Support Hidden Compass

We stand for journalism, science, history, and hope. Make a contribution to Hidden Compass and stand with us.

“Pablo! Get back in the closet!” I yell over gunfire.

Unarmed and unaware of the encroaching danger outside, Pablo Escobar retreats to the bathroom closet with a startled backward leap. I kneel low under the panorama window; chips of blue shower tiles dig at my knees.

Years ago, this oversized window must have given Escobar a tranquil view of Lake Guatapé. Hidden in his island fortress, away from the street violence of Medellín, Colombia’s most successful and ruthless cocaine kingpin thought he could let his guard down. He might have gazed out the window while he brushed his teeth or laid under a mountainous bubble bath, but now, it’s a tricky place to defend. In the chaos of the moment, I haven’t the time or the inclination to consider how I’ll defend my part in this to my own conscience when it’s over.

From the garden below, I hear the South Africans strategizing in Afrikaans. They haven’t spotted me. Yet.

As much as I want to go down with my drug lord, for the sake of honor, I don’t want to get shot at close range.

I pop up and fire in what I think is their general direction. I’ve learned to never shoot from the same place twice, so I crawl to the front corner of the window as they return fire, which strikes the wall behind me with a series of successive thumps.

I wait for a lull and shoot again. The South Africans’ blue Seguridad jumpsuits don’t do much to camouflage them against the concrete walls. My red Medellín Cartel suit is even worse.

“They’re under us! Guard the stairs,” warns one of my comrades.

“I don’t have any bullets!” Pablo cries from the closet.

Hearing the cacophony of the firefight on the first floor coming closer, I know I have only a few seconds to make my next move. I could take cover at the end of the stairs and attack the South Africans as they’re bottlenecked on the steps, single-handedly eliminating them all. But it’s risky. As much as I want to go down with my drug lord, for the sake of honor, I don’t want to get shot at close range. Two blue jumpsuits rush up the stairs and, as if it were a reflex, I raise my gun in the air.

Surrender. I’ve left Pablo unguarded.

I’m at the back door — hands and gun raised high — when I hear the sting of high-powered paintballs breaking flesh at close range. It’s all over when our designated Pablo Escobar — a red-bearded, chubby Irish boy — screams, “Ok, ok! I’m dead!”

Pablo Escobar’s island fortress overlooking Lake Guatapé shielded him from the chaos that his cocaine cartel created on the streets of Medellín, Colombia. PHOTO: THOMAS PEDDLE.

~~

The real Pablo Escobar was killed not in his lake house, but in a residential neighborhood of Medellín on December 2, 1993 — probably around the time when our pretend Pablo was born. Who exactly killed him, or who or what they represented, is difficult to say. Officially, Search Bloc, a Colombian task force, fired the shots, but the group used American intelligence and was probably bankrolled by the American government. Certain members of Search Bloc, and perhaps their American CIA advisors, might have also been collaborating with Los Pepes or “the People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar.” And while Los Pepes presented itself as a grassroots effort to end the constant violence that Escobar brought to Medellín, the group was organized by Escobar’s greatest drug-trade rivals, the Cali Cartel. There were not, however, any 20-ish, beefy South African bros involved in Escobar’s death. At least, no South African bros appeared in the Netflix series Narcos, which is where I learned all of my Escobar knowledge before traveling to Colombia.

Released in summer 2015, Narcos is part of the continuing public fascination with Escobar —at this point, he’s his own niche genre. Want to know about Escobar as a father? Read Pablo Escobar: My Father (2016). As a brother? Try My Brother – Pablo Escobar (2016). In relation to the failed War on Drugs? Pablo Escobar: Beyond Narcos (2016). As an example of the corrupt dealings of the CIA? Killing Pablo: The Hunt for the World’s Greatest Outlaw (2001). If you’re more of a movie person, no worries! Javier Bardem and Penelope Cruz recently starred in a Spanish-language film titled Loving Pablo, based on the memoir Loving Pablo, Hating Escobar (2017).

The appeal isn’t hard to understand. The third son of a poor farmer, Escobar made his way onto Forbes’ list of international billionaires by breaking rules that didn’t suit him. And despite his violence and mayhem, he loved his wife and his children. He was a model gangster.

With all of his posthumous, not-so-negative publicity, it can be difficult to remember that Escobar wasn’t a good guy forced into a bad situation, or a modern Robin Hood: he was a narco-terrorist. One of the highlights of his rap sheet was organizing the bombing of a domestic flight between Bogotá and Cali in an attempt to assassinate a presidential candidate, killing 107 people. To avoid extradition to the United States, he paid a left-wing guerrilla army to attack and hold the Colombian Supreme Court hostage. It’s estimated that between the late 1980s and his death in 1993, Escobar ordered more than 5,000 killings. Hitmen on his payroll roamed the streets of Medellín, battling politicians and police officers and anyone else who refused to be bribed or dared to challenge Escobar’s power. According to the Spanish newspaper EL PAÍS, more than 100 bombs exploded in the city between September 1991 and December of that same year. The culture of violence created by Escobar so permeated Medellín that it became known as “The Murder Capital of the World.”

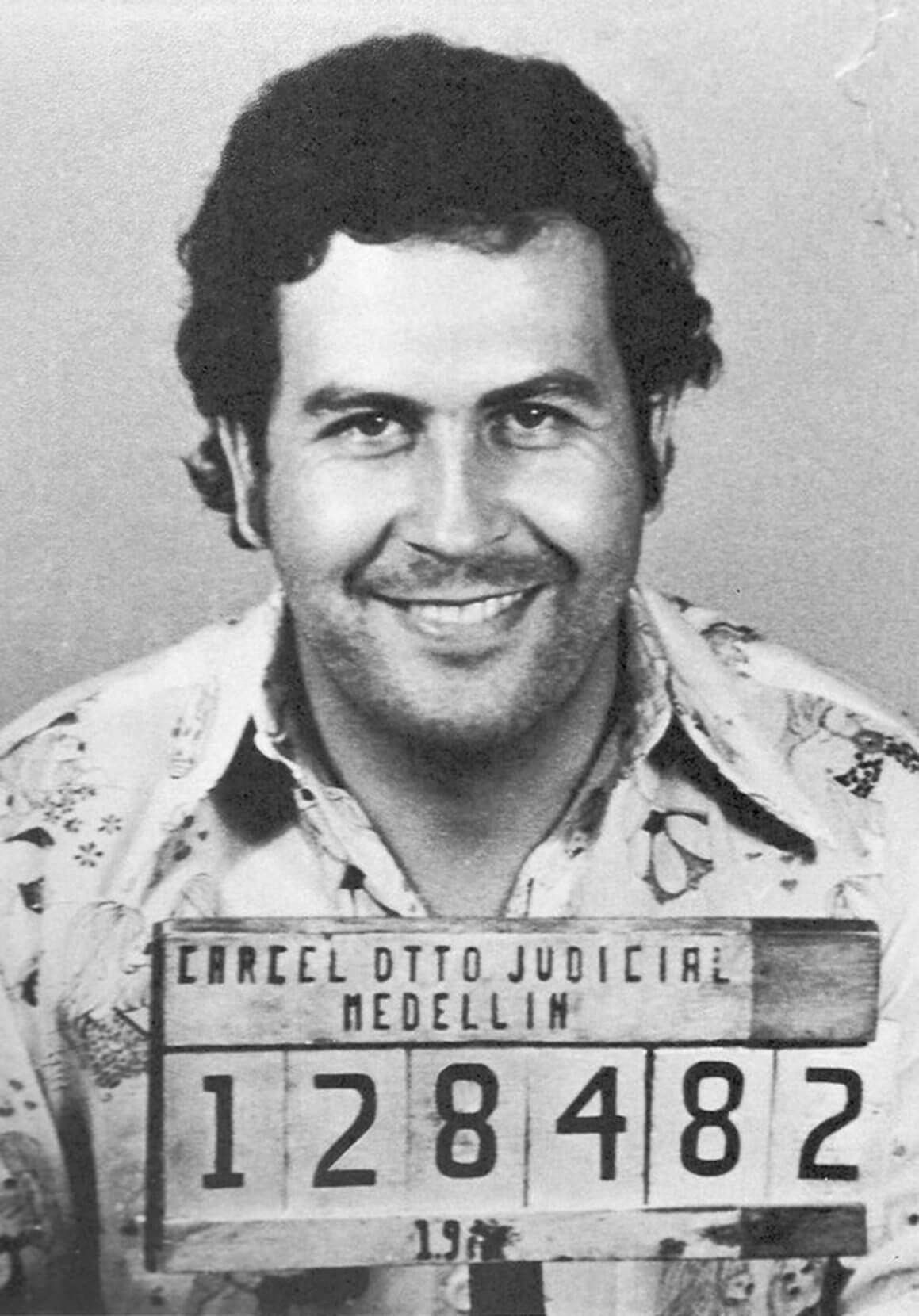

In 1977, Pablo Escobar, also known as Don Pablo and El Zar de la Cocaína, was emerging as one of the richest men in the world, propelled by the popularity of cocaine in Miami and New York clubs.

But as Colombia, and Medellín in particular, emerge from the aftermath of the bloody 1990s, Escobar is becoming a tourist draw. Pablo-themed tours of Medellín offer travelers the chance to see his church, the Monaco Building where his feud with the Cali Cartel began, the building where he was killed, and his grave — all in an air-conditioned minivan. For an additional fee, you can visit La Catedral where Escobar briefly jailed himself to avoid a U.S. prison sentence. The local government recently shut down a museum dedicated to the man and supported by his family, for permitting reasons. Further north, in Santa Marta, the Dropbear Hostel flaunts its past as a cartel safe house (where Pablo might have stayed) with tours every Tuesday and Thursday and rumors of gold and cocaine hidden in the hostel’s walls. His former Hacienda Napoles, outside of Bogotá (home to his famous herd of feral, sex-crazed hippos) is on its way to becoming a safari park. And then, in Guatapé, there are four rounds of high-powered paintball on Escobar’s private island.

~~

The course stretches behind a swampy green swimming pool through Escobar’s family villa, across a garden, and inside horse stables. Teams take turns defending a designated Pablo in his house from attacking Seguridad (or Cali Cartel if you prefer) forces outside. Only shots to the torso or head count as kills.

“Keep your mask on,” we’re warned in the gun room, “a girl took a paintball to the eye earlier in the month.”

Do thoughtful, culturally sensitive travelers play cops and robbers at a real murderer’s house — a place where the decision to kill had ended in real bloodshed?

After the warning, I turn to my friend. “I can’t believe we’re here!” I squeal.

For months, I’d been telling people I was going to Colombia to play paintball at Pablo Escobar’s house, and finally, I was standing in the gun room. Of course, the game wasn’t the sole reason for the trip, but it sounded the best. I’d become giddy when casual conversations started to turn towards summer plans, anticipating the looks on friends’ faces and their reactions when I told them. I especially liked adding that the trip came with a free breakfast burrito.

A shirtless teenage boy is robotically dumping a measuring cup of fluorescent orange faux-bullets into my gun when I discover that my assigned jumpsuit is already sweat-soaked. Cringing, but not deterred, I grab the damp suit, take the loaded weapon, and pass the boy as I head onto the villa’s lawn. In seconds, the sweat is mostly mine.

While the teams pick Pablos, I gaze into the abandoned house. I don’t think of Escobar’s children playing on the porch or the thousands of children left without fathers on his orders. I don’t contemplate the opinions of the shirtless boy, who watches backpackers stream past him every day to replay one of his country’s darkest chapters. My concerns are those of strategy — run to the top floor or hold out on the bottom?

~~

Many months later, after I’d told and retold the story of the vicious South Africans and abandoning pretend Pablo in the bathroom closet, I started to wonder — for no particular reason — if I was an asshole? Did I behave like one of those terrible backpackers who use developing countries as adult playgrounds? Do thoughtful, culturally sensitive travelers play cops and robbers at a real murderer’s house — a place where the decision to kill had ended in real bloodshed? Once I began to think about it, I couldn’t stop.

The paintball game wasn’t make-believe the way children invent imaginary heroes and villains: it was a version of a violent truth. A real Pablo Escobar had existed and lived in that house and murdered with real guns. Only a generation later, those details were blurred so that I could take home a funny story, like a souvenir shot glass. No one expected me to learn about the real carnage.

But what if it hadn’t been a game when I raised my arms in surrender? What if I wasn’t afraid of bruises, but of bullets and bombs? What if all of us, the South Africans, my teammates, and I, were actually among the thousands who fought for our lives — and lost?

Backpackers get an adrenaline surge by shooting paintball rounds with make-believe Escobars at the cocaine kingpin’s former villa, but many of the locals are unamused. PHOTO: THOMAS PEDDLE.

Victoria Sanderson

Victoria Sanderson is a restless writer always googling new adventures.

Never miss a story

Subscribe for new issue alerts.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive updates from Hidden Compass regarding new issues and other ongoing promotions such as workshop opportunities. Please refer to our Privacy Policy for more information.