Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

James “Ooker” Eskridge, the mayor of Tangier Island, stands gripping a microphone, the brim of his blue ball cap pulled low. It’s 2017 and he’s attending a CNN-hosted town hall about climate change. Al Gore and moderator Anderson Cooper listen from the stage.

“Vice President Gore, Mr. Cooper,” Eskridge begins, “I’m a commercial crabber and I’ve been working the Chesapeake Bay for 50-plus years. I have a crab house business out on the water, and the water level is the same as it was when the place was built in 1970,” he continues. “I’m not a scientist but I’m a keen observer. If sea level rise is occurring, why am I not seeing signs of it?”

It’s an ironic question for a tiny island deep in the bowels of the Chesapeake, one of the fastest rising bodies of water in the world. Once one island community among many, now Tangier is one of only two inhabitable islands. The rest are marshy islets barely visible above the waterline. Some have vanished completely.

~~

Tangier is not immune to the rising waters that have drawn Chesapeake’s other islands beneath the sea. During the last 170 years, the Tangier Islands (of which only the eponymous Tangier is inhabited) have lost two-thirds of their land mass, at a rate of nearly 8.5 acres annually. According to one study, without intervention, Tangier Island will be underwater as soon as 2063.

Climate scientists are confident in their projections, but to Tangier men (as the island’s residents call themselves) what’s happened in the Bay, what is happening to the island today, is the work of erosion. Rising seas, climate change, “they just can’t get their minds around it,” says journalist Earl Swift, who spent 14 months living on Tangier for his 2018 book “Chesapeake Requiem: A Year With the Watermen of Vanishing Tangier Island.” He says: “Day to day, year to year, they don’t see it.”

Tangier is one of only two habitable islands on the Chesapeake Bay, one of the fastest rising bodies of water in the world. PHOTO: EDWIN REMSBERG/ALAMY

~~

Death and the divine are intertwined on Tangier. In front yards, side yards, and backyards of elegant island homes, hundreds of graves spanning two-and-a-half centuries sew the specter of the past into the island’s sandy soil. Or at least, what’s left of it.

This deeply religious community was a center for Methodist revival camps in the early 19th century. Today, Tangier’s population hovers around 450, down about a fifth since 2000. Almost all Tangier men are descendants of the island’s white founding families. Isolated for over two centuries, the dialect they speak here — a cross between working-class Cornwall brogue and a Virginia Tidewater timbre — exists nowhere else on the planet.

Hundreds of graves spanning two-and-a-half centuries sew the specter of the past into the island’s sandy soil. Or at least, what’s left of it.

Most men on Tangier are watermen — commercial fishermen who make a hard-earned living from the crabs and oysters that favor these waters. Besides a handful of mostly seasonal restaurants, hotels, and shops, the island has no other industry. Opportunity is so limited, especially for women, says Dr. Nina Pruitt, principal at Tangier Combined School, that “when they leave from high school and go to college, they don’t come back.”

With the exception of Swift, not many people are moving to Tangier these days either. After all, he says, “who’s gonna buy a house on a sinking island?” Tourists visit in the summer but come September, all but one of the island’s restaurants and all but one of its hotels shutter their doors against howling wind and waves. Some winters are so cold that the island becomes locked in ice.

~~

Even when I visit in June, the waters are rough. A 15.4-mile trip that, on a still day would take around 70 minutes from Onancock, Virginia, takes twice as long on a bucking, writhing sea. The salt-heavy air whips and groans in protest at my first steps on the island.

There are no cars on Tangier other than a couple of small trucks. That’s one reason why, walking down the long wooden dock towards the Main Ridge — one of three seams of high ground that form the island’s rigid backbone — it feels like I’ve traveled not only across space, but time. Modest two-story clapboard homes stand sentinel along quiet streets, the most ornate among them hung with green and red shutters, their fences festooned with colorful buoys plucked from the Chesapeake. The K-12 school, two churches, three restaurants, and a handful of other businesses are clustered around them.

Away from the harbor, the wind mellows. Water pools everywhere, especially along side paths that dip below the water table, worn into the earth by centuries of passing feet. Guts — narrow channels burrowed by changing tides — stripe the island from south to north. Deeply devout Mayor Eskridge erected a stark wooden cross in the marsh just beyond the town’s northern-most bridge. Faded black words across its center read: “Christ is Life.”

The deeply religious community of Tangier was a center for Methodist revival camps in the early-19th century. PHOTO: ALAN GIGNOUX/ALAMY

This is Tangier’s “before.” Working as an archaeologist for the better part of a decade, I’ve seen firsthand what the “after” looks like — how a community can be devastated by environmental change. But the further Tangier slips beneath the waves, the less archaeologists will be able to reconstruct its past. In my lifetime, every single thing I’ve photographed here will be gone. Everything, that is, except the water.

It’s unsettling, walking the paths of this doomed island. More unsettling, however, is the way Tangier plucks at the strands of my own history. Three surnames identify a surprising number of island residents. One of them is mine. I gape at gravestone upon gravestone of the Parks who came before me, men and women who lived their entire lives on this isolated island. At Fisherman’s Corner restaurant, I nibble on “soft crab treasures” fried up by Stuart Parks, who co-owns the restaurant with Mayor Eskridge’s wife.

Later that day, the wind and waves around the island become subdued and sleepy. Even then, as my boat glides out of Tangier Harbor, it’s the Parks Marina that silently bids me a safe journey.

~~

Earl Swift first landed on Tangier in 1994 as an intrepid journalist in the midst of a harrowing 500-mile reporting trip around the Chesapeake. He had only what he could carry in his sea kayak, camping nights in sandy coves, sometimes soaked to the bone in powerful storms that filled his tent with water. Six years later, he returned for a six-week stay on Tangier to report on the “erosion” threatening the island during a time when climate change was the purview of scientists, not the general public. Swift and a photographer spent six weeks gathering evidence of the Chesapeake’s assault on the island. In those days, not even the reporter had a clear understanding of the global threat of sea level rise.

That had changed by his return to Tangier for a 14-month stay in 2016. After years on the sidelines, a basic understanding of the threats posed by climate change and rising seas were finally gaining traction off the island. But on Tangier the conversation hadn’t changed. “Tangier men are always suspicious of science,” he says, due to their deep faith in the literal translation of the Bible. Furthermore, a wariness of government institutions and NGOs stems from a history of dealing with state restrictions on the crab and oyster catches that they’ve long depended on for their livelihoods.

“They believe that the new label [climate change] means it’s a new phenomenon,” Swift explains, when really the sea and wind have been shaping the island since it was first settled. “Now it’s just moving at a breakneck pace.”

~~

Centuries ago, Tangier Island was a sandy Chesapeake refuge. Massive piles of discarded oyster shells and thousands of stone arrowheads are the only remaining evidence of the island’s first settlers, people of the Pocomoke Nation, who likely spent warm summers on the island for centuries before the arrival of European colonists. By the mid-18th century, the island’s first residents were faced with widespread disease and often brutal displacement by colonists; most were forcefully relocated northward or integrated with other tribes on Virginia’s lower Eastern Shore.

Europeans, or more precisely, the crew of Captain John Smith, the English explorer supposedly saved not once but twice by a pre-teen Pocahontas, first laid eyes on the Tangier Islands in 1608. He renamed them the Russell Isles in honor of the doctor who journeyed at his side.

By 1778, Tangier’s first white settlers, Joseph and Mrs. Crockett, and their brood of 10 children, purchased 450 acres (more than half of the island’s current landmass). A slow trickle of settlers followed. Following the Revolutionary War, in 1808, Tangier became a retreat for Methodist prayer camps.

There is no number of soldiers, no stockpile of military artillery, that can fight the battle that will almost certainly be the punctuation point at the end of Tangier’s long history.

In the country’s next local battle, the War of 1812, the British Navy landed on Tangier. Finding the island strategically located and easily defensible, the Brits constructed a garrison, Fort Albion. From there, they launched some of the battle’s most important operations, including an ill-fated assault on Baltimore that provided inspiration for Francis Scott Key’s “The Star Spangled Banner.” Hundreds of African Americans escaping slavery found freedom at Fort Albion but the minutiae of life at the military installment is unknown. The site disappeared under rising water years ago.

During the Civil War, the staunchly Methodist Tangier Island sympathized with the church’s Northern abolitionist faction and became a bastion for like-minded believers from both the North and South. Almost a century later, according to Eskridge, “Tangier had the most people per capita for a community in [Virginia] that served in World War II.” But there is no number of soldiers, no stockpile of military artillery, that can fight the battle that will almost certainly be the punctuation point at the end of Tangier’s long history.

~~

The end of Tangier is the start of a new chapter of the United States that has yet to be written. Tangier, like the Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana — the first 21st century community slated to be resettled in the U.S. due to rising seas — is one of a handful of canaries caught in the climate coal mine.

The abandonment of a homeland due to man-made environmental impacts, though, is nothing new. These experiences fill the pages of the past. In the 1930s, millions were driven from the Dust Bowl in Oklahoma, Texas, Missouri, and Arkansas in search of relief from punishing dust storms. In 1947, Hurricane George forced racially-segregated African American families from the ruins of their Fort Lauderdale homes; 60 years later, Hurricane Katrina upped the ante in New Orleans. Farther back, in the 12th and 13th centuries, endless droughts and deforestation forced Ancestral Puebloans of the Southwest Four Corners region to reconfigure their entire society on the Colorado Plateau, leaving cities that thousands had called home just 50 years prior.

Tangier men refuse to be climate refugees — or at least that’s what one entrepreneur silk-screened onto T-shirts that many around town proudly wore during Swift’s stay. “Victim” is not a role these wizened, self-sufficient watermen are willing to play. “[The Mayor], like many Tangier men, he’s holding out for some sort of intervention, divine or otherwise,” says Swift.

~~

The first time I try to reach Mayor Ooker Eskridge, the weather intervenes. There’s no answer at the town office; not even voicemail picks up. When I try again later, an administrator answers in surprise. The phones have been out all day due to high waves and wind, she says. When I leave a message, she repeats my last name with curiosity as if she’s just discovered a long-lost relative.

Days later, I reach Eskridge at home. When he’s not presiding over the island, he’s a full-time waterman. When I call, he’s just returned from his crab shack where he sorts his daily catch, assigning those of different size, sex, and molting status to tanks and packing crates. Eskridge looms large in Swift’s book — it’s clear the two men developed a rapport during months of island living — and speaking to him gives me jitters like calling up a celebrity might inspire. If he notices, he gives no indication. He’s gracious and kind, his voice soft but resonant with a tidewater twang.

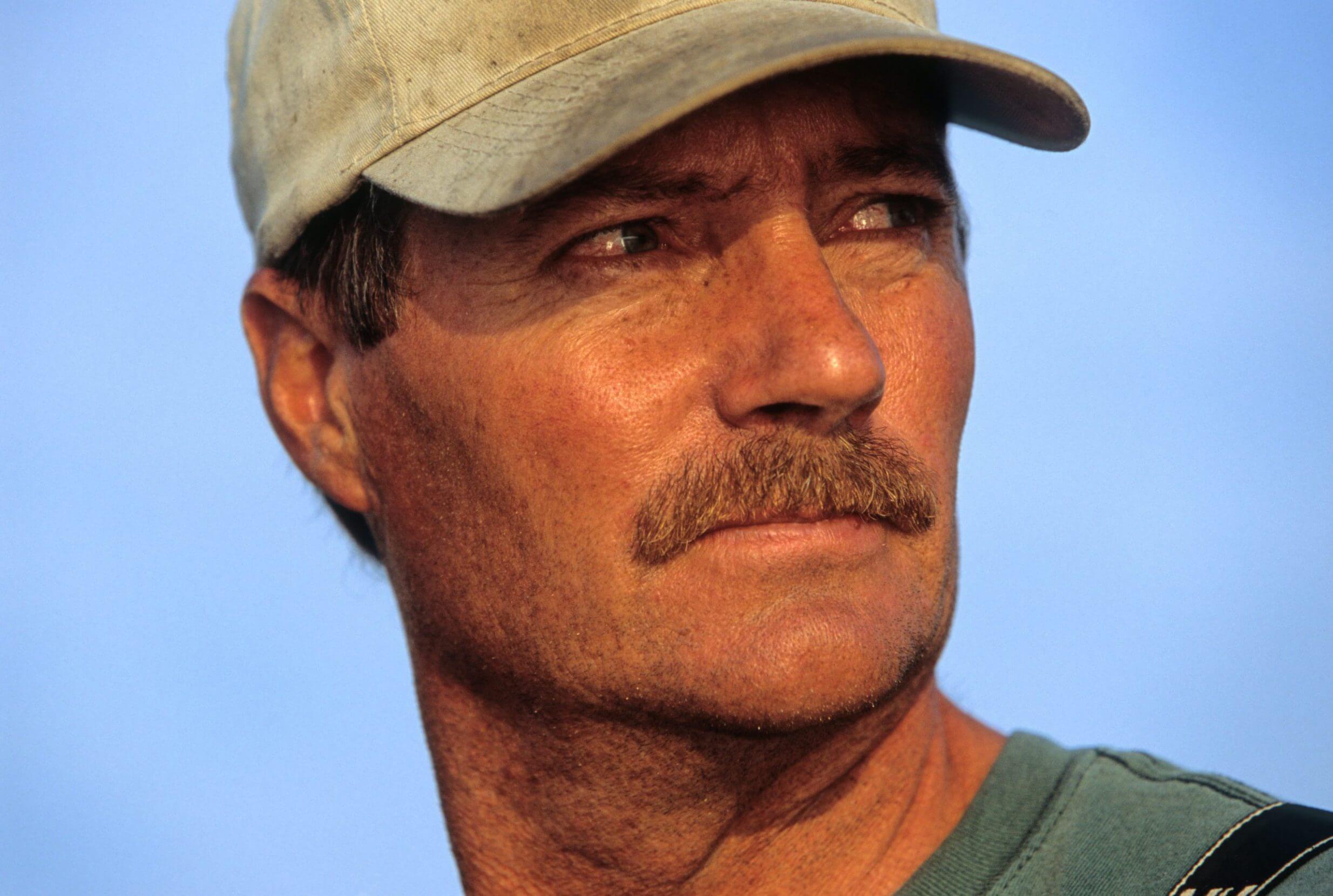

Mayor James ‘Ooker’ Eskridge of Tangier Island is also a lifelong waterman. PHOTO: PETER ESSICK/ALAMY

It’s been two years since his CNN Town Hall appearance and a spot run by the network in June 2017 in which Eskridge claims, “I love Trump as much as any family member I got.” I want to know if Tangier men have seen any changes that might improve the island’s chances of survival, even with a political administration that refuses to admit that climate change is real.

“Yes, definitely we have,” Eskridge says. Three days after his CNN spot aired, his son motored out to Eskridge’s boat in the middle of a workday to tell him the White House is on the phone; President Donald Trump was calling to thank him for his support. According to what Eskridge told Swift after the call, Trump told him Eskridge was “his kind of guy,” adding “you’ve got one heck of an island there” despite never having seen it himself. Within weeks, Eskridge was flying over Tangier with the head of the Department of Fish and Wildlife to scout sites for building a seawall. “This seawall project, jetty project, this has been in the works for almost 20 years,” he tells me. “Without that phone call, I would not be talking to those people.”

The jetty, a breakwater that will block damaging waves from the west side of the harbor, is little more than a band-aid for the bruised and broken island. It could buy Tangier some time, allowing islanders to continue using the harbor which is becoming increasingly pounded by the sea, hampering the movement of boats to and from the island. Alone, though, explains Swift, the jetty is “not going to change anything.” Building a sea wall or using sand dredged from the Chesapeake’s channels to shore up the island could better protect it, but would require millions of dollars and many years to complete. Tangier Island has neither. “What they’ve proposed would be a good thing but with the time it takes to do a small project, I’m not real hopeful on that,” says Eskridge.

Ultimately, the biggest question looming over Tangier Island is not whether it can be saved, but whether it should be.

~~

Data published in the journal “Nature Communications” in October 2019 estimates that, best case scenario, 190 million people will become climate efugees from sea level rise by 2100, up 80 million from previous projections. If high emissions continue, that number will more than triple.

The biggest question looming over Tangier Island is not whether it can be saved, but whether it should be.

With so many people facing displacement, whose homes deserve to be saved? Do we focus our efforts on population centers and industry hubs? Can we justify protecting unique and historically-valuable places like Tangier Island, places that Swift refers to as “the spice in the national dish,” even when around 1/4 of their remaining population of fewer than 500 is already past retirement age?

According to Swift, “what we do [on Tangier Island] or don’t do, will necessarily inform what we do the next time — which won’t be far behind — and the next time after that, and after that. And we’ve got to be consistent because this disaster is going to be so brutal in its effect that our response has to be rational. I would love Tangier to be saved but I think we have to decide how to decide … It’s going to be one of the ugliest things that this country, that any people, has ever been called upon to do.”

While government agencies decide their fate, Tangier men “stay encouraged and press on,” says Eskridge. “This is our home. We’ve been out here hundreds of years. I know that people actually condemn that we are seeking help [but] if they’re not able to save a small community like this then good luck with them trying to save a huge city.”

Shoshi Parks

Shoshi Parks is an anthropologist turned writer of the quirky and fascinating.