Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

Under a leaden sky, the Captain Cook pulls away from Saigon’s bustling colonial port, passing between long rows of painted fishing boats that rock in its wake, then gathers speed as it forges out into the South China Sea.

On deck, 11-year-old Irma Cazes watches the land of her birth gradually receding, unsure if she will see it again. In that moment, she feels little sadness for all that her family has had to leave behind, though she’s not oblivious to her parents’ quiet grief nor the harrowed expressions of the other adults around her. She will only truly understand their suffering much later. For now, she is embarking on the adventure of a lifetime. She is discovering the world. She is unbound.

Fragments of the ocean liner’s three-week voyage sear themselves indelibly into Irma’s memory like freeze-frame images to be recalled in precise detail many decades later. The pyramids rising like vast sand dunes on the horizon in the Gulf of Aden. Sicily’s volcanic Mount Etna erupting into the sky like a fire-breathing dragon. The hulking whales that explode from the ocean depths. The sweet, milky tea and cream-filled cakes laid out in the mess each afternoon. The vault of stars at night.

Then finally, her first sight of France as the boat pulls into Marseille on an unseasonably cold spring day in April 1956.

After a few nights in a transit hotel, Irma’s family, along with the hundreds of other disoriented passengers, are sent west by rail and road deep into this strange place, this long imagined yet unknown fatherland. Through her window, Irma marvels at the perfect columns of towering plane trees, the rolling pastoral hills, the rugged olive groves, and the ceaseless expanses of perfectly trained vines. All of this, she thinks, is somehow part of me.

The long journey finally ends at an austere military barracks beside the languid Lot River on the outskirts of the small market town of Sainte-Livrade in southwest France.

As Irma’s parents unload the family’s few possessions from the bus, she takes in her new home: three dozen long, low-slung concrete buildings with corrugated zinc roofs laid out in an orderly rectangular grid around a central square and a scruffy soccer field. Beyond a wire perimeter fence, the barracks are hemmed in on all sides by flat, featureless farmland, across which a light breeze now carries the faint but defiant sound of children’s laughter.

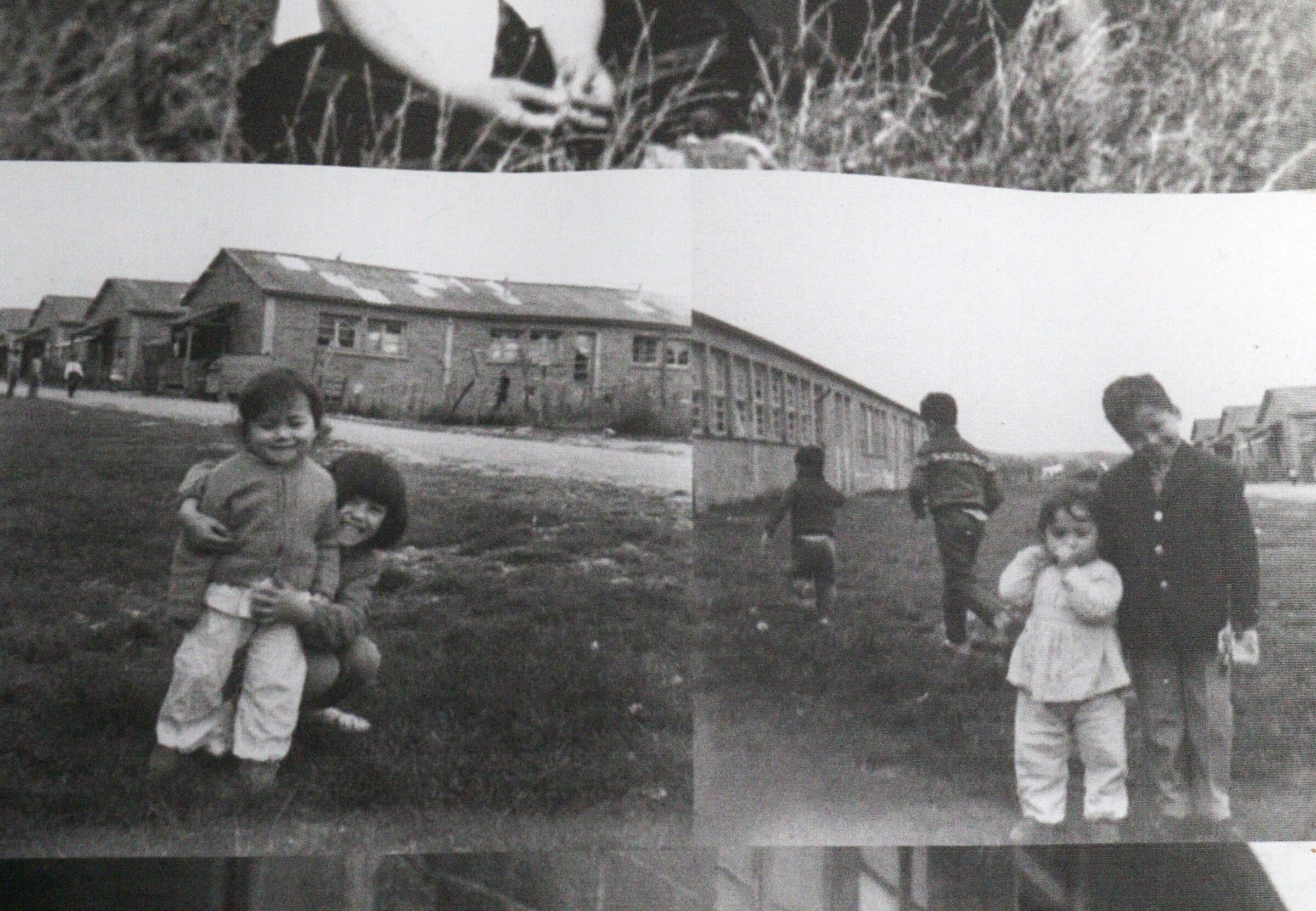

When CAFI’s first residents arrived at the camp, many of the children were too young to fully grasp what their families were leaving behind. Photo: Christopher Clark.

~~

On September 2, 1945, just hours after Japan surrendered to the Allied forces, bringing an end to the Second World War, the emaciated and goateed Communist revolutionary Ho Chi Minh ascended a podium in the middle of Hanoi’s Ba Dinh Square, surrounded by a euphoric crowd almost half a million strong.

“A people who have courageously opposed French domination for more than eighty years, a people who have fought side by side with the Allies against the fascists during these last years, such a people must be free and independent,” he said.

A stone’s throw away and a mere seven months before this fateful day, when Hanoi was under Japanese control but still administered by French officials, Irma was born. Before she had even learnt to crawl, her world had been turned upside down. Her father, who was French Chinese but born and raised in Hanoi, had served in the French army, fighting against Ho Chi Minh’s guerrillas. He and his family, who he had endowed with French citizenship, now effectively found themselves on the wrong side of history.

France stubbornly resisted the widely popular Vietnamese independence movement, setting the stage for a bloody, ill-fated eight-year war that would claim more than half a million lives and end in a humiliating, regime-ending rout of French forces at Diên Biên Phu in 1954. This defeat, and the scything in two of Vietnam that resulted from the subsequent Geneva Accords, would pave the way for the Vietnam War.

As the victorious Viet Minh marched back into Hanoi, Irma’s family, fearing violent repercussions for their affiliation with the vanquished colonial regime, fled the city with little more than the clothes on their back. Joining a caravan of hundreds of thousands of internally displaced people, they made their way south toward Saigon to await their eventual evacuation to France.

Throughout 1956, as many as 400,000 people would leave Indochina; depending on the estimate, between 35,000 and 54,000 Indochinese repatriates, primarily the naturalized widows and children of fallen French soldiers, were sent by boat to France.

Many would never return to their native land. By the same token, some would never entirely leave it behind.

~~

I pass between the ruins, trying to imagine these alleyways thrumming with the sound of children.

On a frigid February afternoon, I take off my shoes and step inside the small pagoda, where I am greeted by the smell of incense and the sound of soft Buddhist chants playing from an old CD player in the corner. Even as a staunch atheist, it is hard not to immediately feel at peace in this place of worship, surrounded by the warm red fabrics, the candles, the kaleidoscopic flower arrangements, and the bronze statues of smiling Buddhas. With no windows to the outside world, it is also easy to almost entirely forget where I am.

The pagoda is one of the last remaining vestiges of the euphemistically named Welcome Centre for the French of Indochina, CAFI for short. Or, more appropriately, “the camp,” as many locals still call it, with a complex mix of tenderness and torment. As the camp’s unique history and cultural identity have become increasingly endangered, the pagoda continues to provide an important link to the camp’s origin story, serving as a kind of portal between two different worlds and temporalities.

Now 79 years old, Irma, diminutive and soft-spoken with a round face, white hair, and gold-rimmed glasses, serves as one of a small handful of devout and dedicated custodians of this modest religious node. To her knowledge, it is the only place in Europe where some practice an ancient heterodox Buddhist rite called Len Dong, whereby adherents become mediums for various spirits.

“We fought very hard to keep this place alive,” Irma tells me, looking around the room. “It is like a tree, and our story is its roots. If we don’t protect this tree, then one day, no one will remember us. We will be swept away.”

Irma Casez was among the first residents of CAFI. Her own story is intimately entangled with that of the camp’s. Photo: Christopher Clark.

~~

Paul Landré is shrouded in smoke and steam, puffing on a crooked rolled cigarette as he stirs a large pot of potatoes, backlit by soft winter sunlight streaming through the windows of his home on the fringes of the camp. A couple of generations of forebears preside over this domestic scene from four picture frames hanging above a small shrine of miniature Buddhas and a statuette of the Virgin Mary. Three of the black and white photos show people with striking Southeast Asian features and traditional attire. The fourth is the obvious odd one out: a boyish Caucasian man in French military uniform.

Paul never knew his maternal grandfather. Not long after the photo was taken, in 1950, the young soldier was killed by the Viet Minh, becoming one of the more than 92,000 fatalities on the French side of the First Indochina War. He is the reason both Paul and I find ourselves here today, talking about the distinctly unusual trajectory of Paul’s life.

“My ass is between two chairs,” Paul proffers as a summary of his particular position: Not quite French, not quite Vietnamese. Historically bound to a country that no longer exists. But above all, for better or worse, still improbably tied to these storied 17 acres on the edge of a rural French backwater.

Multimedia journalist Christopher Clark visited Paul Landré in his home to try and understand what CAFI continues to mean to the people who live there. The four photos above Paul’s shelf provide context for the life of a man stuck between two countries, one of which no longer exists. Photo: Christopher Clark.

Now a wry and spritely 62-year-old with deep smile lines and short graying hair, Paul talks about growing up in the camp with a sunny nostalgia. He excitedly recalls stealing ripe plums from the surrounding farms and getting into teenage dustups with boys from town for flirting with “their” girls. At one point, he’s so animated by his memories that he knocks over a full cup of instant black coffee he’s just set down on the kitchen table.

“I think it’s hard for people from outside to understand, but I had a happy childhood here,” he says. “It was basically a ghetto, but it was also a very special and extremely close-knit place.”

Paul was just 18 days old when he first arrived in the camp in 1962. CAFI had initially been intended to serve as a temporary home – a “port of call,” as a local newspaper had put it shortly before the repatriates’ arrival. But by the time Paul was born, it had already been six years since his grandmother and her three teenage children had been deposited here in the spring of 1956.

Though Paul’s young mother had managed to finish high school and leave the camp to seek work in Paris, she fell pregnant and, unable to support the baby on her own, sent Paul back to the camp to live with his grandmother.

Paul’s subsequent path was effectively the opposite of many of the camp’s children. “Most of them did their schooling here and then left for the big cities or went abroad in search of work, where they then stayed,” he says. “Whereas I was sent away to boarding school at age seven and then moved back to the camp when I finished at the age of 18. I’ve been here ever since – more than 40 years now. I’ve never really wanted to be anywhere else.”

Over two and a half years, Clark built a relationship with Paul Landré, who opened up his home and his life to help tell the story of CAFI. Photo: Christopher Clark.

About six years ago, Paul started collecting scrap metal and other salvaged objects and materials he found around the neighborhood or picked up at flea markets, turning them into an incongruous array of ornate lamps.

A couple dozen of his creations, which incorporate everything from a clothes iron and a mannequin head to precious stones and intricate stained-glass patterns, are informally displayed on a mahogany dining table and two bookshelves in the somber lounge next door. I’m immediately moved by these solid and strangely beautiful items made from disparate and discarded things, casting new light in a dimly lit corner.

~~

Irma pulls out two plastic chairs, and we sit down on either side of a small table in the corner of the pagoda, where I ask her about the childhood years she spent in this unlikely and oft-forgotten place.

Despite her advanced age, Irma’s memory of that time remains as sharp as a tack. She remembers the precise configuration of the cramped four-room living quarters she shared with her grandmother, her parents, and her eight siblings. She remembers huddling together against the cold on winter nights. She remembers the way the local boys looked at her and her sisters “like strange, exotic beasts.” And she remembers her father’s near-constant anger and chagrin, and her sense that something had broken inside him that could never be fixed.

In Hanoi, Irma’s family, like most of the families at CAFI, had lived a comfortable upper-middle-class existence, with five household staff, including a live-in cook and valet. Here, they were forced to live without heating and running water and subsisted on meager food rations. They had to obtain military authorization for any movement beyond the camp and adhere to a 10:00 p.m. curfew.

To add insult to this already considerable injury, in 1959, a ban was instituted by government decree on anything that qualified as an “outward sign of wealth,” the argument largely being that a population relying on state subsidies should not be seen to be profiting from them. The ban included televisions, washing machines, and cars; residents could be asked to leave the camp if they were found in possession of such illegal items.

Beyond a wire perimeter fence, the barracks are hemmed in on all sides by flat, featureless farmland, across which a light breeze now carries the faint but defiant sound of children’s laughter.

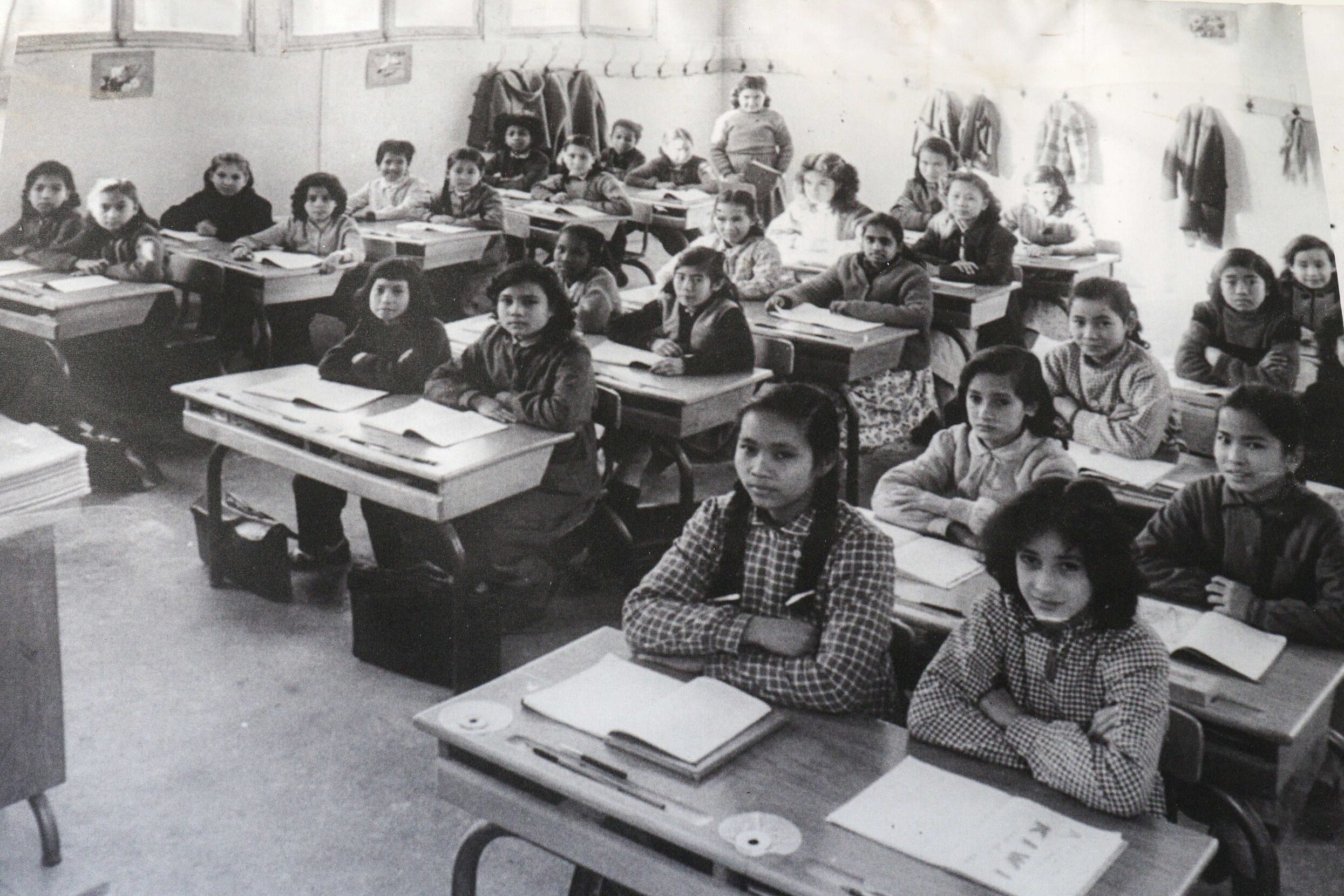

Despite the harsh environment and the palpable hardship, Irma maintains that she has “very fond memories of childhood” here. As I try to make sense of this apparent contradiction, I wonder if it relates to the children’s numerical advantage: Of the approximately 1,200 repatriates that were installed at CAFI by early May 1956, almost two-thirds of them were children, most under 14 years old. This would have given the children a certain power, and as more and more of their parents were forced to take up poorly paid work on the surrounding farms, CAFI became theirs. Over time, I would come to realize, the children’s strength in numbers would also give them a certain sovereignty over the enduring narrative of this place.

In the image on the left, a young Irma Casez smiles while another child, possibly a sibling, hugs her. Photo: Courtesy of Christopher Clark.

I detect something pained in Irma’s expression, a heaviness behind her eyes. I want to probe further, to try to expose the fault lines in her sweeping summation of childhood happiness. I want her story and that of the camp to be only bleak and, therefore, simpler.

But then something strikes me: Surrounded by so much pain, loss, and dislocation, Irma managed to create a kernel of joy that no one could take away from her.

~~

“It is like a tree, and our story is its roots. If we don’t protect this tree, then one day, no one will remember us. We will be swept away.”

The revolts had been rumbling for months. Now, after more than a decade of neglect, a number of disenfranchised youth had turned to violence in an attempt to raise public awareness of the forgotten plight of their camp. On the morning of August 16, 1975, when Djelloul Belfadel, a 42-year‐old official of the Union of Algerian Migrant Workers in Europe, finished his weekly grocery shopping in the village of Firminy, he was abducted and driven five hours southwest.

Belfadel was held hostage by three men and a woman armed with hunting rifles in the administrative center — not of CAFI, but of Bias, a camp located less than ten kilometers away. For some years, Bias had been used as an auxiliary camp for around 600 Indochinese repatriates. But after the end of the Algerian War of Independence in 1962, it was cleared to make way for Muslim Algerians who had fought on the French side; some of these men, known as “harkis” from the Algerian-Arabic dialect word for soldier that is now sometimes seen as derogatory, had also served in Indochina. Around 1,200 Algerian repatriates would ultimately end up at Bias, including 600 children.

Belfadel was the latest victim in a series of abductions over the preceding months. Shortly after Belfadel’s abduction, the state promptly deployed 500 riot police to the camp. Police helicopters buzzed overhead. Journalists flocked to the scene. Whatever happened next, Bias would be ignored no longer.

~~

I leave Paul and set out on foot with my camera to get a better lay of the land. Just behind Paul’s house, one of the bean farms — where so many of the repatriates, including his grandmother, once toiled — has now become an equestrian center. A couple of horses are grazing peacefully in a grassy meadow, separated from CAFI by a mesh wire fence.

I continue around the neighborhood’s perimeter, passing a squat, red-doored chapel that was installed by a French missionary in the early 1960s to serve CAFI’s minority Catholic flock. On either side of it, four barracks from the original camp extend in long, straight rows to the Buddhist pagoda on the other end.

Today, the only inhabitants of these dilapidated buildings are a clowder of unkempt cats. Almost all the windows have been smashed in, and the doors are haphazardly boarded up with scrap wood. In some places, dense foliage has sprouted from gaping holes in the roof. I pass between the ruins, trying to imagine these alleyways thrumming with the sound of children.

The old barracks, which no longer house residents, have fallen into a state of disrepair. For a variety of reasons, the fate of CAFI was different than that of the nearby camp of Bias, but in both cases, it took shocking events to bring change. Photo: Christopher Clark.

I make my way over to Petit Saigon. Another of the last remnants of the original camp, it is an Asiatic grocery store that now doubles as a popular Vietnamese restaurant. The restaurant is in the midst of a busy lunchtime service. The owners, a pair of gregarious sisters who grew up in the camp, seem to know almost everyone. The general mood of the place is convivial and familial. As I eat hot pork nems and sweet cashew chicken stir fry and observe the diverse clientele, I feel increasingly disoriented by the cognitive dissonance of this place. I came here to tell a tale of affliction and injustice, yet CAFI keeps resisting any such reductiveness. For how much longer, I wonder, as the outside world continues its steady encroachment, adding its new overlays to the palimpsest.

I pay my bill and walk back toward my car, with the afternoon light slowly beginning to fade. Just as I am about to clamber into the driver’s seat and head home, I see Paul sitting on a wooden bench on a patch of open grass away to my left. He beckons me over, inviting me to sit down next to him.

“I like to sit on this bench because if I look straight ahead then I only see the old buildings,” he says. He draws on his cigarette, then exhales deeply, taking in the view. “From here, everything looks exactly as it used to.”

~~

After three days of tense negotiations between his captors and the state — during which the former demanded proper housing and efforts to allow the Muslim Algerians to travel freely between Algeria and France — Belfadel was eventually released.

The state promptly handed the site over to the local authorities, who closed the camp the following year to replace it with social housing.

This outcome certainly did not go unnoticed in CAFI. Perhaps now, the Indochinese repatriates thought to themselves, our time will also finally come. Years later, in 1981, CAFI was purchased by the local authorities, like Bias before it. But this would prove to be another false dawn.

Today, when I ask repatriates why CAFI was left to its lonely deterioration for another three decades after the razing of Bias, many cited their reluctance to resort to violence as a primary factor.

I want her story and that of the camp to be only bleak and, therefore, simpler.

However, the Vietnamese sociologist Trinh Van Thao, who wrote his dissertation on Indochinese repatriates in France, has suggested the different treatment was partly down to mere numbers: While he estimated that approximately 35,000 people were ultimately repatriated to France after the Indochina War, almost three times as many harkis, plus their families, had sought refuge in France by the end of 1962.

There was also a different political dimension: Unlike the harkis, with few exceptions, the Indochinese repatriates were not soldiers. For the former, this added an additional layer to the sense of betrayal they felt at their treatment in France. These differences have continued to influence the discourse around France’s colonial legacy even in recent years. As journalist Bruno Icher wrote for Liberation newspaper in 2004, “If the scandal of the harkis returns regularly to the spotlight (with little effect), that of the Indochinese repatriates is conspicuous in its absence from debates.”

Nina Douart-Sinnouretty, another child of CAFI’s second generation, has another theory: “The defeat at Diên Biên Phu was such a humiliation for France that the country did everything it could to erase the memory of the war in Indochina, and us with it,” she tells me over the phone. She highlights the fact that even when the country passed a controversial law in 2005 that sought to “bring recognition of the national contribution of repatriated French citizens” — while also requiring teachers to teach the perceived positives of French colonialism — the bill’s first version had to be amended. There was a glaring omission from the list of “former French departments:” Indochina had been left out.

A small memorial commemorates the combatants and victims of the French Indochina War. Photo: Christopher Clark.

~~

On New Year’s Eve 2005, a devastating fire ripped through CAFI. An 87-year-old repatriate named Liliane Andrea was killed in her sleep in the same ramshackle unit she had inhabited for the past 49 years; several of her neighbors were left homeless. In a short news item about the incident in the local Depeche de Midi, the mayor of Sainte-Livrade accused the state of dragging its feet on backing a proposal the cash-strapped local authorities had put forward in 2004 to finally demolish the barracks. The remaining repatriates, whose population had by then waned to around 100, would be rehoused in new social housing units.

That same year, Irma’s father died at 83 years old, his health having steadily deteriorated since he’d had a stroke two years previously. While all his children had long since moved away to Toulouse or Bordeaux, the two nearest big cities, he had stayed in the camp until the bitter end. By that point, many of the first generation had succumbed to sickness and disease; both Paul and Irma told me that a lot of people died from lung problems, pointing to the presence of asbestos and lead in the camp’s buildings.

“All wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.”

With the health and public safety risks increasingly hard to ignore, the reconstruction of the camp finally began in earnest in 2008. Local journalist Joël Combres later captured the community’s ambivalence about the change in a special issue on the history of the camp for a regional quarterly: “‘Too late,’ believe some, remembering the hardships endured since 1956 by the so-called ‘rights holders’ — the now-grandmothers whom the nation abandoned to their fate as young women. ‘Too early,’ say others, regretting that their forebears were not allowed to die in peace inside the brick and sheet metal structures they had humanized before the great upheaval began.”

True to form, the authorities initially failed to include the remaining repatriates and their descendants in the planning process for the new community. But after tireless campaigning by Irma and others, it was ultimately agreed that the transformation should honor the original camp. Ultimately, many of the 92 new social housing units were installed in long, low-slung buildings that bore a passing resemblance to their antecedents.

At the center of the camp, four of the original listed buildings, as well as the pagoda, were also left standing as part of a so-called “place of memory” — a place where both the joy and pain of the camp could continue to co-exist as diminished but still-defiant bedfellows.

~~

Irma’s brother Charles Cazes (standing) and Charles Maniquant (seated in wheelchair) proudly display their military ribbons and medals. For Clark, the two men sparked a shift in perspective. Photo: Christopher Clark.

Six months after my first visit, I drive back to Sainte-Livrade on an oppressively hot afternoon in mid-August. I check into a small, dank Airbnb and then walk into town for a cold beer.

The whole place seems to be in a kind of soporific stupor from the heat. The streets are almost entirely abandoned, save for a few pockets of shirtless French-Algerian men drinking fifths of beer in the shade on the steps of the central market hall.

The following morning, I make my way back to CAFI for the unveiling of a bronze plan-relief of the camp. The ceremony marks the opening of this year’s August festivities, which commemorate the anniversary of the repatriates’ arrival in France; being the traditional holiday period, the dwindling repatriate population is swelled by its dispersed progeny and their families. It’s now 66 years since the first buses of repatriates — including Irma’s family — arrived here.

About 150 people, including local dignitaries, gather around the small memorial, which sits on a scorched patch of grass at the center of the original camp. Presiding over the relief’s intricate rendering of the old barracks are the hunched-over figures of five women in conical non la hats, recalling the hard labor that many of the repatriates were forced to carry out on the surrounding farms. There is also a small plaque that reads simply, “for our mothers.”

In a short speech, the project’s architect, Nicolas Revue, himself a child of CAFI, evokes the camp’s “particular mix of joy and pain.”

Once the formalities are over, a number of former residents crowd around the relief, pointing out to their friends and family where they used to live and the precise locations of childhood memories.

She is embarking on the adventure of a lifetime. She is discovering the world. She is unbound.

I notice Irma on the edge of the crowd and go over to say hello. She introduces me to her younger brother Charles, an ex-legionnaire. He is chaperoning a wheelchair-bound fellow ex-combatant, a nonagenarian by the name of Charles Maniquant, who tells me he served in both Indochina and Algeria. Both men are dressed in full military regalia for the occasion. Initially, I’m uncomfortable with the proud display of allegiance to a country — and an empire — that was so quick to cast men like Charles Maniquant aside.

But then I think of a quote from Viet Thanh Nguyen, the Vietnamese-American Pulitzer Prize winner: “All wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.”

In a way, I suddenly realize, Charles in his uniform simultaneously embodies both fights. I, on the other hand, am slowly coming to terms with my own inevitable defeat as I finally let go of my stubborn desire to impose a simpler narrative. I’ve wanted history to be simpler – its contours, its heroes and villains, and perhaps above all, its victims, to be more clearly defined. But now I begin to accept CAFI in all of its bittersweet complexity. Despite myself, I can even see its beauty.

~~

Almost two years pass before I make my third and last trip to CAFI on a sunny Friday in the early spring of 2024.

As soon as I arrive at Paul’s house, the passing of time is evident from the presence of scores of new lamps. To accommodate their proliferation, Paul has had to put up additional shelves at the top of the staircase and behind the dark leather sofa in the lounge; a coffee table is covered with tools and pieces of scrap metal. “Part of the problem,” he says with a wry smile, “is I’m not very good at selling them.”

Back in Landré’s home, Clark surveys the growing collection of objects waiting to be transformed into sculptures and lamps. Photo: Christopher Clark.

Paul and I briefly run over some of the other things that have changed since I last visited: He’s now officially a pensioner; his second daughter is living with a new partner and moved out of CAFI; a few childhood friends from the camp have recently passed on.

Paul shrugs his shoulders. “We are disappearing,” he says.

The French state does not collect data on ethnicity, but Paul estimates that the repatriate population now makes up “no more than 30%” of the approximately 300 present-day CAFI residents.

“That’s just how it is,” he says. “Eventually, it’ll just become another neighborhood of Sainte-Livrade. But I think there will always be an imprint. For me, that’s not really anything to do with the old buildings; it’s not about the memorials. It’s the life, it’s about a certain way of being. That’s what really matters.”

After saying goodbye, I head over to Paul’s bench for a brief respite before the long drive home, still turning his words over in my head. I sit and take in the view of the old camp, the long barracks extending down toward the river’s edge. On one of the warped wooden doors, a sign reads: “Danger: no public access.” Save for a lone kitten, who watches me inquisitively from a cracked concrete stoop, there is no one around but me.

I hover there uneasily for a while, between old and new worlds, not sure there is reason for me to stay any longer, yet not quite ready to leave.

Children attending school at CAFI. When they arrived at the camp, the children outnumbered the adults. Whether they moved or stayed, CAFI remained as a place of memory. Photo: Courtesy of Christopher Clark.

Christopher Clark

Christopher Clark is a journalist, filmmaker, and author who covers underreported social issues. He’s currently based in the south of France.