Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

The immaculate parade of white headstones stands at attention, stretching toward the cloudless horizon, its symmetry relieved by shrubs and flowerbeds. A 15-year-old English boy — self-consciously cool in his brown corduroy jacket, his hair a lengthy mop — wanders from grave to grave, pausing here and there to inspect the inscriptions.

His mother reaches for her handkerchief — perhaps shedding a tear at her own memory of loss.

To his own surprise, in this landscape of tight formation, he is quietly humming a recent Beatles hit: “The Long and Winding Road.” He forgives his parents for temporarily extricating the family from the pleasures of their French vacation — of fresh croissants, patisseries, and sandy beaches. Any moans of protest are now forgotten as he finds himself absorbed in awe at the scale of this silent spectacle.

One inscription on a memorial at the entrance to the cemetery particularly moves him:

“When you go home, tell them of us and say,

For your tomorrow, we gave our today.”

~~

One in a batch of faded monochrome photos, undated but most likely from about 1940, shows four young soldiers. They’re wearing the kind of wide-brim Tommy tin hat that would become a cliché for the British soldier. All four are clutching pipes, perhaps expressing some private joke. Despite their uniforms, they look scruffy, boyish, and cheerful.

Basil Hase Delaney Ankerson is the shortest of the four. His training as an electrician was interrupted by the delivery of a letter on the morning of December 10, 1939, three months after war was declared on Nazi Germany and 20 years after he was born in southwest England.

I imagine him bracing himself as he closed the door behind him, first against the morning chill, then in readiness for what he knew the letter would contain.

“Just as I was leaving the house… the postman delivered my calling up paper and I am to join the 1st Royal Engineers Training Battalion at Shorncliffe camp near Folkestone on Friday,” he writes from his father’s home in the seaside town of Deal in southeast England, to his sister living near London.

The event was anticipated — all fit men between the ages of 18 and 41 were designated for eventual conscription in the British armed forces, which by the end of 1939 numbered more than 1.5 million men. Single men were called to war first. Basil’s letter does not describe disruptive apprehension or youthful excitement. He had been called up and, outwardly at least, that was that.

A quartet of young British soldiers pose with their pipes in a moment of ease, circa 1940. Second from the left is Basil Hase Delaney Ankerson, who received his letter of conscription on December 10, 1939, at age 20. Photo courtesy of Tim Bird.

~~

At 20, I am going to rock concerts and spending long, enjoyable, but largely unproductive periods in the student union bar at my college in London’s Mile End Road. It’s the 1970s. If faced with a government demand — not a choice — to join up, my own response would probably be to invent a fictional illness or disability, or to plan a method of escape.

For Basil and his young comrades, plucked uncomplainingly from their civilian lives, there are discomforts to deal with on this voyage to war, but there is still the sense that this is a bit of a lark, a sanctioned adventure. His demeanor in the photo suggests a sense of humor, maybe even a hint of mischief. In the letters he writes home, Basil is a young man leaving his country for the first time, excited and thrilled by the novelty of everything he encounters.

On his voyage to an unnamed destination, he writes of “flying fish… little ones about a foot long, black on top with white bellies, and as the ship disturbs them they come out of the water and fly away for perhaps a hundred yards before dropping in again, not high, just above the surface and rising above each wave as it comes.”

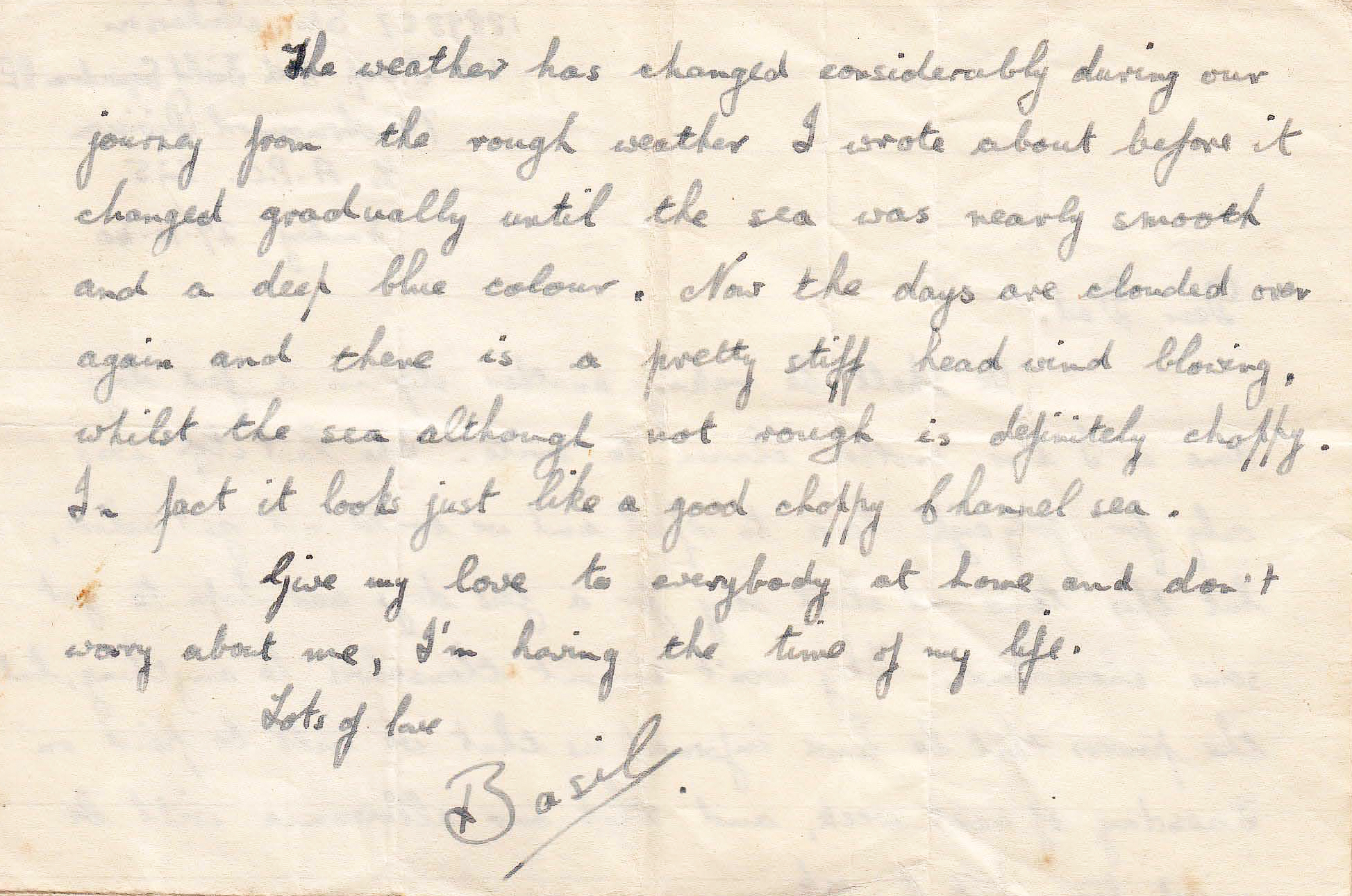

In every letter, he takes care to express reassurance to his family:

“Give my love to everybody at home and don’t worry about me, I’m having the time of my life.”

Basil Hase Delaney Ankerson — also known as Sapper B. H. D Ankerson, Royal Engineers, number 1889857 — writes to his family devotedly from places unnamed, closing this letter with a prescient phrase: “Give my love to everybody at home and don’t worry about me, I’m having the time of my life.” Photo courtesy of Tim Bird.

~~

I am six or seven years of age, sprawled on the living room floor of my family’s home on the southern coast of England. Spilled on the floor are dozens of little plastic toy soldiers, each on tiny plastic platforms, and I’m battling to stand them up in my imaginary regiments. It’s a Saturday in the early 1960s, and my father and I have recently returned from Kings toy shop on the High Street, where we have chosen another selection of green and khaki men to add to my ever-expanding miniature armies representing World War II protagonists.

Today, I place the Germans in an attacking arrow to the left and the British in a defensive cluster to the right — a miniature version of the legendary Battle of El Alamein in the Egyptian desert.

Shrill sirens flood dusty, bomb-wrecked streets as army ambulances and other urgent military traffic scurry through the haze.

I am aware that the adults in my midst lived through this war. I can name key players and am well versed in the narrative of Virtuous Allies versus a Villainous Enemy. Even so, to my young imagination, the war is wrapped in an elevated aura.

At this time, and for the next few years, I am transfixed by war films on black-and-white TV, and on the big screen. They feature British and American heroes, from The Longest Day about the Normandy landings, to Reach for the Sky about Douglas Bader, the amputee Royal Air Force pilot who flew legless. An added mystique comes from my father’s participation in World War II events in Italy and North Africa.

My siblings and I sometimes inspect his military medals, which are kept in a box with other wartime paraphernalia, including an illustrated guide to German weaponry and propaganda leaflets. The weighty medals with their colorful ribbons suggest to us some unspecified heroism but were, in fact, presented to all campaign participants. He is reluctant to recount his wartime experiences in much detail.

My mother, on the other hand, makes no secret of the single incident that has affected her most profoundly.

~~

A continent away from the Blitz — Nazi Germany’s eight-month onslaught of British towns and cities beginning in 1940 — a tempest of violence swept into Northern Africa.

With colonial power dictating the geophysical status quo, Britain retained control of Egypt, while Fascist Italy ruled Libya.

As the bombs began to fall on London that September, Benito Mussolini set his sights on Egypt and ordered an advance into the Western Desert — an exceedingly harsh expanse of sand, known for its searing heat, stretching west from the Nile.

There, the British Army had one-tenth the force of Italy: a scant 50,000 British troops against 500,000 Italian troops. The British stationed there had one objective above all else: to maintain control of the Suez Canal, the crucial shipping route between East and West that passes through Egypt, connecting the Red Sea with the Mediterranean.

Losing the Suez Canal would have had calamitous consequences, both for the British Empire and for the Allies’ chance of victory.

~~

Now accredited as Sapper B. H. D Ankerson, Royal Engineers, number 1889857, Basil writes to his father from a refueling port of call on a voyage to an unnamed war zone, ten months after receiving his call-up papers. “The troop serg gave us a very interesting talk on the town and surrounding country about the different peoples and their customs, and it has fired my imagination to such an extent that I am itching to get ashore and see things for myself.”

The place, he writes, is “a real outpost of Empire.” High, steep hills loom over a bay, leaving him in awe of “the reds and whites of the town showing up in startling vividness against the dark green hills and outside the town little white houses dotted about the hillside.”

I imagine him crouched in a corner of his quarters or lying on a bunk, scribbling his impressions. Look at Sapper Ankerson, always taking notes, always finding a time and place to write his letters home, always scrabbling for a pen and paper. He blocks out the teasing of his comrades, urgently recording his observations.

“I have still not reached the end of the journey but since we are putting into port in a few days time I have a chance to send off a few letters,” he continues, with the air of a young man on vacation.

All fit men between the ages of 18 and 41 were designated for eventual conscription in the British armed forces, which by the end of 1939 numbered more than 1.5 million men.

“I can’t say where I am or where I’m bound, of course, but I can tell you the weather is not at all the sort that I’m used to at this time of the year. The sun is very hot, so hot that they have rigged up a big awning over part of the deck.”

~~

On a cloudless spring morning in 2023, I emerge with my wife from a clanking vintage hotel elevator and into the streets of Alexandria, Egypt. It is Ramadan, and in my notebook that evening, I scribble about trams that rattle through the streets and the amplified mullahs’ calls to prayer that ring through the air from the minarets. I describe art deco hotels and apartment blocks, glimpses of harbor views, and the broad curve of the “corniche” promenade.

We stroll along the promenade, cooled by a fishy breeze, passing bobbing boats and skate-boarding lads who pause to grin for my camera. Girls in hijabs giggle at my wife’s uncovered auburn hair, crowding around her and gesturing at me to take a photograph, ushering her to the center of their group. She obliges, laughing, and I take the photo. They ask her where she’s from, but it isn’t clear if they recognize the name of the country — Finland — when she tells them.

As darkness falls, strings of colored lights illuminate the mosques, and lines of hungry fasters start to form outside the cafes and restaurants.

Horse-carriage taxi drivers shout out to me, but apart from the hell-bent, honking traffic, there is less hustle and hassle and less sticky heat than we were warned to expect. Even so, we’re a little frazzled. The city’s frenetic energy is out of sorts with the Nordic order to which I am now accustomed.

~~

“I’ll bet you’re having the time of your life stationed in England,” Basil writes to his sister, now 19, upon her own conscription to the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), the non-combative women’s wing of the British Army. “Nice clean clothes and water on tap, in fact all the comforts of home…”

It’s April 1942 — more than two years into his service and no leave possible for at least another two. Basil’s novelty of adventure may have hardened into a battle-wrought pragmatism, but his sense of humor remains intact. Belonging to the 7th Armoured Brigade of the British Eighth Army, he writes of his pride at being a “Desert Rat,” as its soldiers are known. I imagine his sister smiling as she reads.

“You ought to see the pair [of trousers] I’m wearing now. I left my good suit of khaki in stores because I knew that we would soon be wearing shorts etc and the old pair of slacks I brought up are so thick with a mixture of sand, grease and engine oil that when I take them off I just stand them up, and then in the morning I take a run and jump straight in them.”

~~

In Alexandria, I follow the promenade, dodging the uncompromising traffic, to Fort Qaitbey, watching the Mediterranean surf crashing against the pier at the harbor entrance. A vendor calls after me, but I decline his offer of souvenir seashells. Fishermen are mending their boats and nets in the harbor.

Parts of the fort were constructed with remnants of the ancient Pharos — the lighthouse listed as one of the Seven Wonders of the World, wrecked by a 14th-century earthquake. Later we visit the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, the high-tech, gleaming version of the ancient library destroyed by fire in 48 BC by Julius Caesar’s Roman fleet.

I think about how the city is no stranger to trauma, some of it inflicted by natural disasters, some by uninvited foreign incursions. Founded in 332 or 331 BCE by Alexander the Great, it was buffeted between religions, and passed from Rome to Persia to Britain.

We have come here to the country’s second city — neglecting the pyramids, Red Sea beaches, and coral reefs — because of one of those historic incursions that has long occupied my imagination.

As I head away from the promenade to explore the backstreets, a sand-blown khaki image forms in my mind. Shrill sirens flood dusty, bomb-wrecked streets as army ambulances and other urgent military traffic scurry through the haze. I hear dull, explosive thuds and see black smoke blooming overhead and on the horizon.

~~

During the preparatory stages of the Battles of El Alamein, a South African sapper lays a Mark II anti-tank mine in the Western Desert. Photo: Imperial War Museum (E12778).

In the summer of 1942, war rumbles louder and closer to Basil. A shadowy photograph dated June of that year shows a soldier in shorts carefully placing an anti-tank mine into a shallow hole in the Western Desert. His back to the camera, the soldier is unnamed, identified only as a South African sapper in the archives of the Imperial War Museums in London.

It’s unlikely that Basil has ever met this comrade in arms, but circumstances could easily place him just out of frame, engaged in a similar task. While the generals devise their strategies and the troops prepare for battle, sappers prepare the infrastructure of war — clearing mines laid by the enemy and placing their own, building temporary ramps and bridges, and maintaining vehicles and hardware.

By now, British troops are substantially augmented by soldiers from British Commonwealth countries, including India and Australia, with Germany fighting alongside Italy. In any given month, which side holds the advantage plays out in a seesaw of advances and retreats, captures and defeats. In June 1942, Axis troops take a lead, having destroyed most of the British tank force to reclaim the Libyan port of Tobruk. On June 30, the Axis forces push into Egypt and reach the British defenses at the relatively insignificant location of El Alamein, some 75 miles west of Alexandria along the Mediterranean coast. A grinding battle ensues.

This is what Basil and his comrades have trained for, but I imagine the bravado in his letters transforming into fearful anticipation. Suddenly his mechanical tasks assume an unprecedented urgency. We can only guess if the participants on both sides grasp the significance of their actions or the full extent of their peril.

~~

“It has fired my imagination to such an extent that I am itching to get ashore and see things for myself.”

“We’re so glad that you made this journey,” says Mai Abouzhara, ebullient and brisk, dressed in businesslike Western style, and fluent in effusive English. We have arrived at a walled enclave of calm in the midst of urban chaos. Mai is the regional representative of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Mai has driven us to Alexandria’s Hadra Commonwealth War Grave Cemetery on this crisp spring day in late March. The cemetery is a 15-minute drive from the hotel, but we take a detour to buy flowers.

The cemetery, she explains, is one of two in the city. The other, a larger one to the west along the Mediterranean coast at El Alamein, also includes German and Italian cemeteries. The Hadra site originally contained 1,700 burials from World War I, including casualties from Australia, New Zealand, and India. World War II accounted for the graves of a further 1,305 Commonwealth combatants after the cemetery was extended in 1941.

The graves, most reflecting dazzling sunlight from immaculate white Portland stone imported from England, stand in formation. In all directions, they stretch across velvet lawns, serving as perches for the swooping hoopoe birds, their distinctive crests aptly reminiscent of some ceremonial headgear.

As we step into the cemetery, I squint against the sunlight. I recognize the familiar inscription on one of the headstones and am transported to 1970 — the teenage version of myself transfixed by that Normandy cemetery, the resting place of countless Allied casualties of the D-Day landings of June 1944.

More than half a century later, I remain touched by the melancholy couplet — by the poetic plea to future generations, by the collective confirmation of so many brutal conclusions to young potential.

“When you go home, tell them of us and say,

For your tomorrow, we gave our today.”

~~

That morning in our Alexandria hotel room, I return to the well-thumbed scans of my family’s wartime correspondence, lingering on the saddest one of all.

My mother … makes no secret of the single incident that has affected her most profoundly.

I imagine my grief-stricken grandfather sitting down to write to my mother when he receives the news he has most dreaded. My mother, smart and prim in her olive green ATS uniform and army cap, stifles a sob and dabs her eyes as she reads the news.

“Well dearest, you are a soldier now and so darling I am going to ask you to be a real one for a little while as I have just had very bad news for all of us,” my grandfather has written.

I picture Uncle Basil in July 1942. He takes the short, shaky journey in an ambulance from the desert in the west, rushed from battle to a British military field hospital in Alexandria, thuds and booms reverberating in his wilting head, the stench of sulfur in his flaring nostrils.

~~

Using the numbered plan of the cemetery, it doesn’t take me long to find Basil’s grave. I had calculated from the dates of his death and the activities recorded in his regiment’s archives that he met his end from injuries sustained in the preparatory stages of El Alamein in July 1942.

Among the set of fading black and white photos that show young Basil with his three grinning comrades is an image of a hastily assembled wooden cross in an unnamed cemetery. I now see that this has been upgraded to smart white permanence, marred only by a hairline crack in the top right corner.

It bears a brief and informative inscription: 1889857 Sapper B.H.D. Ankerson, Royal Engineers, 19th July 1942. Basil Hase Delaney Ankerson. Delaney was my grandmother’s family name; Ankerson was that of my grandfather. Hase was the family name of my grandfather’s close friend, a fatal casualty of World War I.

Until this moment, I have been preoccupied with the practicalities of getting here, of visas and late-night airport arrivals. At last, confronted with the grave and the familiar name engraved formally on stone, we linger quietly for some moments. My elation at having located the resting place of my mother’s brother is tinged with sadness at the distance, in both time and place, of its circumstances.

I never knew Basil, but I recognize in his letters a familial flair for observation. My career as a writer and photographer has allowed me to share my own adventures in many remote locations and circumstances. But these have never included participating in war or conflict. My country of birth has dispatched its soldiers, sailors, and airmen to far-flung places to engage in conflict fairly regularly during my lifetime. But those wars and their consequences have been kept, so far and as much as possible, at the national arm’s length.

My interest in what became of Basil grew stronger over the nearly two decades since the passing of my parents, based on simple curiosity as well as the wish to perform a kind of posthumous service to my mother. Although she had referred to him with fondness and affection, it seemed that she had not really known him as an adult. For her, as well as for her children, it was his letters that brought him to life.

~~

Basil’s pristine headstone poses a host of questions, none of them conclusively answered by the blunt official explanation quoted in my grieving grandfather’s letter to my mother: Battle Casualty.

“Poor Basil has passed over,” my grandfather had written to my mother. “The notification has just come through that he died in the 8th General Hospital Middle East, Battle Casualty. That is all the details I have. I had hoped and prayed so hard that he would be spared to come back to us. But for some unknown reason it was not to be.”

Had he died in pain? How did he die? Where exactly did he receive his injuries, and what exactly were they? Was he frightened, oblivious, pumped with numbing adrenaline? Was it relatively quick, or was it horribly drawn out? Was he in the company of comrades when he was injured? Who fired the final shot? Or did he actually die as the result of some terribly ironic accident, run over by a “friendly” tank in the desert, or hit by a piece of British shrapnel?

My grandfather’s message continued: “One thing we can be certain of. Basil was a good soldier. I am afraid dear I can’t write more just now as you will understand. But don’t be too upset dear as it will only make you ill.”

“A good soldier” — what does that mean exactly? That he obeyed orders? That he died in a noble cause? That he built a lot of bridges or killed a lot of Germans and Italians?

~~

On the night of October 23, 1942, the Egyptian desert erupted in a blaze of British fire that set off the pivotal Second Battle of El Alamein. Photo: No 1 Army Film & Photographic Unit/Alamy.

The first Battle of El Alamein had ended in a stalemate. But a few months later, in late October 1942, more than 1,400 guns lit up the sky in an explosive British offensive, a barrage of noise heard all the way in Alexandria. A line of sappers — Basil’s surviving servicemen — delved ahead to clear paths through the minefields.

The confrontation waged for 13 days in the Egyptian desert. By this point in the North African campaign, the numbers weighed in Britain’s favor, with nearly double the troops of the Germans and Italians.

Thousands perished on both sides during the two Battles of El Alamein, to say nothing of the countless others, like Basil, who didn’t survive the crescendo to this showdown. But the Axis ultimately suffered a defeat in what marked a turning point of the war here — the so-called line in the sand that Hitler never managed to cross.

We can only guess if the participants on both sides grasp the significance of their actions or the full extent of their peril.

A relieved Winston Churchill ordered church bells to ring out all across Britain in celebration of what he called “a glorious and decisive victory.”

~~

We rest the flowers on Basil’s grave and wander awhile among the headstones.

We thank the Egyptian gardeners who tend to the hedges, lawns, and flowerbeds. They pose a little shyly for my photographs, not expecting the attention. I take photos of Basil’s grave and the tidy white memorial queues, the sharp and life-affirming sunlight contrasting with their vast, repetitive sobriety. The cemetery is both a somber refuge and a consolation for the foolish barbarity of war, a meticulously tended and comforting assertion of dignity and remembrance.

Basil, then, the uncle I never knew and the big brother my mother lost, whose name my brother was given as a middle name, was just one of millions of uncelebrated individuals whose lives were cut short far from home.

I remember what Mai told us on the drive from the hotel. “The Commission is collecting stories of the soldiers who lost their lives in the two World Wars,” she had explained. “Each of the headstones represents a different story, of some family’s loss, of some unique and tragic event.”

As far as I know, my visit to the grave is the first by any family member in all eight decades of its existence. I have gone some way towards rescuing his profile from the silent ranks of headstones, weaving his singular identity into our family fabric. There is a satisfaction at having connected his unfulfilled future with our present.

But now, there is a new sadness. Before setting off from our hotel that morning, a message had arrived from my cousin. My Uncle Keith, Basil’s last surviving sibling, passed away in the hospital from COVID. I regret that he didn’t live quite long enough to see my photos of his brother’s grave, to hear my account, or to read this description of our visit. But there’s also a symmetry — a belated favor delivered to Basil, my mother, and grandfather, and to my surviving relatives, as well as closure, in spite of all the unanswered questions.

We zigzag through the traffic back to our hotel with its clanking elevator. We say goodbye to Mai, thanking her, and then ascend to the bar to bask in the afternoon sunshine. Looking out over the city rooftops and surf-sprayed promenade, we raise a toast to Basil.

I think of the sign-off from one of his letters, written to his anxious father in October 1940. Everything then was novel and exciting, adrenaline still flooding his veins:

“Give my love to everybody at home and don’t worry about me, I’m having the time of my life.”

Thousands of British Commonwealth headstones stand sentinel at the Hadra cemetery in Alexandria, Egypt. Among those graves is that of British Sapper B. H. D Ankerson. Photo: Tim Bird.

Tim Bird

Starting each day with the intention, not always successful in seizing it, Tim Bird is always looking for creative ways to deal with the fact that he gets bored easily.