Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

Buried beneath the floor of the Mediterranean, in waters so turbulent the epic poet Homer had imagined the thrashings of sea monsters, the ship waited. She had once defended an ancient settlement near modern-day Marsala, Sicily — until she was sunk in a dramatic battle during the third century B.C.E. For two millennia, people passed by her, unaware. As time wore on, the sea and its banks shifted, until water just deep enough to submerge a person stood between the vessel and its reclaimed glory. Yet her hiding place wasn’t the ship’s only secret: Her timbers held a clue to history.

Finally, the currents of circumstance brought a pair of unlikely rescuers to her side.

First came Honor Frost, a ballet set designer turned deep-sea diver who was destined to pull back the curtain on sunken treasures. In the early 1950s, Frost found herself alone in the dark depths of the Mediterranean, clinging to a rope as she slowly descended to a Roman shipwreck off the coast of France. Eventually, 50 feet underwater, she saw her prize: a wonderland of ceramic amphora jars. Before long, she was hovering at the bottom of the sea, surrounded by relics from the ancient world. So began her decades-long obsession with shipwrecks.

Then came the winemaker. In 1951, Pietro Alagna began presiding over a generations-old vineyard in Marsala within sight of the ink-blue sea. He was carrying on his family’s legacy, harnessing the blistering sun to cultivate grapes high in sugar, and producing rich, aromatic wines. Driven by a thirst for knowledge and a generosity of spirit, the Sicilian businessman entered the scene as a curious bystander.

In time, more than just the sea would connect their stories.

~~

For most of the history of modern archaeology, underwater excavation was considered scientifically impossible. As “gentlemen divers” gave the emerging sport of scuba diving a shot in the mid-20th century, they sometimes discovered and explored Roman shipwrecks, as fishermen and sponge divers had before them. If these divers found anything that seemed interesting — an anchor, a sculpture, a clay amphora used to transport wine or olive oil — they would wrestle the object from its surroundings and bring it to the surface for study, often destroying parts of the wreck in the process.

On land, archaeologists tried to make educated guesses about these objects. But since the items were divorced from their context, these archaeological “findings” were mostly just conjecture. This was deemed unfortunate, but inevitable; the mechanical challenges of excavating underwater were too difficult to overcome.

Frost believed otherwise.

~~

By the late 1950s, Frost had built on her love of diving — and of the ancient wonders of the deep sea — to begin forging an entirely new discipline: underwater archaeology. The summer of 1971 brought her and a team of international archaeologists to the coast of Marsala. They were lured to a lagoon there by the lore of a famous sea battle in the third century B.C.E., and by the discovery of potentially ancient ship timbers by a local boat captain.

Buried beneath the floor of the Mediterranean, in waters so turbulent the epic poet Homer had imagined the thrashings of sea monsters, the ship waited.

They camped out in a former police barrack with no electricity or running water, and searched for sunken ships in a 26-foot fishing boat, its faulty motor spurting and sputtering its way around the lagoon.

For weeks, they searched in vain. Frustrated, the team decided to dock the boat and try a rudimentary survey method. They spread out evenly in the water and advanced to scan the sea floor in unison. Their photographer broke rank to retrieve a marker that had floated away. Before returning to the group, he signaled a find. Frost later wrote in the field report that she thought he was too far off course to have discovered anything significant. She was reluctant to answer his call.

But when she joined him, she later wrote, “A large timber … emerged from the sand like the head of a primaeval animal crowned with weed.”

~~

In 241 B.C.E., the naval Battle of the Aegates raged off the coast of modern-day Marsala, Sicily, as depicted in this historical illustration. The battle ultimately gave the Romans a decisive victory in the First Punic War. Photo: FALKENSTEINFOTO/Alamy.

Marsala’s first inhabitants, the Phoenicians, arrived in the vicinity during the eighth century B.C.E. For the next few centuries, Roman ships battled the Phoenician fleet for control of western Sicily and Marsala’s adjacent lagoon, which — at just 123 nautical miles from Tunisia — offered strategic trade access with Africa.

At times, massive, oared ships from one fleet managed to maneuver around the side of an enemy vessel and ram that vessel’s hull until it sank, while men threw themselves over its sides to avoid getting pulled down with the wreckage. Other times, rowers would remove their circular shields from holders along the side of their ship, take up their spears, and fight hand-to-hand on the ship deck.

For centuries, the Phoenicians’ superior shipbuilding talents gave them the upper hand against Rome. But in 261 B.C.E., the Romans captured a Phoenician warship and copied it, building an astonishing 100 replicas in just two months, according to writings by Roman naval commander Pliny the Elder. On March 10, 241 B.C.E., Rome finally outmaneuvered the Punic ships during a dramatic battle that forced the Phoenicians to surrender Sicily.

More than 2,000 years later, naval historians still didn’t know how the Romans had produced so many ships so quickly — a remarkable feat of engineering for any time period, much less antiquity.

~~

Frost was the kind of rebel who, shortly after World War II, sunk herself to the bottom of a pitch-dark well in England on a lark, as a crowd of revelers looked on from the garden. With 20 feet of black water above her, Frost wore a type of diving suit developed during the war, inhaling air through a mouthpiece attached to a hose that led to a pump at the top. In her writings, she called the impromptu initiation a “baptism.”

Born in Cyprus in 1917 to wealthy British expats and orphaned at a young age, Frost studied art at boarding school in Switzerland, and at university in London and Oxford, where she began running in artistic circles. She always followed her own rules: During World War II, she drove a fire truck and spent six weeks wedded to an Army captain, before the pair separated and she swore off marriage forever.

In the late 1940s, while in France, Frost came upon Jacques Cousteau’s newly formed Club Alpin Sous-Marin, one of the world’s first scuba diving clubs. She convinced Cousteau’s colleagues to teach her to dive with their new Aqua-Lung. Soon, she was spending as much time as she could traveling around the Mediterranean, in search of undersea wonders.

“One never loses the thrill of breaking past the surface and penetrating another world,” she wrote in her 1963 book, Under the Mediterranean.

After a few years, Frost’s travels and her design background presented her with an opportunity to work as a technical illustrator for excavations in Palestine and Lebanon. Armed with expertise in diving and knowledge of archaeological survey methods, she was sure — despite the misgivings of the era’s leading experts — that rigorous scientific excavation was possible underwater.

In 1959, she helped organize a groundbreaking proof-of-concept mission on a Bronze Age wreck in Turkey. The expedition would go down in history as the first example of underwater archaeology performed to exacting technical standards.

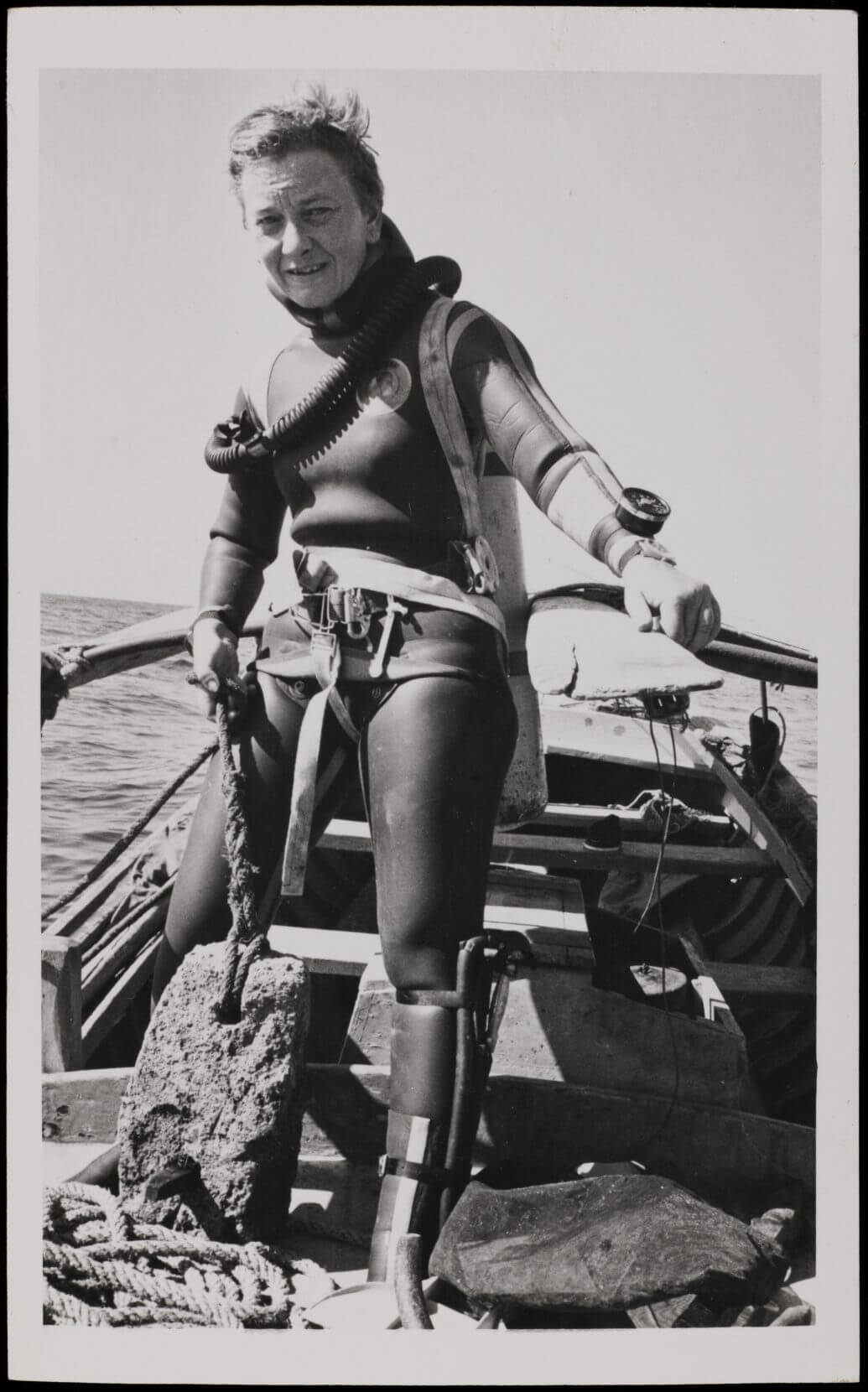

Beginning in the 1950s, pioneering underwater archaeologist Honor Frost championed stone anchors as a tool for understanding shipwrecks. She became known as the “Lady of Anchors.” Photo: Honor Frost Archive, Special Collections, Hartley Library.

~~

In Sicily, Frost found herself on the cusp of another breakthrough — but without the support she needed to keep her mission afloat. Through a mutual friend, she connected with a local benefactor, Pietro Alagna.

Alagna ran Cantine Pellegrino, a winery founded in 1880 by his great-grandfather at the height of Marsala’s historic wine boom — just over a century after a British merchant had happened upon Marsala while seeking shelter from a violent storm. While waiting out the waves at a local inn, this seafarer had sipped a strong local wine made from a revolving batch of mosto — grape skin, seeds, and juice. It wasn’t clear where one vintage ended and another started: vino perpetuo, or perpetual wine, the locals called it. So enamored with his discovery, the merchant shipped fifty 100-gallon barrels of the drink back home to England, fortified with brandy for safe passage. Marsala wine, as it quickly became known, was an instant hit. By the mid-20th century, Cantine Pellegrino had grown a family fortune.

Alagna didn’t know anything about archaeology, but, like Frost, he loved history and had an insatiable sense of curiosity. He wasn’t entirely sure how to help, but at least he could get the archaeologists out of the police barrack and provide logistical support. Little did he know how his role would evolve.

~~

The shipwreck that Frost’s team uncovered in 1971 had probably only recently been exposed — perhaps by a sand dredge — and was not likely to survive long. The vessel was threatened both by oxygen and the churning, unpredictable sea. The next big storm could either tear apart the hull and sides, or wash the ship away entirely — never to be found again. The excavation quickly became a rescue mission.

“A large timber … emerged from the sand like the head of a primaeval animal crowned with weed.”

After evaluating the wreck underwater, they would need to raise the entire ship, piece by piece.

News of the discovery quickly spread throughout Marsala, from its elegant piazza and the twin bell towers of its columned church, to the back roads linking coastal wineries, where the scent of fermentation hangs in the air and grapevines glow near-yellow under the heavy sun.

Residents were astounded by “having the fortune to star in one of the greatest pages of the history of archaeology in the Mediterranean, if not the world,” a member of the Lions Club wrote.

The goal was to preserve and reassemble the ship for future generations to study and admire. But first, Frost’s team needed to build freshwater desalination tanks to store the ship’s pieces — otherwise the wood would dry out and disintegrate on land. Once leached of salt, the wood needed polyethylene glycol, or PEG. The ship’s porous wood would absorb this hot wax and harden like plastic, an essential step for the ship to be put on display.

Alagna had never met anyone like Frost, but they quickly bonded over art, music, and history. Hooked on the intrigue of it all, he provided Frost’s team a villa outside of Marsala, equipped with living spaces for archaeologists, and warehouses to store equipment. His workers built desalination tanks on the property to store the ship’s pieces as they were pulled, one by one, from the water.

From 1972 to 1974, Frost supervised an expedition filled with painstaking excavation work — measuring and recording every detail of the underwater site — followed by grueling, 12-hour days battling high waves to raise heavy lumber. She became a well-known figure around town, with the community carefully following the project’s progress. Locals invited her into their homes for breakfast. The police looked the other way when she parked in prohibited zones.

In the summer of 1973, she was determined to finish the recovery, but beset by “acts of god” — including two members of the crew falling ill, high winds and currents, and equipment failure — the season proved to be both “a torment and inconclusive,” she wrote to a colleague in Rome. But when others may have wavered, Frost stayed the course.

In the field report, she wrote: “The wreck had become my ‘Moby Dick.’”

~~

A series of unfamiliar markings trailed down the ship’s hull. This detail tantalized Frost and her team, and they called in an expert in ancient script. His findings added to the excitement: The ship was inscribed with letters from what is often called the world’s oldest alphabet, Phoenician. It was a shipwright’s ancient instructions on how to assemble the pieces.

At long last, these markings solved the centuries-old mystery of how the Romans had built so many ships so quickly after capturing a Punic vessel. If the Punic ships were prefabbed and then assembled, the ship markings would have revealed their mass-production techniques to the Romans, who could then copy them to finally gain the upper hand at sea.

So extraordinary was this revelation, the powerful Italian National Research Council agreed to oversee the last phase of the project.

But just as the time came to start chemical trials and remove the wood from Alagna’s desalination tanks, the council’s experts concluded they didn’t know how to do the work. Preserving ancient ships was a nascent discipline. Without the PEG treatment, all the years spent fundraising, obtaining permits, and raising the ship would go to waste. The ship, having survived two turbulent millennia beneath the sea, and a precarious recovery to land, would simply crumble.

~~

With Italy’s largest public research institution at a loss as to how to save the ship, the mission was at risk of disintegrating.

But after years providing logistical support, Alagna noticed something: Wood preservation wasn’t all that different from fermentation.

Complex chemical reactions, rich in biodiversity, determine the flavor, aroma, and even the deep, opaque color of Marsala wines. Throughout the process, vintners carefully control the temperature to allow certain yeasts to thrive and others to die off as the alcohol content rises. Alagna’s degree in agriculture, combined with years at the cantina, gave him a unique skillset.

He could draw from his knowledge of chemistry and organic processes to help save the ship.

~~

News of the discovery quickly spread throughout Marsala, from its elegant piazza and the twin bell towers of its columned church, to the back roads linking coastal wineries, where the scent of fermentation hangs in the air and grapevines glow near-yellow under the heavy sun.

Alagna is 92 years old and a bit deaf. He sits at a wooden table in his spacious office on the family winery’s ground floor, his white jacket — like a lab coat — over a sweater vest, his thin, white hair carefully combed back from his temples. As he begins describing his decades-long relationship with Frost and the Punic ship, his younger self emerges, an old-fashioned problem solver.

“All you had to do was desalinate the wood in water, and then gradually add the PEG and heat the water,” he says.

The challenge came in achieving the necessary precision. “I put the wood in a stainless steel container, and then this was regulated with a thermostat, gas heating, a burner — basically assembled the same way we do in the wine sector,” he explains, his voice refined but gruff. He is no longer used to talking for long stretches.

He proudly tells how his workers at Cantine Pellegrino built the tanks and equipment anywhere they could find space — in the wine cellar, the mechanics shop — and when that wasn’t enough, they created a special warehouse and built more tanks there.

The preservation lab they built was so advanced that ultimately, the director of the Central Institute of Restoration in Rome came to study it. A preservation expert visited periodically to monitor and adjust the settings. After nine months, the ship was ready to be reassembled and displayed.

Half a century later, Alagna describes the feat as the “greatest adventure of my life.”

~~

But the effort, it seemed, had been too successful. The regional government announced a decision: The ship would be housed at a museum in the larger, more prominent city of Palermo.

The people of Marsala were devastated.

With “a heavy heart,” Frost wrote to a friend, she “returned to Marsala to prepare for the immediate removal of the first batch of ancient wood.”

On July 27, 1978, a moving truck arrived at the Cantine Pellegrino to load up the ship’s pieces and transport them to Palermo. Suddenly, word spread that there was a commotion at the Cantine. One of the town’s residents had decided to go to the winery to try to stop the truck, set on physically blocking its path if needed. Soon, the rest of Marsala — even the mayor — arrived to join the resident to resist the ship’s removal.

“Everyone came,” Alagna says. “It was too important not to.”

It was a “day of DRAMA, hardly less than that of ship’s sinking,“ Frost wrote in her journal that night.

After hours of blocking the road with their bodies, the people of Marsala claimed victory. A decision was reached to convert a nearby abandoned winery, called the Baglio Anselmi, into a museum to display the ship.

~~

Alagna still shows up to work every day at his family’s winery. A framed photo of Frost and an illustration of the Punic ship in battle hang on the wall of his spacious office. In the Cantine Pellegrino’s large, cool tasting room, perfect plaster replicas of several of the ship’s pieces are mounted on display.

Frost continued diving until a few months before her death in 2010, at the age of 92. By then, she had helped survey the Pharos lighthouse of Alexandria, Egypt, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World; she had excavated at the UNESCO World Heritage site in Byblos, Lebanon, believed to be one of the oldest cities in the world; and she had co-founded journals and institutions devoted to underwater archaeology.

Her Punic ship findings remain her greatest academic achievement.

According to instructions in her will, proceeds from an auction of her estate established the Honor Frost Foundation, which carries on her legacy of underwater archaeology in the Mediterranean. Her ashes were scattered off the coast of Lebanon — perhaps someday to be swept along the same ancient trade routes that once brought the Punic ship to Marsala.

Finally at rest, the Punic ship today holds court in a wing of its own at the Baglio Anselmi Regional Archaeological Museum, at the point of Marsala’s Boeo cape. Sculptures, amphorae, and other Roman and Phoenician artifacts line the onetime winery’s cavernous halls. The ship’s remaining pieces are fitted into a large iron frame to give visitors a sense of the scale and lines of the original 115-foot ship. A raised platform allows examination of the ship’s joints and clay amphora resting in the hull. The Phoenician letters are no longer visible, their water-based pigment having faded in the light. But thanks to Frost’s careful cataloguing and publication, the shipbuilding secrets live on.

Through it all, the mercurial waters of the Mediterranean churn as they always have, providing refuge as well as peril to untold ancient treasures.

On the western coast of Sicily, Marsala overlooks the Mediterranean Sea on the ancient site of the Carthaginian settlement of Lilybaeum. The city’s modern name means “Harbour of Allah” in Arabic. Photo: Giacomo Gabriele.

Janna Brancolini

Janna Brancolini is an American journalist based in Milan, Italy. She is drawn to stories where law meets politics, where the environment intersects with finance, where cultures clash, and where languages collide.