Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

One day, the old farmer began to draw. Grasping a pen, his hands rough and sun-weathered, he made stick figures, rudimentary scenes, on the surface nothing special. Kyong Jae Im (formerly Gyeongjae Im)* drew compulsively, obsessively, the pictures flowing from him, telling stories, representing memories. Alone in a darkened room of his Jeju Island farmhouse, he drew from early morning until well into the night, only to begin anew the following day.

“My childhood” was all he’d say to his concerned family before sending them away again. His sons and daughters, now grown with families of their own, were as confused as they were worried.

For 60 years, their father had remained silent about his past.

~~

On beautiful Jeju Island, South Korea, memories of a suppressed past are starting to come to light. Photo: Ping Han / Alamy.

It’s dawn, and I’ve set out on a hike along the stunning southwest coast of South Korea’s Jeju Island, a 45-mile-wide oval 50 miles from the mainland. Herds of ponies fill pastures in the foothills while stone, mushroom-shaped “grandfather” sculptures guard the land. Bottlenose dolphins and the island’s famed haenyeo, or traditional free-diving women, dot the sea.

A rainbow of wooden Buddhist temples arc across the surrounding hillsides, and multicolored ribbons hang from sacred trees, the stone altars of shamanic shrines tucked beneath. Cherry and canola blossoms dress the island in pink and gold. It’s April, a glorious time for a trek.

Yet there’s a somber mood in the air: It’s the island’s annual month of mourning. Many of these trails weave among sites relevant to the violence and trauma of long ago. Along the path I’ve selected, I soon note markers for a mass grave discovered some years back. I walk communally with the dead for a while in a shroud of silent contemplation.

Even in my respectful reverence, though, I recognize the profound dangers of silence here.

~~

“The soldiers came, with their torches and their guns and their cries of ‘Reds!’” — and the village was erased.

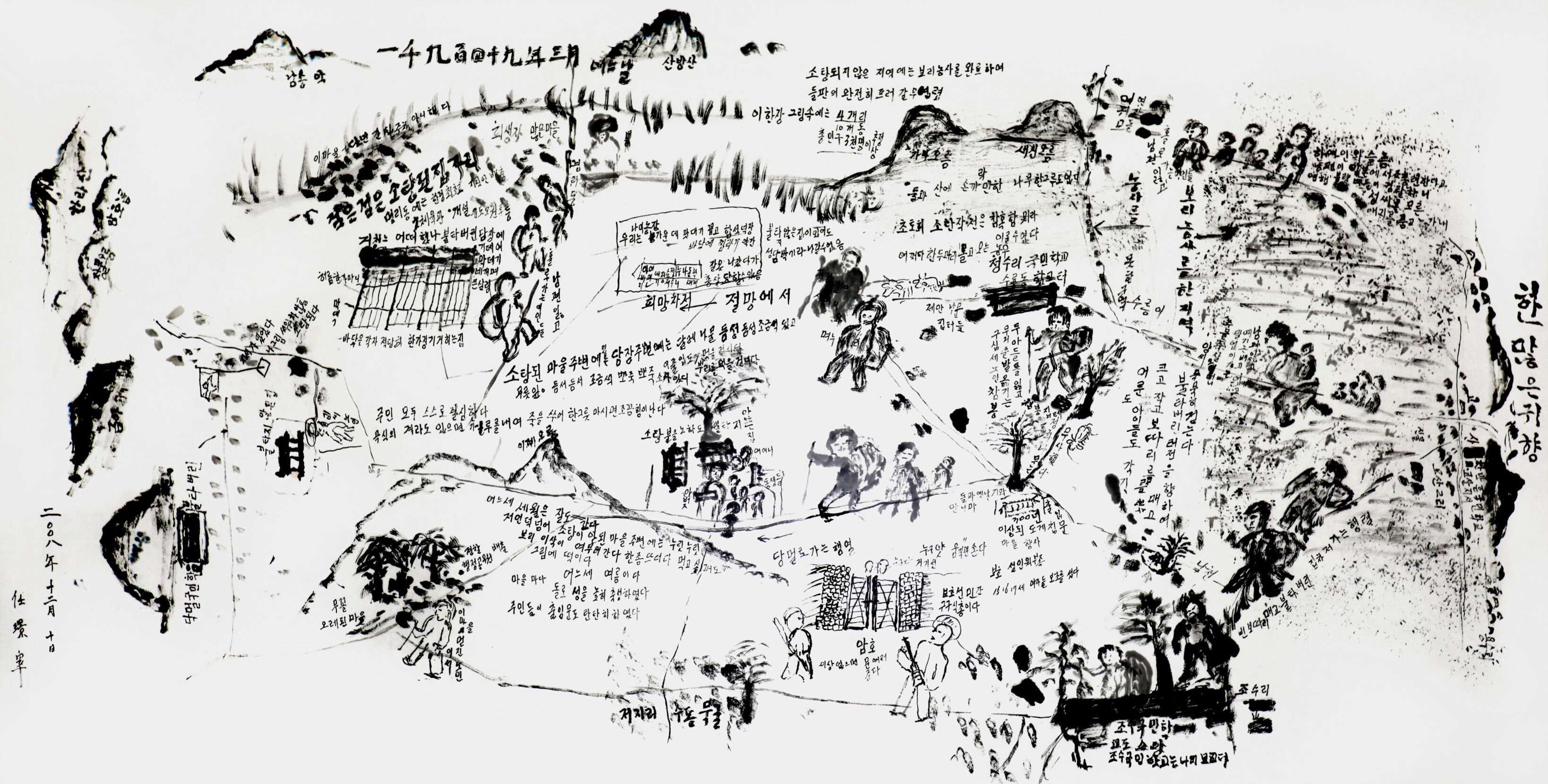

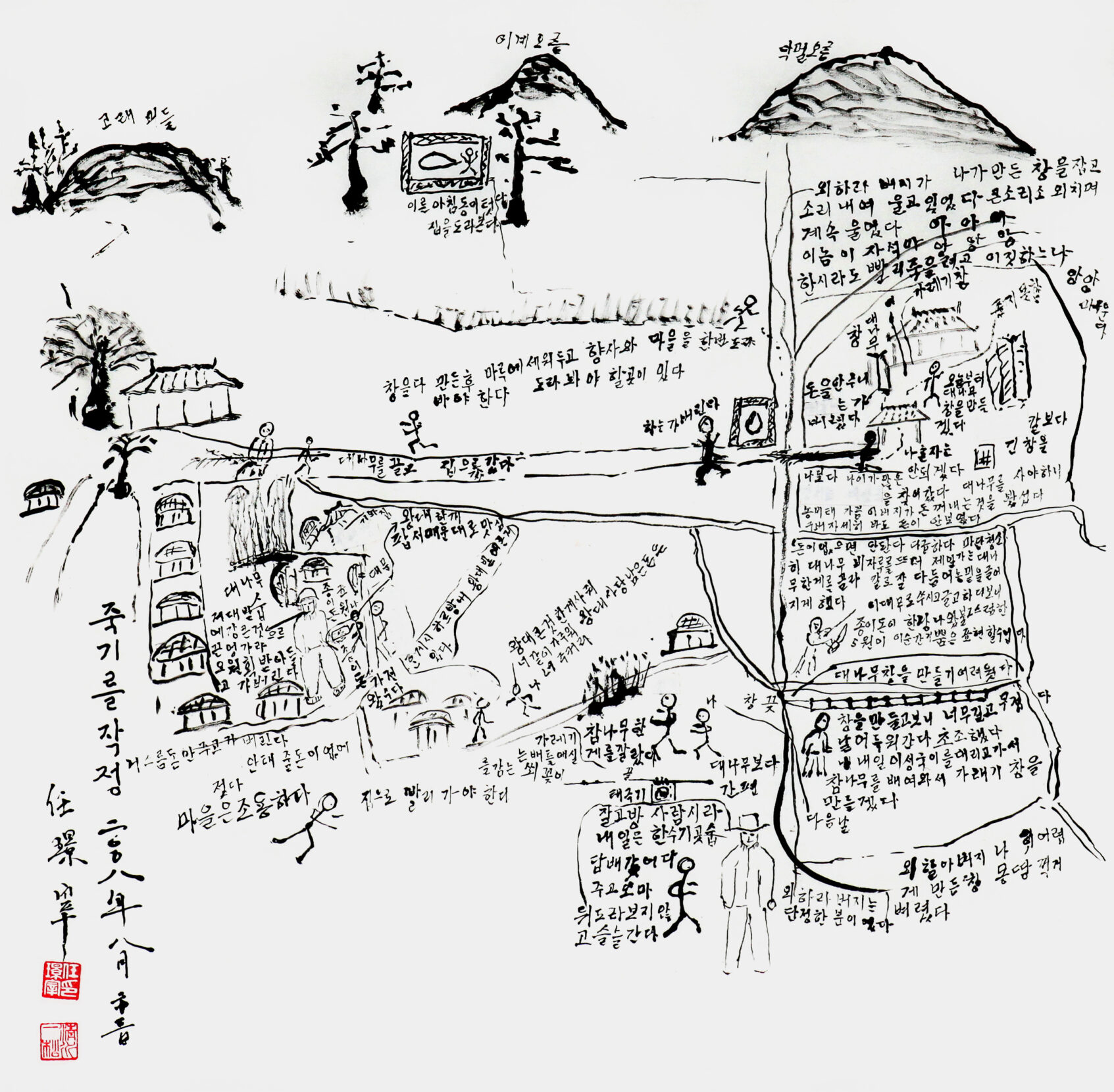

As weeks passed, Farmer Im’s drawing, tentative at first, became increasingly bold. He began to add color and captions. The images grew uglier, violent. Police officers using sticks to beat villagers. Burning houses, whole villages aflame. Young men corralled, guarded by soldiers with guns drawn — execution by firing squad.

Now that he had begun, the telling of this tale was beyond his control.

Kyong Jae Im’s compulsive drawings show scenes of villages and hills dotted with human figures and Korean captions. Once the farmer began to draw, his memories spilled onto page after page. Drawing: Kyong Jae Im, reprinted courtesy of Dr. Aeduck Im.

~~

I begin ascending one of Jeju’s 368 oreum, or parasitic cones — offshoots of Mount Hallasan, the shield volcano at the island’s heart. In Jeju mythology, Hallasan is the embodiment of Goddess Seolmundae, the island’s creator.

From the hill’s peak, I gaze down on the villages below. Low stone walls of black basalt edge tiny fields alongside stone houses, often with grave mounds nearby.

In the distance I can just make out the ruins of a Japanese air hangar.

A psychologist with a research interest in trauma, I have come to South Korea to understand better the effects of the country’s devastating 20th century. Residing initially in Seoul, I soon learn of the uniquely tragic period of state-sanctioned terror experienced on Jeju Island, located off the peninsula’s southern tip.

I relocate to the island and will ultimately live here for five years. I tell local friends that I might stay forever.

As I become immersed in Jeju life, I begin to recognize the effects of repressed trauma in its people: hypervigilance, inability to feel safe, distrust, depression, addiction, ruptured social bonds, and a breakdown of community. Hopelessness.

Five decades of silence proceeded the violence, when the truth was suppressed — by a series of dictators, a draconian national security law, deep-seated prejudice that exists to this day, and the people themselves who couldn’t bear to face their pain.

But amid all this darkness, I am curious what glimmers of light might be out there, too. Shamanism has existed in Korea for millennia, inherited from Siberia to the north, and is still actively practiced despite the nation’s ultra-modernization.

Having studied myriad iterations of this magico-religious tradition across six continents, I have the feeling that there is more to Jeju Island than meets the eye.

~~

Entering the profound darkness of the island’s gotjawal — its primal volcanic forest of black basalt, gnarly trees, and thick undergrowth — I am engulfed by the otherworldliness of its ghostly light and oddly shaped topography. I feel both unnerved and awed. Once a place for making charcoal, firing pottery, harvesting herbs — and hiding from would-be attackers — the gotjawal is sacred to Jeju people.

Closing my eyes, I conjure this place in the late 1940s. World War II and Japan’s 35-year occupation of this land have just ended. The country is divided, with two opposing foreign militaries — the United States and the Soviet Union — now on-site.

As the Cold War brews, the Korean military targets Jeju as communist, claiming the island’s small farming and fishing villages are rife with North Korean sympathizers — an accusation never proven and strongly contested. Nevertheless, on April 3, 1948 — a day forever after known as “4.3” — the island erupts in violence.

Soldiers arrive, joining local police in a search for “rebels.” The very forces charged with citizens’ safety begin hunting villagers instead.

In the late 1940s, Jeju Island entered a tragic era of state-sanctioned terror. Then, for more than five decades, speaking the truth of that time was criminal. Author Anne Hilty contemplates both the trauma and the silence as she explores around Mount Hallasan (pictured here in thick fog). Photo: Niyazz / Alamy

~~

“All that remains is the god-tree,” a poet in his 50s, tall and wiry with long gray hair, says. “Standing in the center of the village, its role was to protect its people, who regularly prayed and left offerings at its base.”

Sitting beneath a large zelkova tree, somewhere in the foothills of Mount Hallasan, I am part of a group of roughly 30 writers — academics, journalists, novelists, poets — spanning gender and age, all Jeju natives apart from this foreigner.

According to animistic custom, a central tree — within a shrine, or in the middle of a village — serves as a conduit between the worlds of human and spirit. This zelkova, ancient and majestic, has itself been deified.

“But in the end,” our guide goes on, “the soldiers came, with their torches and their guns and their cries of ‘Reds!’ — and the village was erased, with only the god-tree left standing.”

Here in the quiet of an empty meadow, the bones of the village lie somewhere beneath the zelkova’s roots.

~~

On January 17, 1949, soldiers forced approximately a thousand villagers to the grounds of an elementary school, where 299 were dragged away and executed as the village around them burned. It was the island’s single most devastating event.

Some stories from this era are only now being told, 75 years later, because they were legally suppressed for several decades under the guise of national security. The presence of communist or North Korean sympathizers on Jeju — suspected because of the island’s refusal to participate in what it saw as a one-sided election at the time of the country’s division — has never been established. Even so, the National Security Act, effected in 1948 and strictly enforced for more than five decades, prohibited citizens from any form of criticism or even open acknowledgement of the island’s government-sanctioned military violence.

To speak or write of these events was deemed seditious — a highly dangerous matter of treason punishable by imprisonment.

In the seaside village of Bukchon, on Jeju’s northern shore, a small memorial hall now recounts the chilling details of that January massacre. Graves are scattered across land that was once strewn with bodies.

As I walk the grounds, I am struck by a memorial stone to an unknown child. The pain here is palpable — for the lives cut so short, for the deafening silence of their stories.

My heart heavy, I also think of the survivors of that day and of the unspeakable horrors they endured. How could they — how could anyone — bear the weight of so much violation and loss?

~~

Amid all this darkness, I am curious what glimmers of light might be out there, too.

They look like cormorants, I think to myself, watching Jeju’s traditional free-diving women, haenyeo, from the shore.

In their black wetsuits, these women appear as graceful and as determined as those diving birds inevitably nearby. Many are in their advanced years and either lived through the 4.3 violence or were born soon after, raised in the shadow of trauma. In the water, though, they are utterly at ease.

The haenyeo pop up out of the sea, sing-whistling their sumbisori and tossing their catch into a small net dangling from a bright orange flotation ball (once it would have been a gourd). Then they dive under once more.

“When it’s a good day, and the catch is in sight, my mind is completely empty except for my goal,” Kyungja Hong shares with me on one occasion. At 62, she was chief of her haenyeo collective and had been diving for 50 years.

“And when I emerge from the water, all of my worries and cares have somehow disappeared.”

~~

After three months and multiple pages, Farmer Im finally laid down his pen. His story was now told, his catharsis complete. Walking wearily to his bed, perhaps he took comfort in the fact that, in the morning, he could return to his typical farming routines.

That night, he suffered a major stroke.

~~

“Koreans all suffer from han,” my friend and feminist leader Okhee Park, in her 60s, tells me.

We’re chatting over coffee in her sleek gallery in Paju’s Heyri Art Village, an intentional art-oriented eco-community surrounded by nature. An hour northwest of Seoul, it is nestled up to the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), the military-patrolled border between the Koreas. A poignant cemetery for North Koreans, caught on the south side of the border and never to return home, is situated nearby.

Considered a uniquely Korean syndrome, I learn that han represents a complexity of longstanding sorrow, anger, resentment, grief, and regret, the result of perceived injustice.

Perhaps ironically, han is also often used to indicate “Korean.”

“We carry so much han to this day, because of all our suffering and our still broken country,” Park explains. “It doesn’t only affect our parents and grandparents who lived through that time; we daughters and sons carry this weight in our hearts, too.”

Entrenched trauma response or post-traumatic disorder often manifests as depression, anxiety, or addiction, all of which can be inherited biologically and in the way that the affliction affects family dynamics.

With state violence, trauma is experienced individually as well as collectively. Akin to child abuse by a parent, the victim’s core sense of security is shattered. By suppressing the healing process, the trauma response instead festers and is highly prone to being passed down through generations.

Many of the locals I met spoke of feeling unsafe, or of not being able to see a bright future for themselves. “Don’t tell anyone where you live,” one 60-year-old Jeju historian told me. “It’s better if no one knows.”

In a 2020 study by Young-eun Jung and Moon-doo Kim, which included more than 1,000 survivors and immediate family members of Jeju victims, the depression rate was 24.3%, PTSD 3%, with 10.8% co-diagnosed and twice as likely to have a higher risk of suicide. This, more than 70 years after the period of violence.

“We don’t have a word for ‘healing’ of the mind,” says my friend Jeyon Kim, a Jeju native working in the island’s government. Jeyon’s own mother was widowed during this period of violence — her first husband, and the father to Jeyon’s elder siblings, among the executed. “We don’t really understand it.”

~~

Members of Jeju Island’s haenyeo, or traditional free-diving women, preserve a practice of the past. In the aftermath of the 4.3 violence, these women also helped protect — and shape — the island’s future. Photo: Xinhua / Alamy

The more I witness the ripple effects of Jeju’s past, the more my fascination with the haenyeo grows. Despite the somber weight they carry in their hearts, in the water they are buoyant — weightless and carefree.

“If you want to understand the haenyeo,” Jeju native and fashion designer Soonja Yang had told me, “you can’t do it from the land; you must get into the sea.”

And so we do. She and I, with three other local friends, join the diving women each Saturday for five months, a preservation initiative sponsored by the local government.

I’m an abysmal diver, I quickly discover, which only deepens my respect for these women who dive to surprising depths and long breath-holds. At home in the sea, powerful regardless of age, they are highly skilled and knowledgeable about their watery environs.

Themselves among the wounded survivors of the 4.3 era of terror — some physically and/or sexually, all emotionally and psychologically — the haenyeo grieved their dead, raised orphaned children, and cared for the wounded and maimed. As they birthed and raised the next generation, those widowed formed mutual aid networks to support one another.

Though the death toll remains in dispute, local researchers report as many as 30,000 dead — one-tenth of the island’s population. Of these, 78% were male, thus leaving behind a community of widows, with countless more wounded. Among the dead were a reported 814 children under the age of ten.

In contrast, the official tally indicates that Jeju resistors killed some 180 soldiers and 140 police officers.

It was also up to the haenyeo to rebuild communities economically and emotionally. More than half of Jeju’s villages are said to have been destroyed, their surviving residents confined to displacement camps.

These women midwifed the islanders’ hope.

~~

The pain here is palpable — for the lives cut so short, for the deafening silence of their stories.

A painted camellia, startlingly red, draws attention in a small, nondescript room in Jeju City.

Known for their spectacular scarlet bloom across Jeju Island each winter, these blossoms begin to fall long before their petals lose their vibrancy. The symbolism of this flower is painfully evident on this island of lost youth.

“April Exhibition” is the innocuous, yet instantly recognizable, name of this coded provocation. The year is 1988. Color and light, with just a hint of lurking evil and impending death, radiate from the abstract paintings on display.

In spite of the risks — legal, psychological, social — Jeju artists and writers had begun to give voice, however small, to their shared past. Some had lost family members. Others had been forced to flee the island.

“We’ve tried to reveal this truth through our art,” Yobae Kang and Gilchun Koh, longtime leaders in the 4.3-focused Tamna Artists Group, tell me. As we sit on a bamboo mat around a low table in Kang’s countryside art studio, drinking tea, they explain that the 1988 exhibit was the first of its kind. Later that same year, it was mounted again in Seoul, this time with more representational works that resulted in investigation by the national security forces.

Such acts of defiance had been sparked a decade earlier by writer Ki-young Hyun. In early childhood, Hyun had fled Jeju with his parents due to the rising danger. His novella, Sun-i Samch’on (“Auntie Suni”), follows the odd behavior of an elderly survivor of the Bukchon massacre. Following its 1978 publication, Hyun was also subject to investigation — as well as alleged torture by national security forces.

In trauma therapy, someone might be asked to draw images or write a story related to what they’ve endured, which allows repressed memories to “leak out” in a safe and manageable trickle. Viewed like this from a distance, in a carefully controlled manner, the trauma remains in the past, while the survivor stays safe in the present.

Emotional flooding, the sudden release of emotion so long denied, can be a danger — especially in the absence of professional supervision, as Farmer Im experienced.

Three months after the flood of his drawings began, Farmer Im suffered a major stroke. Drawing: Kyong Jae Im, reprinted courtesy of Dr. Aeduck Im.

~~

Shaman Soonsil Suh, 51, is tall and commanding, at once professional yet compassionate. She is dressed in bright red ceremonial robes and a headdress; her jet-black hair trails down her back and flies as she spins and dances.

A trio of rescue workers kneel before her. They had retrieved a woman’s body — a haenyeo who had drowned tragically — from the shallows.

The haenyeo, I learn, are among the remaining devotees of shamanism on this “Island of 18,000 Gods” — or, as Dr. Hea-kyoung Koh has written, an island “infused with spirit.”

Jeju Islanders see spirit in every rock, wave, and tree — much like the zelkova “god-tree” I’d seen earlier. As such, the island is dotted with shrines, often tucked away somewhere invisible to all but the most immediate village residents. If you know where to look, however — in a small rock enclosure with an even smaller altar or a tree with colorful ribbons tied to its branches — you begin to glimpse these devotionals everywhere.

Deep in trance, Suh stops to pound each of the rescue workers in their mid-back as if to restart their hearts; she takes soju, the local liquor, into her mouth and blows it out over the heads of each of them in turn. Finally, she perceives their return to wholeness complete, and now, in a quiet voice and calm state, she proclaims them healed — and moves on to the next rite.

~~

A few days later, I join Suh at her home. Now dressed casually, as we relax in her living room over cups of tea she is considerably less imposing — though still exuding confidence.

“The work that I do,” she says, “is not unlike your own: I use ritual to heal the minds of the people.”

I ask her how the Jeju people could heal under such suppression for so long.

“We did our work in hidden ways,” she tells me, “risking imprisonment, holding rituals of lamentation and solace for the bereaved, healing for the wounded and maimed — and consolation for the unjust dead, to help them move on. We had to be very careful, modifying our rituals so as not to attract the attention of authorities.”

The island is dotted with shrines, often tucked away somewhere invisible.

In the absence of male family members, widows clandestinely maintained chesa, Confucian rites traditionally performed by males for male ancestors — and strictly forbidden for these victims branded as traitors.

Soonsil Suh was born a decade after the 4.3 period of terror had ended. As part of her shamanic training, she was informed in detail about the events of that time.

Suh explains that she enters a trance state in order to connect with and allow these restless spirits to temporarily possess her and use her human voice to speak to the living.

For those who died during the 4.3 period, such rites were often delayed or even impossible, the spirit unsettled as a result. Trauma of the living is seen as “soul loss” in shamanic tradition, whereby a great shock and sorrow causes part of one’s soul to go missing. The shaman, in a trance state, travels to an astral plane to locate, retrieve, and reintegrate this missing soul fragment.

The bereaved, in turn, can communicate with the deceased and help them cross over to the land of spirit.

~~

Darkness emanates from the mouth of the cave. Uncertainty, or perhaps disbelief, obscures the shock of what lies inside. Slowly, though, eyes adjust to the lack of light. The charred remains of human skeletons become visible.

The very forces charged with citizens’ safety begin hunting villagers instead.

Here at the cave on Darangshi oreum lie the dead bodies of 11 people, including three children, who had fled here after their village was destroyed by armed forces in 1948, only to be burnt alive here by those same soldiers. In 1992, researchers at last found the tomb, aided by interviews with an elderly survivor who stumbled upon the corpses as a young man.

Then-president Tae-woo Roh ordered the cave to be resealed. But the researchers had taken their finding to the press, unleashing a maelstrom of reporting by the island’s journalists in defiance of laws that still banned reporting on 4.3-related news.

A single photograph of the skeletons — “the brutal reality of what really happened” — had a “huge impact,” according to an article in the Jeju Weekly, published in 2012 to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the discovery. Outrage rippled far beyond the shores of the island. The historic tragedy could no longer be officially denied.

A year after the tomb was found, the Jeju government launched a 4.3 research committee; a national “Jeju 4.3 Special Act” was established in 2000, which led to a truth commission.

In the years since, many more mass graves have been unearthed across the island. One of the largest, exhumed from 2007 to 2009, lay beneath the runways of Jeju airport and contained the bones of nearly 400 victims.

~~

In late 2002, South Korea elected Moohyun Roh, a former human rights lawyer, as president. During the first year of his presidency, he took the podium, his face solemn, as he stood at the front of a Jeju hotel meeting room.

“I believe that the time has come for us to conclude this historic tragedy that occurred between our independence from the Japanese colonial regime and the establishment of the Republic of Korea,” he said, his words translated. “Many innocent Jeju civilians were sacrificed starting from March 1, 1947, and through the armed uprising of the Jeju chapter of the South Korean Labor Party on April 3, 1948, then to the armed conflicts and suppression operations until Sept. 21, 1954.

“As president, I accept the committee’s recommendation and hold the government responsible, and truly extend my official apology for the wrongdoings of past national authorities. I also cherish the sacrificed spirits and pray for the repose of the innocent victims.”

Despite causing controversy on the mainland and outright condemnation by the conservative opposition, the moment marked a significant milestone — the first state apology to the people of Jeju Island, more than five decades after the violence began.

~~

In 2019, the truth of Jeju Island’s past finally resounded loud and clear on an international stage. Addressing a packed forum at the United Nations headquarters in New York, an 80-year-old Jeju woman, her hair short and russet-colored, testified to the horrors she endured one dark January day when she was just nine years old. In a dark suit and dark-framed glasses, she spoke with resolve.

“Discovered by the soldiers, I was dragged out into the street, and the sky was filled with smoke as the village burned,” Wan-soon Ko recounted to the gathered dignitaries. “Bang, bang, bang, I heard gunshots, and the heads I saw were gone.”

A blunt, ultimately fatal blow to the skull of her 3-year-old brother remains an especially vivid memory of that fateful day seven decades ago when the air filled with smoke and screams, and Ko lost six family members and many neighbors.

With her testimony, she shared her burden — the burden of each of the survivors of the Bukchon Massacre and of the 4.3 era — with a global audience.

~~

He made stick figures, rudimentary scenes, on the surface nothing special.

The large two-story building is painted crimson and sunny yellow. The surrounding gardens and farmland exude a sense of serenity.

I have come to visit my friend Dr. Aeduck Im, who in 2004 founded this facility in southwest Jeju as a refuge for pregnant young women whose families have rejected them.

We walk the flower-lined grounds together, then join 20 or so of the mothers, many of them still adolescents, some pregnant and others with babies in arm, in the large and cheery dining hall. She tells me of her father, this very building on a gifted parcel of his farmland.

Director of this facility and a professor of social work with two grown sons of her own, she is daughter to Farmer Im, he who spontaneously began drawing pictures of his tortured childhood.

In her office, I examine several framed drawings and, while lacking in detail, there is no mistaking the story these painful images tell.

After his stroke, she tells me, her father recovered sufficiently to create a few more drawings, though never again at his initial frenzied pace. Aeduck had the drawings printed in book form for preservation, its title taken from one of his captions: “I would like to fly like an eagle.”

Im had found an outlet for his painful memories in simplistic, childlike drawings. It was as a child that he experienced these traumatic events, thereafter locking them away in his mind as a means of survival. It was, therefore, as a child, through a pure and simple form of expression, that he could finally look at his trauma and attempt to resolve it. Healing of old wounds is often a task of one’s senior years; art is frequently used to insulate against re-traumatization as memories resurface.

When in 2008 the Jeju 4.3 Peace Park was inaugurated, her father’s drawings were prominently displayed. At long last, his story was told.

After five decades of forced silence, Jeju Island’s residents — like Farmer Kyong Jae Im, pictured here — are finally bringing their dark past to light. Photo: courtesy of Dr. Aeduck Im.

~~

A little later, Aeduck and I drive the short distance to the family farm just outside of Chongsu village, now reduced to a few greenhouses alongside their small home. She introduces me to her elderly parents. “They’re always fighting,” she says with a laugh and tells me she thinks her mom, another survivor of the island’s trauma, drinks too much.

We find her father in one of the greenhouses, tending his plants. To this small man now in his 80s, his daughter explains why the oegugin, foreigner, has come.

“Im Seonsaengnim,” I address him respectfully, bowing in Korean manner, my eyes brimming with tears — hoping he understands that I see his pain and his courage.

Soon after, Farmer Im began a slow descent into the fog of Alzheimer’s — those memories he’d long denied now disappearing for good.

~~

“I use ritual to heal the minds of the people.”

In a cacophony of drums, cymbals, gongs, and bells, the shamans in bright, multicolored robes begin chanting, summoning the spirits to join us. Yoonsu Kim, the keun-simbang or great shaman who is leading this ritual, whirls and dances in the center, long white ribbons trailing from the ceremonial knives he holds aloft, other shamans supporting him as he becomes a conduit for the dead.

It’s April, Jeju’s month of mourning, once more. I sit enveloped in the sorrow of some 10,000 others at the Jeju 4.3 Peace Park. And I reflect on all that I have experienced in my years here. Jeju people had largely welcomed my efforts to understand and shared with me what they could; I had walked the land and dived in the sea, and I had encountered the island’s spirits during ritual.

Following a litany of speeches by politicians, the Haewon Sangsaeng Gut finally begins. This modern shamanic healing ritual was designed for this express purpose and has been performed since 2002 at massacre sites throughout the island — to heal the wounded, the dead, the bereaved, the land itself. Now, through the shaman as their channel, those unjustly killed so many years ago begin to speak, airing grievances at a life cut short, lamenting and wailing.

All in attendance — survivors and descendants, politicians and artists, researchers and journalists, and outsiders such as myself — hold our breaths collectively and wait in suspense for what these restless ghosts have to say. We listen for what we ourselves must hear, how we may contribute to healing still needed.

Amplifying their voices with our own, what was once held in silence grows ever louder — a crescendo that can no longer be denied.

On Jeju Island, the truth of a dark past breaks through — channeled through art and ritual, grief and tremendous courage. Photo: Ekim / Alamy.

*Editor’s note: This article has been updated to reflect a spelling change for Kyong Jae Im (formerly Gyeong-jae Im) that was adopted shortly after publication.

Dr. Anne Hilty

Dr. Anne Hilty is an avid writer on themes of travel, culture, and human psychology — and is living her memoirs.