separate members of the Glyphis genus, whose common names are the speartooth shark and the Northern river shark.

It’s perhaps not a coincidence that the elusive Ganges shark, fine-tuned to live in transitional spaces, disappeared while a succession of governments and settlers wrestled its ecosystem into something more rigid than it had ever been.

Without documented sightings, researchers can only make conjectures that juvenile Ganges sharks follow the same course and swim into adulthood amid the relative safety of rivers. But Haque and her team spread across Bangladesh haven’t confirmed any pups in the five years she has been surveying.

That may be a sign of just how fetid and deadly those waterways have become.

Seen in this merging of satellite imagery taken in 1999 and 2000, the Sundarbans appears like an intricate tapestry. Here where the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna Rivers meet at the edge of the Bay of Bengal stands one of the world’s largest remaining tract of mangrove forest — a natural wall protecting the coasts of India and Bangladesh and providing a rich habitat for endangered Bengal tigers, hundreds of bird species, and an array of sharks and rays. Recent research shows that a quarter of its trees exhibit signs of declining health. Photo: B.A.E. Inc. / Alamy

~~

Back inside the fish landing at Cox’s Bazar, Haque stood by a tiny stall that was selling biscuits, betel leaf, and other snacks. She sipped a cup of morning chai, camera slung over her shoulder, a box of instruments at her feet. Fishermen walked by to toss a few bills to the attendant in exchange for cigarettes and their own quick sips of hot tea before they went down to the water. It was hard not to notice the woman with all the gadgets.

They asked what that tube was for, or whether Haque could snap a photo of them real fast. She introduced herself as a student, a scientist, or both; she told them about the creatures she was studying; she asked a few well-placed questions.

Do you catch the sawfish yourself? What happens to sharks that get tangled in fishing nets? Have you seen any big rays in a while? Did you used to see more?

Amid crowds of largely poor fishermen, Haque was initially a person everyone “looked at but didn’t talk to,” a woman of higher education and privilege from the capital of Dhaka, an eight-plus-hour bus ride away.

“I remember being irritated easily,” she said. “Like… I can’t enter the fabric of this society.”

But she paid for their tea and betel leaf; sometimes, she’s embarrassed to admit, she offered cigarettes — anything to keep them talking. Through these tales she got a sense of the fishermen’s lives and that of the creatures they rowed alongside. She could picture the number of sawfish, rays, and sharks that used to swim there.

She could also imagine the rapid decay of the world these men and animals share.

India and Bangladesh have continued to build so many dams in the region that some of its rivers look like clogged drains.

Over time, her tea stall conversations turned into longer, more formal interviews that would last well over an hour. Later, she talked with women in fishing villages, learning how they scrimped to prepare for small catches and managed households while their husbands spent two weeks on the water. She learned that trawling ships scrape out potential breeding grounds close to shore, leaving fewer fish for the next season.

Two years after she started going to Cox’s Bazar, Haque and some colleagues rented a boat so she could document how the men brought in their catch. Many men here believe it’s a bad omen for a woman to board their boat, so she planned to watch from a distance. But then a fisherman she knew pulled up next to her and asked her to jump in. She protested; he didn’t have to break the taboo.

“You are one of our own,” he replied.

~~

All she knew then was that this sliver might be from a bull shark, a dangerous but common presence in tropical waters across the globe — or it might be among the rarest finds of her life.

In 2019, two years after Haque sliced out her sample of the cagey fisherman’s catch at the processing center, she co-published her discovery — Bangladesh’s first record of the Ganges shark since 2006. Identifying the specimen meant meticulously comparing her G. gangeticus DNA to dry jawbone and tissue samples archived on an open-access database. It was only the second time a scientist anywhere had publicly documented the shark throughout those 13 years.

There’s no question that unregulated fishing is the threat that could most easily force the Ganges shark from mystery into nonexistence, but it’s also an industry that some of Bangladesh’s poorest people rely on. Haque has spent years alongside both these realities, building a data-collection network across the country’s coastline. She hopes to help turn fishermen’s ideas into sustainable policies that they and the government can agree on.

But without changes, the Ganges shark’s fragmented research lineage offers more than a hint at what could happen next.

~~

The dual possibilities for the Ganges shark represent the natural endgame of two very different types of exploration.

Haque’s way is more hopeful and also more difficult. Built on a deep engagement with place, people, creatures, and symbiosis, her style of inquiry culminates in an understanding of what broke and how to mend the pieces into a thriving whole. Maybe that leads to a limit on trawling, a deal between fishing villages and the government that helps those communities make money without plundering their only resource. And maybe it leads to a law that halts the damming of rivers so those rivers can once more slip out to sea.

It’s not a vision that Haque or anyone expects to happen in a few years — plus such agreements would have to be enforced, which would be its own battle — but the shark’s habitat is under so much manmade pressure that a touch of relief might be enough to signal the region’s potential. A partial trawling ban could flood the rivers with more fish than anyone has seen in a decade. Drawn by shoals filled with bite-size meals, Ganges sharks could once again root out river nooks where they can give birth to a new generation of pups, whose path out to the Bay of Bengal looks difficult, but possible.

And then there’s Lamare-Picquot’s brand of exploration, the kind that grabs at whatever is within reach and razes everything else in pursuit of what is not, the kind that cuts down all paths that might have been.

Perhaps a 22nd-century scientist will read about this creature and get curious, never having heard of a shark named for India’s legendary river. Maybe she’ll set out to record the first sighting in over a century — only to realize that the gap she’s trying to close is actually the endless white space that follows the last words of a story.

###

In the two years since publication, Haque’s work in shark and ray conservation has been recognized with awards and fellowships from Edinburgh to New York City. The Ganges shark, if you’re wondering, has yet to make another known appearance.

Colin Daileda

Colin Daileda is a journalist in Bengaluru, whose work has appeared in Atlas Obscura, Longreads, and others. His latest for Hidden Compass is part of a series on humanity’s evolving and often confrontational relationship with water, and is supported by the Pulitzer Center.