Ad Free. Reader Funded.

Hidden Compass is on Team Human. This article was not written by generative AI. Support the journalist and editors of this piece with a direct contribution!

% of $ Goal

Total number of contributions so far:

0

Total amount raised for journalists

$0

"One thing I really appreciated about working with Hidden Compass is that it's a space where there is time for nuance and complexity. By donating, that's what you're supporting. You're able to help us as writers, but also as an outlet, continue to tell these kinds of stories."

- Anna Polonyi, Hidden Compass Journalist

"The reason why I contributed was because the article that I read really resonated with what I was feeling. I felt like the author was in my head... It just moved me and I felt like I needed to do something."

- Hidden Compass Reader

The winter afternoon sunlight filters through the skylight onto my table at a café. Out the window, I see the mansions that flank the opposite side of this narrow cul-de-sac. These old North Kolkata homes blend traditional Bengali, Mughal, and European styles, their ornate facades showcasing Corinthian columns, slatted wooden windows, and intricate cast-iron railings on small, circular balconies. The languid urban canvas, replete with hand-pulled rickshaws rolling down the road, stray cats lazing on ledges, and two elderly men having a quiet cup of tea at a roadside stall, weaves an illusion of a world long gone.

The mansions were residences of affluent Bengali families that did brisk business with the East India Company and generated enough wealth to build these palatial homes. During the early years of the East India Company’s rule, this part of then-Calcutta (now Kolkata) was known as “Black Town.” It was where the “natives” lived. The part of the city where Europeans lived was known as “White Town.”

I have chased stories to far-off corners of the globe, but this time, I am trying to trace the footsteps of James Augustus Hicky, an Irishman who lived and worked in my home city two and a half centuries ago. I don’t know what he looked like. Unlike prominent British men who called Calcutta home during colonial times, no pictures of Hicky exist. I know contemporary records describe him as a “wild Irishman” with a rather mercurial temperament. And I know, as a Kolkata-based journalist, I am tied to Hicky’s enduring legacy. So, once I finish my cappuccino, I set off to explore some of the urban chaos that has lingered since his time.

In the 1770s, Hicky set himself up in this Black Town, away from White Town. Harboring high ambitions, he borrowed money to purchase a trading vessel that would operate on the maritime route along India’s eastern coast between Calcutta and then-Madras (now Chennai).

In 1776, his ship sailed through turbulent weather, and the cargo was badly damaged. When Hicky’s debts fell due around this time, he could not pay them, and his lenders refused his pleas for a moratorium. Hicky entered Calcutta jail as a debtor. This was the Irish adventurer’s first prison sentence.

But not his last.

~~

“Part of Cheringhee, Calcutta” by English painter Thomas Daniell, ca. 1798, depicts the road to Chowringhee. A broad avenue alongside the Maidan open space, it is where some of the grandest of then-Calcutta’s neoclassical villas were situated. Painting: Thomas Daniell / British Library.

Hicky’s story in India started four years earlier, in the spring of 1772, when he undertook the long voyage from London to Calcutta. He was the surgeon’s mate aboard the ship, though he had no formal training in surgery, nor was he nurturing any ambitions in the medical profession. He only wanted to go to India, which many in Europe saw as the 18th-century El Dorado.

The Mughal Empire was disintegrating, and the British East India Company was emerging as the new powerhouse. Chartered in 1600, the company was originally formed to trade on the Indian subcontinent, but later morphed into the world’s most powerful corporation — it even had its own army. At its peak, the British East India Company had more than 250,000 soldiers in its ranks, a formidable power larger than many nations’ militaries.

As the East India Company consolidated its hold over India, Calcutta was blooming with grandiose colonial architecture: riverfront promenades, broad avenues, wide-open spaces for horseback rides, and fashionable clubs.

Hundreds of Europeans were flocking to India, chasing promises of immense fortune. In the 1770s, the average annual earnings in England were £17 per year, but the annual income of a mid-level East India Company official in Calcutta was typically between £200 to £500 per year. Those earnings were often bolstered by private trade and bribes, both officially prohibited but unofficially encouraged across the company. The highest officials diverted astronomical sums, amassing fortunes in just a few years before sailing back home to buy titles and estates and enjoy lives of prestige and luxury. Economist Utsa Patnaik has estimated that Britain siphoned off nearly $45 trillion from India from 1765 to 1938, but a more recent analysis puts that number at close to $65 trillion. The consequences for India were devastating.

When he set out for India, Hicky’s goal was simple: to claim a share of this fabulous wealth and to be part of this money-generating machinery. Instead, he would become instrumental in exposing its corruption and abuse of power. And he would pay a terrible price for it.

~~

It was a shock when people found their city plastered with notices of an upcoming and altogether foreign entity — a newspaper.

It is a steady, persistent drizzle. The raindrops catch the neon-yellow streetlights, adding a momentary translucent glow to their contours before they settle on the dark street.

Central Kolkata will turn chaotic in a few hours, but at 4 a.m., it is quiet, save for the occasional wheezing horn of a passing vehicle. A muted buzz emanates from the pavement where a motley squad — gangly teenagers, wiry middle-aged men, and a few withered old men — remain busy with their work. They are newspaper hawkers, gathering their daily stock from their distributors before embarking on their daily routes.

As I watch the men going about their morning drill, I wonder how many of them are familiar with the name James Augustus Hicky, who left an ineffaceable mark on the history of journalism here — and in the history of the freedom of the press around the world.

~~

When he found himself in debtor’s prison in 1776, Hicky was thankful he had secretly stashed away 2,000 rupees (£200 in those days) with a trusted friend before his arrest. With that money, he bought typesets and set up a printing unit in a bamboo shed he built for himself inside Calcutta’s common jail. He had learned printing techniques as a young man in London, though he had never implemented them in conditions such as these.

Amid the torturous, overcrowded 18th-century Calcutta jailhouse — an inferno suffocating with the putrid smell of decay, despair, and death — Hicky started printing handbills, almanacs, and other documents for the Supreme Court of Calcutta from his jailshed. The income these generated was not enough to repay his loans, but it could at least cover his bills while in jail. Prisoners were required to pay for food, water, and lodging during their jail term.

In the summer of 1778, when James Hicky was released from prison, the cases against him were either dismissed or resolved, and a new path was set out before him.

~~

The winter mornings of January 1780 held a surprise for the residents of Calcutta. In a land that had for centuries relied upon the messengers and horsemen who enabled only slow, person-to-person communication, it was a shock when people found their city plastered with notices of an upcoming and altogether foreign entity — a newspaper.

Hicky had meticulously planned the prelaunch campaign. While he set up the printing shop on Radhabazar Street, a commercial hub just outside White Town, he ensured that notices of his newspaper were posted across the city. On January 29, 1780 — two years after Hicky’s prison release — the first edition of the Bengal Gazette was published. The four-page weekly, edited and published by Hicky, became the first newspaper in India.

From the beginning, Hicky made the paper a platform for serious journalism. In March 1780, Calcutta saw its worst city fire to date. The inferno engulfed more than 15,000 homes. Hicky covered the horrific incident.

“The dreadful havoc the late fire has made amongst the poor Bengalis is almost incredible,” the Bengal Gazette reported, along with the loss of 190 lives, “burned and suffocated by the smoke and flames.”

In his follow-up articles, Hicky highlighted Calcutta’s severe lack of infrastructure, road maintenance, and general sanitation in the areas outside White Town and urged the East India Company to act. It seemed to work. The Company began investing in the city to improve living standards. Even Hicky’s insistent writings on the need to provide assistance to the citizens most affected by the fire were met with a favorable response from the government.

Hicky began to see the power his three-month-old newspaper wielded. He decided to delve deeper into the murky underside of British rule in India. He also changed the phrase below the header of his newspaper to read:

“… Open to all Parties, but influenced by None.”

James Augustus Hicky’s Bengal Gazette, first published in 1780, was the first newspaper in India. An unlikely newspaperman, the surgeon’s mate-turned debtor began to turn his prospects around. Digital Image: Courtesy of Heidelberg University Library.

~~

A gusty wind rustles through Radhabazar’s dense retail hub, the storefronts with textiles, furnishings, and pharmaceuticals spilling onto the cluttered pavement. I am standing at No. 67, a nondescript shop dealing in plasticware. In the fading evening light, the wind picks up, propelling me back two and a half centuries, to when Hicky’s printshop stood at this very spot.

After a few minutes’ walk through the traffic snarls, past a multitude of roadside vendors, and with occasional glimpses of colonial-era architecture, I find myself before the stately façade of Lalbazar, the city’s sprawling police headquarters. During Hicky’s time, this street housed a bustling market. On one side there was the Harmonic Tavern, exclusively for elite Englishmen, hosting balls and banquets. On the other stood Calcutta’s infamous jail, where prisoners struggled for daily survival with nooses and gallows on open display. Hicky had been an inmate here as a debtor.

And then he had fought against all odds to stay out of that hell a second time.

~~

Five years after Hicky’s first prison term began, he was yet again in the Calcutta Supreme Court facing trial. In five short years, the Irishman had evolved from a bankrupt maritime trader into an investigative journalist influential enough to spook the all-powerful East India Company.

This time, the charges against Hicky had nothing to do with insolvency. They were far more serious.

On June 13, 1781, Hicky was brought into the courthouse before a grand jury of 23 members, most of them Company servants and contractors, and Chief Justice Sir Elijah Impey to hear the charges being leveled against the journalist.

Five counts of libel were brought against Hicky. Two were for defamatory articles on Governor-General Warren Hastings, calling him a despotic “Great Mogul” for his autocratic policies and a disgraceful, wicked man. The second was for the insinuations that Hastings had erectile dysfunction. The third libel charge was for the provocative writings that the court maintained could result in a mutiny of the armed forces. Two more charges were brought by a German missionary for Hicky’s article “For the Good of the Mission,” which accused the missionary of embezzlement of church funds and said he was driven by “filthy lucre and detestable avarice.”

The grand jury agreed Hicky should be charged. Impey proposed a bail amount of 40,000 rupees (£4,000). It was twice the amount Hicky earned in a year.

Unable to post bail, Hicky prepared for his trial from Calcutta jail.

~~

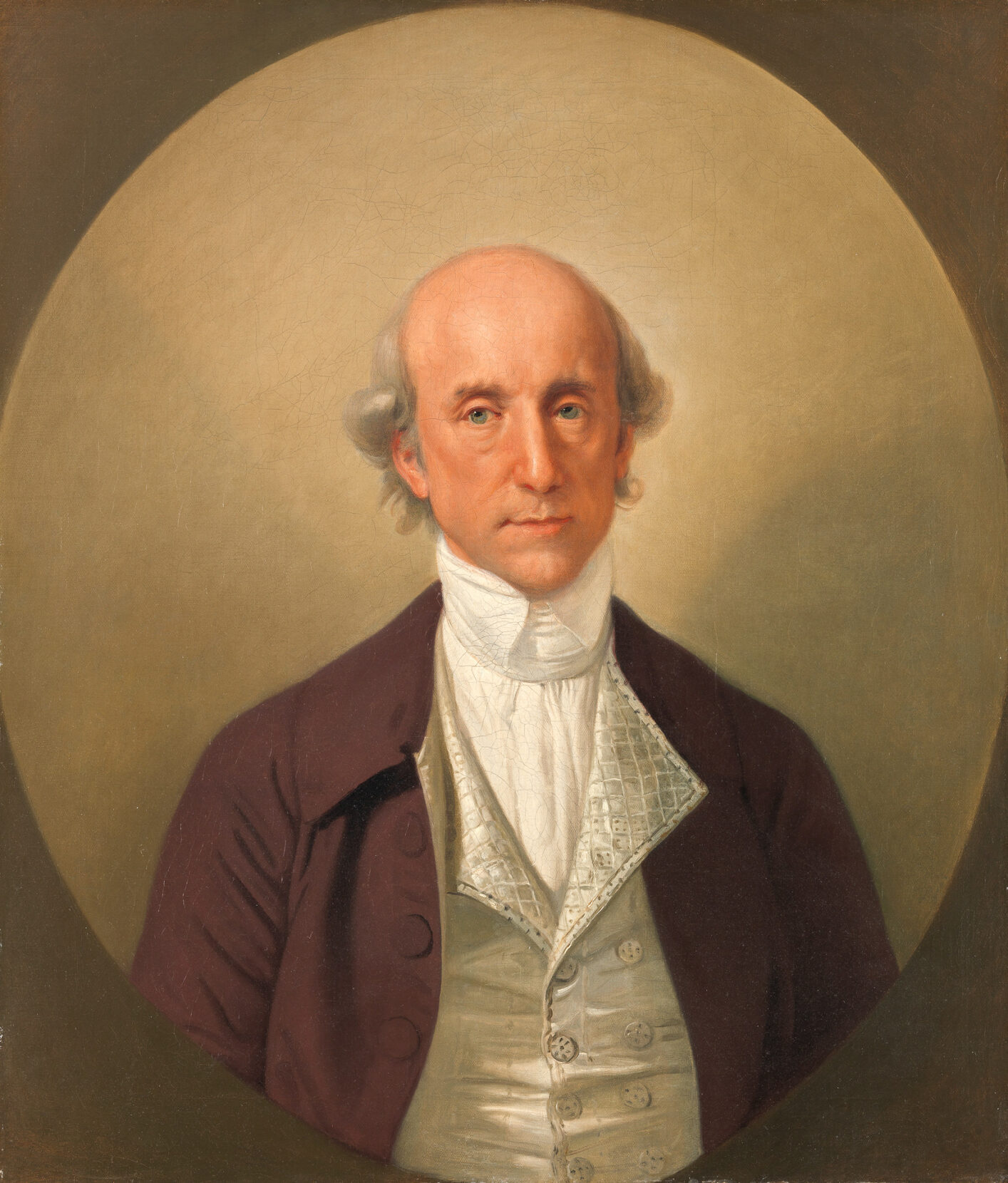

A portrait of Warren Hastings, ca. 1783, by German painter Johann Zoffany. Painting: Johann Zoffany / The Paul Mellon Collection at the Yale Center for British Art.

1772, the year in which Hicky landed in Calcutta, was also significant for Hastings. He became the governor of Bengal, in charge of the East India Company’s affairs in British-controlled India.

At 40 years old, Hastings looked the part of the 18th-century English statesman — mild-mannered and scholarly, with a receding hairline. His genteel appearance belied a strong character that aligned with his unwavering belief in interventionism.

He completely overhauled the administration of Bengal to bring it directly under the Company’s control, remodeled the judiciary to centralize justice under the East India Company, and introduced several revenue reforms, including the appointment of the Company’s own tax collectors, which ensured the collection of taxes and revenues that went directly to the Company’s coffers.

Hastings’s regime, first as governor of Bengal and then as the governor-general of British India, thus marked a phase in which the East India Company transformed itself from a commercial enterprise into a territorial power. It was a power characterized by systemic corruption stemming from nepotism and no-bid contracts.

These staggeringly lucrative contracts, which were mostly secured by people close to Hastings, often bypassed competitive bidding and were issued in defiance of British law. In one contract to repair river embankments (poolbundy in Hindi), the old annual contract of 25,000 rupees (£2,500) was replaced by another contract for 90,000 rupees (£9,000), though the deliverables did not change. It was given without a bid to Archibald Fraser, the cousin of the chief justice of the Supreme Court of Calcutta. That chief justice was Sir Elijah Impey.

~~

Hastings, however, was not content. His big dream was to further expand the Company’s political territory, but he was facing multiple challenges: The mighty Mysore kingdom of South India posed a formidable threat, and the Maratha Empire, which controlled major parts of central and western India, was skeptical of the British. France, already at war with Britain in America, was forging an alliance with Mysore and had a sizable legion stationed in South India. Hastings would eventually break the hostile coalition and make a temporary peace with the Marathas by 1782.

But in November 1780, amid the political turmoil, Hastings ordered a march of the Company army all the way from Calcutta to Madras — a nearly 1,000-mile journey on foot through unrelenting weather and unknown terrain.

Hicky would report the march of the troops in detail, based on information leaked by disgruntled junior officers. The journalist wrote at length about the plight of the soldiers, who were forced to march onward without pay for months and with inadequate rations and supplies that resulted in soldiers ravaging villages along the route. Many soldiers deserted or died.

The incisive reports sent shock waves across Calcutta.

~~

This must be the place where it stood, I think to myself.

From Lalbazar, the expansive red-brick neoclassical façade of the Writers’ Building is an easy stroll of less than a half-mile. The cluttered urban textures soften here with a balmy, landscaped patch of green opposite the iconic late 18th-century building that served as the state’s official secretariat building until a decade ago. A two-story building with Ionic columns and ornate balustrades once stood beside it: the Supreme Court of Bengal, with jurisdiction over British-controlled India.

On June 26, 1781, Hicky was dragged from his prison cell to this packed courthouse, where a jury sat in red robes around a green table in the center of the room. His trial began.

A stint as a law clerk in his younger days in London had given Hicky exposure to the British legal system, and though he had legal counsel, Hicky fought the case himself. His defense arguments were built around a simple point: freedom of the press.

Hicky claimed he had a right to print. He tried to convince the jury that his writing, plus printing and publishing articles penned by others, could not be taken as proof of malicious or seditious intent. He cited the case of Henry Sampson Woodfall, in which the jury refused to find the printer guilty of malice for publishing an anonymous letter criticizing the prime minister. Hicky claimed that Woodfall’s case set a precedent, but he was making his arguments in a courtroom overseen by a man he had once accused of corruption.

~~

Economist Utsa Patnaik has estimated that Britain siphoned off nearly $45 trillion from India from 1765 to 1938, but a more recent analysis puts that number at close to $65 trillion.

In April 1781, just months before defending himself in court, an emboldened Hicky launched an offensive through a series of articles directly aimed against Hastings. The articles not only focused on the corrupt Company practices under Hastings, but also vehemently criticized his policies of conquest, arguing that his ambitions for total domination of India drove the Company into illegitimate wars with native kingdoms.

Hicky adopted a characteristic satirical style that addressed Hastings as a “Great Mogul, seized with a fit of Dispondency and Political despair,” and nicknamed Sir Elijah Impey “Lord Poolbundy,” implying his shady involvement in the river embankment contract. Hicky alleged that the contract was given to Impey’s cousin because Hastings wanted to influence the judiciary.

Hicky was crossing swords now with two of the most powerful men in British India — the governor-general and the chief justice, who were close allies.

~~

Once the arguments in Hicky’s case were made, Sir Elijah Impey gave clear indications to the jury that they should find Hicky guilty.

In the sweltering summer heat, the 23 members retired to a juror’s residence and deliberated over the case. The session lasted from the afternoon of June 26 into the wee hours of the next day.

In its June 25 edition, Hicky’s Bengal Gazette printed a warning: if Hicky were to be convicted, “we shall be in the Condition of the sheep … when our Dogs, our Guardians, are gone our House may be robbed whilst we sleep.”

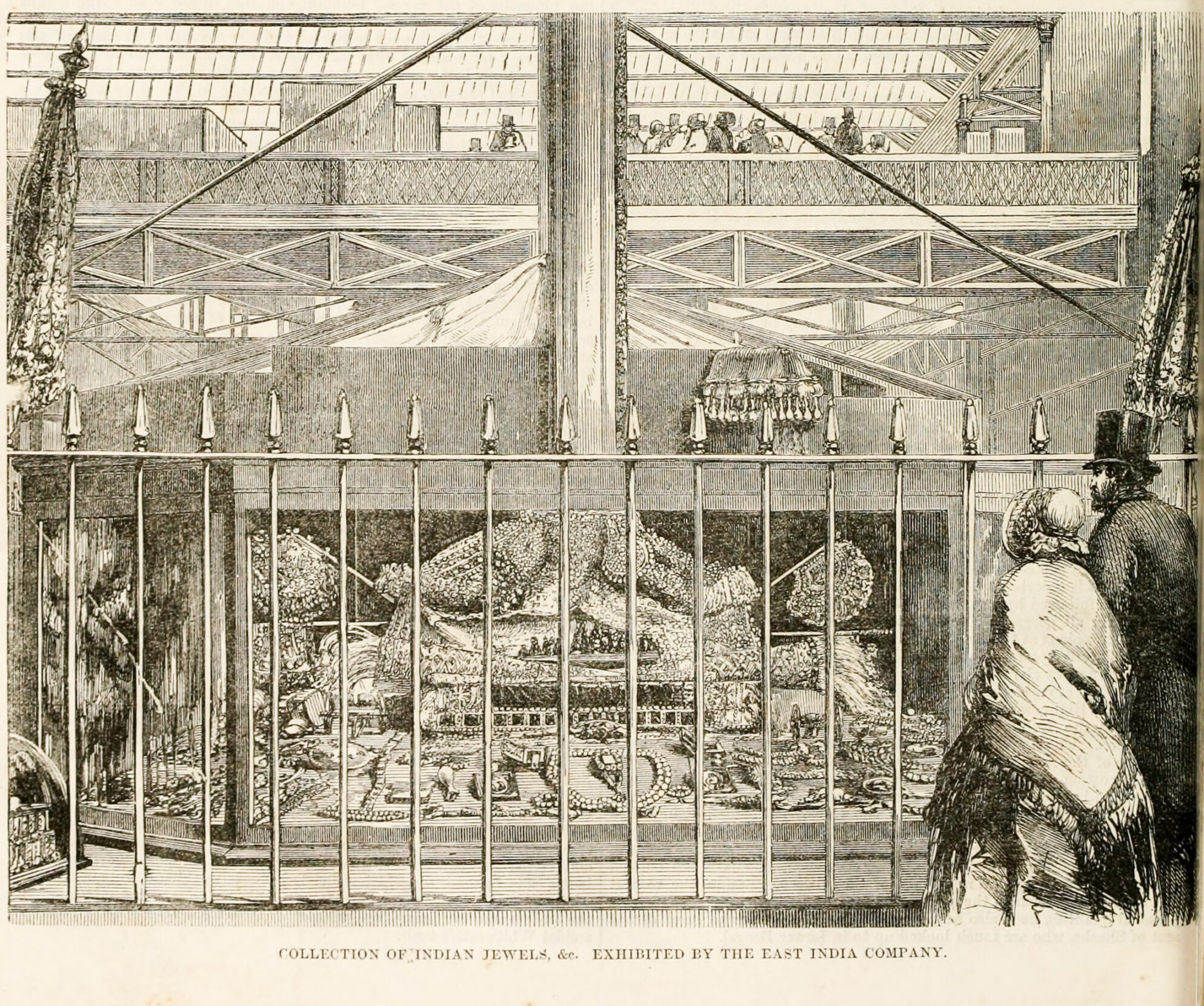

An illustration of people viewing Indian jewels displayed by the East India Company published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Historical Register of the Centennial Exposition, 1876. For nearly two centuries, Britain drained tens of trillions of dollars from India. In 1851 at London‘s Great Exhibition, some of that wealth went on display when these jewels, taken from India, were exhibited for an estimated 6 million visitors. Illustration: Unknown artist / Smithsonian Library.

~~

In the months before his trial, Hicky’s paper had lobbed critiques at the Company and the way it paid and promoted members of its army. Hicky printed letters by junior European cadets and presented the plight of the Indian foot soldiers who fought at the lowest rungs. Their pay was always in arrears, forcing them to borrow money at exorbitant rates, trapping them in a vicious cycle of debt.

But where Hicky stood out was his unique stance on war. The British had suffered their worst military defeat in India in September 1780, when a South Indian king completely decimated the Company army in its campaign for power. The Bengal Gazette not only published scathing reports on the loss of British lives due to the incompetence of Hastings’s trusted commander in the war, but also reported on its aftermath — how the price of grain shot up thirtyfold, leading to famine and the deaths of thousands.

Hicky’s unusual antiwar perspective and his focus on the humanitarian tragedies it caused gained Hicky an international audience. British and American newspapers reprinted his articles. French and German journals translated his reports. Within nine months of its inception, the Bengal Gazette was a resounding success, a powerful independent voice hell-bent on telling the truth.

But mere months after the Bengal Gazette’s first printing, preparations were already afoot to launch the second newspaper of Calcutta.

~~

On November 18, 1780, the first edition of the India Gazette was published by two Englishmen: Bernard Messink and Peter Reed, neither of whom had any prior knowledge of printing or journalism. Messink had been a successful thespian, and Reed was an influential member of Bengal’s thriving salt trade. But they were confident of turning their new newspaper into a profitable business. After all, they had the patronage of the man holding the highest office in British India — governor-general Warren Hastings.

The editorial policy of the India Gazette reflected Hastings’s narrative — the right of the British to colonize and rule. The articles focused on establishing British superiority over the native population of India, providing tips on chivalrous manners for young British men, and celebrating the Company’s trade policy. The paper became the de facto mouthpiece of the East India Company.

Hicky’s newspaper still sold more copies but lost many affluent subscribers to its competitor. What’s more, the India Gazette launched a direct attack on Hicky, labeling him a disloyal citizen and calling for censorship of his paper, accusing him of spreading dissent and subverting British interests.

Then Hastings passed an order granting free postage to the India Gazette. To Hicky, this confirmed a conspiracy against him. Alarmed that this might further deplete his subscriber base, Hicky decided to pay his subscribers’ postage.

A media war had begun.

~~

Hicky went on the offensive. He started with a scathing article on Simeon Droz, who headed the board of trade and was very close to Hastings. In a particularly spiteful article, Hicky described Droz, whom he believed to be the mastermind behind the India Gazette, as a “premeditated dark and deep assassin, the slave and tool of a party.”

Hastings retaliated. A decree was passed that forbade anyone from mailing the Bengal Gazette through the post office.

Hicky ran a front-page feature, calling the order illegal under British law and wrote, “The weakest, The meanest, The most cowardly souls are ever the most cruel and revengeful.” He employed couriers to deliver his newspapers outside Calcutta. The ruckus became the talk of the town, and Bengal Gazette subscriptions shot up despite the crackdown.

~~

The empire struck back.

On the afternoon of June 12, 1781, Hicky found his home encircled by an armed squad of policemen. They came with an arrest warrant for libel, directly from Chief Justice Impey. The journalist was taken into custody and jailed — just as he had been years earlier when he was unable to pay his debts. But he knew this time he had a longer, tougher battle ahead.

~~

I know, as a Kolkata-based journalist, I am tied to Hicky’s enduring legacy.

Two weeks later, amid the stifling, suffocating tropical summer heat, the trial began — a courtroom drama, where Hicky defended his case admirably. His arguments were rooted in the principle of freedom of the press, a fundamental right he claimed was unimpeachable, citing a number of British precedents.

Impey was unmoved. The chief justice gave clear indications to the grand jury that Hicky must be declared guilty.

But Hicky’s arguments impressed the jury. They adjourned to Justice John Hyde’s house, and the deliberations went on from late afternoon to the next morning.

The next day, when the courthouse opened, the jury delivered its verdict.

They had found James Augustus Hicky not guilty.

Impey was livid. The chief justice made a furious demand for reconsideration of the verdict, which the members of the jury flatly refused, and their verdict stood.

~~

Hicky may have been triumphant in his courthouse argument for a free press, but his editorial approach often pushed the line. On one side were the acerbic critiques, vilifying those in power. On the other side were the claims that defamed his targets.

Hicky used comical nicknames for some of Calcutta’s well-known public figures. Edward Tiretta was Calcutta’s superintendent of roads and the city’s civil architect (a neighborhood in the city, Tiretta bazaar, is still named after him). A flamboyant Venetian with ties to Casanova, Tiretta was knowledgeable in his work but often made a funny picture of himself, speaking in a strange melange of French, German, Portuguese, and Hindustani, his amalgamated speech loaded with the choicest expletives in each language. Hicky named him a “Nosey Jargon,” having a “happy turn for Excavations and diving into the Bottom of things” — a reference to Tiretta’s job, possibly infused with a euphemistic jab at Tiretta’s sexual orientation (a claim that was likely untrue).

Hicky’s editorial stance was sometimes contradictory. He held a patriarchal outlook, emblematic of his times, relegating women to a subservient role in society. But he also touched upon the taboo subject of female masturbation and printed an article on women’s right to control their own sexuality. And while he viewed India with a colonial mindset, again typical of his times, he also covered news of the poor native citizens of Calcutta. These stories of the plight and hardship of commoners could have been lost in the annals of time if not for Hicky.

But he also couldn’t hold back the personal attacks, even hinting that Hastings was suffering from stress-induced erectile dysfunction. So it was no wonder that Hastings attacked Hicky on multiple fronts.

~~

On June 27, 1781, the same day that he received a not guilty verdict in Impey’s court, Hicky faced trial for another count of libel against Hastings before a different judge and jury.

Interestingly, no details of this trial have survived except the verdict announced that same day: guilty. Over the next two days, Hicky was found guilty of two more charges: one of libel for accusing a Company official of corruption, and another libel charge for publishing articles calling for a mutiny of the Company’s army against the dictatorship of Hastings.

The verdict was decided, but the sentence would be delivered later. For the next four months, Hicky sat in his jail cell awaiting his fate.

Eventually, he was sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment and 2,500 rupees (£250) in fines, with a clause that he would be imprisoned until the fines were cleared. If Hicky had found the judgment not as severe as he had expected, his relief was short-lived. Four days later, Hastings brought a fresh suit against the journalist. This time it was a civil suit for the same libel for which the jury had found Hicky not guilty.

~~

“… Open to all Parties, but influenced by None.”

The Bengal Gazette still managed to get published thanks to Hicky’s motley squadron of anonymous contributors. With Hicky’s imprisonment, the newspaper’s tone turned darker, publishing a bitter tirade against Hastings and, more importantly, against British rule in India. It claimed that the East India Company was violating the foundations of British law at will in India.

The newspaper leaned on its forte — satire — by printing a mock playbill in an edition in January 1782. Hastings was portrayed in the lead role as the Dictator Sir Francis Wronghead, with a song provocatively titled “Know then war’s my pleasure.” Impey was cast as a traveling justice taking affidavits gratis, with a motto on his chest that read “Datur pessimo” (Giver of wickedness) and “all was false and hollow.”

But one of the justices of the Supreme Court, John Hyde, received milder monikers in the mock playbill — “Justice Balance” and “Nobody” — as if he played a more honest role.

~~

Journalist Andrew Otis, in his painstakingly researched book Hicky’s Bengal Gazette, has written about secret codes in the notebooks of John Hyde. Carol Johnson, a New Jersey-based professor, deciphered these codes, in which John Hyde had clandestinely recorded the judicial corruption of his fellow jurors. The findings corroborate Hicky’s reports in his newspaper and, in a way, confirm the allegations he made.

Following the mock playbill, Hastings brought four more legal actions against Hicky. The journalist filed as a pauper, unable to bear the legal costs any longer. Hicky hoped that in doing so, his printing press and equipment would be unencumbered, even if his property were to be seized to pay the fines and court costs. The British legal system gave him that protection.

However, without citing any reason, the court reversed its original order protecting Hicky’s press from attachment and passed a directive to the city sheriff to confiscate all his possessions, including his press, and put them up for auction.

In March 1782, Hicky’s Bengal Gazette printed its last edition, ending its two-year run.

~~

A group of young men play cricket on the Maidan while the Victoria Memorial peeks out from behind the trees in the distance. Honoring Queen Victoria, the memorial is a massive 20th-century marble monument erected by the British during the colonial period to celebrate the British Empire in India. Photo: Diana Jarvis / Alamy.

The Maidan is as elemental to Kolkata as Central Park is to New York City. Spread over roughly 1,000 to 1,300 acres, the huge swath of green space lies at the heart of the city’s urban matrix, hemmed in by colonial-era landmarks such as the Victoria Memorial, St. Paul’s Cathedral, and Fort William, as well as some modern skyscrapers. This is where Kolkatans assemble for cricket and soccer matches, Sunday picnics, budget-friendly dates, and evening joyrides on horse-drawn carriages.

This morning, I wander aimlessly through the rippling sea of green below a thick layer of wintry fog, a couple of horses ambling at a distance in the pearly-white mist. In 1781, Birjee jailhouse stood here, though no traces of the facility remain now.

Beginning with his first 1781 trial, Hicky was confined here. Stripped of his means to pay the fines imposed by the court, Hicky was stuck. Not paying the fines meant he would remain in jail even after his prison term ended.

Miserable and demoralized, Hicky became so impoverished that he could no longer afford his rented home in Calcutta. And so his family moved in with him, living amid the filth, squalor, and other prisoners.

Hicky shot off a series of desperate petitions to the court to forgive his fines, but all of them fell flat. A written plea for public support had scant response. People were now wary of siding with him and getting on the wrong side of the powers that be.

Hicky seemed destined to spend the rest of his life in his prison cell.

Amid the torturous, overcrowded 18th-century Calcutta jailhouse — an inferno suffocating with the putrid smell of decay, despair, and death — Hicky started printing … from his jailshed.

~~

But thousands of miles away, there were fresh developments. The details of Hicky’s case had reached England and stoked a public outcry. Sir Elijah Impey had been recalled to England. Warren Hastings decided to close his affairs in India amid growing criticism and sailed back to England, ending his 12-year run as governor general. During his term, he had consolidated the foundations of Company rule, which would continue for many more years until the First War of Independence — or Indian Mutiny, as it’s often called in the West — in 1857. Soon after returning to his homeland, Hastings, perhaps a scapegoat for systemic ills, faced an impeachment trial. The trial would last seven years before he was acquitted.

One of Hastings’s last acts as governor-general was to order the Supreme Court to forgive Hicky’s fines and release him from jail. The radical change of heart possibly stemmed from the effective elimination of the threat the journalist had once posed to him. During Christmas week of 1784, after spending three years in jail, Hicky was finally a free man.

“A View of the Tryal of Warren Hastings Esqr. before the Court of Peers,” ca. 1789. Upon returning home to Britain, Warren Hastings faced a lengthy impeachment trial. Illustration: Robert Pollard, by Francis Jukes, after Edward Dayes / British Library

~~

Little is known about Hicky’s later life, except that he lived in poverty, and a couple of attempts to relaunch his newspaper failed. Over the next two decades of his life, Hicky faded into oblivion.

In the summer of 1802, Hicky boarded a Canton-bound ship from Calcutta. It was a last-ditch attempt to reverse his fortunes through a business consignment, but he could not complete his journey. A broken man of irreversible ill health, Hicky died on board, and his body was dumped into the South China Sea.

But his legacy endured.

~~

I walk through the green, the mellow rays of the morning sun now glinting off the fresh dewdrops on the grass, and think of the wild Irishman who traded his career and life in his fight for a free press.

He could not have known then that his trailblazing paved the way for a number of newspapers established in the years following his incarceration — papers that would collectively shape journalism in India. Some of their founders, like Thomas Jones and Richard Tisdale of the Bengal Journal (founded in 1785) and Paul Ferris and Archibald Thompson of the Calcutta Morning Post (founded in 1792), had been trained by the man himself.

And though the Bengal Gazette had but a two-year run, the newspaper had a resounding impact on policy. It was largely because of Hicky’s newspaper reports that the British Parliament passed Pitt’s India Act of 1784, which aimed to improve administration in Britain’s largest and most profitable colony. The reports were also instrumental in triggering the long impeachment trial in the British Parliament for corruption and abuse of power against Warren Hastings.

Meanwhile, the city James Hicky called home for the last three decades of his life evolved into a thriving literary center with a vibrant publishing industry. Some 200 years after Hicky ran his last edition of the Bengal Gazette, a historic street food hub in the heart of the city’s business district was renamed in his honor.

A brisk 30-minute walk from Maidan, I head toward the bustling stretch of modest eateries that provide sustenance to Kolkata’s working class, in search of a refreshing cup of masala chai. Far now from the mansions of North Kolkata, I glimpse this metropolis’s enduring sense of shared community, here on James Hicky Sarani — James Hicky Street.

Sugato Mukherjee

Sugato Mukherjee is a Kolkata, India-based photographer and writer whose work on the sulfur miners of East Java was recognized by UNESCO.