Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

I click into a harness and climb into the whisker netting of the bow protruding from the ship. The sea sprays my ankles. It’s about half a dozen shimmied paces across the netting, each rope just far enough apart that a misplaced foot could slide through.

I’m shivering, but can also feel the sun searing my cheeks. The temperature seems to roll with every dip and jump. I calm my racing heart and face the uncatchable wind that has gathered across thousands of miles.

I pivot around to enjoy the space, which is like a hammock hanging under a wooden beam thicker than my body. From here, my floating home looks like a moving monument. This close to the waterline, my view morphs as if I am looking through a fisheye — the curve of the earth more pronounced, the ocean becoming more expansive with each passing second, my own body an ever-dwindling dot.

I have followed a man long-dead to the Tasman Sea, each of us restless twenty-somethings in pursuit of grandeur. Out here, the 200 years that separate us hardly register. His words, written in 1835, flit to mind:

“It is necessary to sail over this great ocean to comprehend its immensity,” wrote Charles Darwin while sailing toward New Zealand, marveling that “moving quickly onwards for weeks together, we meet with nothing but the same blue, profoundly deep, ocean … we do not rightly judge how infinitely small the proportion of dry land is to water of this vast expanse.”

Time exhales, gathering and releasing. The past and future alike seem to rise and flatten like the waves.

~~

During its 734 days at sea, the Darwin200 expedition made landfall at each of the 31 major ports of call that Charles Darwin visited aboard the HMS Beagle in the 19th century. Photo: Jordan Winters.

Three days before, I joined 30-some others on board the Oosterschelde from the dock of Hobart, Tasmania. A crowd formed at the pier to watch.

The crew untethered the ship from the island, and we waved like dignitaries. Bystanders on shore held up their phones, hoping to capture the craftsmanship of the three-masted schooner, her bowsprit like a narwhal tusk, and the swoop of her 164-foot deck. A gust kicked up the huge Dutch flag at the back, the red band luminous in the sun.

Our heading was set on the trail of Darwin’s historic round-the-world voyage on the HMS Beagle. The journey, which lasted from 1831 to 1836, ultimately set in motion his theory of evolution by natural selection.

His ground-breaking scientific treatise, On the Origin of Species, began by giving credit to that formative experience upon its publication in 1859: “When on board H.M.S. Beagle, as naturalist, I was much struck with certain facts …. in the geological relations of the present to the past inhabitants.”

Nearly two centuries later, a rotating cast of volunteer crew, researchers, students, and filmmakers like me had come together from more than 40 countries to follow in his wake. Called Darwin200, our expedition would spend two years at sea altogether, gathering as many of our own facts as we could. We pointed magnifying glasses, filled petri dishes, and clicked camera shutters to document, study, and conserve hundreds of species, both those that inspired Darwin’s curiosity and others outside his scope.

Darwin would have been insufferable as a bunkmate, at a minimum, for the morbid collection of dead birds he kept …

Young scientists with ambitious questions pitched field research along the route, from the Azores to French Polynesia. Selected researchers were paired with local organizations to collect new data, such as counting howler monkeys in Brazil. Sometimes, they got creative to help communities, like when they prototyped 3D printed irrigation valves for farmers in the Galapagos.

Backed by Sylvia Earle, Jane Goodall, and even Darwin’s own great-great-granddaughter, Sarah Darwin, the journey was conceived as an homage to Darwin’s radical notion — that biology is a time machine.

On top of our personal projects and the occasional delusion of grandeur, my shipmates and I had other looming burdens to contend with — a larger-than-life legacy and the blinders of nostalgia. I was there to take it all in.

~~

Other smaller vessels had come out to guide us out of the bay, forming a small flotilla true to sailing tradition. The serenity didn’t last long, though. The deck absorbed the heavy slap of sails and running work boots as we began setting sails. Each of us lined up along a rope and began pulling. Expert hands guided clumsy ones, and rope slowly draped into coils on the red deck.

The Oosterschelde is also an emissary from another era, first setting sail in 1917 and undergoing restoration in 1988. When I joined it, the ship had been at sea for a year and a half, tracing the outline of South America and the Galapagos before island hopping the Pacific to here, the liminal space between Australia and New Zealand.

A monument of Dutch shipbuilding, the restored Oosterschelde features three masts that rise 118 feet, which is about as tall as a ten-story building. Photo: Jordan Winters.

Those first few hours on board felt like my first day of school. In the weather-lined faces and cigarette-stained fingers of the crew, I came to know tall ship die-hards, Southern Ocean aficionados, and a few bohemian retirees giddy to test their mettle in the spartan living of pre-industrial quarters.

I fell somewhere between the history geeks and the more swashbuckling sailors. I had spent years racing modern yachts with my father, and felt at home among the chummy sailors who made dated jokes but always had your back when danger inevitably came knocking. But at the end of those nights when the regatta was won or lost, I felt as if I was going in circles — because we had been, literally. I needed a mission. Darwin200, with its global ambitions, fit my personal bill.

Everyone else’s main objective was to propel us forward, to get us close to our destination safely through the sweat on their brow. And though my fingers itched for rope burns, my calluses would get a rest. As documentarians of different varieties, Darwin and I were both outsiders on the ship, not quite crew but more than passengers. I trusted these waters still held plenty of discovery if I could just see the world through his eyes.

~~

I have followed a man long-dead to the Tasman Sea, each of us restless twenty-somethings in pursuit of grandeur.

In my free moments, I explored nearly every inch of the Oosterschelde. In the saloon, our common space below deck, a dark wood great hall table dominated the space, our de facto reading nook with heavy leather armchairs. Dogeared copies of Darwin’s diaries floated between this and their proper place in the glass cabinet (our “library”) behind the bar table, which functioned as the “lab,” stocked with microscopes and kits of water sample equipment.

I flipped through our patron saint’s diary at random, intercepting him at different points on his voyage. Most people picture a bearded Darwin in his later years, but in those pages, I met the young man who was on the Beagle. I invited his company more as a drinking buddy than professor.

To the disappointment of his father, Darwin was an average student with no stomach to be a doctor. But if his journal was any indicator, he was sassy, curious, and outspoken on social issues, making him a great candidate as the ultimate personality hire — brought on board not because he had shining academic accolades but as a professional dinner companion to Captain Fitzroy. His moods and judgments reveal not an objective scientist as much as a man who was wrestling with God and slowly detaching from plans to join the clergy upon his return.

“Certainly [I] was never intended for a traveler; my thoughts are always rambling over past or future scenes; I cannot enjoy the present happiness for anticipating the future; which is about as foolish as the dog who dropped the real bone for its shadow,” he mused.

When the rolling of the ship made reading hard, I tossed the journal back onto the couch and climbed the awkwardly high stairs, wrapped in a brass railing, to the red main deck. Sunshine gave way to rain that gave way to cold sun again, as our last rocky waypoints became toothpicks in the jaw of Bruny Island and Cape Pillar.

Passengers and crew members of the Darwin200 expedition celebrate the holidays at sea in the elegant saloon of the Oosterschelde. Photo: Jordan Winters.

~~

I don’t remember the exact moment the coast blinked away. It just did. The next land we would see would be the southern tip of New Zealand’s South Island. With each hypnotic rock, I adjusted to the rules of the sea, where time, though governed strictly, had become amorphous.

At the double ring of the meal bell, everyone bellied up to one of the three huge harkness tables lit by chandeliers between the skylights. The captain warned us that we had to hold on to the bolted tables if we wanted to stay in our chairs. Cutlery rattled in the drawers, and glasses dragged loudly across the tables despite our no-slip placemats. Constantly clenching my core just to sit still and not slide made me ravenous.

I made the mistake of looking up at the young, off-duty naval officer onboard across from me. He had a glassy look. He set his fork down, and his uneasiness started to form in my own stomach, as if it was contagious. I swallowed defiantly. Then the sound of chair legs grating across the wood floor erupted as we both pushed back from the table and beelined for the bathroom. I threw up dinner and lunch.

Darwin, a true geologist, loved terra firma and hated sailing. “I hate every wave of the ocean, with a fervor, which you, who have only seen the green waters of the shore, can never understand,” he wrote to his second cousin when the Beagle moored in Sydney, Australia, in 1836. In fact, he spent a mere 18 months aboard the ship, out of the five-year-long circumnavigation, often opting for extended explorations by land.

I popped a Dramamine, and I honed my poor vision on a wave in the middle distance, hands clutching the metal railing. I decided to focus on what was finite instead of trying to swallow the enormity of the ocean beyond one crest. It helped keep the bile at bay. One curl of water, the extension of the other, a reminder of why it’s so hard to know where one thought begins and another ends here.

~~

On a dark night, I looked over the edge of the boat to see ghostly spirals, several feet long, pulsing faintly.

Still weak the next morning, I strapped my camera to my chest and got back out on deck. Sailors’ bodies crammed between masts and the exterior of the captain’s quarters to get purchase. Elbows bumped into heads. We counted down “one, two,” and pulled; “one, two,” and pulled.

Just when I thought I had gotten comfortable with the clunky jargon of the maritime terminology of a bygone era — ratlines, yards, bluntlines, and some more ominous features of the ship, like a widow maker — the peculiars of the old ways found new ways to catch my eye.

I watched with bated breath as Dan, the youngest crew member at 19, hooked his leg around one of the booms (the swinging wooden beam under the sail) and shimmied 20 or 30 feet in the air over the fast-moving ocean below. His whole weight was supported by the tension between his boot and calf. Moving with the swells was instinctive. He was dedicated to fixing a stubborn knot as if the death drop below him was nothing but a nuisance.

I clicked my camera.

Once the task was finished, we went back to our murmuring conversations as we loitered between one set of railings, then another. I held onto each detail with clenched fists, collecting SD cards full of memories, while other crew members wrote meticulous notes about our latitude and longitude.

The expedition comprised a rotating cast of volunteer crew, researchers, students, and filmmakers from more than 40 countries. Photo: Jordan Winters.

I found myself doubting what portrait could possibly rise out of this messy pile of unorganized, haphazard information. Darwin kept 770 pages of diary and 1,750 pages of notes, plus 12 catalogs detailing the 5,436 skins, bones, and carcasses he collected.

Trying to imagine raw observation in Darwin’s time — having to trust his eyes for truth — felt like trying to grab the wind.

~~

Early in his Atlantic crossing, Darwin tossed a bucket overboard and scooped up water. In it, he found the secret lives of plankton: “Many of these creatures so low in the scale of nature are most exquisite in their forms and rich colours.”

They were the first of an estimated 1,400 specimens he collected, soon to be joined by legions of finches, fossils, and ferns — as well as small Galapagos tortoises brought aboard as pets.

On a dark night, I looked over the edge of the boat to see ghostly spirals, several feet long, pulsing faintly.

“What is that?” I asked, also slightly panicked that phantom sea snakes were trying to burrow into our hull. One of the deckhands, Timo, a bearded and bald Swiss man, shrugged. “Just salps,” he responded.

Salps are translucent, sometimes bioluminescent, marine animals that are part of the largest migration of life — from the depths of the ocean to the surface — which happens every night. They rely on the darkness for protection from predators.

Salps remind me how easy it is to miss little immensities.

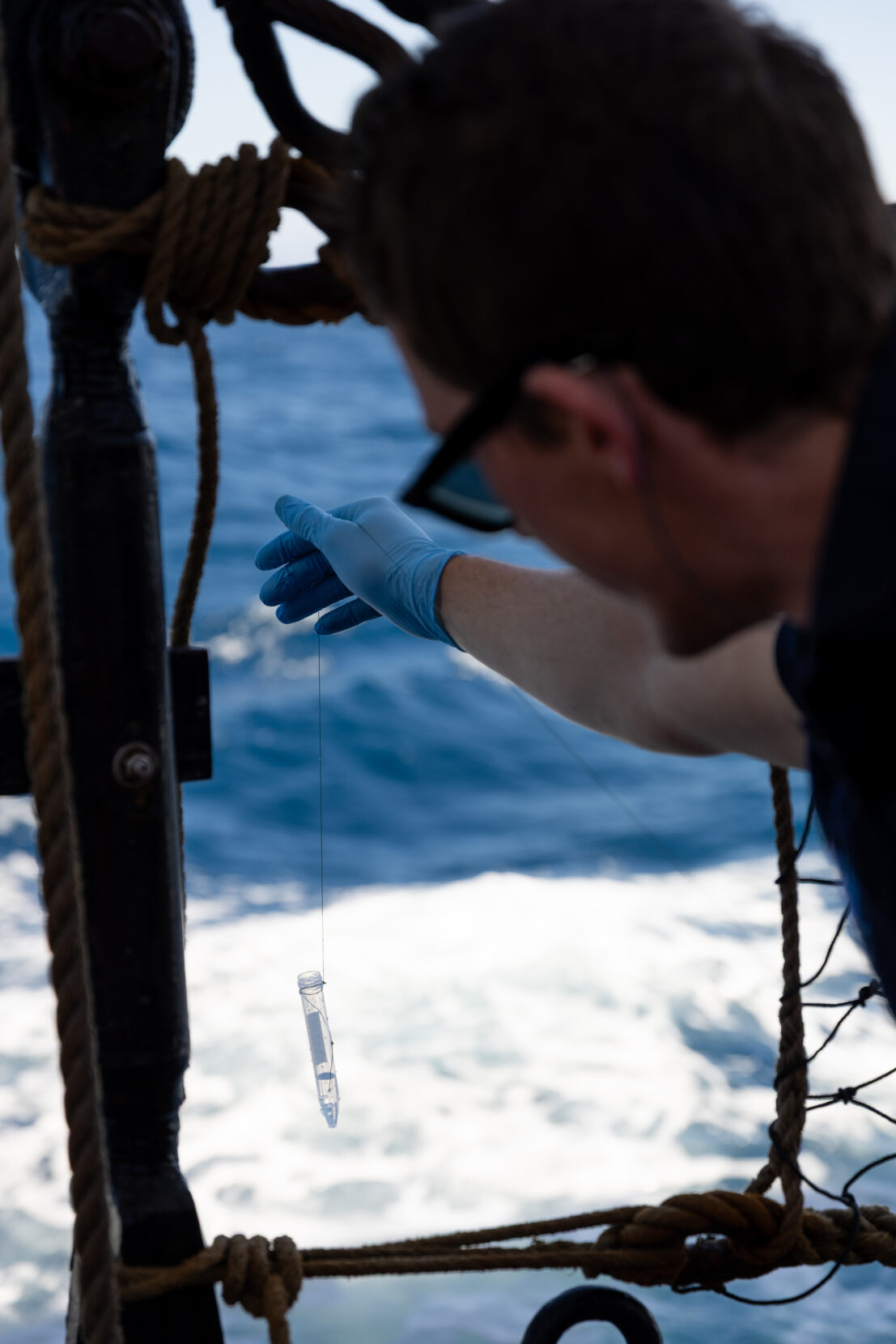

At multiple parts of our voyage leg, the resident researcher sent by the Explorers Club unlatched a gigantic case on deck. He wrapped a small plastic vial to the end of a few meters of clear fishing twine, cautiously leaned over the low edge of the ship, and tossed the plastic over the edge of the boat into the waves.

A moment was spent in anxiety, hoping that the knot held true, until it was reeled back on deck. Those inches of water collected would be added to the global eDNA study, the water sample to be pressed through a centrifuge, filtering out the jumble of DNA — left from shedding scales, waste, and other cells — of every organism that had passed through.

When collected at a global scale, on a two-year voyage across three major oceans, it could illuminate how migration might be changing or alert us that a new or rare species was present in the water. Around New Zealand, I held out hope that our little samples might pick up a hint of DNA from a spade tooth whale, thought to be the world’s rarest whale species. We’ve found seven of these whales in history, but only observed them when they’re dead, washed up on beaches.

With eDNA, we can see that each drop of water has memories.

A researcher on board the Darwin200 expedition dangles a plastic vial into the ocean to collect a water sample for a global eDNA study. Photo: Jordan Winters.

~~

As the Beagle approached Cape Horn on October 24, 1832, Darwin got a front-row seat to a bioluminescent light show:

“The night was pitch dark, with a fresh breeze. The sea from its extreme luminousness presented a wonderful and most beautiful appearance; every part of the water, which by day is seen as foam, glowed with a pale light. The vessel drove before her bows two billows of liquid phosphorus, and in her wake was a milky train. As far as the eye reached, the crest of every wave was bright; and from the reflected light, the sky just above the horizon was not so utterly dark as the rest of the Heavens. It was impossible to behold this plain of matter as it were melted and consuming by heat without being reminded of [John] Milton’s description of the regions of Chaos and Anarchy.”

In the same way that Darwin was a voice in my ear, the 17th-century poet was whispering in Darwin’s. During his voyage on the Beagle, on excursions when he could only carry a single volume, he chose Milton, carrying the epic poem across continents and oceans.

The poet’s impact is obvious in Darwin’s second titular work, The Descent of Man. But in the moment that he watches bioluminescence, I read a man opening his eyes to the beauty in the madness that is nature outside of the Garden of Eden. In the way that I see spirals of Fibonacci in the tumbling of salps, Darwin grasps that God’s hand may not be that of a tender gardener — but a mad scientist whose magic turns a microscope into a kaleidoscope.

~~

The Beagle had twice as many people in half the space of the Oosterschelde. And yet, Darwin wrote next to nothing about life on board except for complaints of the two feet of headroom above his hammock. I joked that Darwin would have been insufferable as a bunkmate, at a minimum, for the morbid collection of dead birds he kept in a locker and his jars of octopus and fish.

While Darwin was a low thrum in the back like a bass line, the day-to-day of ship life had a demanding melody. The meticulous folding of sails into neat fans that were then rolled bonded us as a team. We’d bicker over crease crispness and packing strategies, then high-five when we finally tucked the layers of polyester away. I washed dishes until I knew the weight of the breakfast forks over the dinner knives without looking. We each took turns reading the instruments and learning to helm.

Passengers take a turn at managing the sails aboard the Oosterschelde. Photo: Jordan Winters.

Between those tasks, we formed our little cliques. I ate up my roommate Melanie’s stories of being in the Royal Air Force, I swapped books and science fiction with Euan and his father Andrew, and my fondness for the wit and charisma of the researcher Riley blossomed into a crush. In those moments, I left Darwin in the past.

~~

Occasionally, I’d find my daydreaming broken by the fluttering call of someone asking, “Grant? Where is Grant?”

Our resident ornithologist, Grant Terrell, his ice blue eyes always wide with excitement, was keeping up a global sea bird count — with nothing but a pair of binoculars and a camera. I spent hours with him, discussing our niche fascinations with tussock grass and oarfish like two kids under a pillow fort.

We understand so little about a sea bird’s life away from shore, and with his observations, we’ll understand how the populations are doing, where they’re migrating, and will raise the alarm if anything is unusual. On my leg of the expedition alone, we observed more than 37 species.

After a couple of hazy evenings, we finally got a clear sunset. I squinted at the bright periphery, hoping that I would see a green flash. Legend says that the rare phenomenon signifies a soul returning from the dead.

~~

Barometric pressure built up for the next two days. Our bunks began to smell not of brine but of wind and sunshine. One by one, high-tech overalls with reflectors made an entrance. The bright color would give its wearer a chance if they went overboard.

The waves shifted direction from bow to stern instead of broadside. We were no longer on a pendulum. In my journal, I began to tire of trying to detail waves getting bigger when they were already a punishing 10-to-12 feet. Comparing them to one- or even two-story buildings couldn’t capture the fallout.

The Beagle voyage was the first time the Beaufort wind scale was used for wind observation, which we use when we say things like “hurricane force.” The Oosterschelde flirted with gale force.

~~

I knew something was wrong when I started falling sideways, straight into the wall. Before I could even groan in pain, gravity shifted again, this time, threatening to send me hurtling off my perch in the top bunk. Adrenaline kicked in as I clawed at the wall that I just cracked my head on and squeezed any muscle that would obey my groggy brain. I exhaled as the walls again became inanimate. I winced as fresh bruises throbbed under my skin.

“I hate every wave of the ocean, with a fervor, which you, who have only seen the green waters of the shore, can never understand.”

It was 3:30 am. In the absence of sleep, it was time to search for the specter that had so rudely awoken me.

I dressed, which didn’t take long because I was sleeping in my only clean clothes, and laced up a pair of wet boots. I shuffled along dark halls and up a flight of stairs to throw open the door and face the source of my abuse.

We had officially entered the “Roaring 40s” — the nickname for latitudes between 40 and 50 degrees. It’s a taste of what lies beyond in the Southern Ocean, the doorstep to Antarctica, which Russian ships had first spotted only 11 years before Darwin stepped onto the Beagle. For the first time, I became genuinely fearful. I returned to safety below.

A chair, or maybe a side table, crashed on the deck above me, and I stifled a scream. The beams made sounds I’d never heard wood or metal make. It wasn’t bending or stretching, but a constant shriek, as if in pain. In my head Milton and Darwin began laughing, egging each other on: “What hath night to do with sleep?” Milton asks and Darwin replies: “Oh a ship is a true pandemonium.”

I ground my teeth so hard, I worried I was going to chip a tooth. Hours passed like this.

There in the darkness, I became embroiled in a fever dream.

~~

The Oosterschelde navigates the roiling waves of the Tasman Sea. Photo: Jordan Winters.

Darwin is often heralded for his anti-slavery stance. In his diaries, though, a more complex picture forms around his view of non-Europeans. Even before Descent of Man, in which Darwin explores humanity’s own natural selection, he waded into the muddy business of ranking races, particularly the Maori, whom he called “savages” in his journals.

“If the state in which the Fuegians live should be fixed on as zero in the scale of governments I am afraid New Zealand would rank but a few degrees higher, while Tahiti, even as when first discovered, would occupy a respectable position,” he wrote.

He said a lot about the Fuegians from his thousand-foot perch as an academic but wrote nothing of the four kidnapped Fuegians living on board. The only female aboard the Beagle, Yokcushlu, was a kidnapped nine-year-old. His paternalistic sympathies were as inconsistent as his justification of violence against Indigenous people in South America:

“Everyone here is fully convinced that this is the most just war, because it is against barbarians. Who would believe in this age that such atrocities could be committed in a Christian civilized country?”

He went on to reassure himself, “The children of the Indians are saved, to be sold or given away as servants, or rather slaves for as long a time as the owners can make them believe themselves slaves; but I believe in their treatment there is little to complain of.”

I continued to thrash against wood, then metal, then wood again as I confronted reality: A man who I wanted desperately to connect with — who I had tried to carry with me — may not have seen me as an equal.

~~

Day six: We should have made landfall but didn’t. We cranked on the engine, but the currents forced us backwards. For our safety, everyone except the permanent crew members had been sequestered inside. I counted skylights to pass the time.

The weather was still so bad around the port of Bluff, New Zealand, we were not allowed to moor at the dock. We found our own sheltered anchorage. Unlike when you approach land from the sky, this vantage point forces you to meet the cliff and the mountain on their own terms. Where you don’t have the upper hand. Where the perspective keeps shifting, and land appears as dynamic as the sea.

Land was so close, but we could not touch it. Light came in cold shafts between gray slates of clouds. We were stationary for the first time in over 170 hours. The wind whistled at a higher pitch through the shrouds, the frequency of a low-lying headache reduced to a simmer. Thoughts became slightly clearer.

~~

A crew member of the Darwin200 expedition checks the tall ship’s lines from high in the air. Photo: Jordan Winters.

We crawled up the southeastern coast, and I watched sheer, multicolored cliffs and counted sheep on rolling green hills. On Christmas Eve, we found a secluded cove and the sun poked out. It wasn’t really warm enough to jump in the water, but a few of us did it anyway. I climbed up some of the rigging and plunged into the sea face-first.

I hit the water hard. There had been so much focus on not going overboard that I felt out of my element in the blue. I surfaced and realized the current was strong. But I caught my breath and leaned into the discomfort.

I pressed my hand to the hull of the Oosterschelde.

The ship and the sea have met many times in past lives, and each time with a different face, as new beings.

It’s likely that no plank is the same one that was put in place when she first set sail more than a century ago. Every rope and plank, grown by once-living things, breathes life into the ship. A boat does not protest when the time comes to pull out the planks that no longer serve the mission.

I wasn’t Darwin’s vessel, nor his host or shipmate. I quietly reconsidered my accusations of his spirit. My directive was to treat his legacy with the same tough tenderness given to a boat.

~~

From the water, I looked up at the netting of my favorite perch, squinting at the platform above and envisioning a high-dive off. I bobbed my head under the water, the cold a balm to my fear. I felt a sensation around my navel, something sweeter than an ache.

When astronauts go into space and see Earth for the first time from their spaceship, they experience something called the “overview effect.” Author Frank White was the first to describe this phenomenon as “… a message from the universe to humanity. The message is that the Earth, when seen from orbit or the moon, is a whole system, where borders and boundaries disappear, and everything is interconnected.”

This profound experience is said to scratch a particular neurological itch and rewire brains in the process. More recently, sailors have coined our own term — “the oceanview effect” — to describe the ethereal feeling of days and weeks out of sight of land.

I calm my racing heart and face the uncatchable wind that has gathered across thousands of miles.

A bittersweetness, something like déjà vu, washed over me as I looked up at my own rocket ship. The wisps of the paradoxes of the oceanview effect began sinking in — that the ocean and universe was expanding as I was shrinking. It’s the odd trick the brain plays on divers who get claustrophobic when confronted with the wide deep.

Darwin’s spirit of exploration had gotten me here, just as Milton had opened up new avenues of thought for him. Because of Darwin, I can thank some ancient ancestor for my ability to tread water. Hearing the conch shell-song in my lungs, though — that’s between me and the ocean.

Suspended over the Tasman Sea, the author pauses from her documentarian duties to recline in the whisker netting of the Oosterschelde. Photo: Jordan Winters.

Jordan Winters

Jordan Winters is essentially an aspiring pirate (the fun kind).