Support Hidden Compass

We stand for journalism, science, history, and hope. Make a contribution to Hidden Compass and stand with us.

A couple of years ago, looking through all the souvenirs and memorabilia that have accumulated in my flat over decades of travel, it occurred to me that objects are symbols: We collect them, and cling to them, primarily for the stories they embody.

My work-in-progress is a book called 108 Beloved Objects. I’m not only eliciting stories from my keepsakes, but I am also giving each object away. This book is a way of breaking my attachment to the physical world — because once we have internalized an object’s story, why do we need the object itself?

Why 108 objects? This number is deeply significant in Eastern spiritual practice, and beyond. It is the number of prayer beads on a Buddhist rosary, the number of yoga postures in a full cycle, and the number of stitches on a baseball.

Here are stories about two of the objects in the collection:

Prankster

Painting by Mary-Ellen Thomas.

Varanasi was a City of Liars: a place as oily and opaque as the river Ganges, which — flowing steadily between high stone temples — has for centuries been India’s most revered site for cremation rites. During my visit to this Indian city in 1985, I was lied to about everything: my fare from the train station, the price of my lunch, the cost of a handkerchief.

After rowing me onto the Ganges at dusk, my boatman announced that he would overturn our flimsy vessel, dumping me and my camera into the corpse-laden river, if I didn’t double his already exorbitant fee. To underscore his threat he pulled in the oars and rocked the boat violently from side to side.

I told him that I didn’t have the money on me, that I never carried that much cash at one time. But my hotel was right by the riverside. He could come to my room to collect it if he returned me safely to shore.

Gamely he rowed me back. The moment the keel touched the dock I leaped out and began running, knees high. He followed in pursuit, shouting, chasing me down the street with an oar.

I finally lost him in the Night Market, a maze of bulb-lit stalls packed with cotton sellers and goldsmiths, mangos and chess sets, woven silk brocades snapping open like iridescent fireworks. I rounded a bend and ducked into a shop selling small devotional statues. The shiny brass gods and goddesses came with accessories: a crown for Ganesha, a skirt for Kali, a bow for noble Laxman.

One of the statues caught my eye. It was Krishna: lover, prankster, and slayer of river demons. I paid a high price for the figure and his add-on flute — which, despite the merchant’s assurance, is not really silver.

Protector

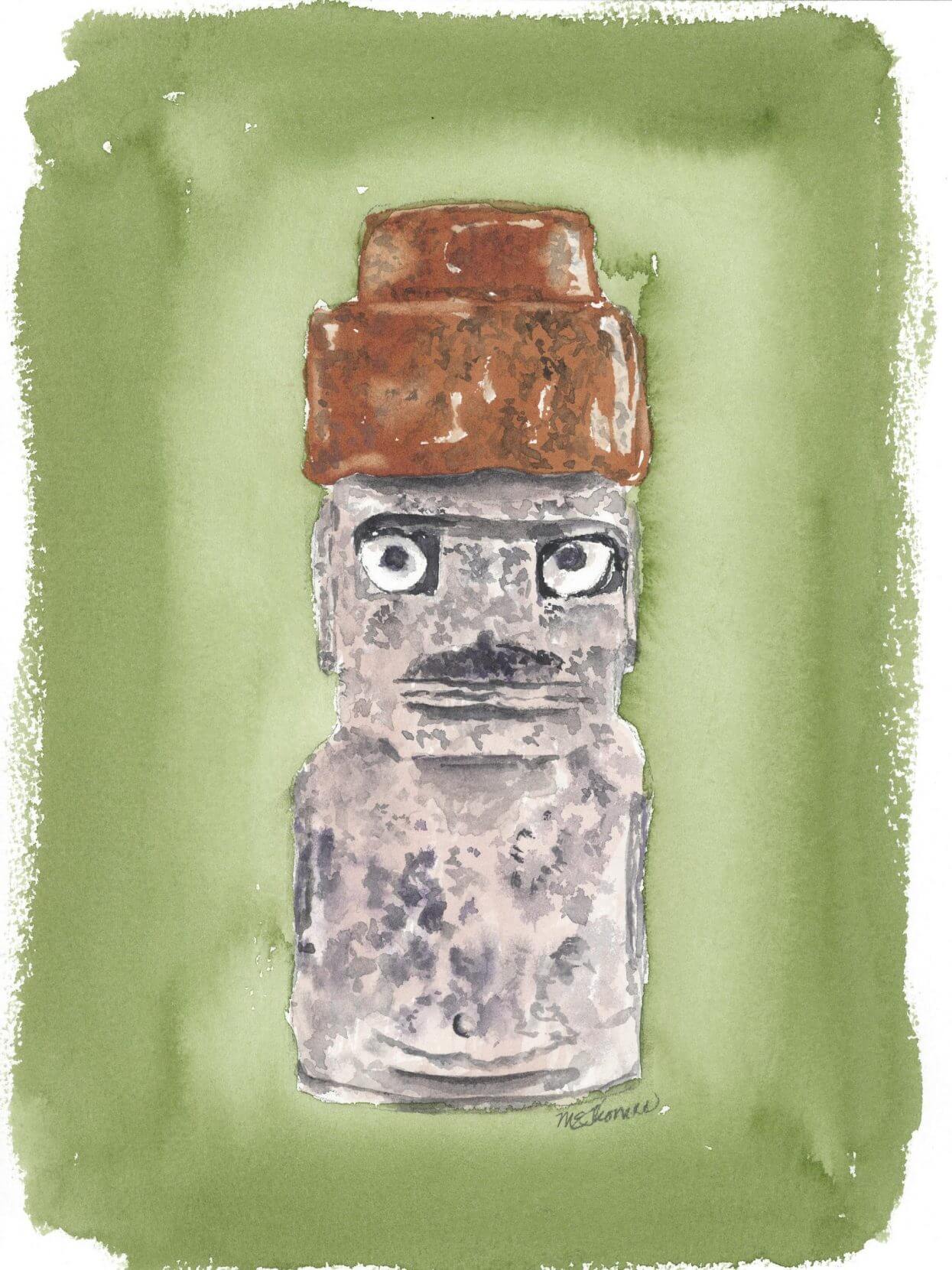

Painting by Mary-Ellen Thomas.

The closer one gets to this isolated landfall, 2,290 miles off the coast of Chile, the faster its name changes — like one of the elusive destinations in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities.

What I knew from textbooks as Easter Island (a Portuguese explorer first made landfall on Easter, 1722) became Isla de Pasqua on my boarding pass from Santiago. On arriving, I learned I was actually on Rapa Nui: The Big Island. And as I moved deeper into the landscape, across grassy hills punctuated by fallen and restored moai, I heard a quieter name: Te Pito O Te Henua, The Navel of the World.

There are 887 imposing moai in all, carved from volcanic tuff (the eyes are coral and obsidian). Most tower about 14’ high. Legend claims some literally walked to their final locations using mana: spiritual power. Though they look stern, they were not meant to threaten. These were protector deities. Erected in rows along the rocky coastline they face not the ocean but inland, watching over their tribes.

Their purpose, dates of creation, and actual method of transport are vague. History on Rapa Nui is a pliant commodity. Stories are relayed within families, between families, to archeologists and journalists, guidebook authors, and crackpots. No one knows anything for sure. This is not a problem. To the contrary: it’s as if all possible stories are true.

The leader of my press trip to Rapa Nui was a lithe, perceptive, and hilarious German woman named Anna. We’d traveled together before, and I was hopelessly in love with her. I wanted nothing more than to be her moai; to watch over her through the centuries, keeping the elements at bay. Alas, she was engaged to another man. Still, we spent many hours together on that remote island. One day, after shopping for souvenirs, we visited the post office, where the amused clerk stamped our passports with Easter Island postmarks. Those, my journals, and the miniature moai Anna helped me choose are all I will ever need to recall the mysteries of Rapa Nui, and my mad infatuation.

At a certain point in our lives, the moai within us start to pivot, turning from the tempest and toward the slower-moving rhythms of our inner landscape. It’s all right. I’m not there yet, but the mana is rising. Because no matter which way I face, nothing is fully lost. I can still hear the waves, the thwop of rubber stamps on paper, the laughter rising from the alternate world that Anna and I might have inhabited.

###

Mary-Ellen Thomas is a self-taught artist from Georgetown, TX. Working primarily in Watercolor, her work has been featured in shows at Texas State University and Grace Heritage Center. Her paintings hang in restaurants in the Central Texas area. Her art supports the non-profits Homes for Heroes, the Veterans Field of Honor and the Delta Kappa Tau Society’s scholarship fund. She is a member of the Texas Watercolor Society.

Jeff Greenwald

Oakland-based Jeff Greenwald remains either the world's most obscure well-known travel writer, or the best-known obscure travel writer.

Never miss a story

Subscribe for new issue alerts.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive updates from Hidden Compass regarding new issues and other ongoing promotions such as workshop opportunities. Please refer to our Privacy Policy for more information.