“The word adventure has gotten overused. For me, when everything goes wrong — that’s when adventure starts.”

– Yvon Chouinard

One misstep would have sent us careening down the mountainside, but caution was not a luxury we could afford, so we moved as fast as we could in the pitch darkness of night. Behind us, an angry mob from the village of Hispar was gaining ground.

The ice axe was still in my hands.

I was exhausted. I was supposed to be documenting the achievements of the scientists and explorers on our team. I had planned on climbing tall mountains and taking awe inspiring photographs. The rescue helicopter, the descent of the glacier, the sickness — none of that was part of the plan. Neither was being chased down a mountainside in the Himalaya.

There, in a remote valley in the middle of the night, the men who chased us were out for blood — my porter Ali’s blood, and my potentially-hepatitis-laden blood.

~~

The Karakoram mountains rise where present-day Afghanistan, China, Pakistan, and India come together — the result of tectonic collisions. It is a land of turbulence: earthquakes that change the faces of mountains; wars that change the borders of nations.

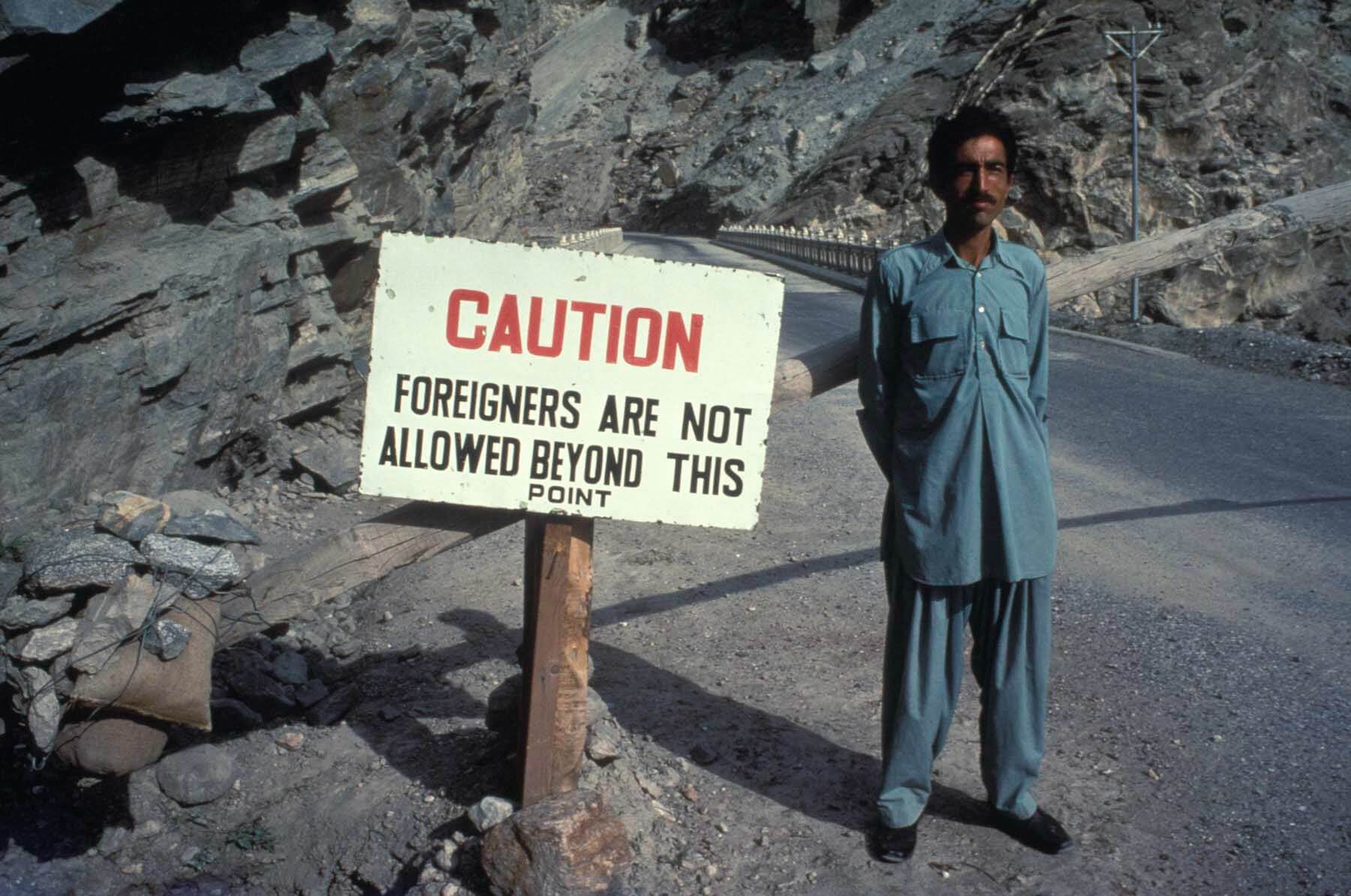

The eponymous highway winds treacherously across deserts and over mountains with frequent, sometimes-deadly, hairpin turns. Today, the Karakoram Highway connects Karachi, Pakistan on the coast of the Indian Ocean to Beijing, China. It is a 4,500-mile-long feat of civil engineering that many have traveled and some call the eighth wonder of the world. But back in July of 1980, the Karakoram Highway was newly built, barely completed, often unnavigable, and off limits to foreigners.

Frequent rock falls made portions of the Karakoram Highway a challenge on the best of days. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

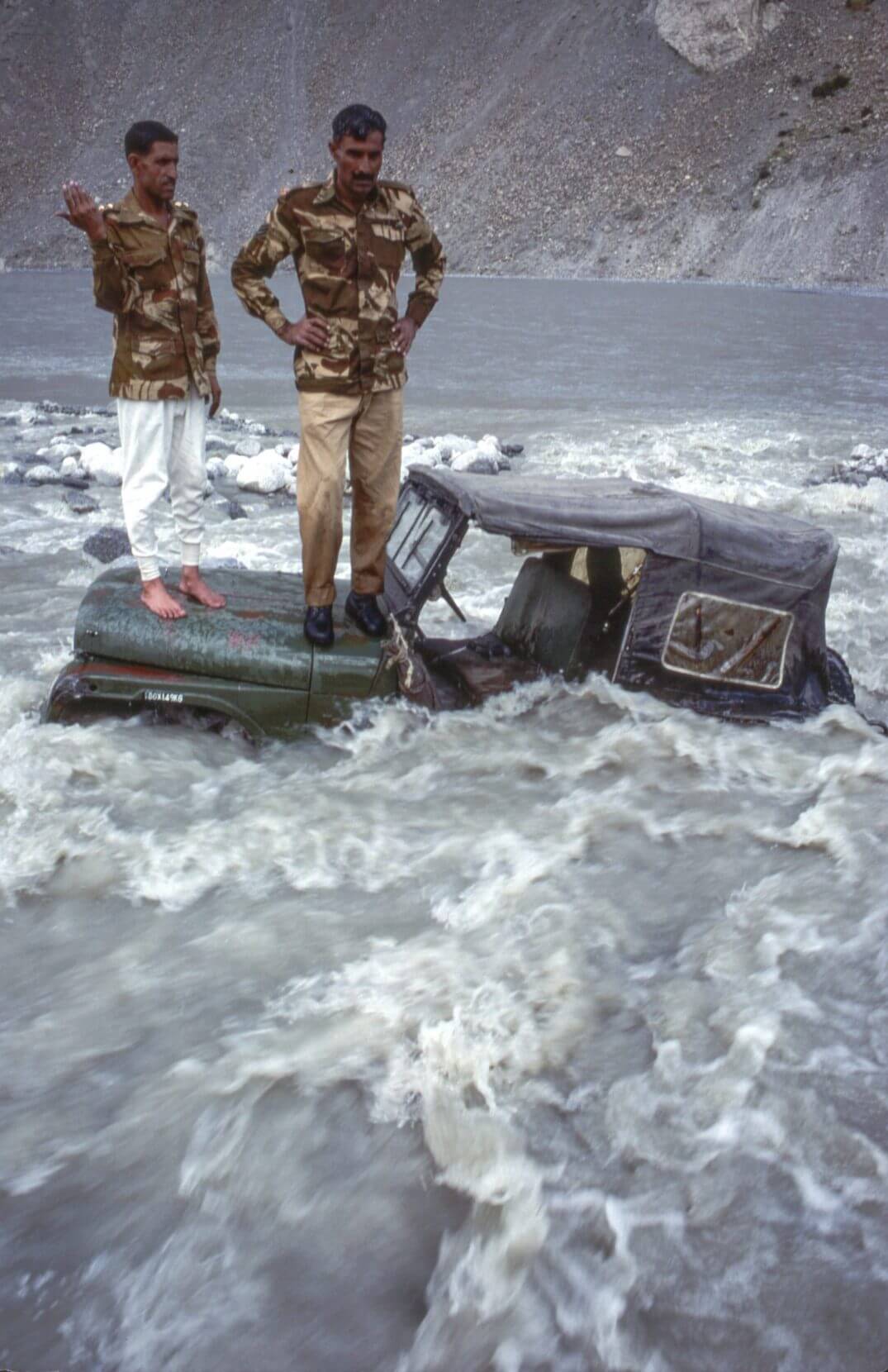

Melt water from the Gulkin Glacier washes away a section of the Karakoram Highway. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

When it opened, the Karakoram Highway was off limits to foreigners. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

I was there as part of an international team of scientists and explorers. I’d been invited to join the expedition as a photographer in large part because I had experience photographing in the Himalaya and was comfortable working at high altitude. In the spirit of exploration, we’d been sent to this wild and dangerous part of the world as part of the International Karakoram Project: the venerable Royal Geographical Society of London’s 150th anniversary expedition. We were there to conduct important work, but nothing in the Karakoram was ever that simple.

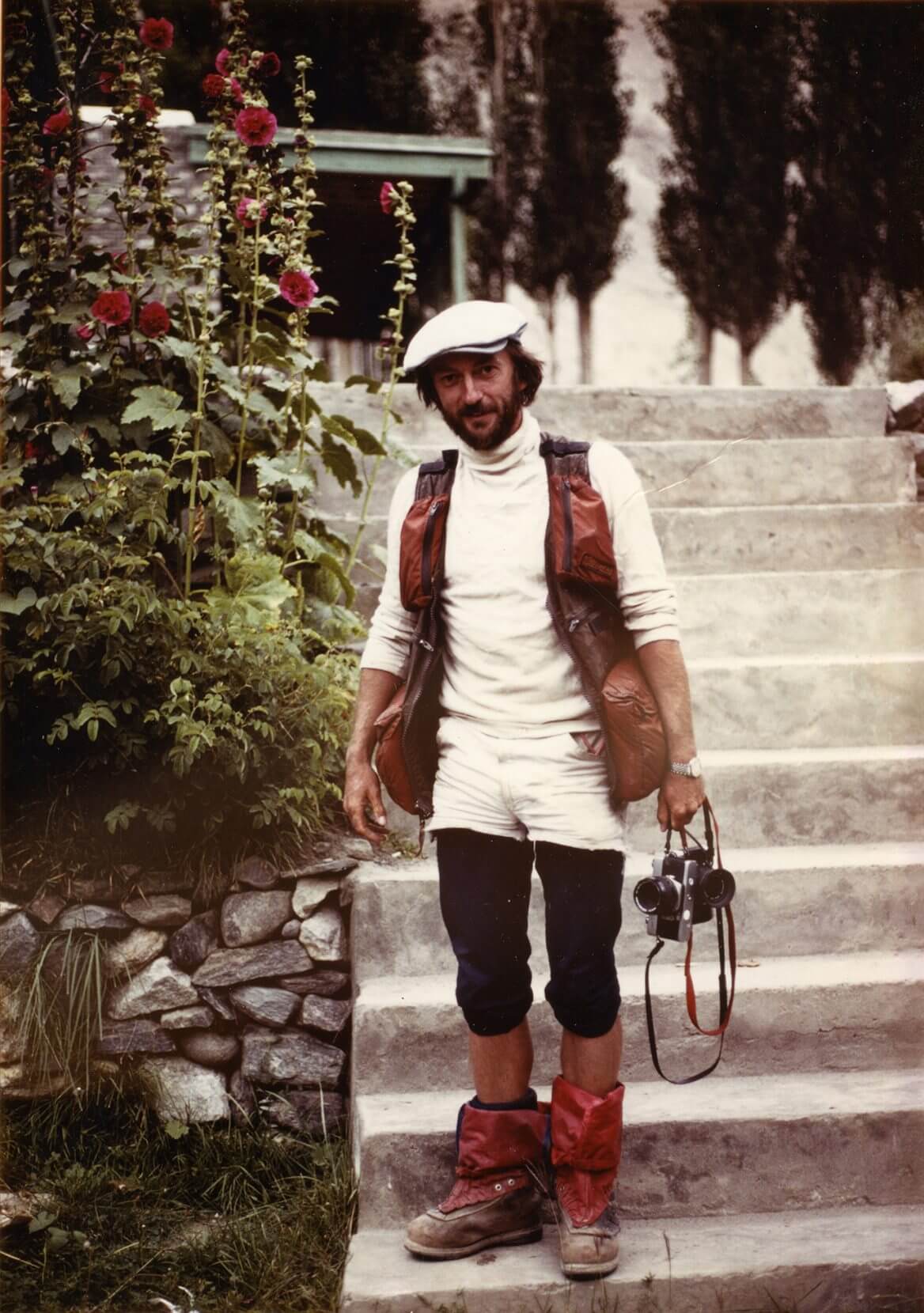

A young Robert Holmes in Hunza. PHOTO COURTESY OF ROBERT HOLMES.

We’d started our journey in Islamabad, eager to summit mountains. As a climber, driving in the shadow of Nanga Parbat — the 26,600-foot giant that, at that point, had claimed more lives than any other mountain on the planet — had given me goosebumps. But the old army truck we were in had been beat to hell building the Karakoram Highway and had not aged gracefully. It broke down every few miles. First, there was the flat tire that we couldn’t fix ourselves. Then the engine began firing erratically on random cylinders.

I thirstily gulped down glasses of filthy water — in the spirit of exploration.

“Maybe we should have kept the tire and changed the truck,” I joked as the problems multiplied and we began to run out of food and water.

And then there was the heat. July on the Karakoram Highway was hot: The temperature rose to 131° F. The steel-plated sides of the truck were untouchable in the searing heat, and the inside of the cab became an oven. I tried to avoid being cooked inside by traveling on the roof, but it didn’t work. Instead of being baked in the truck, I was roasted by the sun.

As we finally reached a village at the bottom of the valley, I thirstily gulped down glasses of filthy water — in the spirit of exploration.

~~

I had always wanted to see Snow Lake, the legendary destination of early explorers of the Himalaya. At almost 17,000 feet in altitude, the lake feeds the longest glacial system found outside of the polar regions — a 69-mile-long artery of ice formed by the Hispar and Biafo glaciers. I had always wanted to see Snow Lake, but not as part of a multi-day rescue mission.

Members from our expedition had established two camps in the area. The first, on a high meadow near the village of Hispar, was more robust and better manned than the second, which consisted of a single tent pitched on the highly-crevassed ice in the middle of Hispar Glacier.

The glacier camp on the HIspar Glacier with Snow Lake in the distance. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

Two Chinese glaciologists had been dispatched to the glacier camp to conduct radar ice-depth soundings and one of them, Zhang Xiangsong, was injured. What he thought was a minor ankle sprain had worsened and he was now tent-bound. Expedition leader Keith Miller, who considered himself a “hard man” in the mold of the great Himalayan explorers Shipton and Tilman, and who wore the same pair of pants for four months on our expedition before ceremoniously burning them at the end, was rerouted along with David Giles — one of our two doctors — and myself to assess Xiangsong and possibly rescue him.

Unsurprisingly, it sounded simpler than it was. First, we had to drive to the village of Nagar. From there, it was a four-day trek to Hispar Village and the meadow camp, before traveling to the glacier camp itself.

The village of Nagar gripped a mountainside high above a ferocious tributary that flowed to the Indus River. The road to Nagar wasn’t much of a road: It was a rough, unpaved trail cut into the mountain that was barely wide enough for our Land Rover. From one side of the vehicle, we could touch the mountain. From the other side, we could look out over a precipitous drop to the river below. At times, Keith’s nerves got the better of him and he insisted on getting out of the Land Rover and walking. On reflection, the abandonment of the Land Rover probably saved him from having to burn his pants sooner than he intended.

The road to Nagar from the Hunza Valley was narrow and treacherous. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

Keith’s “hard man” attitude extended to everything he did. From Nagar, he insisted on carrying all of his own gear and criticized me for using a porter, overlooking the fact that in addition to my personal gear, I also had my camera gear. Keith successfully shamed David into following suit and they both struggled along under heavy loads.

It wasn’t until long after the expedition was over, when I read Keith’s book, Continents in Collision, that I learned that by hiring a porter, I’d become “the focus of [Keith’s] envy.” I suspect that he became even more envious when he and David collapsed from exhaustion after the second day, and needed a full day to recover.

I contained the “I told you so” — barely — and continued on to Hispar alone.

The approach to Hispar was long, barren, steep, dangerous and hot. The tenuous trail barely made an impression on the steep mountain sides that were constantly swept by stone falls: It was like I was trekking through a bowling alley, hoping I wouldn’t be one of the pins. One slip would have resulted in a 200-foot fall straight into the icy waters that came off of the glacier and raged below.

Our route up the Nagar – Hispar valley. The trail was non-existant — constantly swept away by stone falls. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

The treacherous trail up to Hispar village. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

One of the many bridge crossings enroute from Nagar to Hispar. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

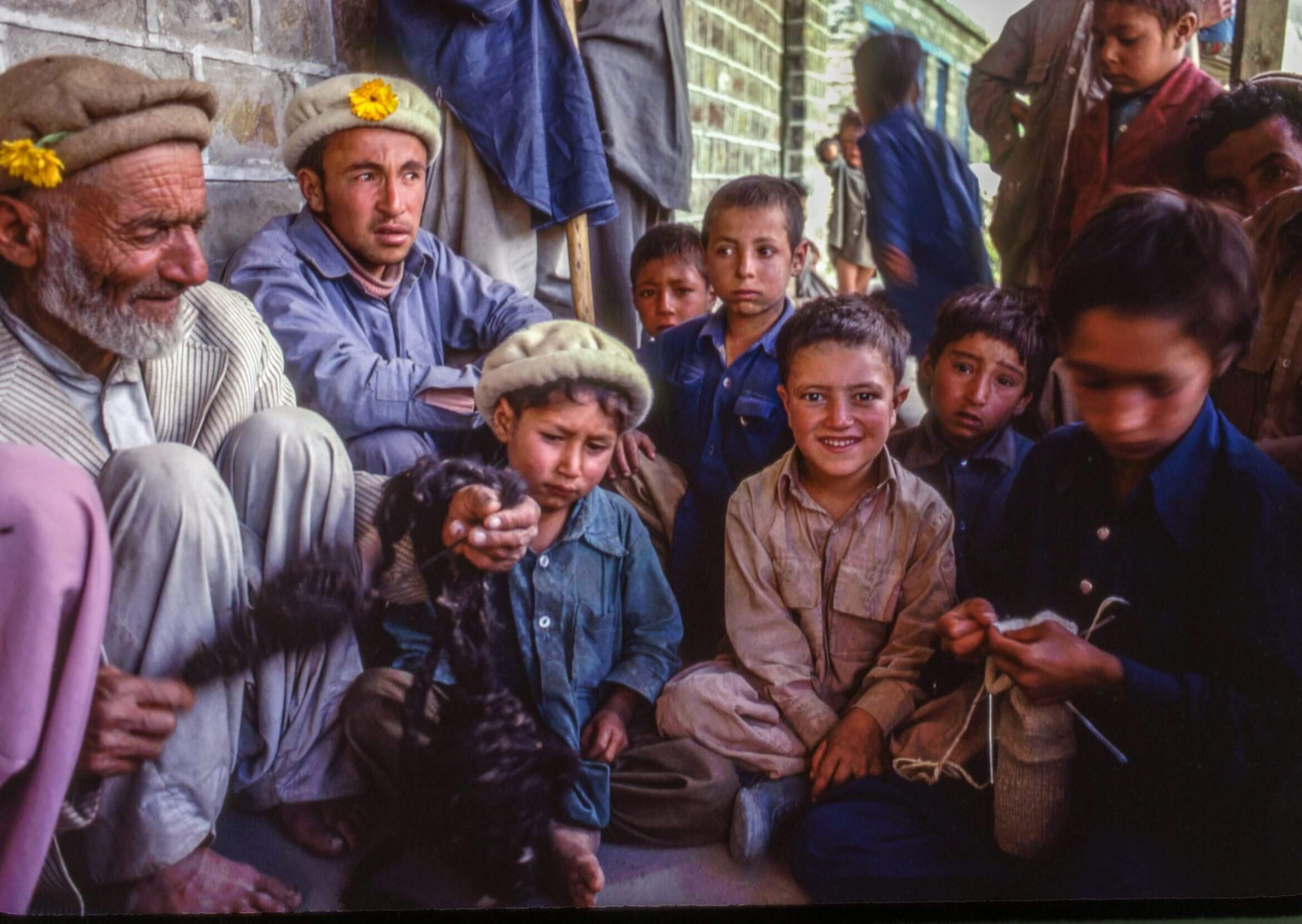

Among climbers, Hispar had an unenviable reputation. It was a village of 500 people clinging to the edge of the world. Hispar was once a penal colony for the Kingdom of Nagar; all manner of miscreants — from thieves to murderers — had been banished there. But long after the last criminal had been sent there, the village still had a reputation for creating conflict: Porters regularly attempted to shakedown clients, and two years prior to our visit, a Japanese expedition had all of their belongings stolen from their camp while they were on the mountain.

The village of Hispar had quite the reputation among climbers. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

Foreigners were never invited into the village itself. My old friend, photographer and climber Galen Rowell, told me that he had tried on several occasions to go into Hispar, but had never succeeded.

~~

When I made it to the meadow camp, I was surprised by the brilliant green vegetation surrounding it. It was incongruous with the monochromatic, glaciated landscape. I was also surprised — though by that point, I really should not have been — by the state of my team members at the camp: One of our glaciologists had contracted hepatitis and was a very sick; a member of the film crew had been bitten by a horse fly and his leg was showing signs of septicemia; and then, of course, there was Xiangsong, way out on the glacier with his injured ankle.

Also at the meadow camp was Paul Nunn, another member of the film crew. He was a friend and old climbing buddy of mine from England, but he was also a legendary British mountaineer who had helped establish the glacier camp where Xiangsong was marooned. He would take David — who had eventually joined us at the meadow camp — and I out to fetch Xiangsong.

As old friends are wont to do, Paul and I chatted away as we crossed a jumbled river of crevasses, serracs, and massive boulders, making our way to the single, red tent that sat somewhere in the middle of the glacier. We spoke about the climbing scene in the United Kingdom and old climbing friends of ours, reliving the numerous beer-fueled evenings we had spent at the Moon Inn in Stoney Middleton, Derbyshire — a weekend watering hole for climbers. I was content to relinquish responsibility to Paul as we crossed the confusing vista of rock and ice. Surrounded by some of the world’s highest mountains, I enjoyed the conversation and an overdue respite from the adventure.

Paul Nunn and David Giles finding their way across the Hispar Glacier. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

Zhang Xiangsong and Dong Zhi Bin waiting for rescue at their camp below Snow Lake on the Hispar Glacier. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

Xiangsong sat outside the tent with Dong Zhi Bin, affectionately known at “Lao Dong” (old Dong), anxiously waiting for us to arrive. Food was in short supply. The sprain turned out to be a fracture and carrying Xiangsong across such dangerous terrain was not an option, so we radioed for a helicopter. At that altitude, we knew it would be a risky operation, but it was also the best option.

An army helicopter appeared down the valley. At least we thought it did: The scale of the landscape was so enormous that the helicopter was difficult to make out. It was a tiny spec against the huge mountain walls, but the thud, thud, thud of its rotor blades confirmed that it was getting close. David and Xiangsong climbed aboard, but at the last moment Paul jumped on as well — much to my surprise and alarm. The helicopter disappeared into the mountains until even the sound of the rotors faded to nothing.

Lao Dong and I were left utterly alone, only creaks in the slowly moving ice interrupting the otherwise absolute silence.

~~

Lao Dong had no mountain experience and was not exactly in the best physical shape. I, of course, was the epitome of health, except that I was starting to wonder if I, too, had hepatitis. Somehow, I had to get both of us back to camp across the glacier, with only the vaguest idea of where to go. I had a radio and hoped Keith would be able to talk me through the route. Lao Dong struggled to keep up both on the steep ice and over the gigantic boulders that littered the glacier. Our progress was painfully slow, and not helped by knowing that I was blindly making our way back to safety. I didn’t share this with Lao Dong.

Meanwhile, back in the comfort of meadow camp, concern was rising: “As the day progressed,” Keith later wrote, “our anxiety for Lao Dong and Bob increased. They had only a little Alpen to sustain them, and Bob’s voice on the radio was beginning to indicate more than weariness. Because of his experience on Everest, I initially gave the matter little thought, but as time passed and his voice echoed more and more concern, the tension increased. I had already noted that Bob had been in poor health on the way up, and was probably not fit. Furthermore, he was not sure of the way, and by this time he knew there was no identifiable route and it was simply a matter of climbing one moraine cone after another and hoping to make steady progress down stream through a maze of rock piles.”

Negotiating obstacles on the Hispar Glacier. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

“No identifiable route” was putting it mildly. Slowly, carefully, painstakingly, we made it back and Lao Dong gave me a huge hug in his relief.

We were safe on terra firma, and I was now pretty sure that I had hepatitis. I felt weak. I had no energy. And I was evacuating my bowels with unpleasant frequency. No one objected to me immediately getting off the mountain and heading back down to our main basecamp at Hunza as quickly as possible.

I made it down to Hispar and collapsed in a rest house on the edge of the village. There was no way I was going anywhere for a few days. The villagers went out of their way to look after me. Surprisingly, they invited me into their village and even into their homes. They brought me food, made sure I was comfortable, and attempted to nurse me back to health, but more than anything, I needed to rest.

The villagers in Hispar came to the aid of an ill Robert Holmes. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

So, naturally, I received a note from Keith who was still up at the meadow camp. The Hispar porters had made excessive demands, so Keith had fired them — all of them — and refused to pay them. Keith wanted me out of Hispar immediately and had radioed down to our basecamp in Hunza to send a porter to rescue me.

The porter from Hunza, Ali Haider, was in his late teens and tough as nails. Like many of the Hunza men, in lieu of boots, he wrapped sheep skins around his feet to trek through the mountains. I was delighted to see him, but the men in Hispar were not.

Ali Haider wrapping his feet in goat skins. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

They immediately put Ali and I under house arrest.

The Hispar guest house where author Robert Holmes and Ali Haider were held. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

~~

A villager stood guard outside the simple cinder block guest house. For the first two days, he never let us out of his sight. On the third day, we concocted an escape plan and surreptitiously packed our backpacks. It was Ramadan and just as it was getting dark, the guard left us to go eat. We donned our backpacks. I hung a camera around my neck and grabbed my ice axe, and we crept out to the trail. If all went well, the villagers wouldn’t notice our absence until morning. But this is an adventure story, and so all did not go well.

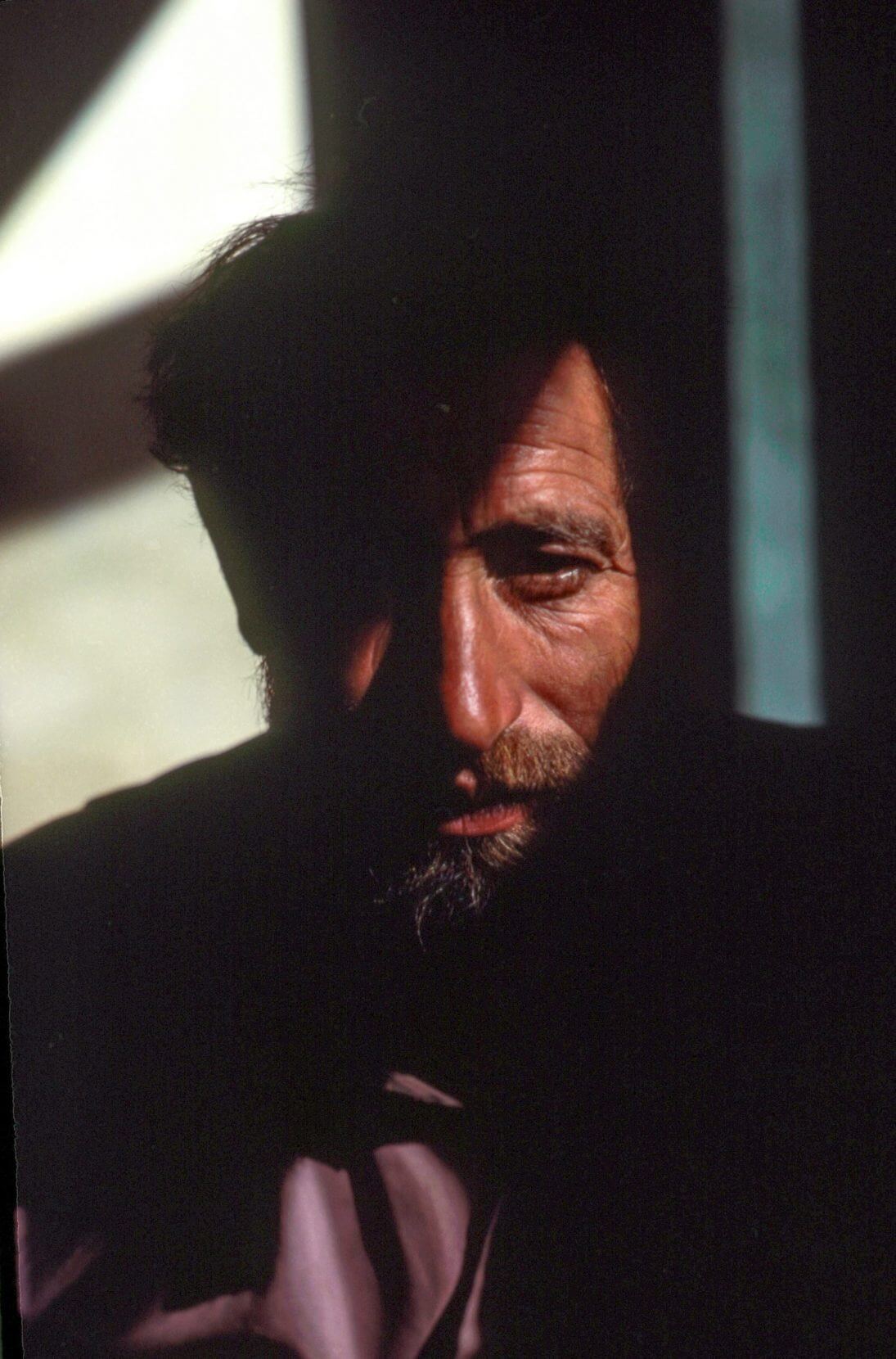

A portrait of the man who stood guard at the Hispar guesthouse while Robert Holmes was under house arrest. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

A trace of moonlight somehow managed to seep through the thick clouds that covered the sky that night, but still, it was incredibly dark. Unfortunately, it was quiet, too. When we accidentally dislodged a rock and sent it scattering below, it was loud enough to draw the attention of three villagers, who came chasing after us.

They caught up with us just before we reached a dangerous, rickety wooden bridge. They grabbed Ali, manhandling him, shouting, pushing him to the ground. I was carrying my ice axe and I did the only thing I could think of. Like a madman, I swung it wildly over my head, yelling. I thought little of what would happen if I actually made contact with one of the villagers. Thankfully, the sight of a crazy, ice-axe-wielding foreigner seemed to do the trick and they fled.

One of the many rickety bridge crossings below Hispar Village — tenuous even by daylight. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

I hoped that would be the last we saw of them. Ali, however, was convinced that they had just gone back for reinforcements, so we hightailed down the tenuous trail that had taken us so long to negotiate on the way up. Adrenaline pumped through me. I still had the camera around my neck. A lens cap popped off and disappeared into the darkness, clattering down to the river. We couldn’t see the water below us, but we could hear its distant roar.

We lay down on the dirt floor of the cave, not bothering with sleeping bags. I wanted to be able to flee in an instant.

Falling rocks whistled past us as we ran down the mountainside. I was scared, as much as anything because Ali was scared — not of the terrain, though he should have been, but because if the men from Hispar caught us, it would only take one push for the both of us to join my lens cap a couple hundred feet down in the icy waters, never to be seen again. Just another unfortunate mountain accident.

At first, I thought Ali was being paranoid, but then we heard voices in the distance and could see the dim flicker of lights coming toward us. Fear is a great motivator. Survival mode kicked in and I discovered resources of energy I didn’t know I still had. Ali told me he knew a cave where we could spend the night. It was high up on the mountain and only some shepherds from his village knew where it was. I don’t remember now, years later, how we communicated. Ali didn’t speak English and I certainly didn’t speak Urdu but somehow he was able to make himself understood. I found it impossible to believe that our pursuers didn’t also know this cave.

It wasn’t a particularly cold night, and we lay down on the dirt floor of the cave, not bothering with sleeping bags. I wanted to be able to flee in an instant.

I was unable to sleep. All night, I lay awake, listening for our pursuers. None came. Well before the first weak light of dawn lightened the sky, we set off again, moving swiftly down the steep trail towards salvation, never quite sure if we were still being followed. At last, we collapsed into Nagar.

The journey had taken us four days on the way in. We had just completed it in less than 24 hours.

~~

Back at basecamp, I discovered it wasn’t hepatitis that I was suffering from, but amoebic dysentery. It must have been from the filthy water I had drunk several weeks prior on our drive from Islamabad.

Finally, I could rest and partake of a strong dose of Flagyl that knocked the amoeba right out.

Finally, the damn death-defying adventure was over.

And these days, now that adventure travel is de rigueur, I think I’ll opt out. Saving lives? Adrenaline-fueled escapes? A quiet vacation with a tall drink on a sun-washed beach sounds preferable to me.

But do you know what happens when the waves are lapping the shore, when I am calm and content and everything goes well? I get bored.

So, I wait. I wait for adventure to begin again.

On the Hispar Glacier. PHOTO: ROBERT HOLMES.

Robert Holmes

From the 1975 British Everest Expedition to the vineyards of the world, Robert Holmes’ career as one of the world’s most successful and prolific travel photographers has extended more than 40 years.