Support Hidden Compass

We stand for journalism, science, history, and hope. Make a contribution to Hidden Compass and stand with us.

This story has been published in the 2023 Pathfinder Issue of Hidden Compass. While every story has a single byline, the issue is a collaborative effort. Storyteller proceeds from all patronage campaigns in this issue will go collectively to Team Tété on top of their article pay.

Tété-Michel Kpomassie gazed out the porthole of the ship. A few small icebergs floated on the calm water. “A brilliant sun, cold as steel, glittered on them and transformed the area into a fairy-tale world,” he wrote later, recalling his passage of this fjord in southern Greenland.

As land approached, snow-peaked mountains stood silhouetted against the blue noon sky, some ringed in mist. From his cabin he could see that nearly the entire population of Qaqortoq village had gathered. Wearing headscarves and kamis (sealskin boots), standing hand in hand with their many children, they smiled and watched the ship’s approach expectantly — unaware of the unusual passenger who was about to disembark, to spend 15 months in their homeland.

Kpomassie layered his body carefully — a pullover and hooded overcoat, woolen mittens, two pairs of thick socks, and a pair of army surplus boots. His lungs and nostrils, unaccustomed to the Arctic air, brought stabs of pain with each inhalation.

As he stepped off the ship to a silence so intense, “you could have heard a gnat in flight,” he took in his surroundings — the warehouse, the mountain with the yellow, green, red, or blue wooden houses at its base; the green lichens, and yellow flowers. After days at sea, the sight of this tundra and its people was arresting.

Approaching Qaqortoq by sea means plying an expanse of ice blocks, the smallest of which Tété-Michel Kpomassie wrote “looked like swimming swans,” while others “were like crouching camels rocking gently from side to side.” Photo: Lola Akinmade Åkerström.

His mind, however, was on what the reaction would be to his arrival.

Here was a young African man, skin as dark as a wet seal, standing at 5 feet 11 inches — a full head taller than the adults watching him, who stood around 5 feet 3 inches on average. They stared in shock at what must have felt like a benign alien visitation — the first man from Africa known to explore these shores.

The year was 1965, and Kpomassie’s arrival marked the culmination of an eight-year odyssey to reach Greenland. He had run away as a teenager from his village in Togo, West Africa, to fulfill his dream of exploring the Arctic, and he would go on to write An African in Greenland. Rich in immersive storytelling and anthropological context, his account is an improbable tale of an outsider far from home.

But the question at the heart of the book is most compelling to me, and in fact guides my own explorations: Who gets to tell the story of a place?

~~

Our chopper swung west and then northeast, flying over magnificent snowcapped mountains rising from seas dotted with icebergs that were haloed in electric turquoise water.

It was while writing a guidebook for Togo that I first heard about Kpomassie’s book, more than 20 years ago. I was in Lomé, the capital city of Kpomassie’s homeland, on the palm-fringed corniche and its faded balustrades, flipping through an old edition of the guidebook I was updating. In its back index, I saw mention of An African in Greenland. It seemed so incongruous, that someone from tiny Togo had visited an equally unlikely nation, a world away from West Africa’s humid lagoons. I couldn’t believe that this African man had made it to the Arctic a decade before I was even born, and that he had traveled the same way I did — out of love for exploration.

Born in Nigeria and raised in England, I dreamed of seeing the world. I spent hours as a child staring at maps, watching any TV program that involved travel, and devouring Willard Price’s adventure travel books, wishing I could escape my dull English suburb.

As soon as I was old enough, I poured my resources into traveling abroad. I traveled for fun and also became a writer, starting off authoring guidebooks in places like the Ivory Coast, Madagascar, and Guinea.

However, until I came across Tété-Michel Kpomassie, the people who inspired me to travel came from very different backgrounds than me. And whether in the Malaysian countryside or the rainforests of Madagascar, I almost never encountered other African backpackers. It was with Europeans and Americans that I discussed the joys of eating Ivorian attieké and the origins of the Malagasy people. I was always the Nigerian who was marked out as a tourist by West African locals I met, or assumed to be “a local” in the minds of white Brits who were unaware they were encountering a fellow citizen.

Then I met Lola. A fellow Nigerian travel writer who lives in Sweden, the two of us connected over our mutual admiration of Kpomassie. She introduced me to a Swedish videographer, Erik, and the three of us dreamed up a plan to follow in Kpomassie’s icy footsteps, nearly 60 years later. Particularly as female storytellers of color, Lola and I wondered how our own lived lenses might shape our experience.

The author stands silhouetted against a backdrop of land and sea, on deck a ferry to the port where Tété-Michel Kpomassie first disembarked in Greenland nearly 58 years earlier. Photo: Lola Akinmade Åkerström.

~~

In April 2023, a glorious three-day ferry ride brought my companions and me to that same port where Kpomassie had first arrived, near the southern tip of Greenland. Our ferry took us from the city of Sisimiut southeast along the coast through jagged, snowy mountains and past fjords gilded by the setting sun. Greenlandic families sat at tables and played cards, laughing cheerfully. As we moved closer to the warm south, the icebergs had shrunk to small icy discs, thousands of them bobbing on the water like glass water lilies.

‘A brilliant sun, cold as steel, glittered … and transformed the area into a fairy-tale world.’

Upon disembarkment, I took in the same peak that my hero had taken in so many decades before, but now there were even more of those multicolored houses, sprinkled higher up the slopes like pretty flowers. No crowds of locals gathered, however. Passengers stepped off the ship and into vehicles. They and the locals regarded Lola, Erik, and me with casual interest.

From the quiet dock, the three of us dragged our luggage to a nearby hotel, where a modern lobby mezzanine gave panoramic views of the harbor and the hillside.

“When we had sailed up the fjord, the first sign of [Qaqortoq] was a collection of about thirty little houses made of wood and painted yellow, green, blue, or red,” wrote Tété-Michel Kpomassie in An African in Greenland. The tradition of painting houses with bright hues continues, its roots in a colonial-era system of color-coding that revealed the function of the building or vocation of the inhabitant (yellow for medical institutions and doctors, red for schools and teachers). Photo: Lola Akinmade Åkerström.

The kids we passed in the public playground paused and smiled at us, the usual small-town intrigue at new, foreign faces. Our presence didn’t shock anyone; there were no tears or audible intakes of breath in response to our appearances. The children were more interested in our cameras and posed gleefully in front of our lenses. A girl of about 11 lifted her friend onto her shoulders and her friend flashed a peace sign with her fingers.

~~

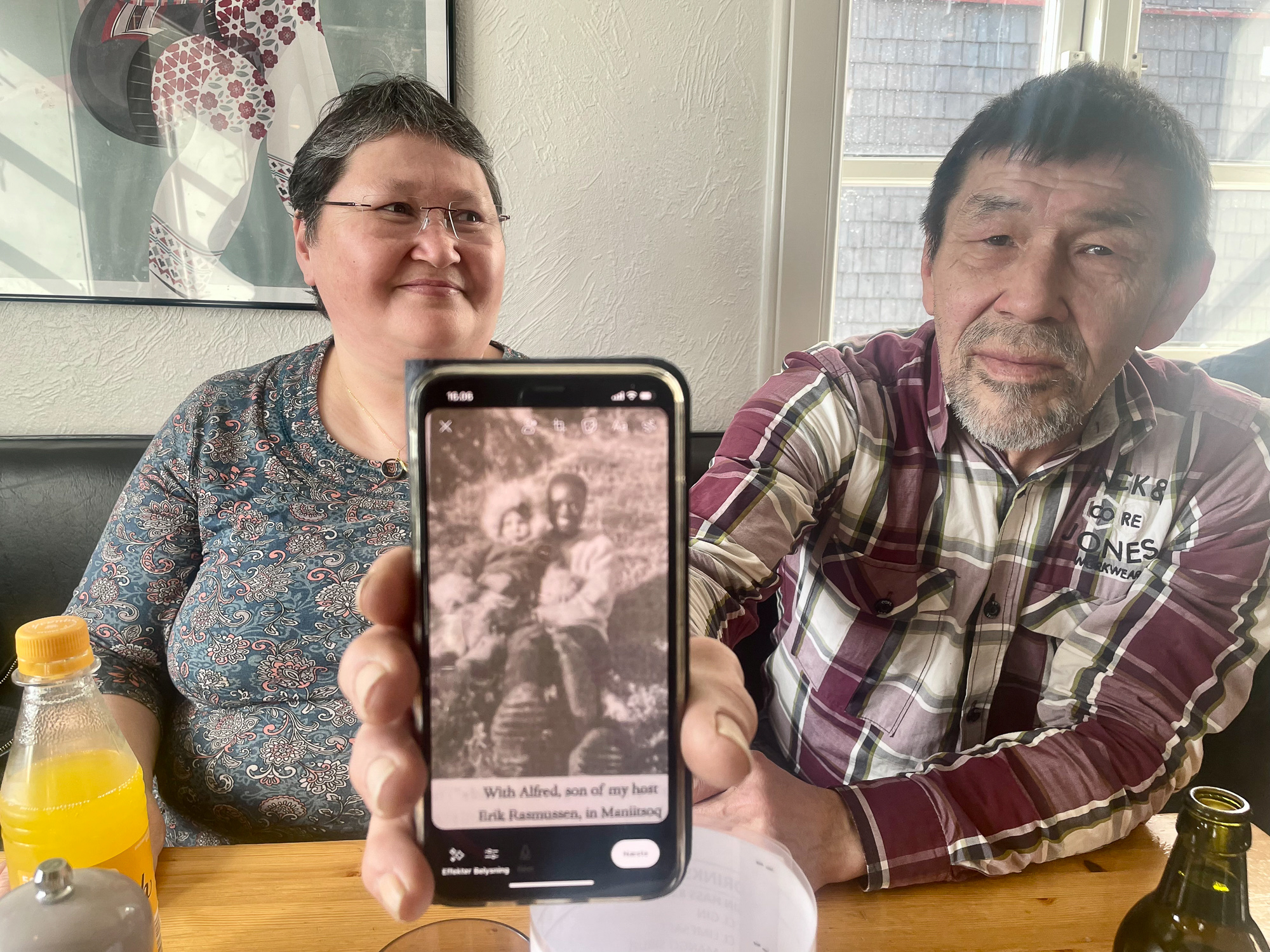

In Kpomassie’s book, a photo shows him — looking every bit the part of an African giant — sitting next to a small child swaddled in animal skin and fur, his small face framed and dwarfed by a fluffy hood.

The child was Alfred Rasmussen, among the gaggle of children who had clung to their mothers’ coats — some screaming and weeping — upon Kpomassie’s arrival, mistaking him for the frightening and evil spirits, known as qivittoq, that live in the mountains.

After we chatted with the hotel receptionist about what had brought us here, she told us how to reach Alfred, now 60 years old. A few phone calls and an impromptu appointment later, we met him at Café Inugssuk with his wife and his daughter, who translated for us. Even now, Alfred was only around 5 foot 2 inches, so Kpomassie must have seemed quite imposing from his three-year-old, grasshopper perspective.

“I screamed and ran to the bedroom and locked the door,” Alfred recalled on first laying eyes on the African man holding his bags on the doorstep of his family home. Alfred’s father Erik, a telegraph operator, had hosted Kpomassie in Sukkertoppen, 94 miles north of the capital, Nuuk, because he was the only English speaker. But Alfred soon got over his fear and became fascinated.

“Every time Tété went to have a bath, we were waiting outside,” he told us as we sat among the wooden tables in the café. “We wanted to see if he would turn white.” Alfred told us how he would take walks with “Uncle Tété” outdoors, with all of the children following him around like ducklings with their mother.

“I had started on a voyage of discovery,” Kpomassie wrote in his book, “only to find that it was I who was being discovered.”

At a cafe in Qaqortoq, an all-grown-up Alfred Rasmussen shows a vintage image of him as a child with a young Tété-Michel Kpomassie; the photo fills a page in An African in Greenland. Photo: Lola Akinmade Åkerström.

~~

While I spent my childhood with my nose in paperback adventures, Kpomassie had spent his youth clambering up coconut trees, gathering fibers to weave into mats and sell in his village in Togo.

One day, after an ill-fated encounter with a snake, he fell 30 feet out of a tree. In a bid to cure his injuries, his family sent him into the nearby forest, in the middle of the night, to meet the head priestess of the snake cult that lived there. During a ceremony, a thick python had wrapped itself around Kpomassie, its “forked, slimy tongue” licking his face, ear, and neck before releasing its hold on the terrified teenager. Through that frightful experience, his fate had been sealed: Once healed, he was to be sent back into the forest, and “pledged to the gods who had saved [his] life.”

In the meantime, Kpomassie visited the local Evangelical Bookshop. By the counter, he was drawn to “a book laid flat on a half-empty shelf,” its cover showing a picture of an Inuit and titled The Eskimos from Greenland to Alaska, by Dr. Robert Gessain. Kpomassie bought the book and read it on the beach in one sitting. “In that land of ice,” he wrote, “at least, there would be no snakes!”

As Kpomassie lay on the hot sand, dreaming of eternal cold where no trees grew, he found that a new longing for adventure had taken root — made more urgent by his fear of returning to the forest. And so, at the age of 16, he ran away from home without a word of goodbye, eventually hopping westward along the West African coast by ship, stopping at several countries to earn and save money, and learning English to add to his French. All the while, Kpomassie rebuffed familial obligations to contribute to village ceremonies back home. His monies were strictly for Greenland.

This determination to save up for Greenland, resisting the pressures of cultural traditions, impressed me hugely — as I, too, have eschewed more traditionally stable career paths in favor of traveling and writing, a poorly remunerated path my mother didn’t understand. “Your friends are becoming doctors and lawyers, and buying properties,” she would say, her voice tinged with concern. “You have two university degrees and cannot get a proper job?”

Until I came across Tété-Michel Kpomassie, the people who inspired me to travel came from very different backgrounds than me.

All told, it took Kpomassie eight years to inch his way around West Africa, set sail for Europe, and eventually reach Greenland. Along the way he educated himself by amassing a suitcase of books, used his evident charm to receive hospitality and financial assistance from strangers, and picked up odd jobs in Ghana, Senegal, Germany, and Denmark.

Like my mother, Kpomassie’s friends questioned how his travels would benefit him financially. His response resonated with me on a deep level: “As if the only reward could be in cash!”

~~

Within hours of stepping foot on Greenland, Kpomassie was presented with a dish full of thick slices of mattak — raw whale skin, blubber, and cartilage. The prospect of eating this local specialty alarmed him so much it crossed his mind to return to the ship and “go straight back to Europe.”

Instead he ate his portion, and politely assured his eager hostess that he had enjoyed the meat. “Whereupon,” he wrote, “she gave me, all to myself, a whole plateful of the stuff, to which she added an enormous quantity of yellowish, blood-tinged seal blubber.”

Over the course of his travels, Kpomassie ate an array of foods exotic to him. I was particularly intrigued by the “thick slab of porpoise” he was once given, “flanked by huge lumps of steaming fat, curled up at the ends.” So, on our second evening in Greenland, when we attended the Arctic Sounds music festival in Ilulissat, I was excited to try some Greenlandic meats for myself.

I selected the “eight-animal ragout”: ptarmigan, hare, walrus, reindeer, musk ox, snow crab, beluga whale, and lamb in a stew. Musk ox — an ungulate found only in the Arctic — tastes sensational: organic and bursting with flavor. Greenlandic people love the taste of polar bear and particularly walrus, which is boiled in water for a long time to avoid infections.

From the music on stage to the food on offer, the Arctic Sounds music festival is a showcase of traditional culture with a modern approach, such as ptarmigan, an Arctic game bird, cooked in a beer and honey sauce. Photo: Lola Akinmade Åkerström.

Later, my stomach full and my spirit lifted by the festival’s music and celebration of Inuit identity, we walked back to our hotel. Streaking the dark skies overhead, green aurora billowed like ribbons, soundtracked by the howls of husky dogs in the distance.

Three months into his stay in Greenland, Kpomassie was walking alone at night when he gazed up to see shimmering curtains of white — then yellow, then pink, then red. This “bizarre phenomenon” in the sky frightened him, and he stood frozen in place for 10 minutes.

“It was like the radiance of some invisible hearth, from which dazzling light rays shot out, streamed into space, and spread to form a great deep-folded phosphorescent curtain which moved and shimmered,” he wrote. Confused about what was happening, he hurried back to his hosts and “babbled” to them about what he had seen. Nonplussed, they explained to Kpomassie that he had just witnessed the aurora borealis.

“I went out to watch it again for a long, long time,” he wrote. “So much more impressive was it than anything I had ever read about these polar auroras.”

It was “as though the world were being newly created before his very eyes,” as British poet and novelist Alfred Alvarez put it in an introduction to a 2001 edition of An African in Greenland. Sometimes, it takes a newcomer’s vision to bring the profundity of a place into a new light.

The awe-inspiring aurora borealis has long inspired legends and superstitions in Greenland. One ancient Inuit tale explained the source of the lights as spirits playing soccer in the sky with a walrus skull. Photo: Lola Akinmade Åkerström.

~~

When I wrote my first travel book, about my journey around Nigeria, I got a firsthand experience of the thorny politics of travel writing, which can be a minefield of pride and territoriality. Though born there, I have never lived in the country, which, to some, made me an outsider; while to others I was an insider whose frustrations with the country were borne out of a love for it.

And Lola says she is sometimes treated like an alien in Sweden, where she lives and raises her kids. As a Nigerian-born travel writer who has written widely about her adopted homeland, she has faced resentment for being an “outsider” who dares to write with authority about that country and the Arctic in general.

In a TEDx talk Lola once gave, she shared a time she was up for a job to create branded content about Stockholm. “By the end of our conversation, the potential client cleared his throat … before asking me why I write a lot about Stockholm, because he had googled me and realized I am African,” she told the audience. “My natural response was to ask him why not? But I didn’t … Instead I told him … as a travel writer, I am moved by curiosity … both abroad and in my backyard. I have also chosen to call Sweden my new home … specifically Stockholm. And if I have chosen to develop roots somewhere, I better know the quality of the soil I have chosen to grow my family and legacy. Because I need to know that new soil on a deeper level, I have made nuanced observations that others take for granted.”

~~

After a sudden jerk, our dogsled accelerated, catching us off guard. Lola was clutching her visor while flailing on her back. Laughing hysterically, we careened down a hill, bumping hard against the ground.

Dog-sledding has coursed through the heart of Greenlandic culture — and served as a vital mode of transportation and hunting — for at least 4,000 years. Of his first long journey by dogsled, Tété-Michel Kpomassie wrote, “With the white of the mountains all around us echoed by white ground under a livid sky, it was like being transported into a world of mist and haze.” Photo: Lola Akinmade Åkerström.

I was reminded of Kpomassie’s sledding experience, his sled flying down a steep precipice and skidding on a stone. Kpomassie was flung in the air and rolled to the bottom, only to be laughed at by his Greenlandic friend who couldn’t believe any man could fall off a sled.

This was my first time sledding, unlike Lola and Erik, but they were as excited as I was, loving the landscape, the speed, and sense of freedom. We soon reached a plain and glided through it.

At home in London, there’s a certain agitation that comes with people jostling for space and ideological supremacy. Here, amid the isolation of the northern latitudes, I could feel myself submitting to my surroundings.

As we zoomed over a frozen lake, Lola exclaimed, “Look at that!” I turned back and saw a beautiful, snow-white valley that contrasted with the bright blue sky. Rarely have I felt so exhilarated and peaceful all at once. The Arctic, I could see now, took hold of people, no matter their background.

~~

One afternoon, while Kpomassie walked down the street in Qaqortoq, a group of elders waved him over to the “Old Folks’ Home” — a place that was unfathomable in his homeland.

In Togo, “as long as the grandfather is still alive,” younger family members wield scant power in the family councils. He could not imagine “our Togolese patriarchs ever agreeing to end their reign in old people’s homes.”

After making the rounds of the place, meeting the residents and admiring their keepsakes — statuettes carved from walrus tusks, and traditional sealskin costumes sewn by hand — he lingered for conversation.

One of the residents began recounting an old hunting story. Though he spoke too quickly for translation, and Kpomassie “lost track of the narrative,” the man acted out each movement with such vigor: from paddling his kayak, “his face shining with sweat,” to the launch of the harpoon and, even, the “death throes of the seal.” Kpomassie found himself holding his breath all along the way. The former hunter acted out, to “much appreciative laughter” in the room, how he spent several minutes blowing air into the dead seal’s wound in order to float his haul back alongside his boat.

“Never before,” Kpomassie wrote, had he “seen a mime which could equal, and even outdo, the power of words.” When he left the home that day, “those fine old men and women” begged him to return often.

~~

The icebergs had shrunk to small icy discs, thousands of them bobbing on the water like glass water lilies.

In Qaqortoq, we walked down to the harbor where a small group of old people sat by the jetty, the frozen carcasses of lumpfish resting on the table. These folks were too young to have remembered Kpomassie.

Jens, a fisherman with a wide smile, invited us on his boat for a brief ride. We zig-zagged through a seascape of icebergs and sea ice, melted and shrunken by climate change, that now made fishing difficult.

Jens, a fisherman in Qaqortoq, navigates a changing seascape. Photo: Lola Akinmade Åkerström.

At one point, Erik and I couldn’t resist hopping off the boat for an impromptu dance party on a chunk of floating ice, Lola laughing as she filmed it on video.

The Greenland Kpomassie visited was quite different from the landscape we encountered. The climate is but one change at play.

While Kpomassie said he was observed as much as he was observing, Lola and I weren’t viewed like aliens. The world is too connected now. Today, Thai takeaway restaurants serve fusion dishes like reindeer panang or seal red curry. Our presence invited a few lingering stares and the occasional photo requests, but we weren’t anything Greenlanders hadn’t seen before.

Although we originate from the same part of the world as Kpomassie, so much more than decades separated our experiences: our perspectives, expectations, and privileges. The same could be said of the Greenland of today and that of the 1960s.

We could follow Kpomassie’s footsteps, but that’s not to say we could ever replicate his journey. Of course, that’s the beauty of travel — the symbiotic relationship between an explorer and the place being explored, the ever-evolving exchange of cultures and insights.

~~

We saw bloodied reindeer legs kept in a box on the balcony of a 61-year-old woman named Augusta, whose purple house in Sisimiut was perched on a granite hill overlooking the ocean. Inside, various ornamental spears and Ulu knives for cutting blubber hung on the wall, some of them heirlooms, alongside tupilaks — carvings of folkloric monsters.

The gaggle of children … clung to their mothers’ coats — some screaming and weeping — upon Kpomassie’s arrival, mistaking him for the frightening and evil spirits, known as qivittoq, that live in the mountains.

Augusta was one of the few people who has a faint-but-defined memory of Kpomassie arriving in her hometown of Upernavik when she was a small child. Now a kindergarten teacher, she remembers being a young child gathering at the fence with other kindergarteners whenever Kpomassie walked past, gazing incredulously at his height and complexion.

She lives with her husband, a retired teacher. Their daughter translated for us while holding her baby girl, who looks like a Cabbage Patch Kid.

“They call people ‘ssuaq’ when they have done something great by their behavior; when they have special qualities,” Augusta said.

Kpomassie’s openness and ability to pick up languages and learn about new cultures was truly special. He conversed with Danish people while working in Copenhagen; he spoke French in various African countries; English while working in Ghana. And within time he could hold conversations in the Greenlandic language, Kalaallisut. Wherever he went, be it in Africa, Europe, or Greenland, people warmed to him and went out of their way to help him. Now that I was in Greenland, I appreciated his personality and spirit even more deeply. He might have viewed his arrival on the island as a triumph in itself and rested on his laurels, reveling in his access. Yet he delved into Greenlandic culture on a spiritual, physical, and cultural level.

That’s why, Augusta explained, he was given a special nickname — Mikkilersuaq.

Michel the Giant.

Not merely a reference to his height, this term of endearment acknowledged his adventurousness, his charm, and his love for humanity. In other words, Greenlanders had appreciated the same things in him that continue to captivate me.

Augusta, a 61-year-old kindergarten teacher in Sisimiut, recalls when Tété-Michel Kpomassie arrived in her hometown of Upernavik more than half a century ago. Photo: Lola Akinmade Åkerström.

~~

Kpomassie, now 82, with short, silvery hair, appeared on my computer screen, wearing a Nordic Marius-style sweater and sitting in front of a bookshelf in his apartment in Nanterre, near Paris. After decades of reading his words, and months of planning our own trip to Greenland, I was thrilled to connect with him face to face, even over Zoom.

Still exuding the vitality and sharpness of a 20-something young man, Kpomassie spoke with an enthusiastic French rasp, his bespectacled face animated, as he talked about his journey in the 1960s — and his excitement for our team’s coming journey.

Kpomassie was seduced by Greenland. Loved it so much he wanted to live there permanently — and, in fact, plans to return soon to spend his final years on the island. “But,” he wrote in the closing pages of his book, “if I were to live out my life in the Arctic, what use would it be to my fellow countrymen, to my native land? … Was it not my duty to return to my brothers in Africa and become the ‘storyteller’ of this glacial land … ?”

That’s the beauty of travel … the ever-evolving exchange of cultures and insights.

While an utter outsider, Kpomassie earned the right to write about Greenland, in my opinion, because he did so out of love and inquisitiveness, as well as a desire to expand the horizons of young Africans — “after the degradation of colonization and the struggle for independence,” as he wrote.

Kpomassie subverted the travel writing genre, writing not from a place of privilege — as so many Westerners had done before and after — but simply from an unceasing curiosity. He’s remarkable not because he was such a curiosity, but because of his profound connection with this place.

It’s clear the feeling was mutual. During our call, he shared one particular memory with pride: “The first time in my life that a girl told me, I love you, was in Inuit. That is something I will never forget.”

~~

Near the end of our journey, we departed by helicopter to the remote town of Narsarsuaq. The winds were relatively low and the skies a clear blue. Our chopper swung west and then northeast, flying over magnificent snowcapped mountains rising from seas dotted with icebergs that were haloed in electric turquoise water. We landed at the Narsarsuaq airport, where the weather is often so dicey that it is one of the world’s most dangerous landing spots. I saw almost no human settlements during the journey — this was wilderness at its most pristine.

Immersing myself in this sort of vastness had a cleansing effect on me, and I was surprised to find myself feeling somewhat despondent about my departure. Rarely do I regret returning to London, no matter how much I enjoy my travels. Greenland was the first place that made me feel otherwise.

Kpomassie’s call had echoed through the generations, and now I craved the all-encompassing immensity of the Arctic, too. It’s my privilege to follow his example and share my experience — and my unique vantage — with the world.

A helicopter ride to the remote town of Narsarsuaq — population 123 — affords vast views of the Greenlandic wilderness. Photo: Lola Akinmade Åkerström.

Noo Saro-Wiwa

Noo Saro-Wiwa is the Pathfinder Prize-winning visual storyteller and journalist for “In Tété’s Footsteps: A Cultural Expedition in Greenland.”

Never miss a story

Subscribe for new issue alerts.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive updates from Hidden Compass regarding new issues and other ongoing promotions such as workshop opportunities. Please refer to our Privacy Policy for more information.