Support Hidden Compass

We stand for journalism, science, history, and hope. Make a contribution to Hidden Compass and stand with us.

With his left leg lifted and held across his body at the hip, Punnainallur Nataraja balances gracefully. He stands exuberant — ringed by flames, locks of hair swaying toward the cosmos. He is Siva, the Hindu god of supreme divinity, incarnated as the Lord of Dance.

A vision in bronze, likely created in the 10th century, this particular sculpture also represents the artistic mastery of the Chola empire, one of the world’s longest-ruling dynasties, a reign that lasted for more than 1,000 years and stretched from southern India to Indonesia, Myanmar, and beyond.

For decades, the refined statue held that pose in a museum gallery in New York, part of a prized collection of Asian artifacts.

But possession is a multifaceted word, particularly when it comes to Hindu idols. And this Nataraja, like countless other bronzes created over the centuries, did not come into this world to stay immobile.

~~

A faint shaft of light shines on the rough contours of a small, wax object held in the hands of a man seated cross-legged on a low stool. Hunched over a bench and immersed in the task at hand, he takes a chisel to the form, his white sarong-like veshti and crisp cream-colored khadi shirt gleaming in the sun, which pours through the grille roof above him.

Strewn around the square courtyard are many more idols of Hindu gods and goddesses. They stand from a couple of feet tall to nearly my height — some finished, others in different stages of production.

Burning incense sweetens the air. Clinks and clangs provide a steady soundtrack. The faint melody of a popular Tamil song drifts in from the wide, tin-roofed backyard.

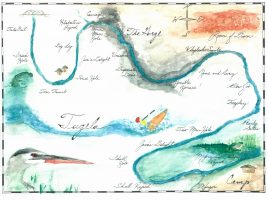

Here, in the remote village of Swamimalai in the Tamil Nadu state of southern India, the journey begins for Chola bronzes the same as it has, day after day, for more than a millennium.

Chola bronzes are sacred idols, also known as panchaloha idols, that beat at the heart of Tamil culture. But my feeling of ownership for this particular tradition runs deeper: My family counts among the devotees that travel far distances to come to the luxuriant hamlet of Swamimalai to pay obeisance to Lord Swaminatha Swamy, a six-foot, black granite idol presiding from a small hillock with his divine weapon, a spear, in his right hand.

When I look at a Chola bronze, whether an exquisite Nataraja or other depiction, I don’t see a prize showpiece to display as decoration. These idols form an integral part of my culture’s sacred realm, brought to life through ritual.

In an array of bronze foundries below, panchaloha idols continue to be cast by hand. In all my visits to my family’s ancestral village, I had never before stepped foot in this foundry, nor learned the intricacies of the “lost wax” technique used to cast each of these enigmatic idols here.

But a stunning shift in the world of looted antiquities had seized my curiosity.

~~

As I sipped my fourth cup of filter kaapi, lazing on the couch amid India’s seemingly endless COVID lockdown, I flipped on the TV and landed on a Tamil news channel. What I saw on the screen nearly made me spit out my coffee: British authorities handing over a triad of bronze idols to their Indian counterparts.

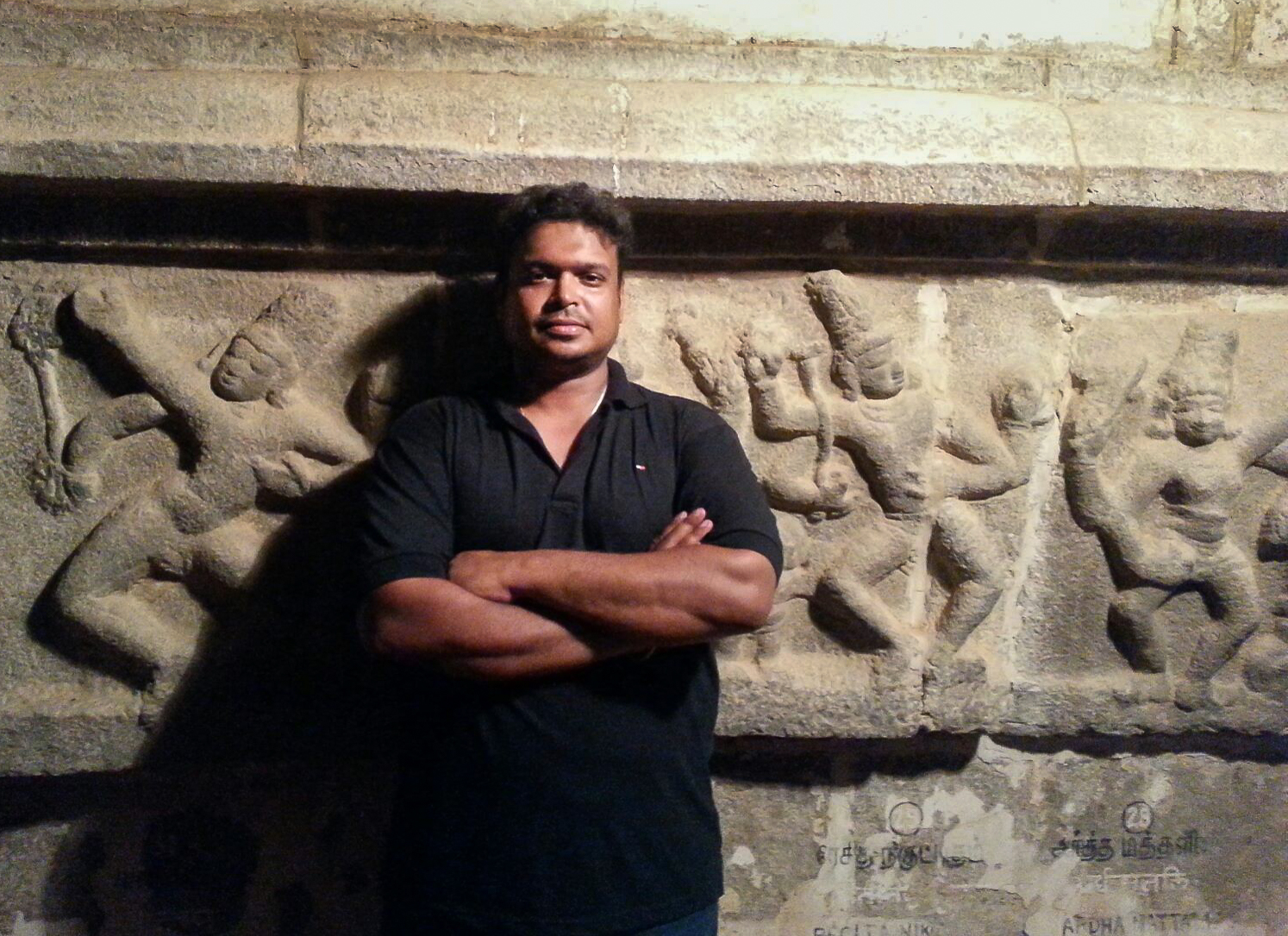

A man in a blue-checkered formal shirt appeared on the program. His name, S. Vijay Kumar, was a name I had come to know well. The glint of pride in his eyes was impossible to miss as he talked about these pieces of India’s lost heritage making their way home. As a volunteer art sleuth, he had played an integral role in that process.

S. Vijay Kumar helps track down cultural artifacts stolen from India. Photo: Courtesy S. Vijay Kumar.

Where Kumar was poised and composed, I was rejoicing in my living room about this surreal turn of events. I felt as relieved as if they were my own precious heirlooms.

When the news anchor credited him for the artifacts’ return, however, Kumar pursed his lips. After a pause, he responded in a baritone voice, “It’s teamwork.”

In that moment, I knew I needed to thank this defender of heritage myself. I also wanted to learn his secrets.

~~

A couple of months after watching him on TV, I spoke with Kumar on the telephone. Over the past few years, social media had introduced me to his work — the shipping executive turned stolen artifact vigilante. We are both members of several online heritage groups dedicated to temples, sculptures, and architecture.

Yet this was my first conversation with him. I was hoping for a detailed explanation of how he tracks down panchaloha idols and other Indian artifacts.

A stunning shift in the world of looted antiquities had seized my curiosity.

“It’s years of persistence,” he said, with the same poise he exhibited on TV. But his soft demeanor wasn’t all modesty. As I pushed for details, I could sense an air of secrecy shrouding his responses.

Still, his passion for Indian heritage was clear. A native of Tamil Nadu, he had started out as “just another tourist at historical sites,” he told me, blogging about the nuances of Indian art. As he became more knowledgeable about iconography and history, though, he and his fellow heritage enthusiasts, aided by Indian scholars and researchers, began to update outdated archaeological records with high-resolution photographs.

Along the way, they noticed something startling.

Many artworks, often bronze idols, had vanished. Not only were temples missing their artifacts, but even India’s records and repositories had gaping omissions. Police investigations had been closed, with thefts deemed untraceable. In other, perhaps more troubling instances, fake artifacts had replaced stolen items and evaded detection.

That’s when Kumar and his team recognized their help and expertise might be put to service. What was once a group of bloggers and documentarians transformed into a team of online detectives.

But even they couldn’t have predicted the magnitude of the problem.

~~

As captivating as I found Kumar’s tale of artifact hunting, there was something else he had said during the TV interview that resonated with me on a deep level.

“The gods want to come home,” Kumar had told the news anchor.

When I look at a Chola bronze, whether an exquisite Nataraja or other depiction, I don’t see a prize showpiece to display as decoration. These idols form an integral part of my culture’s sacred realm, brought to life through ritual.

They also offer a window into the Chola heyday, when artisans began casting these portable idols, known as utsava murtis, in bronze. After communing with the faithful during religious processions — sometimes along roads lined with banana trees planted in honor of the idols — the sacred statues returned to their temples.

But safe in their sanctum sanctorum they were not.

~~

During early invasions of southern India, Chola idols were sometimes thrown into wells, or stacked away in the backyards of temples in an attempt to protect them from being carried away as a sign of conquest.

Today, Chola bronzes fetch millions on both the black and open markets for antiquities.

A UNESCO estimate from 1989 suggested more than 50,000 idols and antiquities had been smuggled from India. Kumar estimates that at least a thousand artworks are stolen each year.

“Before, it was the invaders, but now it is our own playing mischief,” Kumar told me with a sigh. On the black market, these smuggled artifacts often find their way to esteemed galleries in the West. In those settings, the objects are proudly flaunted as prized possessions.

A bronze Nataraja sculpture resides at the Art Institute of Chicago. An artifact from India’s Chola empire, this idol was sold to the museum in 1965 by William H. Wolff, a now-deceased New York art dealer who admitted to sometimes practicing questionable tactics in the export of antiquities. Photo: Cathyrose Melloan/Alamy.

That’s where Kumar and his team come in: They meticulously comb museum collections, both online and in person, and keep a close eye on art auctions, art dealers’ websites, and private sales. Collaborating by private emails and secure calls, they use their expertise and understanding of period materials, styles, and regional differences to compare and identify matches using high-resolution photographs. They also work closely with international agencies including Interpol and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

At this point in our conversation, Kumar’s voice became more guarded. His team, now a group of a dozen or so core members and more than 250 volunteers around the globe, had always wished to remain a faceless crowd of detectives. It’s a matter of personal safety: Getting in the way of the illicit art trade can provoke death threats.

But a major breakthrough a decade ago compelled Kumar to surrender his anonymity.

~~

On a spring evening in 2009, a well-heeled crowd of Manhattanites gathered at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. As The New York Times tells it, they ate spring rolls and sipped white wine as the man of the hour, a 60-year-old art dealer with a receding hairline and rimless spectacles named Subhash Kapoor, mingled convivially. The group of 30 or so had come together to celebrate Kapoor’s recent gift of 58 drawings from India, his country of origin, to the New York museum.

Two years later, Kapoor presented his passport at the airport in Frankfurt, Germany — only to be swarmed by Interpol officials and arrested.

This dramatic reversal of fortunes marked the culmination of a multiyear investigation, codenamed Operation Hidden Idol by U.S. authorities. The charge: Kapoor had achieved prominence — and built his fortune — on looted artworks and antiquities. He and seven conspirators were accused of running a smuggling ring valued at an astonishing $145 million.

Over the prior 30 years, the art dealer had risen through the Manhattan art world to run an esteemed gallery, Art of the Past, on Madison Avenue. His Hindu, Buddhist, and South Asian antiquities sold for seven figures — and higher — to prominent curators and collectors around the world, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art to the National Gallery in Australia.

On the black market, these smuggled artifacts often find their way to esteemed galleries in the West. In those settings, the objects are proudly flaunted as prized possessions.

At the same time, investigators allege, Kapoor had built a smuggling network.

Under the cover of night, his crew had looted remote temples in India, Pakistan, Nepal, Cambodia, and elsewhere, sometimes during archaeological excavations. They would load antiquities — thousands of them in total — into trucks and ship them around the world. Upon arrival in developed countries, these idols would be restored, as needed, and sold with falsified documents of provenance — Kapoor’s specialty.

The arrest of Kapoor and the seizure of the stolen goods that filled his storerooms marked a turning point in the struggle to repatriate Indian heritage. For one thing, it forced prominent museums to reexamine their connections to Kapoor.

It also compelled Kumar, who had collaborated with Interpol on the case, to step out of the shadows to help lead the battle.

As Kumar writes in his book, The Idol Thief, “[Kapoor’s] arrest caused an earthquake in the art world, the tremors of which are still being felt.”

~~

As my phone conversation with Kumar neared its end, he echoed a sentiment popular among many Indians — that the artifacts he has helped return are just a handful of the many thousands of antiquities stolen and tucked away in foreign museums and private collections.

That’s why Kumar and a friend, Anuraag Saxena, formalized and went public with the India Pride Project in 2013. In the years since, they have become a beacon of hope for villages and temples across India that have been stripped of their sacred, ancient treasures — treasures like a 10th century bronze Nataraja statue missing from the Tamil Nadu village of Punnainallur since 1971.

The way the India Pride Project takes heritage into their own hands inspired me, at long last, to return to Swamimalai and its foundries. I wanted to do more than feel ownership of the artistry behind each panchaloha bronze; I wanted to become immersed in the alchemy.

~~

“Vanakkam. Please sit here. My brother will attend to you soon,” said D. Srikanda Sthapathy, a short bespectacled man in a white veshti, as he welcomed me to the courtyard of their foundry. His brother, D. Radhakrishna, continued to concentrate intently on the object in his hand.

Here, in the remote village of Swamimalai in the Tamil Nadu state of southern India, the journey begins for Chola bronzes the same as it has, day after day, for more than a millennium.

I sat on the floor, barefoot, glad for respite from the simmering heat of the midday. As is tradition, I had removed my shoes upon entry. My gaze returned to the idol on the bench: I could make out a trunk and huge belly. Even in the sunlight, though, the object didn’t glitter — a fact that perplexed me. Had I come to the right place?

Srikanda noticed the puzzled look on my face. “The wax model is the first stage of making a panchaloha idol,” he explained.

Srikanda returned to a statue with a chisel and hammer. Six other artisans, deep in work, sat on the floor by his side. As he worked, he proudly told me about his craft.

Working on the floor of a heritage foundry in Swamimalai, craftsmen cast panchaloha idols by hand and carry on the “lost wax” tradition mastered during the Chola empire. Photo: Meenakshi J.

There are other bronze workshops in Swamimalai, but this foundry claims a documented genealogy that traces back at least 10 generations of panchaloha sculptors. The brothers’ ancestors, I am told, settled here during the Chola empire. Even as the foundries in Swamimalai continue casting panchaloha idols, the number of remaining sculptors dwindle with each generation.

“We only accept orders from temples and religious centers, and rarely from private art collectors,” Srikanda added. Their handcrafted and sacred designs, he explained, are based on the Shilpa Shastra, an ancient treatise on arts and crafts that outlines distinct specifications for sculpture and Hindu iconography.

Burning incense sweetens the air. Clinks and clangs provide a steady soundtrack. The faint melody of a popular Tamil song drifts in from the wide, tin-roofed backyard.

Precise measurements appear in Shilpa Shastra in the form of a dhyana slokam — a hymn. Other details, such as the size of the crown and platform, are left up to each sculptor.

Srikanda paused. “To explain to you the intricacies of these might take up a whole year,” he said, chuckling. “One cannot learn all these shastras in a crash course.”

I nodded and smiled, eager for him to go on. I knew that somewhere in those details was what saves these idols.

~~

Radhakrishna Sthapathy, who looked perennially to be in a Zen state, again sat cross-legged in front of me. He closed his eyes and recited a hymn, then started another wax model. Soon, he deftly used his fingers to shape a sample figurine out of a pliable mixture of beeswax and resin, gauging the measurements with a coconut leaf strand.

“We follow the same procedure as that of our ancestors,” Srikanda said, as I looked on, entranced. Even the incessant clinks and clangs took on a meditative quality.

The portable mini-furnace beside him burned bright, as another artisan stoked a fire. His job was to give the wax model further detailing, then pass it on to another sculptor, who designed a clay mold out of a combination of vandal mun — an alluvial soil from the banks of the River Kaveri — and sand, to encase and dry the figurine in the sun for a week.

The pack would then be baked surrounded by dried cow-dung patties and firewood in an earthen oven until the wax melted and ran out through drainage holes.

I knew that somewhere in those details was what saves these idols.

Left inside would be detailed crevices, a now waxless mold known as karuvu, or womb, in Tamil. This mold would, at last, be ready for casting. Srikanda explained that this next stage only takes place on a moonless night, or on an auspicious day according to the Hindu almanac.

I thought back to the elephant figure I had spotted upon my arrival at the foundry. It was a wax model of Ganapathi, the Hindu god of new ventures. What an auspicious beginning to my trip to the foundry, I noted to myself at the time.

Now, I could see the truth in that thought: Witnessing the casting would open up new layers of understanding about this heritage I hold dear.

As it turned out, the secret to a Chola bronze’s singularity was one and the same as its salvation.

~~

Several months earlier, I asked Kumar about something I had wondered for many years. Why are panchaloha idols so often the target of looting — and even more than that, how are the thefts detected with such confidence?

He had paused for a moment and laughed, perhaps owing to my ignorance.

“It’s not just the panchaloha idols that are often stolen, and neither is it easy to identify them,” Kumar clarified. But what sets the panchaloha idols apart, he said, is as much a part of their allure as of their thieves’ undoing.

“Their unique design, combination of metals, and almost thorough documentation,” he explained, “have helped the Chola bronzes to be tracked down.”

In the foundry, as Srikanda demonstrated how the idols are cast, I watched the empty mold get heated and then buried in the ground, up to its mouth or opening, before molten metal was poured in, filling the crevices of the panchaloha.

An amalgam of copper, brass, lead, gold, and silver varies in proportions, based on the trace amounts of gold and silver requested by the client. Otherwise, the percentage of the first three ingredients more or less remains near 82%, 15%, and 3% respectively.

So integral is this blend that it’s right there in the name: Panchaloha translates to “five metals” in Sanskrit.

Witnessing the casting would open up new layers of understanding about this heritage I hold dear.

After the mold gradually cools, Srikanda explained, it is broken and discarded, never to be used again. This uniqueness, both in mold and in metal composition, makes the statues irresistible to smugglers — and, as Kumar had mentioned, can also aid in their identification.

Using hand tools, a sculptor in Swamimalai meticulously refines the details of a bronze figurine. Photo: Meenakshi J.

The resulting raw figurine is chiseled, filed, and engraved according to scripture. In the last stage — jedi bandhanam — the figurine is attached to a metal platform and polished to perfection in able hands.

But even with its precise metallurgy, panchaloha idols do not belong in the realm of objects.

~~

Two months after my visit to Swamimalai, I watch another news update, this time on the Indian Prime Minister’s visit to the United States. Again, I watched in awe as more of the Kapoor loot was handed over — a haul of 157 stolen artifacts being returned by the Biden administration.

A month later, the U.S. would return an additional 91 artifacts to India. Of the 248 total pieces, all but 13 had been smuggled into the U.S. by Kapoor, who has been charged with 86 criminal counts and is awaiting trial. To news sources, Kumar called it “the single largest restitution of stolen antiquities to India.”

My astonishment was not a matter of hyperbole. At the time of Kapoor’s 2011 arrest, fewer than 20 antiquities had been returned to India from foreign countries since 1972.

Thanks, in part, to Kumar and his global group of heritage enthusiasts and online sleuths, the tide has turned. More than 1,000 other stolen Indian antiquities are reportedly in the process of being retrieved from around the world, including from the United States, Australia, Singapore, Germany, Canada, and England. Kumar told the Times of India that the India Pride Project has their sights on an additional 700 antiquities in the coming year alone.

At the time of Kapoor’s 2011 arrest, fewer than 20 antiquities had been returned to India from foreign countries since 1972.

Prominent among the haul from the U.S. is the 10th century Nataraja that went missing from the Punnainallur village temple in Thanjavur in 1971.

Indian officials had long ago closed the case and replaced the figure, calling the stolen idol untraceable. Through a confidential tip, though, the India Pride Project managed to track the Chola bronze to New York’s well-respected Asia Society Museum.

~~

In centuries past, when a Chola bronze set out from the temple, the sounds of drums and conch shells resounded while devotees chanted and danced in torch light. On a regal palanquin shouldered by temple workers, the bronze deity would stand, draped in silk finery and ornamented with flowers and rubies, diamonds, pearls. Only the face, sometimes just the eyes, remained visible. Bystanders waved off insects with wispy fans made of the hair of yak tails.

After communing with the faithful during religious processions — sometimes along roads lined with banana trees planted in honor of the idols — the sacred statues returned to their temples.

In 2019, a different bronze Nataraja returned from the Art Gallery of South Australia in Adelaide to similar fanfare. Removed from its sealed box and draped in a silk vest and floral garlands, the 16th century idol arrived at a train station in Chennai, where a crowd sang Tamil hymns in celebration. From there, it continued its procession, by police escort, to the Kallidaikurichi temple from where it had been stolen in 1982.

India’s bronze gods are once again on the move. But finally, they’re coming home.

A Chola bronze depicting Nataraja greets the faithful at a Hindu temple in Madurai, the cultural capital of India’s Tamil Nadu. Photo: Dinodia Photos/Alamy.

Meenakshi J

Meenakshi J is an India-based freelance writer who finds solace in wholesome vegetarian food, instrumental music, historical ruins, and ancient art.

Never miss a story

Subscribe for new issue alerts.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive updates from Hidden Compass regarding new issues and other ongoing promotions such as workshop opportunities. Please refer to our Privacy Policy for more information.