Support Hidden Compass

We stand for journalism, science, history, and hope. Make a contribution to Hidden Compass and stand with us.

Radioactive dust has been settling in this 18-mile radius of land in Northern Ukraine for almost as many years as I have lived. Photo: Erhan Kahveci.

Iwalk through an early morning autumn mist, among vacant concrete block buildings. I cross shattered streets lined with light poles decorated with hammers crossing sickles. It’s like I’m exploring the deserted set of a post-apocalyptic film. Yet in this Soviet time capsule, everything is real.

One of the planet’s largest human-caused disasters, which eventually led to the Soviet Union’s downfall, happened here a week after I was born. While I was opening my eyes to the world, a radioactive storm was making the city of Pripyat and the settlements that surrounded it uninhabitable in what’s now known as the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.

I hear dogs barking in the distance, breaking the silence.

After more than 30 years, the abandoned places in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone are slowly crumbling like this kindergarten library. Photo: Erhan Kahveci.

The people who used to call this area of Northern Ukraine home were mostly young families. Photo Courtesy of Ivan Zholudi, Pripyat-City.Ru.

At 01:23:04 a.m. on April 26, 1986, a previously failed test began at Vladimir Ilyich Lenin Nuclear Power Plant, better known as Chernobyl, on one of its four reactors. Less than a minute later, two explosions blew off the reactor’s 1,000-ton roof, spewing out a fire of radioactive particles.

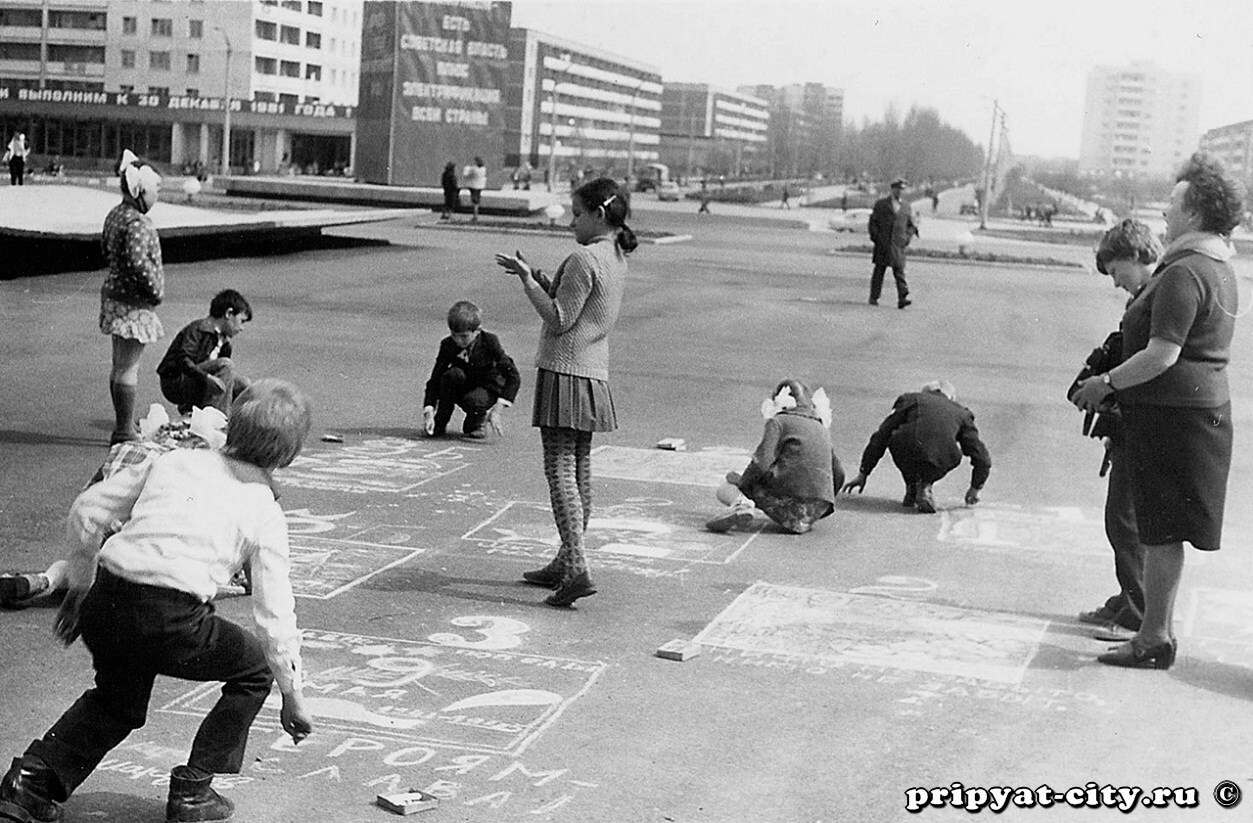

In the morning, life went on like any other spring day. Neighbors greeted each other. Parents walked their babies in strollers to parks. Children played in the streets. It wasn’t until the following afternoon that loudspeakers were driven through Pripyat and the surrounding area commanding more than 100,000 men, women, and children to temporarily evacuate their homes by convoys of buses rushed in from the capital Kyiv:

Listen to the Pripyat Evacuation Announcement

For the attention of the residents of Pripyat! The City Council informs you that due to the accident at the Chernobyl Power Station in the city of Pripyat the radioactive conditions in the vicinity are deteriorating. It is highly advisable to take your documents, some vital personal belongings, and a certain amount of food, just in case, with you. Comrades, leaving your residences temporarily please make sure you have turned off the lights, electrical equipment, and water and shut the windows. Please keep calm and orderly in the process of this short-term evacuation. — Evacuation announcement. Pripyat, USSR. 27 April 1986 14:00.

But that temporary evacuation became almost forever. What it left behind is a Soviet model city frozen in time.

Trees have taken over this former treasure of the Soviet Empire, which now stands vacant. Photo: Erhan Kahveci.

Lenin Square, in front of Pripyat’s cultural center, was a gathering place for parades and pomp and circumstance in the Soviet model city. Photo Courtesy of Alexei Perminov, Pripyat-City.Ru.

~~

Tracking devices beep all over the bus I’m riding through northern Ukraine, looking for radiation that is lurking in this 18-mile radius of land.

I arrive in Pripyat — where people witnessed the disaster first hand.

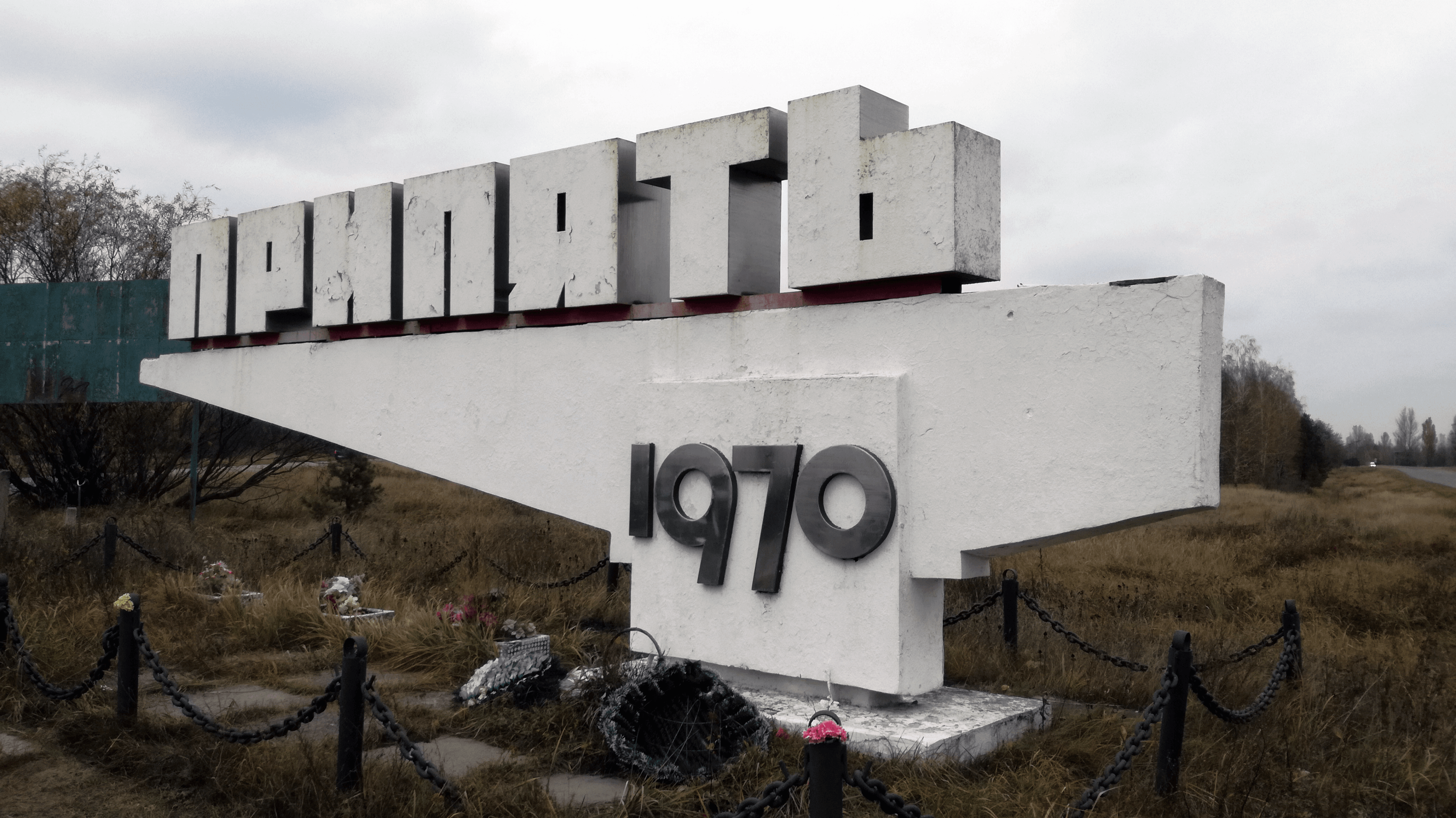

Visitors now leave flowers at Pripyat’s former city limits, as a makeshift memorial. Photo: Erhan Kahveci.

Pripyat was a Soviet model city and residents even posed for wedding photos in front of its welcoming sign. Photo Courtesy of Pripyat.com.

The city’s construction began in 1970 and nine years later, the city officially opened its doors to power plant workers and their families. The living standards for the more than 40,000 resident workers of Chernobyl were among the highest in the 15-state Republic.

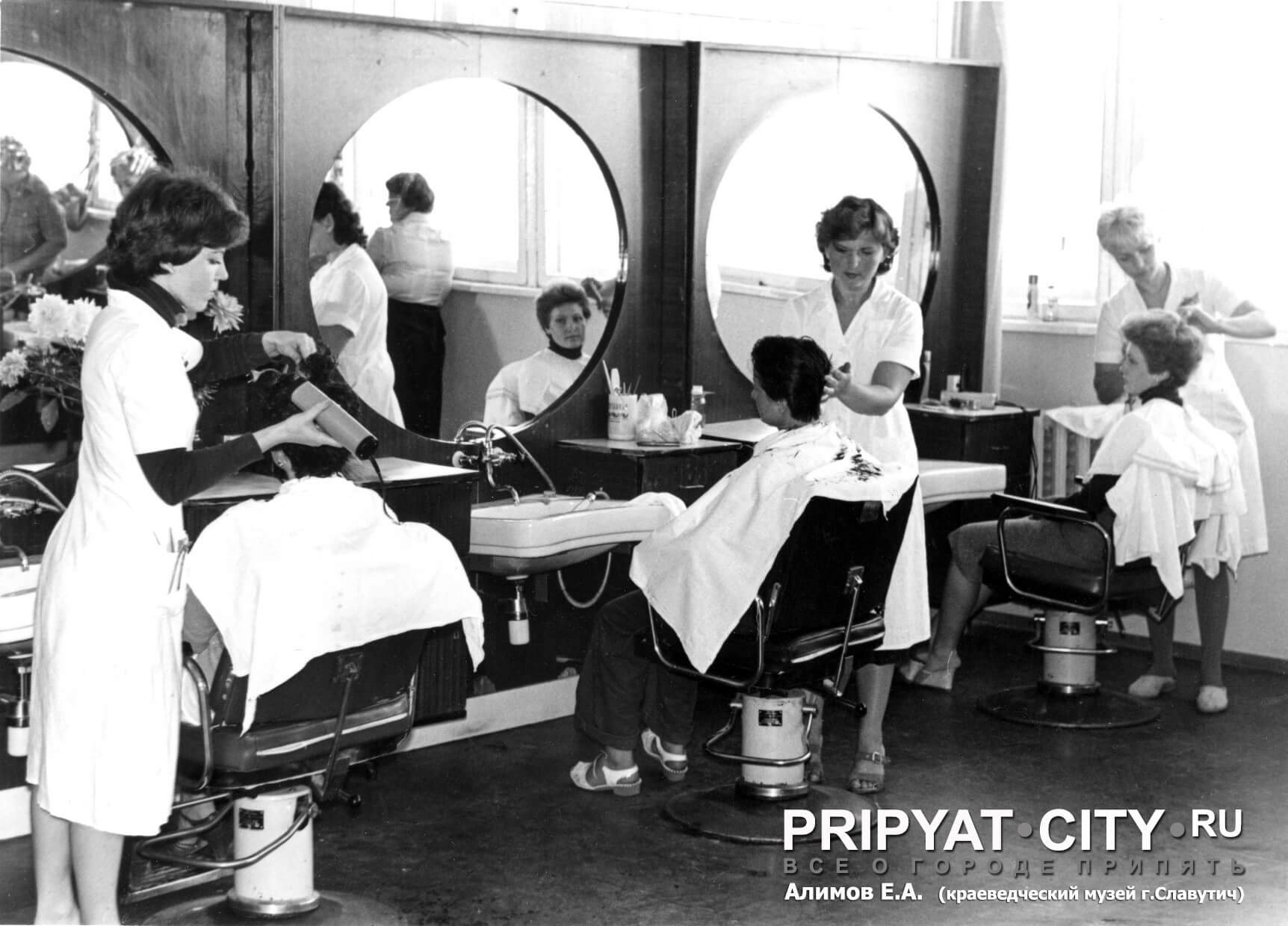

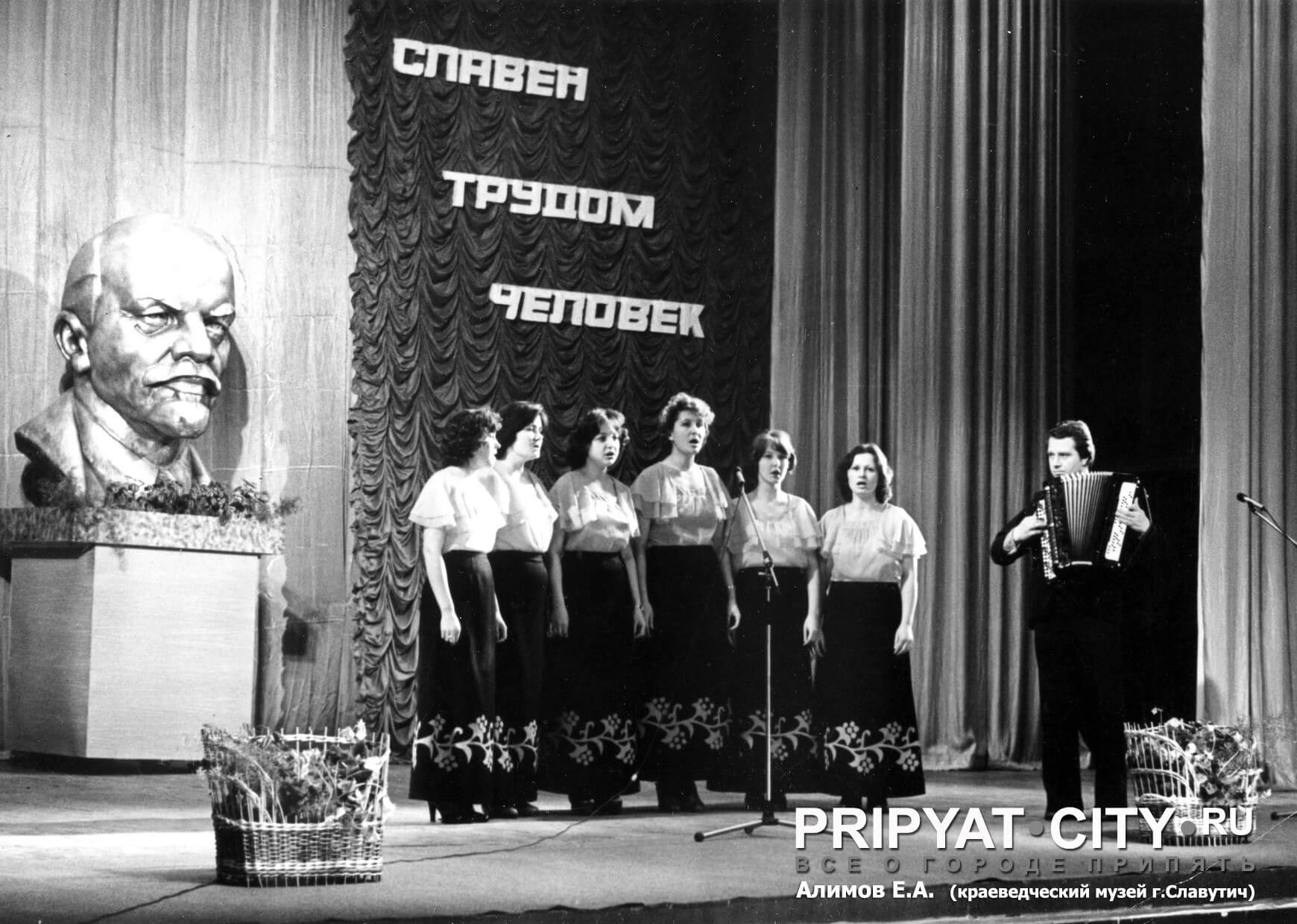

When they weren’t working, the young families, who averaged 26 years in age, spent their time at the theater, cinema, and shopping in a supermarket (which was unheard of in Soviet Ukraine).

Despite its small size, Pripyat had a higher standard of living than most other places in the USSR before the Chernobyl disaster. Photo Courtesy of Igor Egorov, Pripyat-City.Ru.

Despite living in the shadow of a nuclear plant, some of the residents of Pripyat lived a life punctuated by leisure. Photo Courtesy of Evgeny Alimov, Pripyat-City.Ru.

Pripyat was founded for the power plant workers and their families, offering them a higher standard of living than was available across most of the Union. Photo Courtesy of Evgeny Alimov, Pripyat-City.Ru.

There was even an amusement park, which was supposed to open a few days after the accident, on May Day 1986.

But the children never got to play in that park and squeal on its yellow Ferris Wheel. Pripyat, the Union’s favorite child who was given everything, died at the age of seven.

While this Ferris wheel is safe to stand next to now, there is a hotspot in one of its seats that has 1,000 times more radiation than the average for the Exclusion Zone. Photo: Erhan Kahveci.

An amusement park and stadium were constructed for the residents of Pripyat, but were never used because of the disaster evacuation. Photo Courtesy of Piotr Stepanovich Vygovsky, Pripyat-City.Ru.

~~

The grandeur of the former U.S.S.R. is now covered with rust and cobwebs.

The park was set to open in Pripyat just four days after the accident, on May Day, the biggest celebration in the Union. Photo: Erhan Kahveci.

Where children once laughed and were carefree, there is now an eerie silence. Photo Courtesy of Sergei Nekhaev, Pripyat-City.Ru. PHOTO COURTESY OF SERGEI NEKHAEV, PRIPYAT-CITY.RU

Pripyat’s cultural center, the Palace of Culture Energetik, which once welcomed lively crowds, now haunts me with its stillness, corroded doors, and handrails.

Stray dogs stroll around crumbling walls. Inside vacant supermarkets and schools, trees sprout like snowdrop flowers — omens of death.

A film of radioactive dust that once left a metallic taste in people’s mouths now covers toys, bassinets, and strewn propaganda leaflets. It’s been settling for as long as I have been alive. Although the people fled, their presence is everywhere.

When the residents of Pripyat and its surrounding settlements fled the Chernobyl disaster, they left many items behind, like this teddy bear. Photo: Erhan Kahveci.

~~

The people who stayed behind enlisted remote robots to clear away the disaster’s debris. But it didn’t take long for the radiation to break the machines, leaving the workers with no other option than to finish the chore themselves. The so-called biorobots labored in 90-second intervals, many of them dying three months later from radioactive exposure.

In the end, it took up to 800,000 people to contain the disaster.

More than 200 days later, those who survived covered deadly reactor Number 4 with a sarcophagus to dampen its radioactivity. Those unnamed heroes signed their names on the coffin to celebrate their victory over the invisible enemy.

Many of the children who grew up in Pripyat would evacuate their homes and never see them again. Photo Courtesy of S. Konstantinov, Pripyat-City.Ru.

ripyat was built to support the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant (ChNPP) which was the second largest in the world at the time. The message of Soviet pride that it represented is still visible today in the area like this mural that says: “Have you volunteered?” Photo: Erhan Kahveci.

The people of Pripyat and the surrounding area celebrated their national pride carrying signs of former Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin. Photo Courtesy of Priest Vladimir Zonn, Pripyat-City.Ru.

Even with the reactor contained, it is still not safe for humans to call this area of land home — though a remarkable handful still do. One estimate says it could take 20,000 years before this area is habitable again.

~~

I sit in silence, riding the bus out of the Exclusion Zone, staring out the window at streets and courtyards that are slowly plunging into darkness as night falls. I think about the people who once lived here and the resilience of those who stayed behind to fight the radiation. I hold the heaviness of how joy and laughter can abruptly turn into horror and silence for any of us, at any moment.

I think about the children who didn’t only abandon their toys. They left behind what it means to belong somewhere. To be home.

The children abandoned their toys, not knowing that they would never return home. Photo: Erhan Kahveci.

Erhan Kahveci

Erhan Kahveci is a Milan-based documentary photographer driven by a desire to see people and the hidden parts of the world, and capture society through his images.

Never miss a story

Subscribe for new issue alerts.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive updates from Hidden Compass regarding new issues and other ongoing promotions such as workshop opportunities. Please refer to our Privacy Policy for more information.