Support Hidden Compass

We stand for journalism, science, history, and hope. Make a contribution to Hidden Compass and stand with us.

Her work here is done. It’s late July in 1898, and Anna Klumpke dries her brushes, eyeing the canvas she’s just finished. It’s a portrait of an older woman with cropped, gray hair and a frank, warm gaze: Rosa Bonheur, one of France’s most successful painters. Yes, Anna thinks with satisfaction, I’ve managed to capture that disarming look in Rosa’s eyes. A look that has haunted Anna for months now, ever since she first set foot in the French painter’s drafty, eccentric château, tucked away in the forest of Fontainebleau.

The studio door creaks open and the real Rosa slips in. Shirt rumpled, pants muddied, hair damp from the rain. She’s been out with her horse, Panthère. One of many guests, alongside the pet lions, wild mustangs, goat-antelopes, bulls, and boars that Rosa likes to keep.

“You’ve finished, then?” she says, voice husky from decades of smoking.

Anna nods, steps aside to let Rosa see the painting, and steels herself for critique.

Planting herself beside Anna, Rosa frowns hard at her portrait.

Anna watches her warily. Truth is, Rosa’s put off their sittings, time and again. Too hot, too busy, too tired — she made up so many excuses that Anna found herself wondering if Rosa had changed her mind. Could she have seen Anna’s brushwork and decided she wasn’t good enough? What should have taken two weeks had stretched into nearly two months. But now, it is done.

The most talented person Anna’s ever met turns from the painting, face as serious as the grave. She slides her hands onto Anna’s shoulders. Oh, God, Anna thinks. She hates it. She’s going to be nice about it, but she hates it.

“Won’t you stay?” Rosa whispers.

Anna blinks in surprise.

“You’ve brought my heart back to life. Won’t you please stay and live here with me?”

Her honesty stuns Anna. Rosa’s hands on her shoulders are like the forest sparrows — light and brave and prone to disappear at any moment if Anna makes too sudden a move. She swallows.

“You’re hesitating,” Rosa says, letting her go. “I suppose you have a man waiting for you on the other side of the Atlantic.”

“No.” What a preposterous idea. “No, it’s not that.”

“Then what?”

There’s only one way forward: Anna reaches for Rosa’s hand. It is soft and tiny and warm. “I’m just not sure I can handle all this joy,” she whispers, and brings Rosa’s hand to her lips. The portrait watches on, forgotten, as they kiss.

At least, this is the version I imagined.

Anna Klumpke paints a portrait of Rosa Bonheur in 1898 in the studio Rosa built for her. Photo: Unknown photographer.

~~

One hundred and twenty-two years later, the forest of Fontainebleau is still redolent with moss, wild boar, and boulders. The Château de By has stood the test of time. Renovations are in full swing, and the property is now a private museum, high-end B&B, and tea room. Strolling through the gardens before a guided tour, I stop in front of the extension — a studio built just before Rosa’s death. A pair of initials engraved above the door: AK for Anna Klumpke, who decided, despite the 34-year age gap, to accept Rosa’s invitation that fateful summer of 1898. And RB for Rosa Bonheur, who, in her enthusiasm, promptly built Anna her own wing.

Carole, my wife, stands beside me, snapping pictures. It’s the first time we’ve been able to make it out of Paris since the COVID-19 pandemic began, and compared with our grim view of concrete towers, everything here seems to shimmer with life: the leaves, the grass, Carole’s unruly halo of curls, her eyes as she takes it all in.

Not particularly enthusiastic about history herself, Carole is used to humoring me on my rabbit holes of research. She’s the kind of person who makes friends with strangers with remarkable ease. Meanwhile, I often find the dead easier to understand than the living. I take walks in the cemetery for fun, keep books by long-gone authors on my bedside table. And again and again, I’ve drawn strength from stories of women of the past who followed their desires, against all odds.

Coming across Rosa in an encyclopedia of lesbian history, I’d read that she was the first woman in France to live openly with another woman. This, more than her illustrious career or masterful brushwork, is what has brought us here.

The tour is about to begin. Carole is already drifting toward the meeting point, nodding at the other visitors. As I turn from the double initials, I can imagine Rosa rounding the corner, cigarette hanging from her lips; Anna, tall and watchful by her side. I feel a swell of gratitude.

Catching up with Carole, I slide my hand into hers and give it a little squeeze. We are here to pay tribute to these women who broke ground for us, these queer women who dared to love.

~~

“They were just very, very good friends,” says our guide.

We are in Rosa’s study, and we have come to the end of our tour.

Our guide is talking about Nathalie Micas, Rosa’s first partner. From an oval frame hanging above us, Nathalie looks on: a pale and sickly face, an impressive bun and high forehead, a dreamy expression. Over the last hour, we’ve been given a vivid picture of daily life at the château: Rosa’s illustrious guests, her astonishing rise to fame; her exotic menagerie; and Nathalie’s inventions and experiments.

Lou, our guide, has referred to Nathalie all throughout as a friend. This is an unsurprising euphemism, one I have encountered many times growing up here in France. But still, it’s 2020, and it disturbs me enough to clarify, once the other visitors drift away: “Rosa and Nathalie were in a romantic partnership, weren’t they?”

Rosa, it seems, does not want to be found.

Lou looks to be in her late 20s, just a few years younger than us. She is dressed in a fashionably soft sweater and elegant slacks. To my surprise, she shakes her head. “That’s a common misconception,” she says. “It was just a rumor, spread to discredit her work.”

The encyclopedia I had consulted was edited by Bonnie Zimmerman, an award-winning women’s studies scholar. Had there been a mistake?

“There’s simply no evidence.” Lou is apologetic, but firm. “Here at the château, we tend to believe they were just very good friends.”

“And with Anna Klumpke?”

“Oh no,” Lou looks a little horrified. “Rosa was nearly 40 years older than her — Anna was like a surrogate daughter to her.”

In Rosa’s study, everything has supposedly been left just as it was the day she died. On a stool, a pair of remarkably small boots. An apron draped over a chair. A palette with dried crusts of paint, and a set of reading glasses, left out on the desk. A painting rests on an easel in a corner, unfinished. My understanding of Rosa flickers, like the leading horse on that canvas — there but also not there.

Today, Rosa’s studio remains in her historic home. At right, a painting sits unfinished, evoking the legacy of the painter herself. Photo: Carole Cassier.

~~

It’s late July in 1898, and Rosa has just finished taking Panthère back to the stable. She knows the portrait is finished — Anna has surely put the final touches on it today. She paces in front of the studio, working up the courage to go in.

Rosa’s fond of the girl, her portraitist and protégé. Anna looks up to her, worships her even. And Rosa has to admit, it’s grown on her. It’s the first time since her friend Nathalie died that she finds herself eager to get out of bed again in the mornings. She doesn’t want Anna to leave, and she runs through what she can offer, were Anna to stay: the pleasure of her company, sure, but also professional connections, guidance, opportunities the young Bostonian may never have back home.

Right, here we go. She straightens her shoulders, opens the door.

Anna turns from her canvas with a bright smile.

Rosa strides up to her, puts two motherly hands on her shoulders.

“Won’t you stay?”

This is the version they would have me believe.

~~

On the train back to the city, zipping past the venerable trees of Fontainebleau, I can’t help feeling like I’ve been robbed of something. What was it that I had hoped to find here in the heart of the forest, and what was it that had been taken away?

~~

When we meet her, the feminist activist and local politician Alice Coffin looks a little hounded. She has moved recently. The walls of her Paris apartment are still mostly bare, and she asks us not to disclose her address. Her views have caused such furor online that she has had to shutter several social media accounts, accept police protection, and contend with disruptions at public events.

She’s wearing a T-shirt with a fake Nike sign that reads “Monike Wittig,” a callback to the French feminist theorist and lesbian whose footsteps Coffin is walking in. In her recent book Le Génie Lesbien, Coffin notes that despite major advances in civil and reproductive rights in recent years, France is still one of the countries in Europe with the lowest number of openly LGBTQ+ public figures. It comes last after 17 other countries on an EU-wide ranking, and only 0.3% of its parliament members are out, according to an activist tally in 2015. Coffin calls this phenomenon the French closet.

‘I love you deeply … but what will our family, our friends think?’

“To publicly state that you are gay or lesbian is not like pulling down your pants in the middle of public speaking,” she says, “but in France, the gesture is considered just as inappropriate.”

Coffin speaks with a Parisian lilt and the energy of someone who’s used to fighting for air time. “There’s this idea of universalism, this idea that we all have to be the same … and so to place a public figure, like an artist, into a specific category actually undermines their legitimacy. Assuming it’s well-meaning, [the media] don’t want to limit a writer’s reach by putting her into the category of a lesbian, as though being a lesbian might somehow prevent us from having a universal message. Of course, that’s not the case. But this is why in French discourse, any specific belonging or identity will so often be masked.”

When I mention our visit to the museum, Coffin is unsurprised.

“This happens all the time. I have to laugh sometimes, it’s so absurd. The number of times I’ve been to exhibits and thought: Come on, stop pretending like they were the best of friends! There’s an attempt to hide or erase what’s staring you in the face, to the point of becoming ridiculous and absurd — how far is society willing to go to stick to its guns and ignore the obvious?”

~~

On my way back from our visit to Fontainebleau, I double-checked Rosa Bonheur’s Wikipedia page. There it was, stated as fact within the first two paragraphs in English: “Bonheur was openly lesbian. She lived with her partner Nathalie Micas for over 40 years until Micas’s death, after which she began a relationship with American painter Anna Elizabeth Klumpke.”

When I toggled to the French version, something interesting happened. Those two sentences disappeared. No mention was made of her private life at all until the very end of the entry, where the factoid reappeared — except it was no longer presented as fact, but rather theory, and came packaged in a convoluted sentence with footnotes that suggested an editing war had taken place. Here is my rough translation:

“Though the lesbianism of Rosa Bonheur, claimed by some and refuted by others, has never been proven, she did write in her will that she ‘had no children nor affection for the opposite sex …’ and she lived in actual companionship with two women.”

There’s an attempt to hide or erase what’s staring you in the face, to the point of becoming ridiculous and absurd.

What happened to the breezy brevity of “Bonheur was openly lesbian” in English? Why this buried, overwrought, and unclear sentence instead? This discrepancy between versions squared with Coffin’s take on the French closet.

What I thought would be a romantic visit to the château had now become something else.

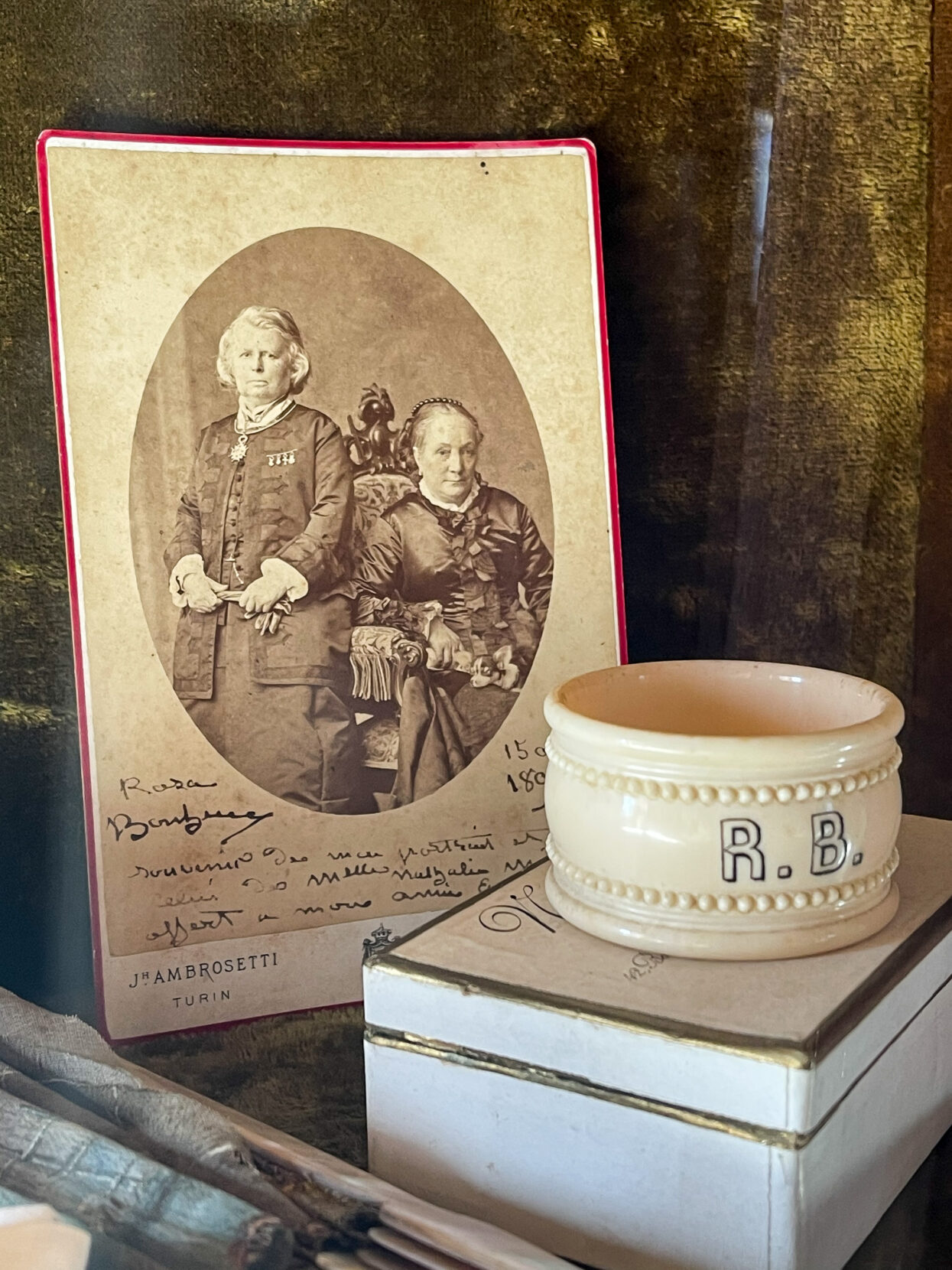

A photo of Rosa with Nathalie Micas rests on a table at the Musée Rosa Bonheur. Photo: Carole Cassier.

~~

Ten years after meeting Rosa, Anna Klumpke published Rosa Bonheur: the Artist’s (Auto)biography. In it, she included her own diary entries from when she first arrived at the Château de By, as well as lengthy interviews with Rosa.

In the months that followed our visit to the château, Carole and I carried our copy on train rides and hikes, taking turns reading passages out loud whenever we stumbled across what could be conceived as evidence.

“Had I been a man,” Rosa confesses to Anna, “I would have married [Nathalie].”

Rosa states, again and again, that no joy is complete without Nathalie by her side. Nathalie’s father blesses their union on his deathbed, and at the château, Nathalie takes on the role of a traditional wife, running the household and tending to their menagerie. When Nathalie dies, Rosa mourns her for nearly a decade. When Rosa falls ill herself, she wants to breathe her last in Nathalie’s bed and requests to be buried in the same grave. She asks Anna to join her there as well, promising that Nathalie, despite her jealous nature, “would understand.”

At the very end of the book, included as an annex, is Rosa’s will. In it, she leaves everything to Anna. “Having never had any affection for the opposite sex,” she writes, “aside from a frank friendship for those who held my esteem, I believe I can live a life for myself.”

~~

I keep returning to the moment when Rosa asked Anna to move in with her.

Here is the original scene, written by Anna Klumpke in French, and translated into English by me:

Quite late this afternoon, Rosa Bonheur came to the studio where I was working on the big canvas. She examined the portrait with a distracted eye and praised it briefly. Then turning to me, she put her hands on my shoulders. While I looked on with some surprise, she said in a pleading, tender voice: “Anna, won’t you stay with me and share my life? I have grown attached to you. Life will seem very sad indeed when you are no longer here. I will be so alone … you make my heart feel young again,” she said. “You give me energy again to work. I’ve felt discouraged by life ever since my dear Nathalie died, because I’ve been alone these nine years. And now, you’ve begun to replace the person I can never forget. Wouldn’t you like to stay here with your old friend, who will adopt you like her child, and who will help you make beautiful paintings?”

My heart was pounding, my throat felt so choked up with emotion I could not respond.

“You hesitate, Anna. You say nothing. Oh! Perhaps you’ve left a lover on the other side of the Atlantic?”

“No, no, it’s not that.”

“Then what is holding you back? You can work here better than in Boston. I will guide you in your brushwork, we will share our inspiration, and you will make me so happy.”

There were tears in my eyes. I finally answered:

“It’s too much joy for me. All this is so unexpected, so unusual. Give me time to think. I love you deeply, I want to do everything I can to make you happy. But what will our family, our friends think?”

[…] I would have liked to throw myself into her arms, but I didn’t dare.

The completed portrait of Rosa, painted by Anna in 1898. Painting: Anna Klumpke.

~~

Carole and I are both trained reporters — although we met by chance in a bar nine years ago, we could just as easily have crossed paths at a press conference. While I was learning to package news items for the French wire service, Carole was shooting footage of picturesque towns for a popular TV show. Even as we moved away from hard news and reporting, I held onto the idea that we’d make a great team: We’d never worked together professionally, but I dreamed about what it would be like to pool our creative energy into a single project.

By the end of Klumpke’s biography, it has begun to dawn on us both that we’ve stumbled straight into our project. We return to the museum a second time in early 2021, armed with an idea for a documentary and a series of questions.

The owner, Katherine Brault, greets us in the tea room, phone in hand. It turns out our earlier guide was her daughter, and there’s a family resemblance in the way Katherine’s eyes shine when talking about the woman whose memory she feels called to preserve.

When it comes to Rosa’s sexuality, however, Brault is adamant. “The LGBT community got it wrong when they picked Rosa,” she tells us. “I can say with quasi-certainty that she was not a homosexual.”

The winter sun creeps across the rug as I trot out my evidence and Brault parries each item, blow by blow: Yes, Rosa said that thing about marrying Nathalie, but she was just trying to protect her friend’s reputation. Yes, Nathalie’s father gave them his blessing, but he was just telling two spinsters to stick together. Sure, Rosa may not have found men attractive, but did that necessarily make her gay?

The camera has been rolling for more than an hour when Brault’s professional demeanor slips. “I don’t know what went on between them. And honestly, I couldn’t care less,” she says. “But I can tell you one thing: If I don’t know, then no one else does, either.”

It’s clear that she finds discussing Rosa’s private life in such detail distasteful. Do the dead not deserve as much privacy as the living? Why won’t we, two complete strangers, stop shoving our noses into Rosa Bonheur’s most intimate affairs?

~~

What was it that I had hoped to find here in the heart of the forest, and what was it that had been taken away?

It’s a cold day in January. I stop near the entrance to the Père Lachaise cemetery, at a small flower shop that sells mostly sad-looking chrysanthemums. I know Rosa’s fondness for roses: Anna’s mother, when visiting them for the first time, admired a rose bush near the entrance. Rosa, in her eagerness to please, had her gardener promptly uproot the bush and gave it to Anna’s mother.

Père Lachaise is on a hill, sectioned into several dozen plots, each of which contains hundreds of the dead. I have one such plot number, and an old photograph of the grave to help me. I comb through the rows, weaving up and down. Rosa’s final resting place is hard to find — not unlike her home in the forest of Fontainebleau, where she would be visible only to those she chose to let in.

I’m here because Carole and I have submitted a grant proposal for our documentary. The project has morphed from telling Rosa’s story to telling the way it is being told. We’re not claiming we can solve the mystery of what went on behind closed doors in the château. All we can do is chart its contours, and why it’s relevant today. I am here to ask Rosa for permission, to pay my respects and hope for a blessing. But Rosa, it seems, does not want to be found.

~~

Combing through the graves, I think of the story of Anne Lister. Born in 1791, Lister was a British aristocrat, billed as the first “modern lesbian.” We know this because she kept a meticulous, coded record of her sex life. Her diaries remained in the family mansion long after her death, until her descendent — a closeted gay man himself — decided to take a closer look at the sections in code. Working with his partner one evening in the 1890s, John Lister managed to crack the cipher. So astounded were they by what they found that they nearly threw the notebooks into the fire. In the end, the diaries were hidden behind oak paneling for another 40 years. It was only after John died that his partner donated them to the local archives.

Anne Lister’s private affairs — whom she slept with, what it felt like — are nobody’s business but her own. She encoded her diaries precisely because she didn’t want anyone reading them. But had her privacy been respected, I wouldn’t know about her today. And that would be a shame, given how few stories of queerness have carried over from her time.

We are here to pay tribute to these women who broke ground for us, these queer women who dared to love.

Despite the clear choices of Rosa Bonheur’s will, she is unlikely to have left explicit, written evidence of her romantic life. And I understand why: Until now, I made that same choice.

For years, I’ve been careful about what information can be found about me online. I’ve avoided being too “obviously gay” in case it affects how a potential employer perceives me. Although I am married to Carole in real life, I have hesitated to link my name to hers online. This article, for Hidden Compass, is the first time I’m writing explicitly about her.

In fact, I tried writing a version of this story without mentioning her at all. In my second draft, she was only a letter. It took a third try for me to understand that there’s no way to tell the story of Rosa Bonheur’s love without including my own.

~~

I’m about to give up on finding the grave, when finally I see it: the oxidized iron ribbon and branch on the tomb, and above that, her name. The tomb is high; it reaches my shoulders. All three women — Nathalie, Rosa, and Anna — are buried here. I place the flower on the rim and look at the words etched into the rock. “Friendship is a divine affection,” the ribbon reads. That word again.

When I turn to go, I catch sight of something on the tree directly opposite the tomb. A hand-drawn heart, and inside it, scrawled in black marker, is a seeming wink from the netherworld. Upon reading it, I laugh.

It reads: “Lesbianism is a divine friendship.”

Anna gazes at Rosa as the two pose for a picture at the Chateau de By, circa 1898. Photo: Unknown photographer.

Anna Polonyi

Anna Polonyi is a writer and former reporter with a love for uncovering stories of unexpected courage in history.

Never miss a story

Subscribe for new issue alerts.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive updates from Hidden Compass regarding new issues and other ongoing promotions such as workshop opportunities. Please refer to our Privacy Policy for more information.