Ad Free. Reader Funded.

Hidden Compass is on Team Human. This article was crafted without generative AI. Support the journalist and editors of this piece with a direct contribution!

% of $ Goal

Total number of contributions so far:

0

Total amount raised for journalists

$0

"One thing I really appreciated about working with Hidden Compass is that it's a space where there is time for nuance and complexity. By donating, that's what you're supporting. You're able to help us as writers, but also as an outlet, continue to tell these kinds of stories."

- Anna Polonyi, Hidden Compass Journalist

"The reason why I contributed was because the article that I read really resonated with what I was feeling. I felt like the author was in my head... It just moved me and I felt like I needed to do something."

- Hidden Compass Reader

On a sunny summer Friday in the town of Astoria on the northwest tip of Oregon, I wandered down a shop-lined street between Pioneer Cemetery and the vast Columbia River. I passed the Flavel House Museum (rumored to be haunted) and the Uppertown Firefighters Museum (also haunted), stopping at the corner of Commercial and 12th.

A 99-year-old building rose above the coffeehouses and antique stores, frosted in a white stone façade. Its arches and columns and curlicues — sculpted in Italian Renaissance style — towered over an elegant domed awning wrought from green metal and protecting a box office walled, diamond-like, in glass.

I paused before the building as people strode by on their way to shops and lunch spots, seemingly unaware of the landmark’s grand history. As for myself, I could almost see the 1920s loggers and fishermen with their families, dressed in their finest clothes, crowding under the awning to escape Astoria’s omnipresent rain. I imagined them pushing toward the building’s ornate wooden doors, laughing and shouting in anticipation of the spectacles within.

“[He was] the funnest man I ever saw — and the saddest man I ever knew.”

Stepping out onto the sidewalk, I aimed my camera at the vertical marquee mounted on the second story. Yellow and white light bulbs spelled out “The Liberty Theatre.” As I marveled at the retro signage, a young woman with binoculars and a backpack paused beside me.

“What is this place?” she asked.

“It’s an old vaudeville palace,” I told her with barely contained pride.

“Vaudeville?” she repeated. Her eyebrows drew together in confusion.

“Variety acts,” I explained. “Music, tap dancing, sword-swallowing, trained dogs, trained ducks, contortionists, jugglers …”

“Tell me more,” she said. So I stepped under the green metal dome past the glass-walled box office and pushed open the wooden doors to lead her inside.

In downtown Astoria, Oregon, the historic Liberty Theatre once welcomed the variety acts of vaudeville’s golden age. Photo: Danita Delimont / Jaynes Gallery.

~~

Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington sits resplendent in shirt, tie, and suit jacket at a white baby grand piano on the Liberty Theatre’s stage, fingers thumping out a deft 4:4 beat. Fourteen musicians in tailored suits and bow ties explode into action behind him, playing one of the Duke’s most famous compositions: “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If it Ain’t Got that Swing).”

In the auditorium, hundreds of men, women, and children perch on the edges of their velvet-cushioned seats, bobbing their heads and tapping their toes to the jazzy beat. One by one, the musicians stand for their solos in the spotlight — three singers, sax and trumpet, trombone and upright bass — while Ellington smiles and smiles, keeping time at the white baby grand.

It’s a shocking juxtaposition: the image of an all-Black band enthralling Astorians in a region notorious as a hotbed of racial violence. While Ellington and his musicians took to the Liberty’s stage in the mid-1930s, their civilian counterparts lived under Ku Klux Klan governance in the city and struggled with discrimination from co-workers and business owners. Many remembered how just a decade before, the Klan burned a giant cross on a hill overlooking Astoria, striking fear into the hearts of Black and Mexican and Chinese residents, along with Jews and Catholics as well.

The audience watching Ellington’s band — and indeed any performing group at the Liberty — was overwhelmingly white. Exclusionary laws, though stricken from the state’s constitution in 1926, had discouraged Black people from settling in Oregon. By the 1930s, when the Duke and his orchestra graced the town’s stage, Black residents made up just 2% of the state’s population.

Ellington rented his own train car so he and his musicians would have a safe place to eat and sleep when restaurants denied them service and hotels refused to rent them rooms. But on stage, basking in the golden light spilling from the grand chandelier, the orchestra performed to ripsnorting acclaim by the very people who might otherwise do them harm.

I imagined them pushing toward the building’s ornate wooden doors, laughing and shouting in anticipation of the spectacles within.

“Jazz is the only unhampered, unhindered expression of complete freedom yet produced in this country,” Ellington reportedly said.

Though Ellington isn’t considered a vaudeville act, he and his musicians occasionally hitched their wagon to vaudeville’s welcoming star and found in the art form a sanctuary of sorts from the racist bigotry that complicated the lives of those in the social minority.

Vaudeville was a place where performers, regardless of race and ethnicity, age, social status, religion, gender identity, and sexual preference could make audiences laugh or gasp or cry or dance in their thirty-five-cent seats. Backstage, performers of all demographics mingled behind the heavy red curtains, unified by the business of earning a paycheck while putting on a spectacular show.

However, past the spectacle and the backstage camaraderie lurked an even greater motivation for performers to excel; they learned to trade their fame for a prize much more vital than money.

~~

Florence Hines saunters across the stage in a silk-edged, three-piece suit with a black bowler hat atop her head. She swings a silver-tipped cane, delivering a stream of witty patter. The audience explodes into laughter. She’s spoofing the dandy — a narcissistic 1920s gentleman who preens in his fashionable clothes and prides himself on his ability to hold both his liquor and his ladies.

In the spotlight, Hines smirks at the onlookers in their cushioned seats below. They’ve paid good money to watch her famed drag king routine, and she launches into her best-loved piece: “Hi Waiter, A Dozen More Bottles.”

“I’m a fellow, who’s up on the times,” she croons.

“Just the boy for a lark or a spree.

There’s a chap that’s dead stuck on women and wine,

you can bet your old boots that it’s me.”

The crowd applauds, stamping their feet and smacking each other on the shoulders with hilarity. Hines — a Black lesbian working at the turn of the 20th century — found a special kind of power in making fun of men with “effeminate” traits by becoming one herself.

At a time when LGBTQ+ people were labeled “sexual deviants,” cross-dressing performers and those who identified as queer found not only a home on big city vaudeville stages, but also hefty salaries and admiration from queer and straight audiences alike. One of history’s most famous drag queens, Julian Eltinge, became so beloved that manufacturers paid him to endorse everything from face creams to beauty magazines, corsets to cigars. His performances made him a fortune.

Like Eltinge, Hines embraced vaudeville’s fascination with spectacle. In an all-Black musical called The Creole Show in New York City, her dandy act earned her the highest salary of any Black female performer at the time. A dressing room fist fight with co-star Marie Roberts only added to her appeal. The Cincinnati Enquirer, noting that the women shared “the utmost intimacy,” gave a glowing report of the brawl with the headline “Florence Hines Slugs Marie Roberts in the Most Approved Fashion Behind the Scenes.”

Male and female impersonators captivated audiences around the world. Still, many queer people navigating life outside of theaters and urban locations found themselves harassed and threatened with jail if they acknowledged their sexual identity in public. A man insulted Hines and another female performer while they were running to catch a cable car after a show; he shoved them into a gutter where they sustained minor injuries.

Even Eltinge, who never made his sexuality known, felt compelled to throw homophobes off his expensive scent. A 1920s-era photo shows him posing on a Japanese dock with a beautiful young lady on his arm — a woman he identified for the photographer as his wife, even though no marriage records exist. And though Eltinge lived in a posh California villa with a woman, that woman was his mother.

Female impersonator Julian Eltinge and a woman he identified as his wife stand on the S.S. Siberia at dock in Yokohama-shi, Japan. Eltinge, however, is not known to have married. Photo: National Photo Company Collection / Library of Congress.

Frederic La Delle’s 1913 book How to Enter Vaudeville details dozens of ways in which potential performers could break into show business — from training a duck to quack during key moments of a song like comedian Gus Visser to swallowing different-colored handkerchiefs and regurgitating them in the audience’s requested sequence of hues like Hadji Ali. Whether the performance showcased a highwire or a saxophone, a charming cross-dresser or an “exotic” acrobat, the trick to fame lay not only in the novel, but also in the taboo.

~~

In her 90s, my great-grandmother Mary still flashed the sparkling smile and mirthful blue eyes that had been her trademark during her decades-long career in show business. On breaks from college near her home in Monterey, I traded haircuts and my homemade oatmeal cookies for her stories about running away from her family’s farm to see the lights of Broadway.

She joined the circus as a bareback rider in 1919 and met the man who would become her husband — a comedian and acrobat who went by the name Hap Hazard and performed an act in which he slid down a tightwire on his head. (Before her death at 95, she gave me the helmet he constructed out of leather with a steel groove down the middle for the wire.)

Hap pauses a beat, allowing people to admire his wife’s shapely silk-stockinged ankles.

They married — not for love, but to take their new vaudeville act on the road; in the early 1920s, it was indecent for a man and woman to travel together otherwise. Mary wasn’t a spectacular wire-walker, dancer, or singer. She didn’t juggle or play an instrument. She traded on her looks to perform as Hap’s sidekick, hiding her quick wit and accepting her fame merely as a renowned beauty in exchange for the privilege of traveling the country, and later, the world. When, in the 1930s, cinema replaced vaudeville as the preferred form of entertainment in the U.S., they toured theaters in Europe.

“We crossed the Atlantic nine times,” Mary liked to brag. “We played vaudeville houses all over the U.K. and France, then performed with Bob Hope in the USO.”

As she shared her recollections over prune juice and cookies, she would reach into a cloth bag affixed to her walker, pulling out images from a curated selection of photos that took us back in time.

Mary Hart poses for her headshot created by the famed Daguerre Studio of Chicago. Though the specific photographer is unknown, Emily Gallagher — a daguerreotype photographer who worked for the studio — was said to be a favorite among female performers. Photo: Daguerre Studio of Chicago / Courtesy of Melissa Hart.

~~

Hap Hazard balances in clown makeup on the back rungs of a chair eight feet up on a tight wire, juggling painted wooden clubs in the spotlight. He tosses the clubs down to Mary in a short, red sequined dress. Her black curls shine as she hands up a saxophone. Hap stands on the chair, still balanced on the wire, and plays a few bars of “Saxophobia” — the one song he knows. The audience whoops with delight.

Hap Hazard perfecting his act high up in the air. Photo courtesy of Melissa Hart.

Hap leaps to the ground and launches into a comedy routine with his wife. Long before Eugene Levy played the straight man to Catherine O’Hara’s dippy jokester, Mary feigned earnest innocence to set up Hap’s punchlines.

“Something’s wrong with my hen, Hap,” she says and casts an imploring look into the audience. “The bird keeps pecking my leg.”

Hap pauses a beat, allowing people to admire his wife’s shapely silk-stockinged ankles. Then, he pulls his long face into a mournful expression.

“Why Mary,” he drawls, “your hen’s so mean that she lays deviled eggs.”

This was among the funniest of Hap’s jokes, scribbled into a little notebook I read a century after they were written. My great-grandparents bequeathed me boxes and boxes of their scrapbooks, photos, posters, programs, and newspaper clippings. “Hap Hazard the Careless Comedian and Mary Hart who Cares Less” performed on vaudeville circuits around the world. A single advertisement mentioned their performance at the Liberty.

I stood on the stage where they once stood, gazing out at the lush auditorium with its rows and rows of crimson seats. The magnificent chandelier, stained glass in various shades of yellow and orange, cast a buttery light upon a series of 100-year-old paintings depicting Venetian canal scenes. Architects designed vaudeville theaters to resemble foreign locations; audiences loved feeling as though they’d been transported to Italy or Morocco or Egypt or Iraq for a night.

On stage, basking in the golden light spilling from the grand chandelier, the orchestra performed to ripsnorting acclaim by the very people who might otherwise do them harm.

The young woman with the binoculars followed me into the theater and stood at the back of the auditorium, taking in the artwork and the architecture and the reverential silence of the space. I thought of the spectators that packed these seats three generations ago and how so many of their favorite headliners were performers we’d now describe as “underrepresented.” But oh, how these artists represented. Without them, small town audiences might never have seen acrobats from Mexico, a dance team from Japan, a man in heels and a dress. I like to think these entertainers took a stand against the KKK, brandishing their sequins and their jokes, triumphing in their revelry and compassion for humanity.

~~

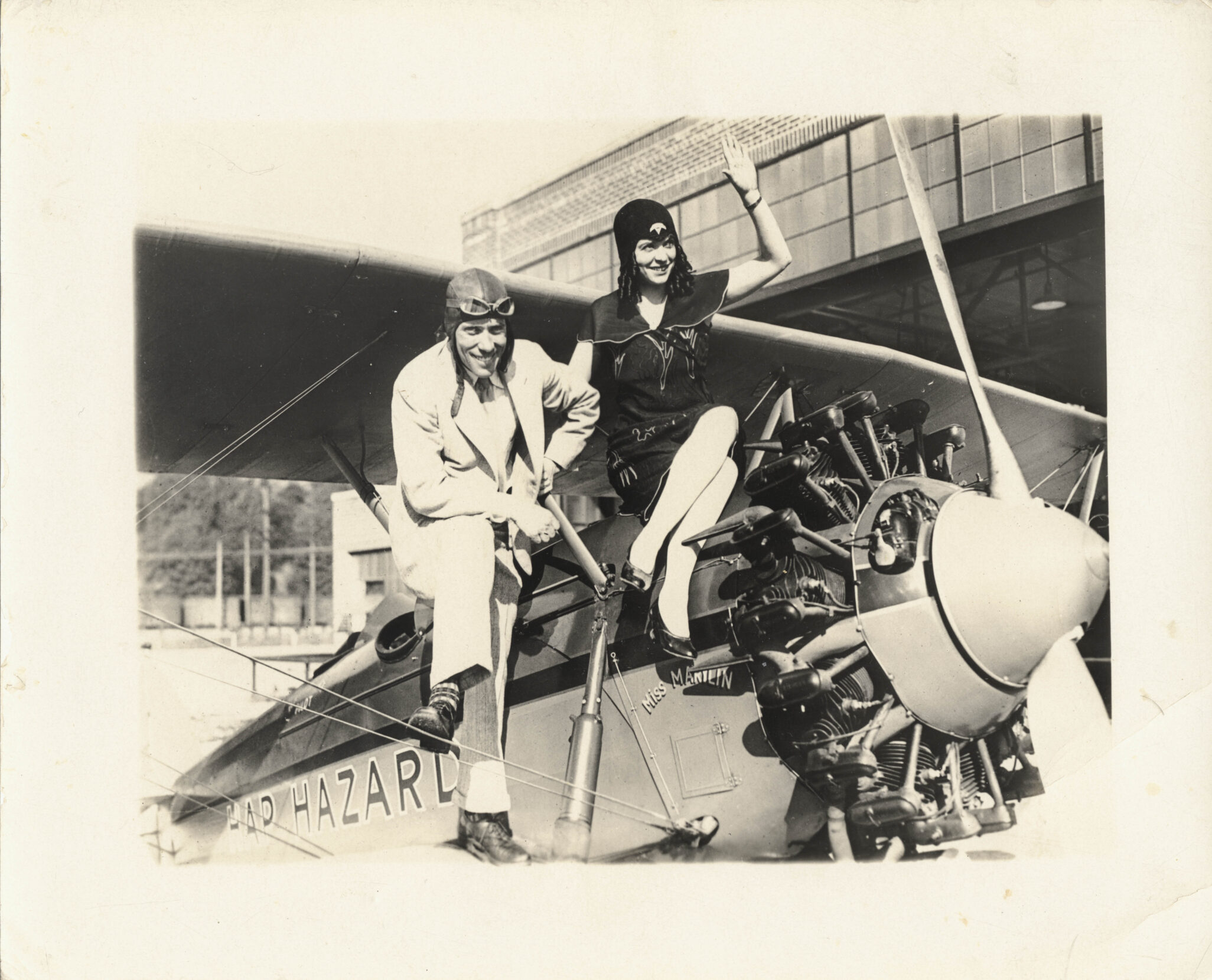

Hap and Mary hailed from St. Helena, California, and Bethany, Missouri, respectively. They were white, straight (as far as I know), and cis-gendered. Faced with a glut of husband-wife comedy teams, they bought a two-seater biplane and made headlines flying from theater to theater — often with my preschool-aged grandmother in tow.

Aviation was still new in the 1920s and 30s, and Hap used it to impress. As he approached each town, he flipped his plane over so those below could read “Hap Hazard” painted on the wings.

Mary Hart and Hap Hazard pose on their plane. Photo courtesy of Melissa Hart.

People flocked to see my comely, daring aerialist great-grandparents up on stage.

Each night after the show, Hap and Mary hosted potlucks in their hotel room which would fill with animal trainers, acrobats, drag kings and queens, and comics who embraced Irish or Italian or Polish or Jewish stereotypes for a laugh.

Hap and Mary traveled on the same circuit as violinist and funny man Ben K. Benny. Born Benjamin Kubelsky, the son of Jewish immigrants, he would become the world-famous comic Jack Benny, whose stage persona portrayed a miser. In one of his most famous bits, he gets mugged.

“Don’t make a move,” the thief growls. “This is a stickup. Now, come on — your money or your life.”

Benny pauses a long moment. The audience howls with laughter. The thief repeats his request.

Finally, Benny replies in an aggrieved tone, “I’m thinking it over!”

Whether he intentionally played up the stereotype of Jewish men as skinflints or simply chose this trait as one of many in his comedy routine, people adored him. Yet he performed at the Liberty Theatre in a state ruled during the 1920s by the KKK, who paraded through the streets in their white robes and hoods, posed with government officials on the front pages of newspapers, boycotted Jewish-owned stores, and — quite possibly — burned down synagogues (though the group denied responsibility for the latter). Did Benny’s act fan flames of anti-Semitism or subvert them?

Standing in the nearly empty theater, I contemplated the murkiness of the question. How could Hines, with her tuxedoed posturing, and Eltinge, with his corset and heels, continue to thrill audiences who — meeting either on the street — might report them to the authorities for indecency or worse? How did these performers reconcile playing into the bigotry against their own marginalized demographics just to make a buck?

My great-grandparents participated for decades in an art form that trafficked in racist and homophobic stereotypes. Were they complicit in perpetuating prejudice? Was my pride in their career naive?

~~

The trick to fame lay not only in the novel, but also in the taboo.

Black performer Bert Williams spins and jigs center stage to the staccato beat of the drummer and trumpet player buzzing behind him. The audience roars, the adrenaline electrifying. Williams wears a ragged evening coat and a goofy straw hat trimmed with pompoms that bounce maniacally as he dances. He speaks with a drawl; he walks with a shuffle. White makeup accentuates the outline of his mouth, stark against the burnt cork darkening the rest of his face.

Bert Williams, the first Black man to headline Broadway’s Ziegfeld Follies and one of the most famous comedians in vaudeville, was forced to perform in blackface.

In vaudeville’s early days, many Black performers claimed to be freed slaves — catnip for voyeuristic attendees in the vaudeville circuit for white audiences. Entertainers shuffled and scraped and bowed; they slurred “Yes, massah” and “No, massah.” But their comedy came at a cost. Fellow performer W.C. Fields called Williams “the funniest man I ever saw — and the saddest man I ever knew.”

Beginning in the late 1800s, legendary vaudevillian Bert Williams and his business partner created and starred in pioneering vaudeville shows and full musical theater productions. Their 1903 production, In Dahomey, was the first all-Black musical comedy to take stage at a major Broadway theater. Photo: Samuel Lumiere / Library of Congress.

But while low wage jobs in the 1920s paid up to $14 a week ($10 if you were a woman), vaudeville performers could make hundreds of dollars a week performing their five-minute act a couple of times a day. For my great-grandparents, it beat the hell out of teaching grammar school (Mary) or scrubbing toilets in the family sanitorium (Hap). For his part, Williams earned an annual salary of $50,000 — the equivalent of $1.5 million dollars today.

~~

After Hap’s 1973 death in his homebuilt plane, Mary and her daughter (my grandmother) moved in together. Every Sunday evening for five years, they pulled their chairs close to the TV and cranked up the volume, the better to hear Kermit the Frog’s plea for decorum among the motley collection of Jim Henson’s puppets in The Muppet Show.

The program, which aired from 1976 to 1981, bears all the hallmarks of vaudeville: the red curtain framing the stage, an eclectic cast warming up in the wings, the hecklers on the sides of the auditorium, and the host tearing out his hair (well, green felt) as he attempts to wrangle his actors and musicians and comedians and operatic chickens into some semblance of an organized production. My great-grandmother recognized the frenetic, almost desperate creativity of her showbiz years.

When I watched reruns of the show, another connection became clear. Puerto Rican actor Rita Moreno tangoed with a mop-haired Muppet wearing a striped shirt and neckerchief below an enormous black mustache to hint at his Latin heritage. In a tight pink rhinestone-studded pantsuit, Sir Elton John sang a duet of “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart” with Miss Piggy in a pink feather boa. The Swedish Chef traded on his inscrutable accent, Rizzo the Rat showed off his Italian street smarts, and Alice Cooper spoofed himself in a performance of “Welcome to My Nightmare” complete with coffin, Dracula cape, and talking skeletons.

How did these performers reconcile playing into the bigotry against their own marginalized demographics just to make a buck?

The Muppet Show displayed that same baffling contradiction as its predecessor — as long as you were willing to skewer yourself and your identity on stage, you were welcomed into the fold with open arms.

~~

Thanks to my great-grandmother’s inability to throw anything out, I have a pretty good idea of whom she and Hap welcomed into their late-night potlucks. Vaudevillians had a habit of trading promotional photos on the circuit: Mary’s boxes of 8-by-11 glossies include signed pictures of the Japanese acrobats who performed under the name “The Seven Uyenos,” as well as a quartet of child trumpet and saxophone players billing themselves “The Frankenberg Kiddie Review” and a couple of handsome young men in tight pants — “Pedro and Luis, Mexican Sensations.”

I wondered how Pedro — a man with whom Mary corresponded until the 1970s — felt about performing for supporters of Mexican repatriation, which forced more than a million people out of the U.S. and into Mexico. Some were Mexican nationals, but historians estimate that 60% of the people driven out of the U.S. were U.S. citizens of Mexican descent.

And what of The Nine Uyenos, who tumbled and cavorted for people who had lobbied for the Immigration Act of 1924, which ended Japanese immigration to the U.S. along with all continental Asian immigration?

Mary saved several autographed photos of Lucio and Simplicio Godino — conjoined twins initially brought from the Philippines as boys and displayed as Coney Island sideshow sensations. After returning to the Philippines where the pair studied music, they journeyed back to the U.S. and became celebrities on the vaudeville circuit. They danced and sang and played trumpet and saxophone. In one photo, they posed back-to-back on roller skates.

Most Filipinos, the only Asian immigrant group legally allowed to come to the U.S. while the Philippines was a U.S. territory, worked on California farms picking fruits and vegetables. The Godino brothers and their manager found a way around this backbreaking labor, as did so many other vaudeville performers who would otherwise be forced into menial jobs. In the midst of World War I, the stock market crash, and the Great Depression, vaudevillians did what they had to do in order to survive.

In one of my great-grandmother’s photos, the Godinos beamed alongside their elegant wives, shaking hands with the legendary boxer Joe Louis. The inscription on this particular photo was cryptic: “To Mary and Hap,” one of them wrote, “A swell pair — may what you think of us is not as bad as it all seems — anything for a laugh.”

The Godino twins and their wives with boxer Joe Louis. This image with its inscription to “Mary and Hap” was among the many photos vaudeville performer Mary Hart held on to. Photo courtesy of Melissa Hart.

~~

Hotel Elliott sits just down the street from the Liberty Theatre; Hap and Mary likely spent the night there when they performed. I wandered through the lobby and peeked into an open room.

There were the ghosts of my great-grandparents propping open their door after the show in the early 1930s, gathering all the jugglers and dog trainers, the dancers and singers and roller skaters and clowns for supper.

Lucio and Simplicio Godino shared sandwiches with their wives in one corner of the room. Duke Ellington, cloth napkin draped over his shirt, cut neatly into a slice of turkey in the headliner’s place of honor — the desk chair. Jack Benny and Florence Hines sat cross-legged on the bed with my great-grandparents eating sandwiches and playing a round of pinochle. Only Bert Williams was missing. With a passion for performance even when he was gravely ill, he contracted pneumonia and collapsed on stage, dead at 46 years old.

~~

Most of the vaudeville palaces still standing boast supernatural claims about past performers and audience members. Ghosts are good for business. They attract tourists and fill locals with a pride that sometimes manifests as funds to repair a shaky Renaissance column or fraying Persian rug. The Liberty claims “Handsome Paul,” a spirit who roams the auditorium and the lobby in a white tuxedo and a Panama hat, slamming doors and turning on the popcorn machine and soda fountain in the middle of the night.

But as I walked up the carpeted stairs into the balcony, I saw more ghosts in this theater: Duke Ellington and his musicians, Jack Benny when he was still Ben K., a long-faced man in clown makeup with his beautiful assistant in a sequined gown.

“May what you think of us is not as bad as it all seems — anything for a laugh.”

In the end, I think vaudeville — like much of our contemporary comedy — was both incredibly bigoted and incredibly inclusive. These days, drag queens make millions poking fun at each other’s false eyelashes and wigs and wardrobe malfunctions while actors and comedians perform parodies of marginalized groups the world over — just as these very groups face bigotry and violence. Satire, parody, and self-deprecation have transfixed us over centuries.

My great-grandparents participated in an art form that dealt in dangerous stereotypes, but they were also allies in a community that represented diversity under duress.

Ultimately, the spotlight of vaudeville shone beyond the stage. Turned on the audience, it illuminated people’s prejudices even as they chortled with delight.

~~

I left the ghosts on stage and stepped out of the lobby and into the bright coastal daylight. My hand lingered on the handle of the heavy wooden door; my great-grandparents surely touched this same surface a hundred years before.

The young woman with the backpack and binoculars walked out of the lobby and joined me under the green metal awning beside the glass-walled box office.

“My great-grandparents performed here a century ago,” I told her. “They were vaudevillians.”

She looked at me with new respect. “That’s amazing,” she said.

“Yes,” I replied. “They were.”

The author’s great grandfather Hap Hazard juggles atop a precariously balanced chair, while her great grandmother Mary Hart looks up at her husband and vaudeville partner. Photo courtesy of Melissa Hart.

Melissa Hart

When not peering through her magnifying glass at slime molds, Melissa Hart writes both fiction and non-fiction with a particular interest in history and Pacific Northwest nature.