READER SELECTION

This Intrepid Interlude was hand-picked by the badass members of The Alliance.

Want to vote on upcoming pitches?

This is the third installment in a four-part “Intrepid Interlude” series by Hidden Compass’s 2025 storyteller in residence, Tulsi Rauniyar. Earlier this year, Hidden Compass Allies voted to assign a story series on human-tiger conflict in Nepal. For Part One, Tulsi explored the theme from the perspective of local residents. In Part Two, she brought in the perspective of park authorities. In Part Three, she grounds the story in a new voice.

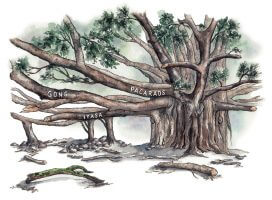

The people say that long ago, when God opened his treasury to all castes in Nepal, they walked the same dusty road toward divine wealth. But when the path curved through the kathban bamboo, my forest rich in wood, the Tharus slowed. While others marched past my trees like soldiers toward promised gold, the Tharus lingered. They touched my bark, tested my wood grain, and breathed my forest air. They forgot God’s appointment entirely. When the others returned, pockets heavy with coins, the Tharus emerged empty-handed from my cathedral of leaves, carrying only the scent of sal and sissoo in their hair. This is the story the people tell — not a myth but a prophecy.

~~

We step off the dusty track and into Nepal’s Bardia National Park, where the air changes: It is cooler, damp with the breath of leaves. Bajari’s bare feet grip the forest’s root-laced path, and I can hear her humming under her breath — fragments of melody that seem to match the rhythm of her steps. She stops beside a great stump, its rings grayed with age.

“My father’s cattle,” she says, “rested in summer shade here.” Her hand lands on the wood like she is patting an old friend. “Tigers would drink at that spring there every evening. Everyone knew this. So we made sure to finish our work and head home before dusk.”

She gestures toward a barely visible trail that winds deeper into the trees. “That path leads to the old fishing pools on the Babai. In those days, anyone could cast nets there.”

~~

A river crossing in the Terai. Photo: Dave Hohl, 1967 / Courtesy of the U.S. Peace Corps / Rounds Imaging Archive.

No one owned the river. No one counted how many fish were caught. No one drew lines saying, “this is human land, this is animal land.” Dense sal forests and tall grasslands supported one of the densest tiger populations in South Asia. Dozens of tigers were visible within a single expedition across my territories.

In one of the few intact tiger landscapes on the subcontinent, tigers followed deer paths that doubled as human trails, drinking from pools where children learned to swim, marking territory that overlapped with village boundaries. They padded down to my streams in the evening while families cast nets in the morning. Their pugmarks pressed into my muddy banks beside bare human feet, both seeking what I offered freely. It wasn’t always peaceful. I belonged to everyone and no one.

~~

Bajari reads the forest like one reads faces. She reads it by smell, by sound, by the way birds call or fall silent. The way she describes the landscape, it seems the forest around us isn’t just a habitat or ecosystem, it is a palimpsest, each layer of use and meaning written over the last but never completely erasing what came before. What looks to me like empty clearings and random stumps are inscribed with generations of negotiation between her people and the more-than-human world.

Listening to Bajari, I struggle to understand how her family’s relationship to land worked. There were no deeds, no sales, no individual ownership.

“During my grandfather’s time, land belonged to everyone and no one,” she explains, seeing my confusion. “The badghar, our village council, would decide which family used which areas, but you couldn’t sell it to outsiders. You couldn’t own it like you own a cooking pot.”

Later, reading anthropologists’ research on Tharu communities, I found language for what Bajari had described: virtual isolation from the state and rights of usufruct recognised and enforced by the community itself.

What struck me most was how long this system had persisted. For generations, Tharu villages operated completely outside Nepal’s formal land tenure systems. The land arrangements that governed property elsewhere barely touched these forest communities.

A young Bajari smiles at the camera. Photo: Courtesy of Bajari.

~~

I became famous for my forests teeming with tigers, wild elephants, and one-horned rhinos, but it was something far smaller that shaped my destiny: the mosquitoes that carried malaria through my swamps and rivers. Among them, the tiny Anopheles minimus bore the fever — a deadly affliction that could twist bodies with seizures, steal sight, scramble the mind, and drag its victims toward coma or death.

For centuries, this fever was my invisible guardian, felling outsiders who lingered too long. The Tharu were not untouched — infants often fell ill, and some were lost — but their communities suffered far less often and with far fewer deaths than others. That hard-won resilience kept most hill people at bay, allowing traditional governance to flourish without interference.

~~

“We could live here because the malaria fever couldn’t touch us,” Bajari says, settling onto a fallen log that had become soft with moss and time. “Every year, when the rains came, the sickness would rise from the swamps and rivers like invisible smoke. Outsiders who tried to settle here would shake and burn with fever until they fled back to the hills or died trying to stay.”

She rolls up her sleeve and points to her palm. “My mother used to say our blood learned to fight the fever over so many generations that it became part of us. Like how lotus blooms in stagnant water while other flowers would die, we thrived in places where others couldn’t.”

This biological barrier lasted for centuries. Even during the British administration of the western Terai between 1816 and 1860, malaria kept most outsiders at bay. It didn’t just protect individual Tharu bodies; it protected their land and ecosystem. Without competing claims on forest resources, Tharu communities could maintain their rotational use patterns and customary laws.

But just as malaria shaped Nepal’s past, its almost complete removal in the 1960s and 1970s shaped Bardia’s present.

~~

They arrived in the 1950s, men with metal tanks strapped to their backs, trailing a sharp, chemical haze through my forests and villages. DDT, they called it — a man-made miracle to strike down the mosquitoes that carried malaria. The World Health Organization and the United States promised salvation, and here in Nepal, unlike so many other places, their plan worked. Within a few short years, the fever that had guarded me for generations simply vanished.

But after the fever died, I sensed new footsteps in my once-forbidden lowlands, strangers moving through the tall grass, felling trees in great swaths, reshaping boundaries, and shifting power. Among the Tharu, elders gave DDT a new name: “Deadly Dose for Tharu.” The chemical that spared lives, they said, had stolen their ancestral lands — and with them, an entire world built from my soil.

~~

One of the first tractors in the Terai clears forest to make way for new settlements. Photo: Dave Hohl, 1967 / Courtesy of the U.S. Peace Corps / Rounds Imaging Archive.

“We watched it all happen. I still remember how the land trembled when the first bulldozers arrived,” Bajari continues. “First came the hill people after the fever disappeared. Families carrying everything they owned, looking for flat land to farm. Then, people from across the border in India. By the time I was born, the region was full of faces we’d never seen before.”

The scale of change was staggering. By the 1971 census, a large portion of the Terai’s population were recent hill migrants or their descendants — families who had moved down in the years after malaria eradication opened the lowlands. Districts like Bardia, once insulated by disease, were suddenly transformed.

“Many families lost everything during those years,” Bajari says. “People who had never borrowed money before began taking loans from the hill migrants. Some borrowed to buy ploughs or tools for new farming methods, but many took loans simply to cover basic needs, weddings, illnesses, and food during hard seasons. The loan agreements were written in Nepali, which most Tharus couldn’t read. When they couldn’t repay, they lost their land.”

Sitting here, I begin to understand: For generations, communities like Bajari’s never needed to document land ownership because they had been the only people who could survive here. But suddenly, their territories were contested by newcomers who arrived with papers and connections.

This displacement created the brutal Kamaiya system of bonded labour. “My relatives were also Kamaiyas,” Bajari says quietly. Entire families were tied to landlords through debt, working as servants on land they had once freely roamed. The system was officially abolished in 2000, but during my time in the region, I met families still trapped in remarkably similar arrangements.

A felled tree in the Terai during forest clearing for settlement and road expansion. Photo: Amrit Bahadur Chitrakar, courtesy of Nepal Picture Library.

~~

In 1969, new uniforms appeared among my trees as the state declared me a Royal Hunting Reserve, a playground for Nepal’s elite. I heard the measured footsteps of officials mapping my contours, while my ancient groves became arenas for royal hunts. The tigers and rhinos who had padded my paths alongside the Tharu were now chased and slain, their deaths celebrated from elephant-back in rituals of power.

In the 1970s, it was decided I should become a protected conservation area. Fresh signposts were pressed into my soil, staking claims. As my boundaries stretched toward national park status, I felt the shudder under the trucks that carried away over 1,500 human households from my valleys. Families who had grown roots into my soil for generations were unceremoniously uprooted, deemed incompatible with the conservation of wildlife. Their steps faded, leaving the soft spray of mist and the chill that clung to my forests long after they were gone.

~~

“I was a young girl when that happened,” Bajari says. “We were among those who were moved out. They didn’t ask us anything — just told us we had to go. Many families, like ours, didn’t really understand what it meant. The government people said, ‘Don’t worry, we’ll find you land somewhere else, we’ll help you resettle.’ But most of the time, they gave us very little, or they made us wait for years, or they just forgot about us completely.”

Bajari’s family was relocated and allowed to settle on government property, but even after decades of living there, they haven’t received legal rights to the land.

“When the tourists started coming to see the animals, my son Manmohan thought maybe he could find some work here,” Bajari says, her voice softening. “So he became a nature guide.

“There were so few ways to make money after we lost access to the forest. The tourists came to see the animals we once lived with, so he learned to show them tigers and rhinos. He was good at it.”

Bajari takes a slight pause. “Ten years he did that work. Ten years without anything going wrong.” Her voice catches. “And then …”

Manmohan set out with his guest along the familiar trails of the Dalla community forest, a route he had walked countless times in his decade as a guide. When they rounded a bend in the path, they found themselves face-to-face with a mother rhino and her young calf. Mother rhinos are fiercely protective, and with her offspring nearby, the animal perceived the humans as a threat. In the critical seconds as the rhino lowered her head and charged, Manmohan acted on instinct. He pushed his guest toward safety, but there wasn’t enough time for both of them to escape. The rhino struck Manmohan with the full force of her protective fury.

~~

Humans are counting the deaths, statistics of ‘human-wildlife conflict’ for their databases. Tigers were responsible for three-quarters of these incidents. I recall the footprints of Padmakala Thapa, just a few kilometres from this spot, killed by a tiger while she tended her livestock. She died in the same place as Bajari’s son: in the dwindling space between coexistence and survival.

~~

“I heard you were murmuring songs while walking. What were you singing?” I ask.

“I only know Tharu songs,” she says. “I know ceremonial songs … the ones you sing when you’re wishing or praying.”

“What are you wishing or praying for?”

“I wish my son were still alive. I wish my son had not stepped into the jungle that day.”

Less than a year after her son’s death, Bajari still speaks of wanting to rewind the clock, to undo the morning she watched Manmohan walk into the forest for the last time.

As we walk back toward the village in the fading afternoon light, Bajari’s story settles over the landscape. The forest around us hums with the sounds of successful conservation — the distant trumpet of elephants, the alarm calls of spotted deer, the rustle of rhinos moving through tall grass. By most measures, Bardia National Park is a triumph. Tiger populations have recovered from near extinction. Rhino numbers have grown steadily. International tourists bring valuable revenue. But these successes exist alongside a harder truth.

“I hear about other people being attacked, being killed. People say the animals are the problem now,” Bajari says, looking toward the forest where her son died. “But the animals are just trying to live in a world that keeps shrinking around them. We all are.”

Bajari holds a portrait of her late son. Photo: Tulsi Rauniyar.

Read the final installment of Tulsi Rauniyar’s four-part Intrepid Interlude series here.

Tulsi Rauniyar

Tulsi Rauniyar is the 2025 Hidden Compass Storyteller in Residence and a 2026 Pathfinder Prize finalist.