Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

Muscat, Oman, 4.a.m. Minarets twinkled in the sable sky as I set out from the airport in a rental car, headed for the pink beaches and golden cliffs of Al Wusta. I could have been driving into the pages of Arabian Sands, for all I knew about the place. No internet listicle nor Instagram influencer had lured me here. I had come, in part, for just that reason: because viral content about this place didn’t exist. At least not yet.

Driven by a sense of exploration, I immersed myself in this place where everything was the color of dust and the air smelled of frankincense and myrrh. Among its vast deserts, barren land, and little infrastructure, Oman invited me in to take a seat. Strangers in dishdashas welcomed me into their homes for karak chai — black, milky tea flavored with cardamom, saffron, and sugar. From the courtyard of one of these homes, I watched the sun set and the sky glow a fierce orange I had never seen. “In Oman, travelers are guests,” my host told me.

The year was 2015 — halfway through a decade that transformed me both as a traveler and as a writer.

~~

As a wide-eyed Californian with a vocalized case of wanderlust, I used to believe that traveling was itself a noble action. I’m a woman who often travels alone; my presence in a place — and my writing about those experiences — makes a statement about every person’s right to movement. I sought opportunities to provide a counterpoint to Western prejudices about “exotic” or “dangerous” places. I took pride thinking that my work broke down barriers and dispelled myths. Taking a cue from writer Paul Bowles in The Sheltering Sky, I belonged “no more to one place than to the next.”

These ideals are what led me to journalism. Tucked in my backpack, weathered tomes by Bowles as well as Joan Didion, Paul Theroux, and others served as my first travel guides. A well-told narrative could take me along with these writers — the great observers of the world — and inspire my actions as well as my approach. Like Didion, I believed “that something extraordinary would happen any minute, any day, any month,” if only I went out into the world and found it.

But over the last decade of my career — in the pre-pandemic times — a new article format became insanely popular: the listicle, a digital list-article hybrid that is almost always topped with such FOMO-inducing headlines as “10 Best Places to Travel This Year” or “The World’s 5 Most Exciting Destinations.” These types of articles began crowding out assignments for the narratives that had moved me. But I adapted. Soon, the listicle was sending me around the world — and propelling my career.

Reporting these lists afforded me the ability to see the world, so I accepted each project with a mix of resentment and excitement. Celebrating the “best” a city had to offer, I reasoned, would inspire people to follow the gospel of travel.

~~

Moving through the world at a whiplash pace, I spent a year residing in Airbnb rentals in 14 countries, living momentary lives in residential neighborhoods, feeling halfway between traveler and trespasser. On assignment in Barcelona, I raced through tabernas and gin bars until my palate was numb. In Venice, I had four days to hit 13 gelaterias, 16 bars, 10 museums, and five hotels. I was to choose the best spots and write them up in a series of listicles.

The listicle reduced once complex experiences to bulleted guideposts: what, where, why. Within this context, deviation isn’t an option. Narrative gets lost in the margins.

By now I was well-versed in the formula: a mix of classics, hidden gems, and trendy spots that cleaned up nice in photos, categorized by verbiage that made scrollers want to click: 7 Must-Try Gelaterias, 10 Don’t-Miss Venetian Bars. During the editing process, keywords would be added to optimize search engine results. The worth of the writing was defined by its click-ability: Every article’s aim was, above all else, to go viral.

In his 2007 manifesto about “contagious media,” Buzzfeed founder Jonah Peretti glorified content boiled down to “the simplest form of an idea.” As this new standard spread through the travel media landscape, the listicle reduced once complex experiences to bulleted guideposts: what, where, why. Within this context, deviation isn’t an option. Narrative gets lost in the margins.

Yet the farther I ventured — and the deeper into the listicle trenches I got — the more I understood that traveling requires more than a suitcase and a checklist. I wasn’t just falling into the trappings of tourism; I was helping to set the trap.

~~

Pre-pandemic, local displeasure with over-tourism in the Portuguese capital reached larger-than-life heights. Here, a mural in the Lisbon neighborhood of Mouraria turns the notion of painting the town red on its bearded-hipster head. Photo: Gary Kinsman.

In 2014, I found wonder around every corner of Lisbon as I ambled its quiet calçada streets. At that time, encountering another American traveler there was rare. “Why not go to Spain?” perplexed locals asked me.

I didn’t say it was because Portugal had the makings of clickbait gold: Old World charm, photogenic vistas, and a quiet but promising restaurant scene. I fell for the country’s melancholic spirit, over-salted seafood and buttery pastéis de nata, and the feeling of being stuck in an era that predated social media. Back home, I wrote several stories saying just that, including one that appeared on the cover of a national travel magazine.

In the years to come, out of what seemed like nowhere, Portugal emerged as one of Europe’s trendiest destinations, appearing on many where-to-go-now lists. Tourists increased from 6.8 million in 2010 to 18.2 in 2016. I returned in 2018 to find the walls of Lisbon’s stone parishes and fado bars tattooed with bitter sentiments such as “Tourists, go home.”

My wanderlust was eclipsed by guilt. To accommodate the hordes of visitors, apartments were converted into Airbnbs by the thousands, causing tourists who wanted to “travel like a local” to displace actual locals. Selfie sticks crowded every scenic viewpoint in Lisbon.

Standing on the shore of the Tagus River, I gazed up at the Padrão dos Descobrimentos, a hulking limestone monument that marks the spot where, six centuries earlier, fleets of ships crept off toward Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Looking at the figures leaning toward the bow of a masted ship — led by Prince Henry the Navigator, whose dispatches launched the Atlantic slave trade — I recognized their romanticized ideal of travel and the impact often left in its wake.

In a way, Portugal’s history was boomeranging back to itself. In his 1978 book, Orientalism, Palestinian American writer Edward Said critiqued early exploration by the West. He wrote, “For even as Europe moved itself outwards, its sense of cultural strength was fortified. From travelers’ tales … colonies were created and ethnocentric perspectives secured.”

With international travel more accessible than ever before, more and more people were jetting off to places championed in listicles. But how many travelers acted like guests, rather than occupiers? How many judged their experiences by their hashtags? And what responsibility falls on the travel writer whose stories get the most clicks?

~~

After Lisbon, a batch of assignments sent me in search of The Best Hotels in Belize, The Best Canal Tours in Copenhagen, The Best Food Trucks in Austin. So when I landed in Siem Reap, I did what came naturally: I turned to the internet for a listicle that could summarize the city’s highlights and help me make the most of my limited time in Cambodia.

The three days that followed unfolded like a sad scavenger hunt. A sunrise tuk-tuk tour shuttled me through the temples of Angkor Wat. By nightfall, I drank cheap beer at stale pubs where black lights cast shadows on patrons showing off photos of elephant rides and trips to the killing fields. At a loungey art cafe, I found myself surrounded by other travelers with the same furrowed brow, fervently scrolling their smartphones — no doubt looking for a clue to uncover the real Siem Reap.

I returned in 2018 to find the walls … tattooed with bitter sentiments, such as “Tourists, go home.”

Desperate for connection, I signed up for a Khmer village visit billed by my hostel as “A Day in the Life of a Cambodian.” A guide picked us up in an air-conditioned van and drove us into the Siem Reap paddies, reciting a script about village life and the rice harvest. My fellow tour goers and I took turns snapping photos with a sickle, climbed into an oxcart for a bumpy ride, then got shepherded awkwardly through a local home by a family who showed us their bedroom and laundry drying on the patio as if on exhibit.

These real people were staging their lives for a small payoff, and foreigners looking to shore up cultural cred were buying the charade. Without a meaningful exchange, the experience was purely transactional. In Cambodia I wasn’t a traveler or tourist. I was a consumer with a passport.

~~

Oman was different. Without a list of “musts” to dictate my trip, my days flowed naturally, like the shape-shifting sands of the Arabian Desert. Arriving without expectations, it turned out, freed me from the tyranny of an itinerary.

I camped on random beaches, where dolphins arced out of the emerald Arabian Sea, and awoke to the muezzin’s call to prayer. I followed a dirt road to a village of jewel-box homes and pomegranate plantations high atop Jebel Shams. I found myself at a goat auction and got lost in a centuries-old souk filled with silver khanjars — traditional Omani daggers. I ate pit-barbecued goat with my hands at a roadside restaurant.

Opening myself up to Oman and its people encapsulated what travel can be: pure magic.

After my trip, I wrote several narratives about where Oman’s roads took me. Most importantly, they led me to discover just how little I understood about this place and the people in it, the way the world works, and even about being a respectful guest.

~~

I reached a critical juncture in my journey two years ago, upon landing in Kathmandu.

Three years after a devastating 7.8-magnitude earthquake, the city was still reeling. Broken statues of Hindu deities splayed out like a sacred jigsaw puzzle, surrounded by teams of people piecing the gods back together. In the streets, residents hauled sacks of cement mix over their shoulders and carried bricks wrapped in scarves. Artisans in their workshops hammered out bronze Buddhas to fill nearby temples.

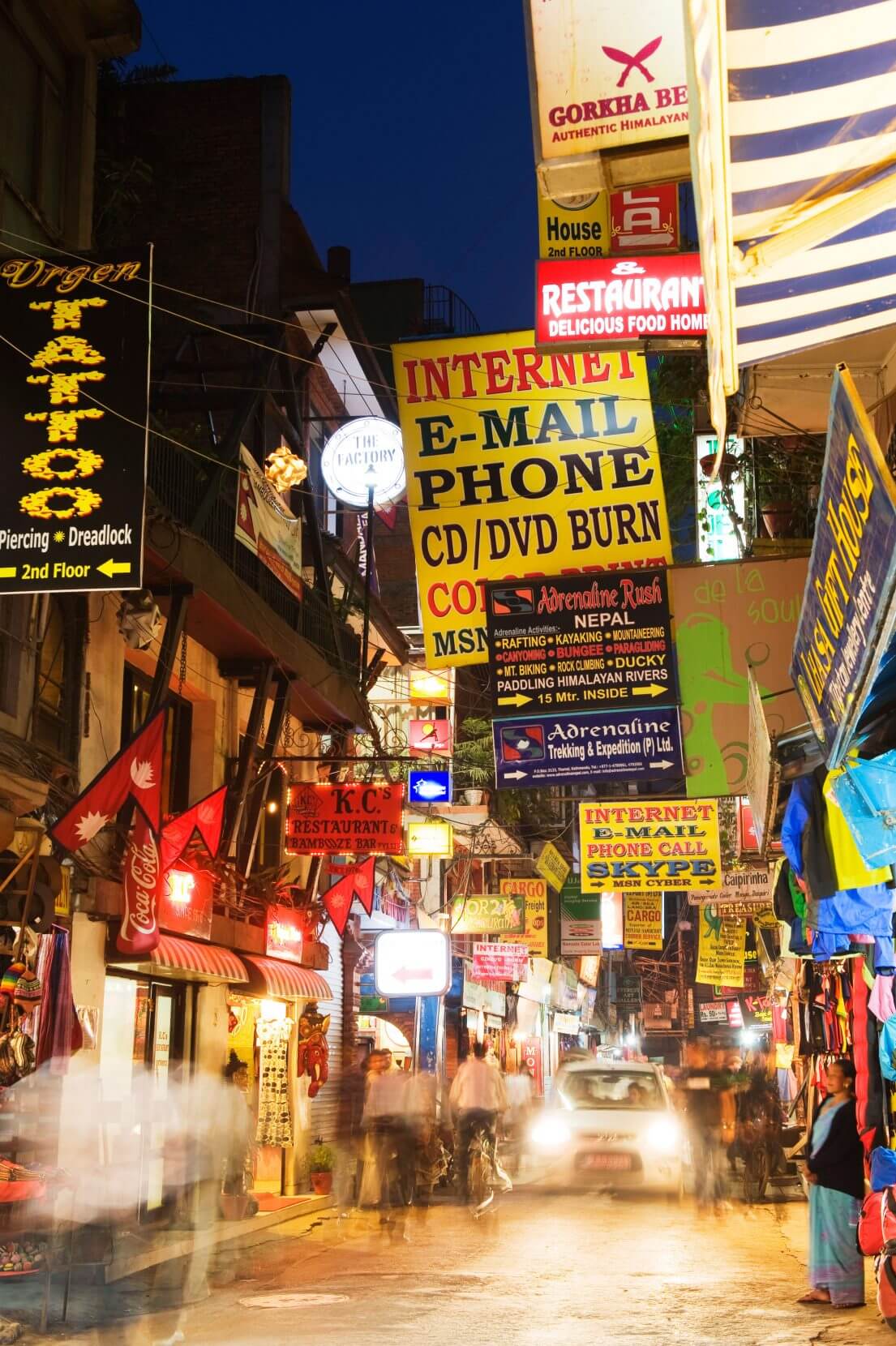

As I walked through Kathmandu’s Thamel district, a dichotomy emerged in stark relief: Foreign backpackers stocked up on pricey climbing equipment at flashy gear stores, while locals scavenged through rubble for scraps with which to rebuild their homes.

Founded as the site of an 11th-century Buddhist monastery, Kathmandu’s Thamel district has become a neon-lit tourist center extolling the virtues of foreign consumerism. Photo: Christian Kober/Alamy.

For decades, foreigners have exoticized Nepal as an “ultimate” destination, with Mount Everest as the peak must-do. In 2019 Nepal issued a record 381 climbing permits to foreigners set on claiming the world’s tallest mountain — adding up to 891 total climbers that year. Not everyone makes it: More than 300 climbers have died on the slopes since 1921, according to the Himalayan Database of expedition records. About a third of those fatalities have been Sherpas.

Ecuadorian travel writer Bani Amor points to colonialist attitudes as a driving factor of the bucket-list climbing of Everest, writing, “Over-tourism on this sacred mountain can’t be addressed in a vacuum: It is inextricable from Nepal’s current climate crisis, from the exploitation of the Indigenous Sherpas of Himalayan mountain communities, and from the man-vs.-nature complex that has long captivated white adventurers.”

Foreign backpackers stocked up on pricey climbing equipment at flashy gear stores, while locals scavenged through rubble for scraps with which to rebuild their homes.

The dissonance of Nepal exposed for me the danger of the listicle. Embedded in the structure of the list is a desire to conquer. Travel is presented as something to be achieved, or dominated. When this conquest mentality meets the reality of over-tourism, the world’s most vulnerable populations often pay the consequence.

~~

When borders snapped shut in March 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic, I found myself in perhaps my most foreign experience yet: standing still. From the balcony of my apartment in Istanbul, where I’ve lived for two years, I watched the usually busy sky suddenly go quiet.

With the world sheltering in place and anxieties swirling, I saw one bright spot on the horizon: The listicle went on lockdown, too.

Just as all those years ago in Oman, I find myself hoping the darkness of this night will foretell of a bright dawn ahead — one that illuminates the many paths that await us. But that will only happen if, when it’s time once again to move, we make the choice to click into our intuition and choose storylines vast enough to reflect the complexities of the world.

Only then will I deserve the hospitality of people who patiently tolerated my missteps, and still welcomed me as a guest and invited me into their homes for tea.

Jenna Scatena

Jenna Scatena is an independent journalist based in Istanbul and San Francisco, whose work explores the intersection of place and culture.