Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

At the western edges of North and South Dakota, large swaths of grassland prairie collide abruptly with multicolored rock formations of limestone, shale, volcanic ash, and sandstone. When seismic upheaval created the Rocky Mountains 65 million years ago, these Dakota badlands formed almost as an afterthought, as sand, silt, and mud flowed down ancient rivers to be deposited here, hundreds of miles away.

I hoisted myself over the rocks and dusty buttes of the Caprock Coulee Trail in Theodore Roosevelt National Park. Being stripped so honest and bare lends a certain beauty to these 110 square miles of protected land.

Sweat pouring down my brow, I welcomed the chilly gust of the autumn wind. Peak fall color ended weeks ago, so most of the cottonwoods had lost their golden leaves. But closer to the ground, a few fading goldenrod and Indian paintbrush plants managed to hold onto their last wilted blooms.

I could see Roosevelt shaking the powder from his spectacles, pounding his thick chest as the crisp mountain air filled his lungs, and exclaiming the majesty of the park.

With the sun dropping lower and lower in the west, I tried to walk with purpose, but found myself all too frequently stopping to take in the views. The vistas are so open and vast, you can see anyone, or, more appropriately, the absence of anyone, for miles. Other than a solitary golden eagle flying overhead, I was completely and totally alone.

I imagined my dad in his recliner and wished he were with me on the trail.

~~

A few days earlier, I stepped out of my camper van in Medora, North Dakota, a tiny town where you can walk past nearly every little cottage and souvenir shop in less time than it would take to grill a medium-rare steak. I imagined the town didn’t look much different 136 years before, when a 26-year-old Teddy Roosevelt arrived via a Northern Pacific steam train.

When Roosevelt first came to the Dakotas, he came to hunt buffalo and other big game. Bison once roamed these Great Plains by the millions. The herds were so massive — stretching miles in every direction — that they would take days just to pass through an area. The echo of their hooves must have reverberated throughout the West.

But by the 1880s, the species had been all but exterminated, in part because of a heartbreakingly effective plan to starve the Lakota people and force them off their land. Where the buffalo once roamed free on the plains, white settlers raised cattle that would be bought, sold, and eventually meet their end in an industrial slaughterhouse. Roosevelt bought stakes in two of those ranching operations, determined to remake himself into a frontiersman like his boyhood heroes Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone.

But more than reinvention, Roosevelt sought solace. Both his wife and mother had died within hours of each other earlier that year, and a devastated Roosevelt sought to wrap himself in the “desolate, grim beauty” of the Badlands.

I came for similar reasons.

In 2016, Congress passed legislation proclaiming the bison as the U.S.’s first national mammal — more than a century after the species teetered on the brink of extinction. Photo: Sivani Babu.

~~

My first night in Medora, I boondocked just outside of town, on a cliffside dirt plot in the Little Missouri National Grassland. As the sun fell and I finished my dinner of rice and beans, I watched the light transform the Badlands foothills stretching out below me.

In this soft glow, subtle shades of sediment, obscured earlier by the brilliance of day, emerged from the shadows.

When I was in elementary school, I begged my dad to go camping. When he finally relented, the two of us headed to a rural Indiana county park, not far from home. I was thrilled with anticipation. Would I see a bear? Would we climb a mountain?

It could be considered the most important camping trip in world history — at least in my view of it.

We pulled into a spot and set up our two-person pup tent. It was evening, and we cooked hot dogs over a roaring campfire on sticks plucked from the woods. Although we had Cokes in glass bottles chilling in a Styrofoam cooler, I only wanted to drink the lukewarm water in my Cub Scout canteen, just like a real outdoorsman.

We had just bedded down for the night when the coughing started. I was prone to coughing fits in my youth, but this was a particularly bad episode. Maybe it was the smoke from the campfire or perhaps the cool night air. Minutes went by. Both our faces began to redden, but for different reasons. Tears welled up in the corners of my eyes.

“Stop coughing,” Dad ordered, infuriated, but my inflamed lungs refused to listen. Many profanities ensued.

“Do you want to go home?” he bellowed.

The tears flowed harder and faster. I meekly whispered yes. I sat in the Ford Bronco passenger seat as Dad ripped the tent from the ground, heaving the ball of nylon, aluminum poles, and plastic stakes into the back. By the time we reached home, the coughing fit was finally over, but I couldn’t stop crying.

We didn’t attempt another camping trip together for nearly a decade.

~~

In the third grade, I wrote a book report about Teddy Roosevelt and became obsessed. I read and re-read Roosevelt’s entry in our home encyclopedia and checked out books about him from my local library. In Roosevelt, who had struggled with asthma but found strength and freedom in the outdoors, I had found a kindred spirit — and perhaps more importantly, a role model I couldn’t disappoint.

As the years wore on, I couldn’t help but draw comparisons between the adult Roosevelt and my father. Both were physically strong men, with weak eyes, quick tempers, and gruff personalities. Both were combat veterans; Roosevelt famously led the Rough Riders, while Dad earned multiple service medals serving with the Army’s 69th Engineer Battalion.

Both men, I would come to realize, were also products of their times.

~~

Scattered throughout the park remain … remnants from this long-ago past, like cairns pointing the way toward forgotten moments in time.

Above my desk hangs a postcard of Roosevelt standing on Yosemite National Park’s Glacier Point. On the back is a note I wrote Dad on my most recent visit to the park. Before my trip, we had gotten in a huge fight and hadn’t spoken to each other in weeks. On the card, I wished him well and suggested we talk when I got back.

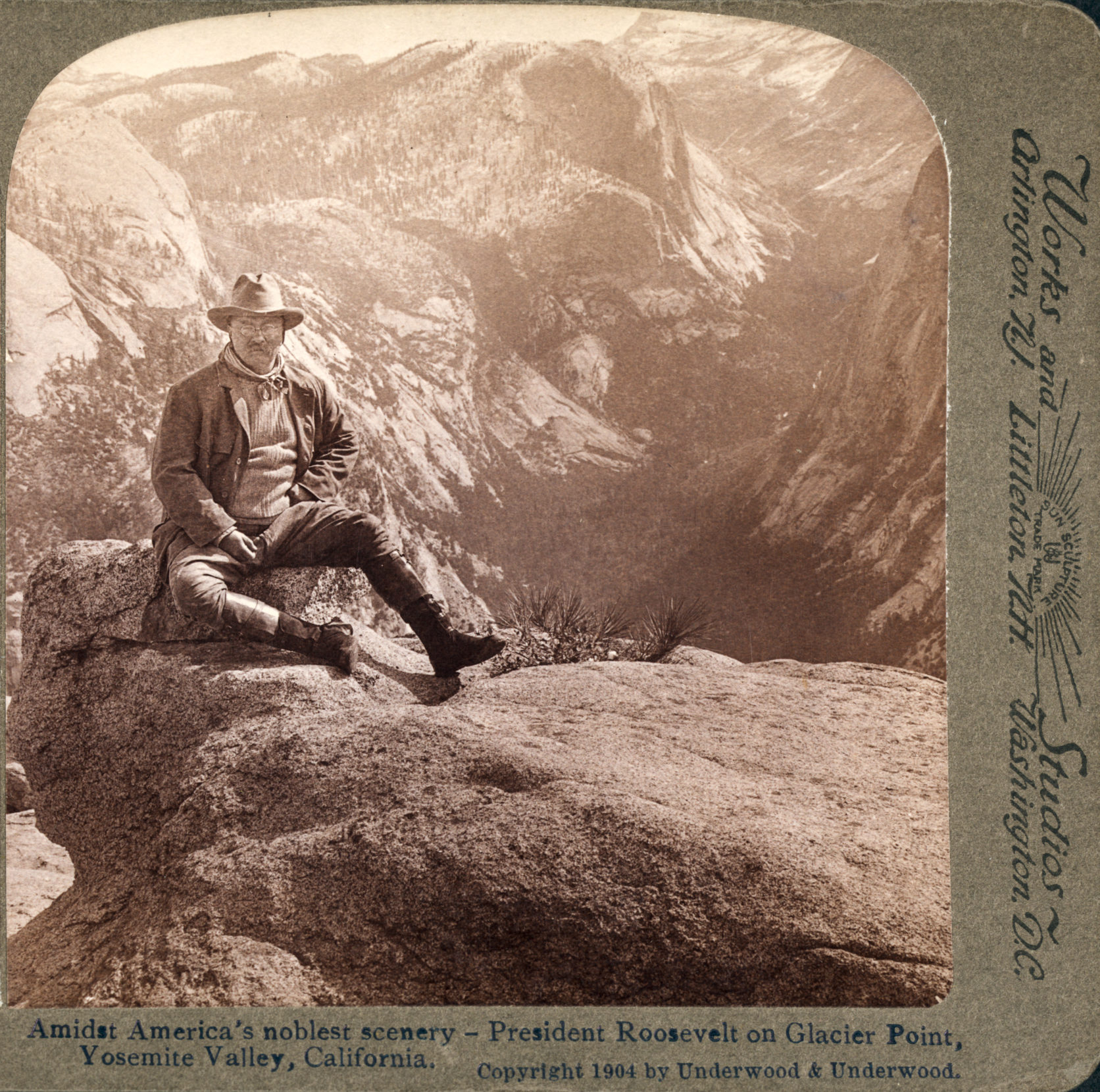

In 1903, more than a century before I bought that postcard, a blizzard hit Yosemite, cloaking the ground and forest in layers of soft white. A 44-year-old Roosevelt had slept on a bed of boughs under a silver fir near Glacier Point, covered in nearly five inches of new snow. Nearby, the famed naturalist John Muir dozed atop his own nest of tree branches, protected from the elements by only a simple piece of long cloth.

The first time I read about this story, I could see Roosevelt shaking the powder from his spectacles, pounding his thick chest as the crisp mountain air filled his lungs, and exclaiming the majesty of the park. I’d like to think it was at that moment President Roosevelt resigned himself to doing whatever he could to protect the park and other places like it. It could be considered the most important camping trip in world history — at least in my view of it.

“I do not want anyone with me but you,” Roosevelt wrote to Muir in advance of the trip. “I want to drop politics absolutely for four days and just be out in the open with you.”

For three days, the pair took in Mariposa Grove, El Capitan, and Bridalveil Fall, and hobnobbed with the artist Thomas Hill at his Yosemite studio. A photographer snapped a photo of the men at Glacier Point, overlooking the gorgeous valley below. Muir took every opportunity to remind Roosevelt of the need to further protect the land.

That first night, they camped under massive sequoias — “the enormous cinnamon-colored trunks rising about us like the columns of a vaster and more beautiful cathedral than was ever conceived by any human architect,” Roosevelt wrote afterward. Before drifting to sleep on a pile of 40 wool blankets that had been laid out by his men, the president asked about the thrushes “singing beautifully in the solemn evening stillness,” but to his surprise, Muir knew nothing about them.

Despite championing exploited lands like those of Yosemite Valley, there was a lot that Muir would overlook — including the people who had lived there hundreds or thousands of years before white settlers.

Roosevelt was enthralled both by Yosemite’s astonishing beauty and Muir’s immense passion for nature. Although the president was already a staunch supporter of conservation, after the trip he redoubled his efforts to protect America’s most precious land. During his terms in the White House, he set aside more than 230 million acres of land to create national parks, forests, refuges, and more. No president had ever done more to protect wildlife and public land.

President Theodore Roosevelt poses at Glacier Point during his famed 1903 visit to Yosemite. Photo: Underwood & Underwood/Library of Congress.

~~

In Theodore Roosevelt National Park, jagged and gnarled knolls stand, often precariously, over this landscape that was methodically eroded away by the wind and water that created them eons ago.

As Roosevelt himself described the multihued formations, they “seem hardly properly to belong to this earth.”

But there’s another part of the landscape that, while less spectacular than the swirling colors and contorted hoodoos of the mountains, adds depth.

Before there were buttes and grasslands here, gigantic bald cypress trees towered over a vast swamp. Scattered throughout the park remain hunks of petrified wood — remnants from this long-ago past, like cairns pointing the way toward forgotten moments in time.

~~

When I was seven or eight years old, I met another boy about my same age who was staying with family down the street. Four decades later, I can still see his face — wavy hair, light-brown skin, huge smile — but for the life of me, I can’t remember his name. We were playing catch in my backyard when my mom came out and said he had to leave: Dad would be coming home soon. This happened a few times that summer. One day, Dad came home early. I didn’t see my friend much after that.

As I got older, I began to understand why. My dad came of age in a small Indiana town in the 1950s and 60s. Bigotry and racism were the norm. Not much had changed by the time I grew up there decades later.

Eventually, I moved away, first to college, then to the East Coast for a while. The larger world opened my eyes.

When I fell in love with Dee, I was nervous about introducing her to my parents, in large part because she was born in Korea. As far as I knew, Dad’s only experience with Asian people was shooting at them during the Vietnam War. Although I’d steeled myself for a fight, he seemed genuinely happy for us. It wasn’t long before he was more fond of her than me.

In the ensuing years, Dee and I tried to expand Dad’s horizons — introducing him to our friends of various hues and backgrounds as well as exotic (to him) restaurants. He seemed to enjoy red curry and mousakka, although sushi would remain a bridge too far. Over dinner or a beer (always Budweiser), I spun stories of my most recent travels, talking about the Japanese bluegrass band I’d met in Tokyo or the Cuban cycling team I rode with outside of Havana.

Over time, he stopped asking about my safety and seemed to understand how I saw the world, as a beautiful and friendly place. I stopped worrying about how he’d react in certain company.

It sounds foolish, but for a time, we thought we’d done the impossible: cured his racism.

~~

On the Caprock Coulee Trail, I grabbed onto boulders to help myself upward, my sweaty palms collecting a thin layer of dust and debris — a reminder of the erosion that continued to shift the ground under my feet.

For years, Theodore Roosevelt had been a two-dimensional figure to me, living only in books, sepia-toned photographs, and my imagination. Thinking of him hiking up Adirondack mountains or exploring the Amazon post-presidency fit right into the perimeters I had blocked out for him. Harder for me to place were other moments from Roosevelt’s life — some so abhorrent they make my skin crawl.

In 1892, Roosevelt took the lectern at Boston’s Lowell Institute as a 34-year-old politician rising in prominence on the national stage.

“This continent had to be won,” Roosevelt railed in a speech defending the government’s treatment of Native Americans, prodding the podium for emphasis. “We need not waste our time in dealing with any sentimentalist who believes that, on account of any abstract principle, it would have been right to leave this continent to the domain, the hunting ground of squalid savages. It had to be taken by the white race.”

No president had ever done more to protect wildlife and public land.

When it came to race and nationality, “Roosevelt was a paradox,” according to historian Clay Jenkinson, whom I spoke to after my trip. “He was ahead of his time in so many ways, but also solidly of his time in others.”

Roosevelt held a common belief at the time that suggested white people were culturally superior, and others needed to catch up. According to Jenkinson, Roosevelt believed the government needed to do “horrible, dirty, and uncivil” acts to both civilize and wrest control of the continent.

Those 230 million acres of land Roosevelt set aside for the public good? This was made possible by the coerced displacement of Native Americans, often in blatant violation of existing treaties, through the Indian allotment system that he supported. The “pristine wilderness” celebrated in these public lands ignored their ancestral history.

As president, Roosevelt also turned a blind eye to the enactment of Jim Crow laws and did little to stop the rampant lynchings throughout the South. He also believed “the great majority of Negroes in the South [were] wholly unfit” to vote, and affording them that right would “reduce parts of the South to the level of Haiti.”

Yet in 1901, a month after he was inaugurated, Roosevelt invited famed Black leader Booker T. Washington to dinner. It was a monumental occasion; this would be the first time a Black man would share a meal with a sitting president at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave.

Below the surface, however, that monumental meeting was a relatively safe one for Roosevelt: Washington was an advocate for the Atlanta Compromise, arguing that Black people should work hard in lower-level occupations and slowly earn respect from whites. Equal rights would come as Black people proved to be capable citizens. Until that time, they needed to quietly endure the indignities imposed upon them. This approach aligned with Roosevelt’s own views and beliefs — and would help boost his party’s political prospects in the South.

The more I learned, the more disgusted I became. Why hadn’t I known about any of this? But then, I must admit I hadn’t scratched below the surface of Roosevelt’s eco-champion myth. Leaving his legacy intact preserved him as that flawless icon of my youth.

At once bathed in a golden glow and receded into shadow, the sweeping vistas of Theodore Roosevelt National Park are rich in depth. Photo: Sivani Babu.

~~

In the park’s nearly deserted Cottonwood Campground, overlooking a meadow and the Little Missouri River, I only had my thoughts and the occasional passing bison for company.

The echo of their hooves must have reverberated throughout the West.

Sitting in a camp chair, whiskey in hand and trying to make out the Milky Way in the night sky, I thought again of my dad and his recliner — the one that he used to sink his exhausted body into after long days at the local meatpacking facility.

Looking back, I can see that Dad grappled with the weight of fatherhood. Nearly every decision he made was to better provide for our family, including pushing aside his dreams of becoming a draftsman or furniture builder for the security of a full-time job. Sometimes his frustration surfaced in bouts of bitterness, but more often he’d muster the energy to play catch in the yard or take me fishing on the banks of the Wabash River.

In 2013, after spending nearly his entire life in that same community where we both grew up, Dad moved to my new hometown of Indianapolis. Immediately, he integrated into my life. He threw himself into a phase of fatherhood more comfortable for him — insisting on driving me to the airport, no matter the hour; looking after our house and cats when Dee and I left on vacation; there to hold a ladder or help with any household task.

Last winter, a few weeks before I set off to photograph the northern lights in Alaska, Dad mentioned, seemingly out of the blue, that he wanted to tag along. While I was tickled at the thought of his company, I was going to be spending hours in minus-20-degree cold and hiking in knee-deep snow in the dead of night. His arthritis-ravaged body wouldn’t allow him to do any of it, so I put him off. It was so unlike him to even consider joining me on such a trip.

I should have realized then that something was amiss.

While I was in Alaska, COVID-19 cases began to spike across the globe. My connecting flight was in Seattle, then one of the U.S. epicenters of the pandemic. I told Dad not to pick me up from the airport, but he insisted. I relented, not realizing the severity of the situation. Less than a week after I returned from my northern lights trip, the lockdown began. I texted Dad daily, until he stopped responding. I didn’t think much about it for a day or two, until my sister called, asking if I’d heard from him.

I drove over, pulse racing, and found Dad in his recliner, where he’d peacefully passed away the night before. For months, I couldn’t shake the fear that I had been an asymptomatic carrier and was personally responsible for his death.

~~

Before reaching North Dakota, I explored its sister state to the south. For much of my drive, a Ned Beatty-like squeal had emanated from underneath the hood, the telltale sound of a serpentine belt at its breaking point. A few hundred yards away from the entrance to Mount Rushmore National Memorial, I heard a loud bang, and the smell of scorched antifreeze quickly filled my nostrils. Power steering gone, I had to muscle the multiton van into the parking lot.

While waiting for the tow truck, I stretched my legs on the short Presidential Trail, snapping a few photos of the monument framed by golden foliage.

Intellectually, I know the problems with Mount Rushmore, starting with the desecration of a 1.8-billion-year-old mountain called the Six Grandfathers (Tȟuŋkášila Šákpe) in the Black Hills, considered the center of the Lakota universe. Then there are the myriad flaws of the men carved into the granite.

Amid a weird cauldron of pride, remorse, and uncertainty overflowing in my gut, I considered the good and the bad — the incredible accomplishments of these presidents, the government’s betrayal of the people who claim this land as sacred. A part of me, I’m ashamed to admit, was still thrilled to look up at my boyhood hero’s 60-foot face in person.

Leaving his legacy intact preserved him as that flawless icon of my youth.

I passed the postcards and plastic trinkets in the visitor center and headed to the Sculptor’s Studio. Outside the vaulted room, where exposed wood rafters frame a 1/12 scale model of Mount Rushmore, I joined a ranger talk promising a lesser-known side of Mount Rushmore’s origin story.

Community leaders had planned on creating a tourist attraction featuring both white and Native American heroes of the West carved into the nearby granite pillars known as the Needles. But sculptor Gutzon Borglum had hijacked that idea and instead created a massive monument to manifest destiny and American greatness on Mount Rushmore’s more stable granite bluff. As the ranger told the story, Borglum was equal parts visionary artist and wacky con man.

I kept waiting for her to mention Borglum’s alleged involvement with the Ku Klux Klan, but his racism was only alluded to tangentially. She briefly referenced the land battle between the Lakota and the American government, one that continues to this day, but merely as a segue to other subjects.

After her talk concluded and the crowd dispersed, I stuck around to ask the ranger why she didn’t delve into more detail about the Lakota people. She assured me that the park service frequently brings in tribe members to recount the tragedies surrounding Rushmore’s creation. They were the true experts, she said, and could tell their story with greater understanding and more eloquently than she could.

As we chatted, she mentioned she’d grown up in the area, and her pride in the memorial was evident. The more questions I asked, the more her tone grew defensive. Despite their shortcomings or prejudices, she stood firm in her belief — that we can’t judge Roosevelt or others by today’s standards.

But what does it mean to glorify a story written in stone — both for the three million people that travel here each year as well as for the institution that story idolizes?

Despite the ranger’s admonition, I was determined to reconcile my idealized versions of these two giants of my childhood with the men they actually were. Was I willing to put my dad under the same scrutiny I was giving Roosevelt? Would it be hypocritical not to?

The sun casts a dramatic spotlight on the carved faces of Mount Rushmore. Photo: Cultura Creative RF/Alamy.

~~

Back home in Indiana, I reached out to Ashley Nichole Lewis, a professional fishing guide and member of the Quinault Indian Nation tribe. A friend of mine recommended we chat, raving about Lewis’s historical insights, not to mention her abilities to hook a trout. Being an outdoorswoman, she had an obvious connection to nature, but I was stunned by how much our perspectives differed.

Where the national parks had always brought me comfort and inspiration, Lewis saw them as way for the U.S. government “to erase the violence against Native Americans.”

“If we want to heal and move forward as a truly united nation, white Americans are going to have to face some hard truths,” she said. “What Roosevelt called ‘conservation’ is a dirty word for many Native people — meaning their land was stolen, their food and resources taken away.”

Our public lands had long felt to me like a moral good, but it was always people who look like me dictating what that meant. For true healing to begin, Lewis said with conviction, a reconciliation must take place.

“It’s difficult to grapple with,” she said, “especially for people who have a deep and profound respect for our national parks, nature, and the environment. But it is possible to still appreciate those things and acknowledge the real history.”

As I considered the tattoo of the National Park Service’s famed arrowhead logo on my left leg, her next point hit even closer to home: “Poking holes in the myth of Theodore Roosevelt, in many ways, pokes holes into our identities as Americans.”

And, in a way, as sons.

~~

Jagged and gnarled knolls stand, often precariously, over this landscape that was methodically eroded away by the wind and water that created them eons ago.

Before I left Theodore Roosevelt National Park, I watched a small bison herd lazing in a meadow. Dozens milled about, some grazing on bits of grass, others laying in the dirt, taking a break from the midday sun. Two big males snorted and sparred, presumably over a female standing nearby.

After nearly being exterminated more than a century ago, bison continue to repopulate. In fact, there are more buffalo now than when Roosevelt first came to the Dakota territories in 1883.

Despite the promise in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal,” racism remains a foundational layer upon which our battles continue to be fought. Days before Donald Trump left the White House, his administration released “The 1776 Report,” a propaganda guide whitewashing slavery and promoting white supremacist rhetoric. Today, attempts to manipulate which version of history is told remain pervasive — whether it’s pushback against making Juneteenth a national holiday or pundits redefining critical race theory as a cultural war cry.

Certain changes, whether in society or in nature, face stronger resistance than others. The badlands offer topographical proof, with its jumble of rocks eroded into fantastical shapes — from the durable, red, bricklike butte tops to the crumbly, popcorn-like bentonite clays below.

Granite faces, I had learned on my visit to Mount Rushmore, hold their form against all sorts of forces, with an extremely slow erosion rate of an inch or so every 10,000 years.

Carving the Rushmore images “was a mistake,” Jenkinson had told me, “but the damage is done. It’s a beloved site for millions of Americans. The only thing that can realistically be done is to change how we interpret and present [this history]. We know what Rushmore meant in 1940, but what does it mean now? What will it mean in 2040 and beyond?”

Roosevelt didn’t turn out to be the man I had idolized as a third grader. Luckily, my dad didn’t stay the same as the gruff patriarch I knew then, either.

Despite his flaws, I truly loved my dad. I don’t have to ignore or forgive his darker aspects for that to remain true. He made a lot of progress in his final decade or so; who knows what would have happened if he lived another 10 years? I wish we could have found out.

Dad suffered from a series of heart conditions in the latter half of his life — a consequence, I had joked, of having too big a heart or no heart at all, depending on the day. Later, I learned that he’d recently been told his condition had worsened. He had been living on borrowed time.

I didn’t infect Dad with COVID-19 and kill him. Ultimately, his biases weren’t my responsibility, either. But I am responsible for how I honor his memory, and maybe the best way to do that is to identify and avoid his mistakes.

Each of us is created by our own seismic upheavals, starting with a foundation of lessons taught to us by our parents, then built upward by our own experiences. Over time, life wears away and reshapes the raw material. Some parts get buried; others wash away. The changes don’t come easily, but taken together, the result is nothing short of majestic.

The changing light illuminates the undulations of the Dakota badlands in Theodore Roosevelt National Park. Photo: Michele Falzone/Alamy.

Robert Annis

After spending nearly a decade as a reporter for a major metropolitan newspaper, Robert Annis finally broke free of the shackles of gainful employment and now freelances full-time, specializing in outdoor-travel journalism.