Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

As I walked down a dark stairway lit by a single naked bulb, the accounts of horror and suffering reached a crescendo. There, in windowless cells narrow enough for me to touch every wall while standing in their center, unspeakable tortures occurred. People who were guilty of nothing spent their final hours in these cells, crying with pain, trembling with fear. The word “mercy” was barely still visible on one wall, scrawled in dried blood. There were only two exits from those cells: the gallows or the gas chambers. It was there in those rooms that I finally understood: Auschwitz was full of ghosts.

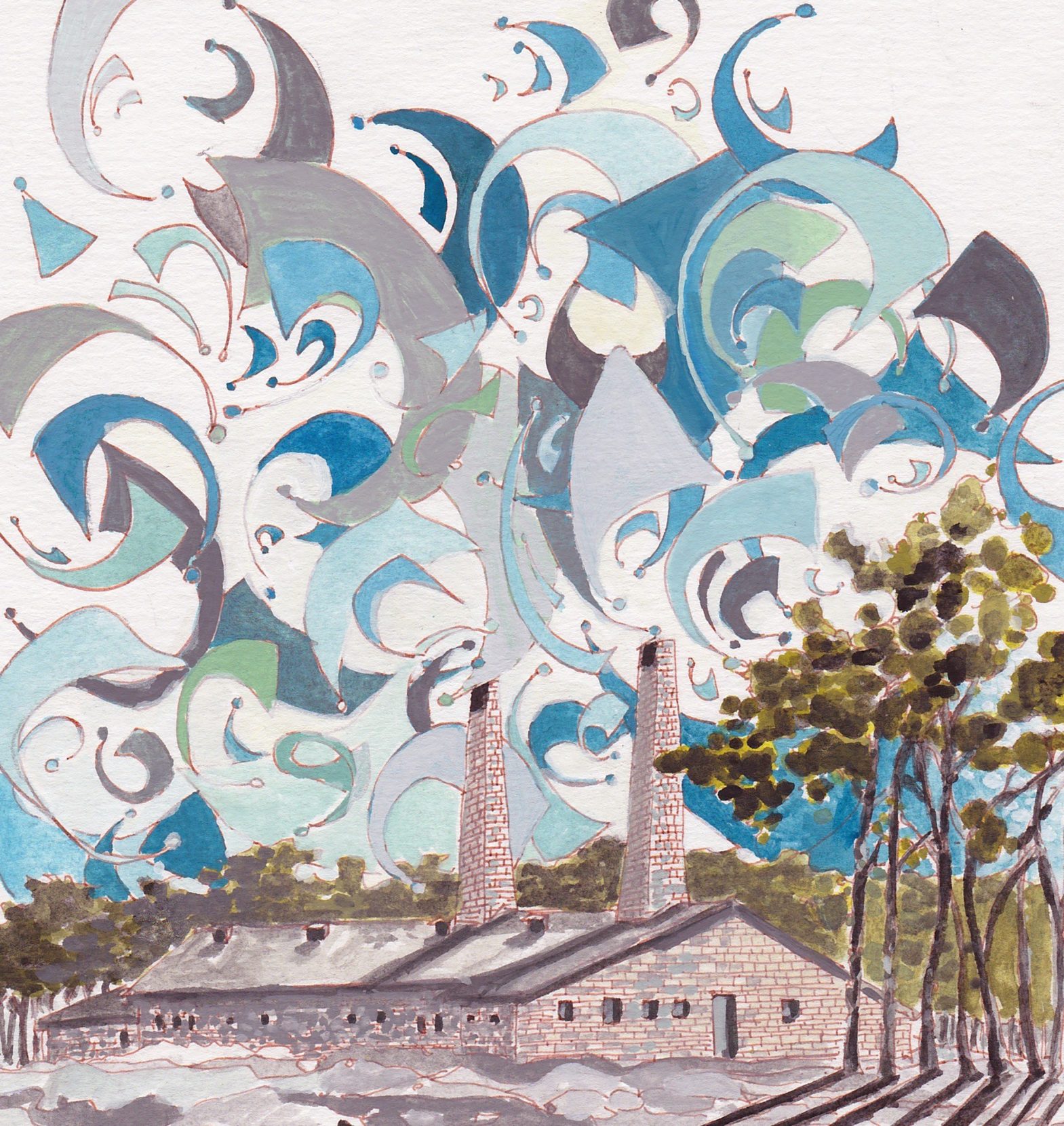

Painting by Colette Hannahan.

When I met him, Henry Leman had the melancholy air of one who had been broken. Still, he carried himself with an old world dignity. His wife, Berte, had recently died, but he still got up each morning and went through the rituals of life because he knew no other way.

His white shirts were always starched and he wore them with the sleeves rolled up and the hems tucked into black trousers. When he wore shoes, his penny loafers were immaculate, but mostly he liked to pad about in white socks.

I had delivered his mail for several months when he appeared at the door one day and invited me in for coffee, and as he spooned massive amounts of sugar into his cup, I saw the tattoo, six tiny numbers on the inside of his left forearm. I knew what they meant, but he saw me looking and quietly whispered, “Auschwitz.”

Henry Leman was a survivor of the most infamous of the Nazi death camps.

Postmen are like bartenders and priests: everyone wants to talk to them. Henry seemed lost in the cavernous silence of his home as he told me that most of his friends were gone. He had no children because his wife had been sterilized in the camp at Dachau, but somehow, the two survivors had found each other in the aftermath of World War Two and had built a life together. They had a pact not to discuss what either had gone through, but when Berte died, the ghosts came searching for Henry, and Henry came to me. I admit that the events of the era he survived and that my own father fought in — dark as they were — fascinated me. So, with that first cup of coffee we began a series of conversations that lasted until his death several months later.

This story needed to be repeated, not just now, but over and over again.

He spoke at first without emotion; “Have you ever heard someone scream from absolute total pain?” he asked.

“No,” I answered plainly.

“Pray that you never do,” he said while pouring me another coffee. “I used to dream of coffee,” he added, changing the subject, “and anything sweet, especially sugar. That’s why I can’t get enough of either now.”

Not infrequently, his stories turned into life affirming parables, the kind that a man surrounded by death would have to cling to in order to keep his sanity: a flower springing up near the gallows; a bird singing while a firing squad executed prisoners.

More often, though, he would pause to gather his thoughts in silence and then, in a hushed, monotone voice, that chilled me every time, he would say something like, “It was hardest watching the children die.”

His voice would gain power then, and he would grab my hand in a vice-like grip to emphasize a gruesome memory that had returned to him. I never understood how he could recount the stories with no trace of hatred or bitterness.

But still, the words did not come easily. He would cross and uncross his legs while squirming in his chair as though what he was saying crawled over his skin like an insect. I tried to relate to his images of pain and death that both repelled and transfixed me, but they were beyond my comprehension. I had not lived it.

“Do you believe in God?” I once asked him.

“Yes,” he said, “but God was not in Auschwitz.”

I recognized him even though he was a moving skeleton, a human shadow, broken, emaciated, and defeated.

We sat at the dining room table where he served strong black coffee in Daulton China cups with gold trim — the final remnants of a bygone era. In a cupboard on the wall there was a gold menorah and a selection of Bertes’ Hummels. Henry regularly made me late for my route, but I did not care.

He had never completely come to terms with his past and it was as if, by telling me his story, he was both purging his soul and assuring that his tale would not be lost with his passing. There was only one time I remembered watching tears form, and as one ran down his cheek, he stood and politely excused himself from the room. I quietly let myself out.

Henry was a twenty-year-old student when the Gestapo came in the night. Four days later he was greeted in Birkenau, Poland by the “Angel of Death” himself, Doctor Joseph Mengele, who immediately chose victims for his sadistic experiments while deciding life or death for everyone else on the train with a flip of his glove to one side or the other: To the left meant the work camp of Auschwitz. To the right meant the gas chambers. Henry’s name became a number tattooed on his forearm, and he was put to work with the Sondercommando, dragging bodies from the gas chambers to the crematorium.

Intellectually, I knew what happened in those camps, but hearing it from Henry made it too real, still too possible!

I filed his stories away, deep inside, knowing I would write about them one day, but wondering how I would ever find words adequate to the task.

~~

A decade later, it was finally time.

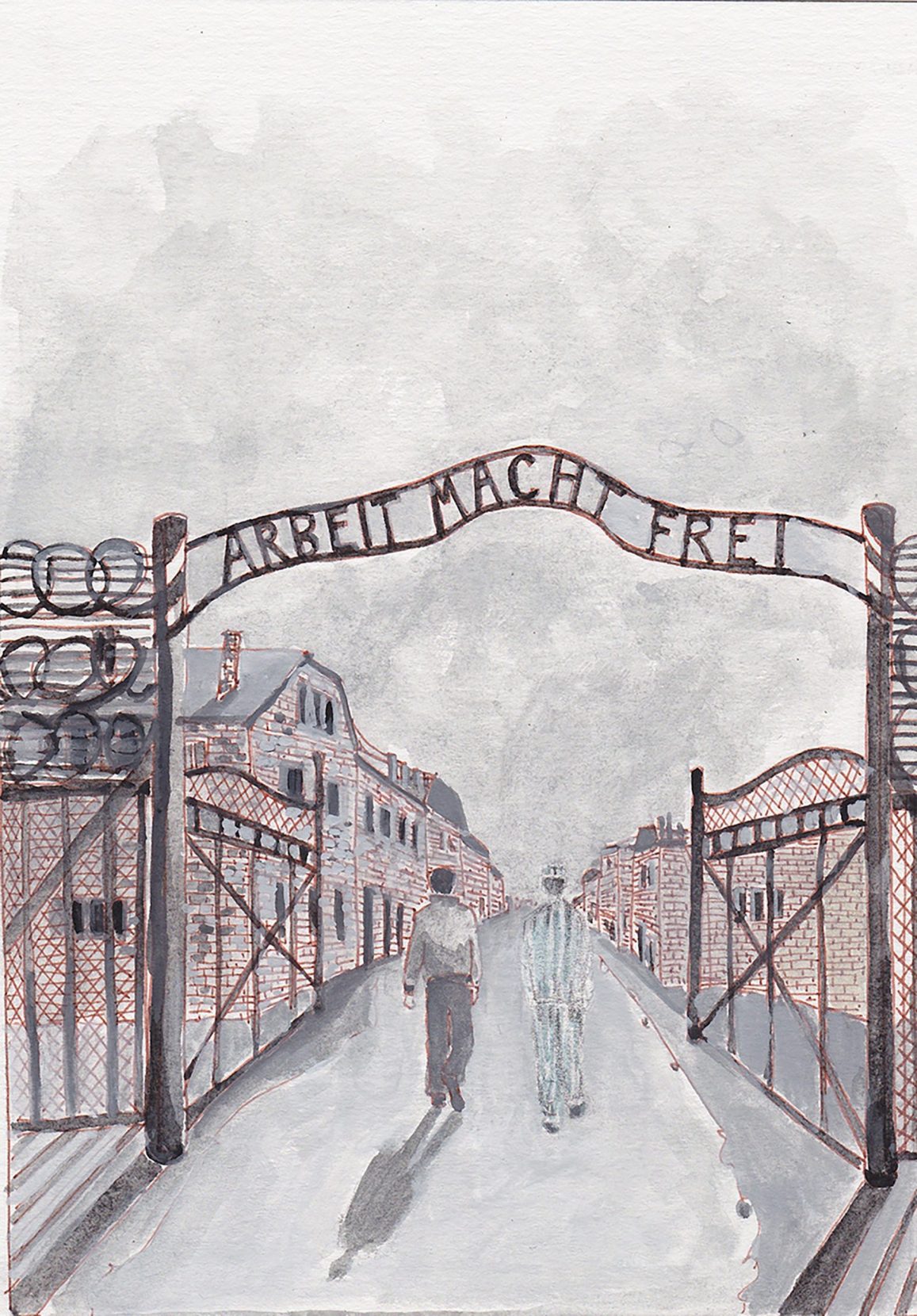

When I arrived at Auschwitz, I immediately recognized the main gate from historic photos. The curving wrought iron sign overhead read, “Work will set you free” in German. That sign welcomed the living dead to their temporary place in hell.

I stepped across that most infamous of portals and Henry’s stories came alive. I could hear the screams of pain, the pleas for mercy, the cracks of bull whips, and the snarls of fierce dogs. I could hear the unanswered prayers.

The present ceased and I felt as though I had gone back in time. I imagined Henry standing next to me in coarse blue and white striped pajamas with a pillbox hat. There was a yellow star sewn haphazardly over the left breast and his tattoo number was initialed over the pocket. His feet were wrapped in newspaper and string. He had not shaved in weeks. His eyes were as sunken and dark as his soul had become in this place. I recognized him even though he was a moving skeleton, a human shadow, broken, emaciated, and defeated. I recognized him even though he was young again.

Painting by Colette Hannahan.

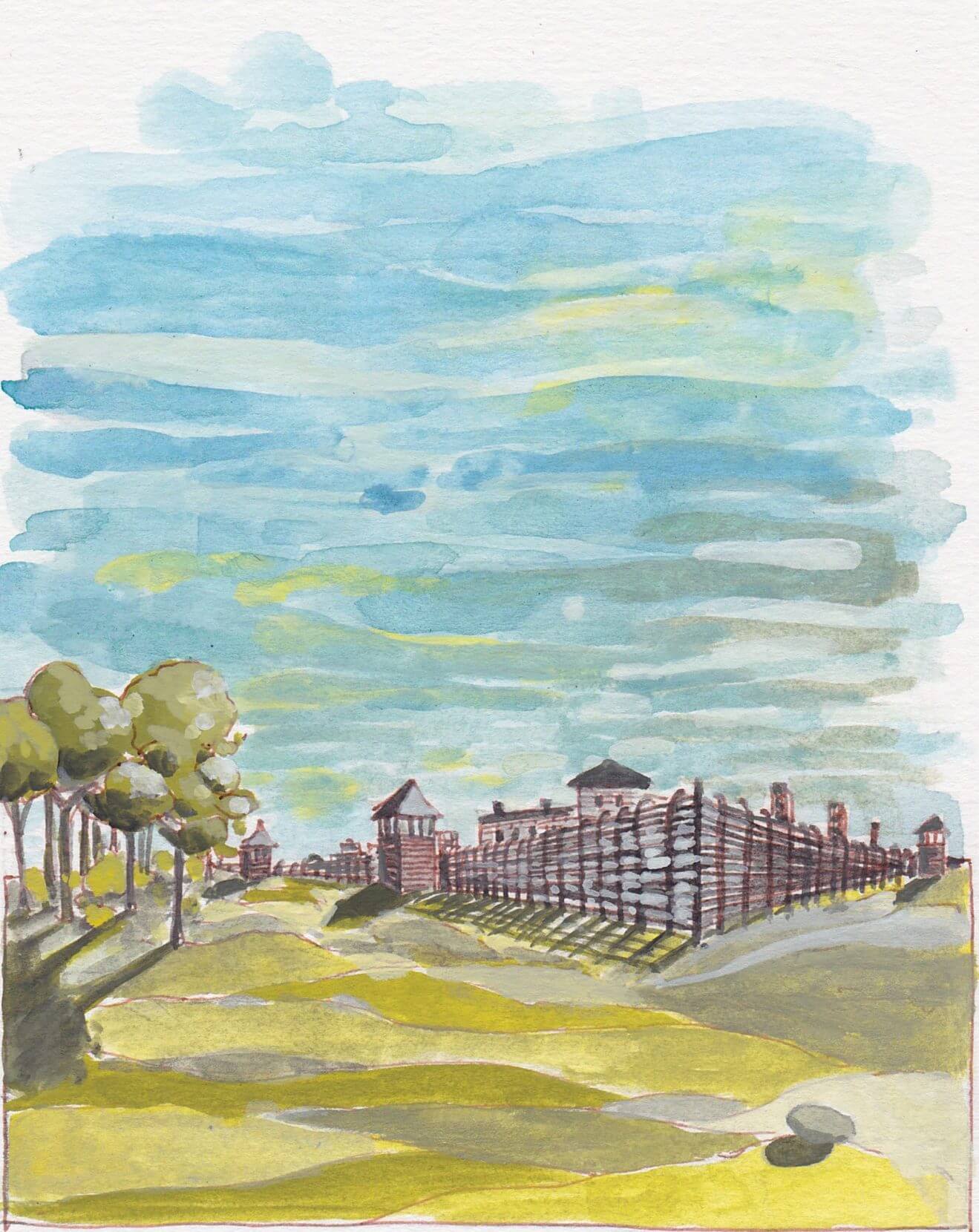

I looked left and right down the rows of barbed wire fences and at multiple guard towers that once held dogs and machine guns. Faded wooden signs warned inmates to halt ten feet from the wire or be fired upon. Henry told me the fences had been electrified and that many prisoners, unable to take the abuse any longer, had flung themselves into the fence to end their misery. At that moment, I saw sparks flying from the fence, but of course it was only in my mind. The electricity had been cut in 1945.

Henry walked by my side as we entered the first barracks, where a hundred victims had been crammed onto a cold stone floor in a room designed to hold twenty. The words of philosopher George Santayana were painted on the wall as a stark reminder, “Those who do not remember the past are doomed to repeat it.” Henry urged me along and we passed entire rooms filled with human hair, children’s shoes, people’s luggage — the accessories of daily life that had been stripped from the inmates along with their dignity. The other barracks were the same: glass-walled dioramas filled from floor to ceiling with tiny pieces of lives cut short. One room stood full of little girls’ dolls, staring vacantly, waiting for their playmates who never returned.

The collective sorrow of Europe hung like a thick fog.

It took just four years for the atrocities of Auschwitz to tear a giant hole in the consciousness of mankind. Because of that place, humanity would never be completely whole again.

I felt panicky. My breath came hard and fast and my hands began to shake. I wanted to flee, but could not. There was one last stop we had to make.

The gas chambers at Auschwitz sit low and squat, dull concrete bunkers with sod roofs, neatly framed by a beautiful forest only a few yards away — a final tease of freedom before a slow and painful death. I stopped at the massive steel door and peered through the tiny glass porthole, the same one where SS guards watched thousands asphyxiate as Cyklon B, a gas developed as an insecticide, was dropped through a ventilation shaft in the ceiling. It was a cruel death. Two-and-a half million lives were taken in that room. And that was where Henry had worked, handling bodies. I hesitated at the door and young Henry pushed me through, telling me I had to continue.

I fell into line with the ghosts filing in one by one. I stood in the middle with closed eyes and imagined the gas pellets being dropped through the ceiling vent. I felt myself choking and sucking for air, my eyes began to burn and the blood rose in my throat. No sound came from my lips but I was silently screaming. When I opened my eyes, though, I was alone in the deafening silence, standing in the dimly lit room on a floor stained black with the fluids that exit a human body upon death. They were stains that no amount of cleaning and no amount of time could erase.

I forced myself into the next room with the giant ovens whose fires consumed the mortal remains. And when I exited, Henry was waiting for me. I could never truly understand what he had gone through, but now I had the briefest glimpse into the lowest moments of human history.

Together, we walked behind the crematorium to the rotting wooden gallows where the camp commandant, SS-Obersturmbannfuhrer Rudolph Hoess had been hanged in 1947 for crimes against humanity. I felt nothing. No price was sufficient to balance the debt he owed. It was Hoess who introduced Cyklon B as an efficient killing tool, allowing the SS to murder 2,000 people per hour when the ovens were operating at full capacity. It was his own written and verbal estimates that put the death toll at Auschwitz near 3.5 million people — 2.5 million he said died in his gas chambers, while another five hundred thousand to a million died of overwork, starvation, beatings, and suicide.

When Russian soldiers entered the camp on January 27, 1945, Henry was one of 7,500 people still alive at Auschwitz. He weighed 92 pounds.

Henry’s ghost whispered in my ear that this story needed to be repeated, not just now, but over and over again, lest the prophesy of Santayana come true. And then he turned to be with his Berte and he left me for the last time.

It had been ten years since I’d first sat down to coffee with Henry Leman. I was a convenient confidant and nothing more. Of that, I am certain, but for that, I am grateful.

As I walked towards the gate to exit, I remembered an old Jewish tradition of placing a stone on a grave. This was not Henry’s final resting place, but it was close. At the very least, a part of him had died here all those years ago.

I approached the barbed wire and took a final look back. I picked up a stone from inside the gate and carried it just outside the camp. I left it there, beyond the guard towers and outside the gates and fences that had once imprisoned him.

Henry Leman was finally free.

Painting by Colette Hannahan.

James Michael Dorsey

James Michael Dorsey is an award-winning author, and explorer, who has spent decades documenting vanishing cultures in Africa and Asia.