Support Hidden Compass

Our articles are crafted by humans (not generative AI). Support Team Human with a contribution!

We’re coasting across the gulf when a distant, wiry fisherman stands up in a cayuco, a narrow dugout canoe. The heat beads sweat into my eyes; the equatorial sun splinters over the tranquil waves. Our guide, Degimalo Andup, a thickset, middle-aged man native to these islands, cuts the motor on our dinghy. The shallow sea around us, the “grandmother” of Degimalo’s people, coruscates in lustrous shades of turquoise.

I’m hopscotching among these idyllic islands of Guna Yala, in an area formerly known as the San Blas archipelago. Most of these 365 islets are nothing more than a cluster of palms ringed by white sand — they’re deemed an island if they have at least one coconut tree. The Guna inhabit approximately 40 of these islands off the coast of Panama.

Isla Hierba, one of 365 islets in Guna Yala off the coast of Panama, of which merely 40 are inhabited. Photo: Wilfrid Cross

Balancing in our wake, the fisherman casts a handline — a thin rope with a hook on the end — into the water. No more than a minute or two passes before he muscles up the line, coiling it around his forearm.

He’s snagged a four-and-a-half-foot barracuda, razorlike teeth bulging from its jaws. Degimalo, sensing an opportunity, steers over to the dugout. The two boatmen haggle in their native language of Dulegaya. Degimalo passes the fisherman money, then hoists up the barracuda by the gills. He heaves the flailing fish into a bucket to spit-roast later for dinner.

The Guna people were the first indigenous group in Latin America to gain sovereignty. When Panama, backed by U.S. interests eyeing canal-building ventures, seceded from Colombia in 1903, the newly installed Panamanian junta pressured the Guna to westernize and assimilate. Panama hoped to locate police in the archipelago to patrol its border with Colombia, but the Guna resisted. Guna leaders orchestrated attacks on the junta’s forces during the San Blas Revolution in February 1925, declaring their own independent Republic of Tule. Eventually, the U.S. sent in a warship to help broker a deal in the standoff between the Panamanian government and the Guna representatives.

Today, the Guna control a comarca, an autonomous zone similar to a reservation, including a strip of dense jungle along the shore and this scattering of islands tucked away in a tranquil gulf on the Atlantic edge of Panama.

This may be our last chance to see the area. Within a decade or two — or as soon as the next major hurricane strikes — these islands are expected to vanish, displacing the 45,000 Guna who call them home.

How, I wonder, will they cope?

~~

The first island I step foot on is Gardi Sugdub. It’s approximately the size of a large city block, and, with a population of more than a thousand, it’s nearly as dense as Manhattan. Thatch-palm, cane-stick, dirt-floor huts with plywood or tin roofs rub shoulder to shoulder, three stories high. Every inch of the island is built up, right out to the clapboard docks. Without a waste collection system, rubbish crowds the narrow muddy paths, which are redolent with a faint odor of sewage.

I wander the streets through wide-open doorways and cramped courtyards — the whole island is a ramshackle maze. The bunched-up, open-air construction baffles notions of inside and outside. I accidentally meander into someone’s living room. Suddenly, I’m standing between a couple of kids sprawled on their couch and a grandmother chattering at them. They barely glance at me, accustomed, it seems, to such intruders. Frozen for a few seconds, I peer across the street (or perhaps it’s a hallway) at a barn gate, encountering a donkey.

Most people have gone to religious services this morning, but a few men nap in hammocks. Women sell colorful handicrafts and molas, bright appliqué waistbands woven in unique geometric patterns on multilayered fabric.

Molas are a major Guna export. Most adult Guna women sew them. The tradition stems from the art that the Guna people once painted directly on their skin — it wasn’t until European colonization that tribe members began wearing much clothing.

Many of the Guna increasingly work at fish stalls, in sweatshops, or as migrant labor in the environs around Panama City or in nearby Colombia. Given their proximity, the outlying islands of Guna Yala are occasionally used by Colombian drug traffickers plying the seas. There have been cases where the Guna have found windfalls washed up from the drug-trade fallout.

Undoubtedly, though, the Guna people in the Cartí region depend heavily on tourism. Prior to the 2020 pandemic, approximately 100,000 tourists visited Guna Yala annually. According to a long-term anthropological study, many of the Guna viewed tourism as a threat in the 1990s but have come to see it as inevitable. Opinions differ between regions, since some areas of the comarca stand to gain more from tourism than others. They also stand to lose more when tourism slows or stops altogether.

Tourism is governed by statutes issued by the tribal leaders that limit the number of guests per island and control the cultural, environmental, and economic changes that the tourism industry brings. All guides must be Guna, for example, and there can be no more than 200 sailing vessels in the area at any time. This ability of the indigenous community to regulate visits to the islands ensures a mitigated scale of tourism and fewer outside interlopers spoiling the Guna’s environmental or cultural sovereignty.

The Guna developed a large-scale eco-tourism business in the name of sustainability. But it’s one thing to regulate tourism, and quite another to relocate an entire people.

~~

Already, there are days on Isle Nonumula where the sea reaches the center at high tide, connecting with water encroaching from the other side.

The grimy, congested “metropolis” of Gardi Sugdub contrasts with the deserted isles further offshore. Yet, our guide, Degimalo, laments that in order to give tours he must live with his family far from the tribe’s hub on one of the outlying cays. The Guna prefer their packed island communities over the remote, pristine islets many would consider a white-sand paradise.

Once we leave Gardi Sugdub, the rest of our visit consists of capering around various serene cays that dot the cerulean seascape.

On one island, I stray to the far side of the beach, where a young boy hacks at a huge pile of coconuts with his machete. I offer him a dollar, and he cuts open a fresh one for me to drink. Until the early 1990s, coconuts acted as the local currency; today they are still used occasionally as an informal unit of exchange.

On another island, the Guna guides unload us from the dinghy and fix lunch. The other tourists pop open beer cans or attempt a game of volleyball. I walk down the shore, examining the beach for shells. I’m fascinated by the abundance of brittle sea urchin husks, sand dollars, and starfish. My beachcombing also turns up plentiful hunks of dead coral: calcified fragments of colonies. The bleached-out, worm-holed rubble is a wrack line of tiny skeletons.

The area had once been a teeming lobster habitat, and the Guna’s seafood haul had made up 70% of Panama’s marine exports. In recent years, though, the lobsters are harder to come by. They hardly make a contribution to the Guna economy.

The coral reef has lately suffered degradation due to runoff sewage, pollution, and algal growth, as well as harvesting for the curio trade, overfishing, tourism, and dredging for infill. Of course, as tourists, we’re shuttled to the remaining vibrant corals, not the brittle ones evidenced by the washed-up chunks. And while the waters immediately surrounding the remote isles in the comarca look translucent as crystal, the darkly iridescent sputum of oil and contaminants dribbling in the Canal Zone lurks a mere 100 miles around the corner.

~~

The reef acts as a breakwater, so as the coral dies off, already-rising sea-levels loom higher. Dredging the living reefs to patch-up the islands is a band-aid solution which further degrades the coral and ultimately causes higher tides.

With more frequent and heavier, monsoon-like rains, on the one hand, and with rising sea-levels, on the other, the islands are often inundated from above and below. Storm-tossed waves already overtop the rudimentary barriers. Many islands remain a couple inches or less above the high-tide mark. Ocean levels have risen nearly a foot in the past half century. Already, there are days on Isle Nonumula where the sea reaches the center at high tide, connecting with water encroaching from the other side.

An evacuation plan for the archipelago was developed in 2010 but, while a few families have shifted islands, nobody has yet moved to the comarca’s mainland. The jungle of the mainland where the proposed resettlement would take place is rife with yellow fever and malaria. Intricate matriarchal land rights problematize any moves or claims to unoccupied space. Moreover, the Guna’s autonomous status complicates the Panamanian government’s role in relocation efforts.

By the end of 2019, the Panamanian government had diverted funds that were once allocated for the resettlement project’s houses, school, and health clinic, to disaster relief in other areas of the country instead. As of this writing in early 2020, not a single building has been fully constructed.

The bulldozed site in the jungle remains vacant and the proposed construction has been halted. The project is hamstrung under the burden to uproot an entire way of life.

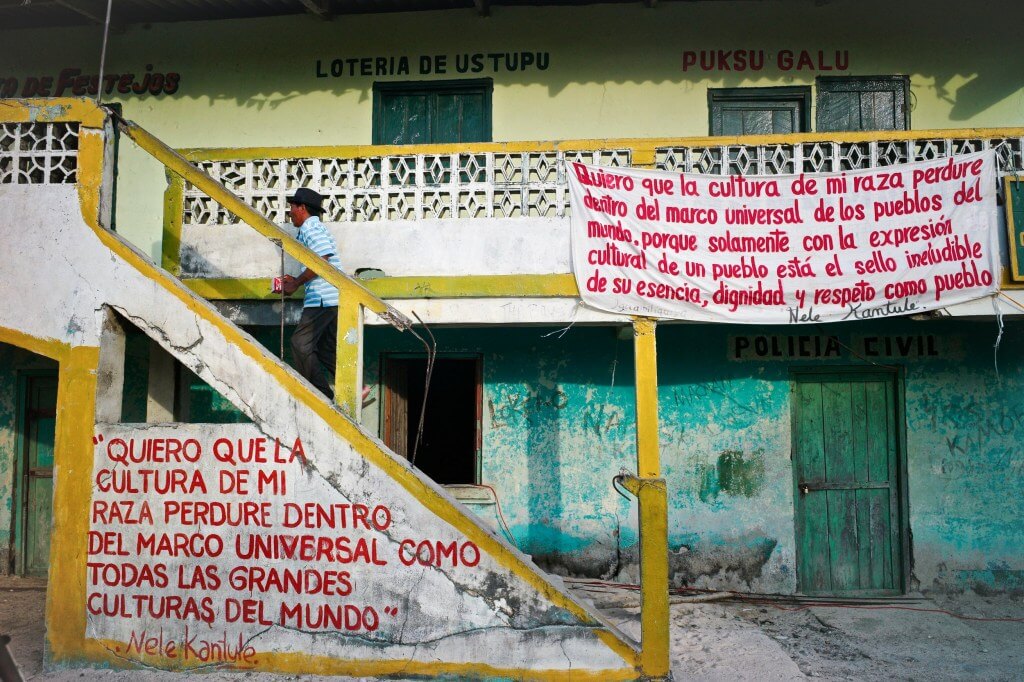

Banners show the words of Guna leader Nele Kantule: “I want the culture of my race to endure within the universal framework, like all the great cultures of the world.” Photo: Kike Calvo / Alamy

~~

After my group of tourists is served a simple dinner of fish and rice, nightfall leaves us with few entertainment options. Degimalo retreats to his family hut. My partner and I sit along the shoreline, casting moonlit shadows which cause nervous ghost crabs to skitter sideways and disappear into marbled sands. Later, we read by headlamps, zipped in our tent’s mosquito net.

I ponder to what extent my vacation might be complicit in causing the Guna’s problems. By far, my biggest carbon footprint was the plane to Panama City from my home base in Mexico. Human flight — like the Icarian myth — comes at the cost of an overheating that could ground us all, even as the ground beneath us here in the islands continues to disappear. Air travel is not nearly as regulated as other forms of transportation, and the volume of air traffic — the 2020 pandemic aside — has been rapidly increasing. In 2019, U.S. airlines alone burned more than 18 billion gallons of fuel.

Then again, small tour groups like ours aren’t the leading cause of reef erosion or sea-level rise. Carry in-carry out strategies and conscious stewardship may alleviate some of our impacts. I’m less wasteful during my time on this remote island than I am at home. And while visitors exact a modest ecological toll on the archipelago, we also help keep up the way of life the Guna depend on, supporting families like Degimalo’s. Of the $2.5 million in annual income of the Guna, 80% comes from the tourism industry. Trade and cultural exchange help sustain almost every community, no matter how indigenous or remote.

Nevertheless, there’s an inherent irony to “last chance” cultural or eco-tourism contributing to the vanishment of the very cultures or ecosystems we seek to witness. Families like Degimalo’s earn several times, say, what a coconut harvester could; but a culture that is now so dependent on tourism will need to radically adjust to new ways of life when climate change impacts vanish the island Degimalo and I both stand on.

My partner and I will soon be heading back to Panama City, where, gazing from shore, I will see a long line of container and cruise ships silhouetting the horizon, awaiting entrance to the canal. These testify to the industries that bear considerable responsibility for the Guna’s plight. It’s my own consumption of global commerce that supports these corporate shipping practices. Laptops and tapioca snack-packs, Coca-Cola and Shop Vacs — all this freight stacked up and squeezed through the locks becomes the cluttered stuff it’s so hard to free ourselves from.

We, too, resist changes that uproot our way of life.

~~

I spend my final day in Guna Yala snorkeling. The mirror-world below is like swimming through an aquarium; fleet schools of angelfish and yellowtails swagger in every direction. I swerve past queen triggers and octopus. Puffers and butterfly-fish crowd and dart through coral. Some of the reefs remain, for now, rich in ecological diversity.

Laptops and tapioca snack-packs, Coca-Cola and Shop Vacs — all the cluttered stuff it’s so hard to free ourselves from. We, too, resist changes that uproot our way of life.

Diving near a shipwreck off Perro Chico Isle, I come face to face with a sunfish, the heaviest of bony fish at over two tons. The clumsy giant glides toward me with its tiny, birdlike mouth. Its elongated dorsal and anal fins resemble a small aircraft flipped on its side. We marvel at each other, two oddballs adrift in the open sea.

Though the sea is considered the grandmother of the Guna, they did not always live on islands. The Guna have relocated at least twice already. They migrated from northwest Colombia in the 16th century and again from the San Blas Mountains to the archipelago a little more than a century ago to flee wars, disease, and colonialism.

At last, the boats return me to the shore of the mainland. Degimalo docks and hands us off to the Guna drivers who’ll take us to our hotel. In an instant, everything changes. The canopy of the rain forest is thick and dark — giant foliage envelopes us in gloom as soon as our SUV trundles down the rutted, mud-slick path.

The distance is short, but the difference is vast. I imagine the islanders heading to resettle in the jungle. It would be a journey fraught with perils and would demand as much adaptation as migrating to a big city. And yet, the Guna have proven themselves resilient before.

The howler monkeys scream and tropical birds chirr by as brief prismatic illusions. Through the dense vegetation, the headlights let us see only so far ahead; riding along the sinuous and uneven road, we take the rest on faith. It’s enough to get us through the dark.

Will Cordeiro

Will Cordeiro cannot drive a car; is not on social media; and may or may not be a human.